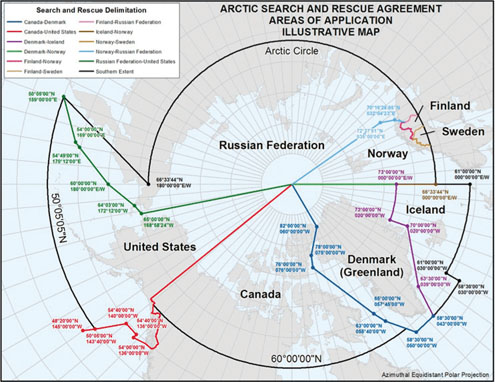

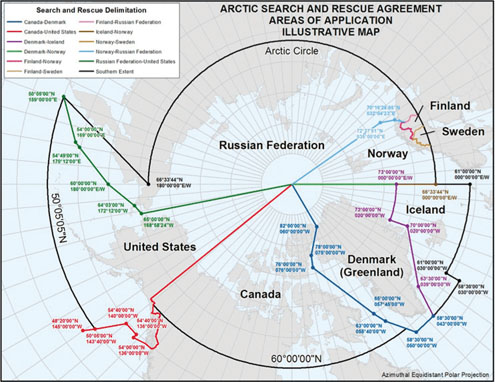

Figure 1. SAR regions relevant to the Arctic SAR Agreement and the Barents SAR Agreement47

Are Kristoffer Sydnes*

Department of Engineering Science and Safety, Faculty of Science and Technology, UiT – The Arctic University of Norway, Tromsø, Norway

Maria Sydnes

Department of Engineering Science and Safety, Faculty of Science and Technology, UiT – The Arctic University of Norway, Tromsø, Norway

Yngve Antonsen

Norut Northern Research Institute, Tromsø, Norway

Abstract

SAR in the Arctic is a complex and dynamic cross-disciplinary activity that requires the combined effort of multiple actors with specialized human and technical resources. Due to limited resources and infrastructure in the Arctic, international cooperation is particularly important. This article applies a conceptual framework drawn from regime-theory to study SAR cooperation in the Arctic. More specifically, we apply the three dimensions of regime effectiveness (outputs, outcomes and impacts) to examine the regimes established by the 2011 Arctic SAR Agreement and the 1995 Barents SAR Agreement. The study addresses the rights and duties established by the regimes and their institutional arrangements for cooperation. Further, it investigates the importance of operational cooperation among response agencies in understanding the development and effectiveness of the regimes. The study concludes that the Arctic SAR regime is still under implementation. The agreement has entered into force but a series of steps needs to be taken for the common SAR system to be operative. Consequently, the regime is in the early stages of development and any evaluations of its impact are premature. The parties have implemented the Barents SAR regime both formally and in practice. Though the regime is generally held to have a positive effect on cooperation between the parties, there is a range of challenges that raise questions regarding its capacity to provide for a coordinated and effective joint SAR operation. The study further concludes that treating regime effectiveness in terms of a causal link between output, outcome and impact should be done with caution. It also argues that the focus of regime theory on interest-based decision-making among regime parties should be supplemented by investigating the operative and informal aspects of cooperation.

Keywords: search and rescue; international cooperation; Norwegian–Russian cooperation; Arctic Council; Barents Sea; Arctic

Responsible Editor: Øyvind Ravna, UiT – The Arctic University of Norway, Tromsø, Norway.

Received: March 2017; Accepted: June 2017; Published: September 2017

*Correspondence to: Are Kristoffer Sydnes, Dep. of Engineering Science and Safety, Faculty of Science and Technology, UiT – The Arctic University of Norway, Tromsø, Norway. Email: are.sydnes@uit.no

©2017 A.K. Sydnes et al. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), allowing third parties to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format and to remix, transform, and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercially, provided the original work is properly cited and states its license.

Citation: A.K. Sydnes et al. “International Cooperation on Search and Rescue in the Arctic.” Arctic Review on Law and Politics, Vol. 8, 2017, pp. 109–136. http://dx.doi.org/10.23865/arctic.v8.705

The need for better search and rescue (SAR) infrastructure and capabilities in the Arctic is now widely recognized.1 The Arctic is characterized by vast distances, a harsh climate, limited infrastructure, communication challenges, and sparse population,2 with economic activities traditionally focused on harvesting living marine resources. Due to climate change, new natural resources have become available for utilization, and new Arctic regions are opening for commercial activities – including large-scale plans for petroleum development in the Euro-Arctic regions of Norway3 and Russia.4 There has also been an increase in maritime traffic related to the petroleum industry, cruise tourism, and the opening of the Northern Sea Route.5 All this brings a greater need for inter-Arctic cooperation.6

SAR involves a wide range of technical and human resources, provided by civilian and public actors, and military agencies. It includes vessels, SAR helicopters, airplanes and satellite imagery coordinated through various communication platforms. However, resources for SAR operations in the Arctic are limited, in terms of capacity and the range of current technology.7 Acknowledging that international cooperation is a prerequisite for effective SAR in the Arctic, the Arctic states have taken initiatives to collectively strengthen SAR infrastructure.

This article focuses on cooperation on aeronautical and maritime SAR in the Arctic, in particular the Barents region.8 It offers an overview of international law and agreements pertaining to SAR in the Arctic, and examines two SAR agreements of special importance to the Arctic: the Arctic SAR Agreement adopted by the members of the Arctic Council in 2011;9 and the 1995 Barents SAR Agreement between the Russian government and the Norwegian government on cooperation in search and rescue in the Barents Sea.10

Previous studies of international SAR in the Arctic have largely focused on the substantive parts of international agreements, that is, what rights and duties are establish for the parties.11 Some have addressed how these agreements may influence the geopolitical interests of States in the Arctic.12 There are also efforts to map the availability and capacity of technical and human SAR resources in the Arctic.13 However, so far, there has been limited attention paid to the operative cooperation established by SAR regimes, in terms of establishing a joint emergency response capacity. There are no academic publications on the Barents SAR regime known to the authors. This reflects the limited information available on international SAR cooperation in the Barents Sea. For the Arctic SAR regime, there have been initial efforts to study its legal and political implications. In both regards, this study provides an initial effort to investigate the implementation and effectiveness of SAR cooperation.

We begin with the substantive rights and duties established regarding SAR in the Arctic region, asking: what obligations do the agreements establish in terms of the duty to assist, the level of preparedness required, border-crossing, and other matters of a substantive nature? We then turn to the operative component – the institutional arrangements established by the two regimes to facilitate cooperation and coordination between the parties, through institutionalized decision-making bodies, working-groups, contingency plans, programs, exercises, in addition to more informal modes of cooperation.14 Such arrangements may prove crucial to ensuring effective cooperation and regime development. Thirdly, drawing on reports of exercises and interviews with SAR professionals, we ask whether there are specific challenges related to the two agreements that influence effective SAR cooperation. Given the scope of this study and limited data availability, we cannot provide a comprehensive study of regime effectiveness.15 Since there have been no joint SAR operations, we focus on identifying challenges. However, SAR is about the ability of the parties to provide mutual assistance and to conduct joint operations. This ability is not merely dependent on political decisions, but relies on the ability of professional responders with highly specialized functions to coordinate their actions in an effective manner. The paper argues that when studying regimes whose purpose is to provide for joint operations, there is a need to move beyond the logic of political interests, as reflected in the negotiated agreements. Both in terms of regime development and effectiveness, the operational aspects of the regime (its capacity for joint action) need to be considered.

After presenting the methods and data of this study, we offer an overview of the existing international regulatory framework established for SAR in the Arctic. Empirical sections which focus on the Arctic SAR Agreement and Barents SAR Agreement follow. We conclude with a discussion of challenges regarding the performance of the two agreements.

Both the Arctic and Barents SAR Agreements can be regarded as establishing international regimes, i.e. ‘social institutions consisting of agreed upon principles, norms, rules, procedures and programs that govern the interaction of actors in a specific issue area.’16 Regimes consist of a substantive component (principles, norms, rules) to direct the cooperation of the parties, and an operative component (procedures and programs) to direct practical and ongoing cooperation among the parties.17 This article deals with both components of the Arctic and Barents SAR Agreements.

There is a general focus in regime theory on how cooperation is both based on and influences the political interests of the parties.18 Following this approach, effectiveness becomes a matter of achieving common interests through cooperation based on the regime in question. It is often assumed, implicitly or explicitly, that political interest is the determining driving force in the cooperation of the parties and the evolution of the regime. This commonly takes place through established decision-making bodies established by the regime. More recently, focus has also turned to the role of epistemic communities and/or professions as driving forces in regime development and effectiveness.19 This type of cooperation is often at the operational level of the regime. It may also play an important role in determining both the development and effectiveness of international regimes, in particular when considering regimes such as SAR, where the aim is to establish joint operations.

This implies moving from the merely formal outputs of cooperation, and discussing the effectiveness of a regime’s output, outcome and impact. What we want to observe in this case are the coordinated efforts of parties to provide for effective SAR within the mandate area.

Establishing reliable indicators for regime effectiveness is a challenge.20 In this particular case, there are no objective standards for evaluation. Our assessments are therefore based on qualitative data from evaluation reports from training exercises and interview data. The effectiveness of the regimes will be discussed based on their outputs, outcomes, and impacts.21 Outputs reflects the rules and regulations established by the constituting agreements, in addition to the formal measures taken to move them from paper to practice, both internationally and domestically.22 In general, it is conceived that regime effectiveness may be dependent on the requirements established by the rules regulating the parties.23 Outcomes denotes behavioral changes caused by the implementation of the regime,24 including the parties’ compliance to the regime.25 Impacts refers to the problem-solving capacity of a regime26 or the ability to achieve its purpose.27 For a full picture of regime effectiveness, one would wish to include all indicators of regime effectiveness. However, moving from one indicator of regime effectiveness to the next is not without challenges:

‘… studying outputs is usually a necessary starting point, but this needs to be supplemented with studies of outcomes to enable a better grasp on what is happening in practice. Impact indicators are so demanding in terms of methodology that they are difficult to apply in empirical studies’.28

Nevertheless, these indicators provide a useful analytical framework for discussing the development and effectiveness of the cases in this study.

The study builds largely on document studies: international conventions; the two above-mentioned Agreements; reports from the parties to the agreements; presentations and reports from the Arctic Council Emergency Prevention, Preparedness and Response (EPPR) Working Group and Senior Arctic Officials Meetings; training exercise evaluation reports; and secondary literature where available. These provide a basis for examining the procedures and practices established by the Agreements, developments under the Agreements, and challenges highlighted in exercise evaluation reports.

In addition, a series of anonymized, semi-structured interviews was conducted.29 As publicly available data regarding SAR in the Arctic and the Barents region are limited, these interviews aimed at shedding light on the parties’ experiences, exploring factors that facilitate or inhibit cooperation/coordination on SAR. Questions were both fact-oriented and directed at the responders’ individual experiences and attitudes. Nine interviews were conducted with Norwegian and Russian representatives of organizations relevant to national and international SAR in the Arctic. Gathering interview-data regarding Russian SAR proved difficult, so our study relies on one Russian informant with a central role in the Murmansk Marine Rescue Coordination Centre (MRCC). Interviews were conducted in Bodø and Murmansk in 2015. Three interviews were recorded, with informants’ consent; notes were taken in the remaining cases. The interviews lasted from 30 minutes to two hours. Two authors participated during four interviews; in the other cases, a single author conducted the interviews. The recorded interviews were later transcribed. All interview notes were analyzed and discussed by the three authors. The transcribed interviews were analyzed by the authors employing directed qualitative content analysis.30 Interview data were categorized into four main themes: rights and duties established in accordance with the Agreements; cooperation and coordination platforms; experiences and challenges; and facilitators and inhibitors. All informants are number-coded (see Table 1) and referred to by number in the text. The interviews were conducted in English, Norwegian and Russian. Parts of the transcribed interviews were subsequently translated into English. All quotes from interviews are the authors’ translations.

In discussing experiences from cooperation, we rely predominantly on document analysis of the Arctic SAR Agreement. The main source of data on experiences related to the Barents SAR Agreement were interviews originally conducted under the framework of the SARINOR project.31 In examining experiences from the bilateral Norwegian–Russian cooperation on SAR, we rely heavily on the views expressed by representatives from the JRCC and the MRCC. These are the key agencies responsible for implementation of the Barents SAR Agreement; the other organizations participate in bilateral cooperation mainly through exercises.

While our data make it possible to discuss developments and identify challenges for cooperation, they cannot provide a basis for a comprehensive study of regime effectiveness.

Several widely recognized international agreements establish the legal international frameworks for SAR. These legal instruments articulate the international standards and rules on SAR within which the Arctic and Barents SAR regimes are nested, and stipulate the rights and duties of the parties relating to SAR as well as steps to be followed in SAR operations.32

The 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (LOS Convention) established the basic legal framework for managing all maritime activities including the Arctic. The LOS Convention establishes the rights and duties of states regarding zones of jurisdiction, rights to natural resources, and navigation. Notably, it also requires coastal states to promote, through regional cooperation if necessary, “the establishment, operation and maintenance of an adequate and effective search and rescue service regarding safety on and over the sea.”33

The 1974 International Convention for the Safety of life at Sea (SOLAS, 1974), with multiple amendments, is generally regarded as the key international treaty concerning merchant ship safety.34 The Convention provides a framework of rules, codes, and procedures regarding the international safety standards for the construction, machinery, equipment, and operation of ships. In particular, Chapter 5 of the Convention obliges the masters of a ship at sea “to proceed with all speed to the assistance of persons in distress.”35

The 1979 International Convention on Maritime Search and Rescue (the SAR Convention, 1979) establishes the international system covering search and rescue operations.36 The Convention requires that the parties ensure that arrangements are made for the provision of adequate SAR services in their coastal waters, including the establishment of rescue co-ordination centers and sub-centers.37 It encourages the parties to enter into SAR agreements with neighboring states, provide necessary assistance, and facilitate coordination during search and rescue operations.38 It further outlines operating procedures to be followed in the event of emergencies or alerts and during SAR operations.39 To facilitate search and rescue operations, the parties are required to establish ship-reporting systems, under which ships report their position to a coastal radio station.40 Following the 1979 SAR Convention, the International Maritime Organization’s Maritime Safety Committee divided the world’s oceans into 13 SAR areas, in each of which the countries concerned have delimited search and rescue regions for which they are responsible (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. SAR regions relevant to the Arctic SAR Agreement and the Barents SAR Agreement47

The 1944 Convention on International Civil Aviation (the Chicago Convention, 1944) established the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) in 1947, a UN specialized agency charged with coordinating and regulating international air travel. The Convention establishes the rights of signatory states over their territorial airspace, aircraft registration and safety, and lays down basic principles relating to international transport of dangerous goods by air.41 The International Aeronautical and Maritime Search and Rescue Manual (IAMSAR Manual), developed jointly by the International Maritime Organization (IMO) and the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO), provides guidelines for a common aviation and maritime approach to organizing and providing search and rescue services. The manual has three volumes: on the establishment and improvement of national and regional SAR systems and international cooperation (Volume I), guidelines for those who plan and coordinate SAR operations and exercises (Volume II) and guidelines for the conduct of operations on-scene (Volume III).42

However, the general IMO safety conventions have limitations regarding Arctic shipping.43 Therefore, the IMO adopted the International Code for Ships Operating in Polar Waters (the Polar Code) and related amendments to the SOLAS Convention in November 2014. The Polar Code deals with the full range of design, construction, equipment, operational, training, SAR and environmental protection matters relevant to ships operating in the inhospitable waters surrounding the poles.44 Every ship to which the Polar Code applies shall have a Polar Ship Certificate, issued by the flag state.45 In addition, every ship shall carry a Polar Water Operational Manual including risk-based procedures for SAR.46

To specify the existing international framework on SAR activities to local conditions States enter regional agreements of a more specific nature. In the following, this study has a focus on the 2011 Arctic SAR Agreement and the 1995 Barents SAR Agreements.

At its 2009 Ministerial Meeting in Tromsø, the Arctic Council decided to establish a Task Force mandated with developing an international instrument for SAR cooperation in the Arctic. This resulted in the production of the Agreement on Cooperation in Aeronautical and Maritime Search and Rescue in the Arctic (the Arctic SAR Agreement). The Agreement was signed by the eight Arctic states48 at the Nuuk Ministerial meeting in 201149 and entered into force in January 2013.50 The Arctic SAR Agreement is the first legally binding instrument negotiated under the auspices of the Arctic Council.51 However, it should be noted that several Arctic bi- and multilateral agreements covering various geographical areas and activities existed prior to 2011.52 The Arctic SAR Agreement builds on this pre-existing cooperation,53 and provides a comprehensive pan-Arctic SAR framework.

The Agreement contains 20 Articles, one Annex and three Appendixes that establish a regional mechanism for international cooperation on SAR in the Arctic. The Appendixes provide an overview (APPENDIX I - Competent Authorities, APPENDIX II - Search and Rescue Agencies, APPENDIX III - Rescue Coordination Centers) of the specific authorities of each party responsible for different aspects of SAR operations and related activities. These Appendixes are of an informative nature and parties can unilaterally alter the information in the appendixes as long as they inform the other parties.54 The Appendixes correspond to the three layers of the SAR decision-making hierarchy where “competent authorities” represent the political level, “agencies” are government units with a specific functional and/or territorial competence, and “rescue coordination centers” are the units which have overall operational responsibility during SAR operations.55 Providing a clear hierarchy and an overview of the specific national agencies responsible for SAR is important particularly due to the large number of national ministries, agencies and other units participating in SAR activities. The aim is to streamline communication, which is commonly regarded an ongoing challenge during SAR operations. The objective of the Agreement is to further “strengthen aeronautical and maritime search and rescue cooperation and coordination in the Arctic” (Art. 2). The geographical scope is specified in the Annex. Each member-state is responsible for a particular SAR area, in accordance with the 1979 SAR Convention (see Figure 1). These areas are “not related to and shall not prejudice the delimitation of any boundary between States or their sovereignty, sovereign rights or jurisdiction.”56 Within their areas, the members are to ‘promote the establishment, operation and maintenance of an adequate and effective’ SAR capability.57 Further, each party commits to nominating specific national authorities that will have full discretion in the field of SAR in its area. These national authorities are required not only to take efficient measures, but also to notify other relevant national authorities when appropriate. The competent authorities of the parties, agencies responsible for search and rescue, and rescue coordination centers are outlined in Articles 4 through 6 and specified in the Appendixes.

The Arctic SAR Agreement was concluded in accordance with the 1979 SAR Convention and the 1944 Chicago Convention,58 which “shall be used as the basis for conducting search and rescue operations under this Agreement.”59 The IAMSAR Manual provides additional guidelines on implementing the Arctic SAR Agreement.60 These three sources establish the basic framework and provide explicit procedures for conducting SAR operations. Without prejudice to the provisions of the SAR and Chicago Conventions, Article 7 of the Arctic SAR Agreement lays down provisions for the conduct of aeronautical and maritime SAR operations; provides that “parties shall ensure that assistance be provided to any person in distress,” and also specifies the procedures for forwarding information and the request for assistance. Importantly, parties that have been requested to provide assistance shall promptly determine whether they are capable of providing assistance, and on which terms.61 The Agreement does not specify the resources that parties are obliged to provide: “[i]mplementation of this Agreement shall be subject to the availability of relevant resources,”62 and all costs related to it are to be paid by the individual parties.63 Thus, it is up to the individual state to decide on the appropriate level of resources designated to SAR under the Agreement. Further, the Agreement specifies that SAR operations shall not prejudice the sovereignty of the coastal state(s).64 The parties must “request permission to enter the territory of a Party or Parties for search and rescue purposes.”65 Importantly, the party receiving a request for entry into its territory shall apply “the most expeditious border crossing procedure possible.”66

Article 9 of the Agreement lays down provisions for the development of cooperation among the parties, stipulating that the parties “shall enhance cooperation among themselves in matters relevant to this Agreement” (para 1). This includes information exchange “to improve the effectiveness of search and rescue operations” (para 2) Such information may concern communication details, information about SAR facilities, overview of available airfields and ports together with their refueling and resupply capabilities, information on fueling, supply and medical facilities and information important for training SAR personnel (para 2). The Agreement offers a comprehensive overview of possible collaborative efforts to facilitate mutual SAR cooperation. These include: exchange of experience; sharing information on meteorological and oceanographic observations; exchange of SAR personnel; arranging joint exercises and training; using ship reporting systems for SAR purposes; sharing information systems, SAR procedures, techniques, equipment and facilities; providing service support of SAR operations; sharing national positions on SAR issues; supporting and implementing joint research and development initiatives; and conducting regular communications checks and exercises (para 3).

In addition to information exchange and the promotion of general collaborative efforts, the Agreement directs the parties to conduct meetings on a regular basis “to consider and resolve issues regarding practical cooperation.”67 The purpose of these meetings is to address issues related to reciprocal visits by SAR experts and their participation in the parties’ national SAR exercise as observers, conducting joint exercises and training. The meetings should also address the development of cooperation under the Agreement; the planning, development, and use of communication systems; review and improvement of international guidelines on SAR in the Arctic; and review of relevant guidance on Arctic meteorological services.68 Further, the parties are encouraged to “conduct a joint review of the operation led by the Party that coordinated the operation.”69

Any amendment to the Agreement is to be undertaken by written agreement of all the parties.70 However, any two parties with adjacent SAR regions may, by mutual agreement, amend information on the delimitation of SAR regions relevant to the Agreement contained in paragraph 1 of the Annex to the Agreement setting forth the delimitation between those regions.71 Further, individual Parties may amend information related to the areas of application of the Agreement specified by paragraph 2 of the Annex to the Agreement, provided that this does not affect the area of any other Party.72 The Agreement offers direct negotiations as a means of settling all disputes between the parties related to the Agreement.73 Any party may at any time withdraw from the Agreement, following written notification to the depository through diplomatic channels at least six months in advance of the effective date of its withdrawal.74

Emergency Preparedness, Prevention and Response (EPPR) is one of the Arctic Council’s six Working Groups. Its main task is to facilitate international cooperation on issues related to the prevention, preparedness and response to all kinds of environmental emergencies in the Arctic. The working group meets twice annually, and has a two-year rotating Chairmanship and a secretariat. It focuses on collecting sufficient and reliable data to underpin scientific recommendations that aid the member-states in establishing national-level procedures.75 Since 2015, SAR issues have been part of the EPPR working mandate. This includes the planning, execution and reporting of SAR activities with follow-up on the Arctic SAR Agreement and addressing relevant findings from SAR exercises.76

The EPPR does not have an operational mandate for SAR (i.e., for participating in actual SAR operations), as that is the responsibility of the member-states. However, the EPPR offers recommendations and information within the Arctic Council and to others and advises the Senior Arctic Officials on relevant SAR incidents and events.77 It supports the Arctic SAR Agreement by addressing relevant lessons learned from SAR exercises and real incidents, and by maintaining a repository of lessons learned and best practices of Arctic SAR incidents and events.78 The EPPR functions as a coordinating body on SAR issues within the Arctic Council, and is to facilitate the implementation of the Arctic SAR Agreement by “focusing on enhancing cooperation, highlighting best practices, exchanging information, analyzing results of exercises, and sharing lessons learned.”79

The establishment of the EPPR Search and Rescue Expert Group (SAR EG) in 201580 is one recent development under the EPPR. This expert group has a strategic focus; its main task is to follow up the implementation of paras. 9 and 10 of the Arctic SAR Agreement on Cooperation and Meetings of the Parties.81 The group held its first meeting during the EPPR Working Group meeting, June 13–15, 2016, in Montreal, Canada.82 The mandate of the group was finalized and approved by the EPPR in December 2016 during the working group meeting in Copenhagen.83 The SAR EG has no operational mandate and reports to the EPPR as a guiding body.84 The expert group is a facilitator whose duty is to support existing fora that deal with Arctic SAR issues “by leveraging high level engagement from government and scientific institutions”.85 Its specific goal is “to identify key lessons of Arctic incidents and exercises and communicate/disseminate effective practices and necessary mitigation or remedial actions to the ministerial level, Member States and other relevant international bodies”.86

The EPPR is also to develop collaboration with the newly established International Arctic Coast Guard Forum (ACGF). In 2015, the eight Arctic nations signed a joint statement establishing ACGF as “an operationally focused, consensus-based organization that leverages collective resources to foster safe, secure, and environmentally responsible maritime activity in the Arctic.”87 The Forum will support the work of the EPPR Working Group by providing an additional platform for cooperation on operational issues, including search and rescue.88 However, the mandate of the ACGF in relation to the 2013 MOSPA Agreement89 and the Arctic SAR Agreement is unclear; the EPPR is working to clarify this, inter alia to avoid overlaps.90

The main source of data for evaluating the Arctic SAR Agreement since its establishment in 2011 are reports from joint exercises. A series of tabletop and live full-scale exercises has been conducted under the Arctic SAR Agreement to date.91 Here we focus on the main findings of the available evaluation reports.

The first exercise organized in accordance with the Arctic SAR Agreement was a tabletop one, held in Whitehorse, Yukon, Canada in 2011. The exercise focused on strategic and operational aspects of aeronautical and maritime SAR in the Arctic and provided the first opportunity to discuss the implementation of the Arctic SAR Agreement.92 The parties exchanged information on national SAR capabilities; discussions examined Arctic SAR scenarios that would require international cooperation and resources.93

The Danish Defense hosted SAREX Greenland Sea 2012, the first full-scale live SAR exercise under the Arctic SAR Agreement. It was held off the east coast of Greenland, and involved a disaster scenario with a medium-sized (160 passengers and crew) cruise ship, including an open sea search operation (simulating a mass rescue operation on a cruise ship) and an in-fjord rescue and evacuation operation.94 The aim was to involve the “Arctic Nations’ SAR organizations and associated authorities and their capabilities in a live exercise … in a remote Arctic environment,” testing communications, equipment and procedures nationally and between the participating nations.95 Fundamentally, the exercise revealed that the Arctic SAR regime as an emergency response system needed to improve its procedures for cooperation and communication and establish a common understanding on how to apply them. The evaluation report identified several more specific challenges, and provided a series of detailed recommendations for the search and rescue phases of SAR operations. In focus here were the lack of adequate planning for evacuation operations, a lack of personnel, coordination problems among emergency medical units, and malfunctions of crisis communication at various levels.96 SAREX 2012 was valuable in identifying gaps in the operative SAR system – while also showing that the challenges were numerous.

SAREX 2013 was conducted on the initiative of Denmark/Greenland to address the challenges identified by SAREX Greenland Sea 2012.97 Due to the short planning cycle, a modified version of SAREX 2012 was used as a scenario. The results of the exercise were generally considered positive. Nevertheless, the evaluation report offers various recommendations on search operations (including means and methods of communication, use of a common log system, search for life rafts from ships, and strengthening the manning of the Joint Arctic Command) and rescue operations (including communication, criminal investigation, rescue teams and safety).98

In October 2015, the Arctic Zephyr 2015 tabletop exercise was held, hosted by the US authorities.99 The scenario was a mass rescue operation to test coordination and command and control among the Arctic nations’ mission partners and relevant stakeholders at various levels.100 Several observations and recommendations were made regarding cooperation and coordination under the Agreement.101 Areas of primary concern included communications, situational awareness, resources, logistical support, strategic messaging and media, and coordination and planning.102 Importantly, the exercise called into question the effectiveness of the regime established by the Arctic SAR Agreement as such. Specifically, the exercise evaluation report underlined that the Agreement does not provide an effective process or mechanism for achieving Article 9 on Cooperation among the Parties and Article 10, Meetings of the Parties. In addition, recognized or codified methods for the coordination of operational SAR activities were lacking, as were standardized processes for sharing lessons learned. The report emphasized that the mere signing of the Arctic SAR Agreement cannot ensure effective cooperation and coordination among the Parties. These must be strengthened by institutionalizing processes through the EPPR Working Group, conducting adequate exercises, and involving relevant participants, including industry.103

Building on the Arctic Zephyr tabletop exercise series, Arctic Chinook was held in Kotzebue, Alaska, August 22–25, 2016. This exercise was hosted by the USA and organized by the US Coast Guard and the US Northern Command. The scenario involved a mass maritime rescue operation in the Arctic from an adventure-class cruise ship that experienced an incident which developed into a catastrophic event.104 A large full-scale SAR exercise is planned for February/March 2019. The exercise will be coordinated by the Finnish Border Guard. As a rehearsal for this exercise, a SAR module will be included in the full scale oil recovery exercise conducted under the 2013 Agreement on Cooperation on Marine Oil Pollution Preparedness and Response in the Arctic (the MOSPA Agreement) scheduled to take place in Finland in February 2018.105

In summary, the Arctic SAR Agreement is a legally binding pan-Arctic agreement that aims to build on the existing international framework and established regional SAR agreements. Its member-states are to promote the establishment of national SAR capabilities within their national SAR areas. The Agreement has established procedures for requesting SAR assistance, border-crossings, and information sharing between the parties, among other things. Since 2011, the EPPR has, first informally and later as part of its mandate, facilitated member-state cooperation. Since 2015 this cooperation has also been facilitated through a SAR Expert Group. Operative collaboration of the parties is developing gradually on the basis of a series of joint exercises, which have also uncovered a range of challenges that must be addressed if the regime is to provide for efficient joint SAR operations.

Norway and Russia have collaborated on SAR at sea since 1956. In 1988, the 1956 agreement on search and rescue at sea between Norway and the Soviet Union was replaced by a more comprehensive agreement.106 The latter was, in turn, replaced by the existing bilateral Barents SAR Agreement of 1995 between Norway and Russia. This Agreement bases its framework for activity on the 1979 International Convention on Maritime Search and Rescue (the SAR Convention, 1979), to which both Norway and Russia are parties. The Barents SAR Agreement does not influence the rights and duties of the parties according to other bi- or multilateral agreements. The IAMSAR manual provides guidelines for operative implementation of the Agreement.

The Barents SAR Agreement contains 12 Articles and an Appendix that clarifies communication channels and procedures. The main norm is that the parties shall provide assistance in search and rescue in the Barents Sea.107 The Agreement sets the conditions for joint operations, the provision of assistance, and clarifies how requests for assistance are to be forwarded:

The SAR services of the Party that receives a message that someone is missing or in distress in the Barents Sea, shall instantly take those measures considered most appropriate to organize and initiate a SAR operation. The Party’s SAR services that receive such a message may, to ensure that necessary assistance is provided as quickly as possible, instantly contact the other Party’s SAR services so that the planning, coordination and conduct of the SAR operation shall be done in consultation between them. The Party’s SAR services that have initiated a SAR operation, can request the other Party’s SAR services for assistance if it considers it necessary for the operation to be conducted.108

Further, the SAR services of two parties are to provide mutual assistance to the extent they have the appropriate resources to do so.109

Article 2 of the Agreement specifies the competent national authorities responsible for the organization and coordination of activities to search for missing persons and rescue people suffering distress in the Barents Sea, and the tasks of these authorities: the Marine Rescue Coordination Center (MRCC) in Murmansk, Russia and the Joint Rescue Coordination Center (JRCC) North Norway. Its Article 5 clarifies how requests on border crossing related to SAR operations are to be forwarded: Requests for rescue units to enter the territorial waters and airspace should be directed to the responsible rescue services of the other party. All necessary information should be provided by the party entering the other’s jurisdiction. The request for entry should be handled as quickly as the situation requires; once granted, information is to be provided regarding the rules and conditions that apply. Rescue units entering the territorial waters or airspace of the other party are to establish communications with the latter’s rescue coordination center and follow its requests.

The Agreement obliges the parties to provide and share information that is of considerable importance for the fulfillment of the Agreement (Art. 7). It clarifies the means and channels of communication with reference to international standards and establishes English as the language of communication (Art.8; Appendix). The Parties agree to inform each other promptly, and further assist in obtaining necessary information on vessels or aircrafts belonging to the other Party that are missing or in distress (Art. 6).

The Agreement does not establish any organizational body, but it encourages the parties to conduct joint meetings when needed to “discuss or facilitate practical measures relating to cooperation in the search of missing persons and rescue of people in distress in the Barents Sea” and joint training exercises.110 In accordance with the Agreement, an annual joint Exercise Barents is to be conducted between Norway and Russia. From 2006, Exercise Barents has covered exercises under both the Barents SAR Agreement and the 1994 Norwegian–Russian Oil Spill Response regime.111 The main objective of Exercise Barents is to “exercise the cooperation between MRCC Murmansk and JRCC North Norway related to SAR and rescue units on scene.”112 In connection with Exercise Barents, two meetings are conducted between Norway and Russia each year. One is to evaluate the previous year’s exercise and plan for the current year. The second is a pre-exercise meeting held two days ahead of the annual exercise to focus on communication, cooperation, safety on scene, and confirmation of earlier agreed-upon resources and objectives for the exercise.113

Joint Norwegian–Russian SAR cooperation has developed over the years, largely through the meetings of the parties in relation to the joint exercises under the Agreement. Even though “progress in this cooperation has been slow, every step … has taken a lot of time and a lot of preparation and discussions ….”,114 most of our informants agree that cooperation has gradually developed and improved over the course of time.115 A representative from JRCC gave the following explanation:

It’s a different kind of cooperation with Russia than with the others. Not that it is problematic, but progress has been slow. We had issues with language, bureaucracy and stuff, but I think the reason why we still keep at it is that we see progress. … [I]f you go back 10 or 15 years, people were asking - Is it really worth putting so much effort and money into this cooperation and these exercises? Do they really result in anything valuable?” And the answer from us was: “Yes, it is important”. … It varies a bit from year to year. Sometimes there were people … who were not so interested when we met with them for the planning …. But our main partner, MRCC [Murmansk Rescue Coordination Center], has always been positive to this cooperation.116

At the informal level, there seems to have developed a degree of trust between participants. “There has been a good spirit of cooperation on both sides. … We can learn from each other … Mutual learning, it adds to the level of competence.”117 “We have had good cooperation for a long time.”118 In contrast to the global and regional agreements, the bilateral Barents Agreement “makes this cooperation more detailed, more adjusted to the local situation between the two countries, it commits the parties a bit more…”119 Moreover, the frequency of communication between the parties has increased over the years.120 In addition to daily activities, there are weekly communication checks.121 “[T]here is continuous progress in the relationship with the Norwegians. To start with, communication was rather rare, but it has become more and more frequent every year. Communicating with the same people creates predictability, you know what to expect from the person.”122

The bilateral training exercises have proven a key facilitator of cooperation, and our informants agree that the exercises have been the main factor for success.123 Initially, the bilateral exercises were held on a smaller scale. However, the task complexity, the levels and amounts of resources involved have increased substantially.124 Though most informants highlight the positive impacts of the bilateral training exercises, a representative of the Norwegian Joint Headquarters made several critical points regarding Exercise Barents.125 This informant held that scenarios have been unrealistic in terms of weather conditions and the close proximity of incidents to land, with ready access to SAR resources; further, the informant pointed out that Russian SAR participation was limited to rescuing someone at predefined coordinates and with all necessary resources available. Thus, the exercises have done little to test the actual capacity and availability of SAR resources and thereby identify gaps. The primary value this informant saw in conducting Exercise Barents was to maintain communication between Norwegian and Russian participants. Another informant – a representative of the Norwegian Ministry of Justice and Public Security – commented that “challenges emerge” in cooperation, that “exercises can be a bit challenging” and “language and culture are a clear barrier” – while stressing that “our experience is that the cooperation with Russia is very good.”126

One shortcoming of the exercises is the absence of a joint formal evaluation procedure. After Exercise Barents, the parties have a common debriefing session, but there is no joint formal evaluation report following the exercise. Apart from the planning and pre-exercise meetings, no other regular meetings are held by the parties. Communication is limited to some day-to-day contact between the Joint Rescue Coordination Center (JRCC) in Bodø and Marine Rescue Coordination Center in Murmansk.

The absence of a joint evaluation procedure is due to the lack of capacity and funding.127 However, a common evaluation could make the cooperation more effective.128 The post-exercise debriefing sessions have now become the main arena for discussing experiences. Previously there was little discussion and criticism during debriefing, whereas now “[w]e trust each other more and can speak more freely.”129 When learning processes rely heavily on informal procedures, much will often depend on participant continuity, which has largely been stable. However, learning will not always disseminate among the participating actors – MRCC, JRCC, coast guards, coastal administrations, navies etc. – if procedures are not formalized.

From interviews and reports, challenges have been identified related to SAR cooperation under the agreement. Border-crossing procedures for SAR resources is one such issue.130 Border-crossing is important for the effectiveness of any joint SAR operation and is on the agenda during the exercise every year. Our Russian informant noted that “[w]hile getting permission [for border-crossing] could take hours before, now it only takes minutes.”131 However, the JRCC report on Exercise Barents 2014 emphasizes that “sometimes border crossing clearance of vessels is not possible, [which] might challenge the search pattern planning procedure.”132 Representatives of the JRCC underline that the situation has improved but remains an issue:133 “We fill in the forms and send them to the Russian side and it varies. That’s the problem. One year we get an answer within 15 minutes, the next year it takes 6 hours. The Russians say they need to wait for clearance from Moscow. The problem for us is that this varies a lot, differs from year to year, and it is hard to find out what the real problem is.”134

Our Norwegian informants also perceive it as a problem that they are not provided with an overview of resources on the Russian side regarding where they are based, their availability, how they can contribute.135 As one Norwegian informant pointed out: “We have tried for many, many years to … either get a map or a list or whatever. We have provided [information] on all of the Norwegian helicopters and vessels …, where they are normally, but they have never given us anything,” which creates a sense of unpredictability and has implications for planning.136 It was noted that one explanation made by Russian partners is that the Russian authorities are reluctant to share information regarding SAR resources that are under military command.137 The lack of information regarding available SAR resources is obviously an impediment to the effectiveness of joint SAR operations in terms of planning, mobilizing, and coordinating all available units and resources.

The language barrier used to be a substantial obstacle to effective communication and cooperation.138 Russia then started including English-speaking crewmembers on vessels. In addition, most controllers at the MRCC now speak English.139 As noted by a Norwegian informant: “It’s no problem for us today, I can pick up the phone, call Murmansk, most of them can speak English, it’s kind of an easy cooperation – yes, the Agreement works in that respect.”140 Consequently, the “language issue” has improved in recent years,141 but language is still considered a problem,142 particularly on site.143

Finally, some Norwegian informants noted that cooperation has sometimes relied on Norwegian resources called upon by MRCC or directly by Russian vessels.144 The reason given was that Russian resources are often not available when needed.145 As a representative from JRCC noted:

What we experienced a few years ago was that more and more Russian vessels contacted us even though they knew they were in the Russian area. … The rumors spread that if you contact Bodø you will get help. … We tried to transfer all of these to Murmansk. We use the system as it’s supposed to be used. … We don’t want to make a system where everybody contacts Norway wherever they are, because that undermines Russia.146

Such cases commonly involve requests for assistance from Norwegian SAR helicopters to assist Russian fishing vessels in distress, or in airlifting Russian fishermen who are ill or injured and need hospital care. They are not, as such, requests for assistance in joint SAR operations, which is the proper scope of the Barents SAR regime. However, it is likely that such day-to-day communication, and cooperation through the joint Barents SAR regime, have a mutually positive effect in maintaining dialogue and contacts.

Interestingly, Norwegian informants varied as regards the extent to which they trusted the effectiveness of the regime, and whether it would respond during actual SAR incidents. As one informant put it:

It’s not a problem for me to either call or send an e-mail to Murmansk to raise an issue if we find something problematic … or if we need to discuss anything. That’s easy and it’s of course due to the cooperation we have had all these years, that we have built up a kind of trust in each other. We know each other and we are able to communicate in a positive way.147

And, according to another: “We feel confident that we can cooperate. We know whom to call. We know what they have more or less”148. However, two JRCC representatives said they were uncertain whether assistance would be forthcoming from Russia during a SAR operation.149 This uncertainty, regarding both the Russians’ capacity and ability to provide assistance during SAR operations, is of course a crucial point in assessing the effectiveness of the Barents SAR regime. Similar doubts were not expressed on the Russian side, which, as noted above, has relied on Norwegian assistance.

The Barents SAR Agreement is, as noted, a bilateral agreement with a relatively limited scope, based on the pre-existing international framework. It has established procedures for requesting SAR assistance, border-crossings and information sharing between the parties. No formal decision-making body has been established under the Agreement. However, the joint meetings in connection with the annual Exercise Barents have provided an important arena for raising and resolving issues regarding SAR cooperation, both formally and informally. Over time, the operative cooperation of the parties has also developed, based on the annual Exercise Barents and the regular contacts between the JRCC and the MRCC. As such, development of the cooperation is largely based on operative aspects of the agreement, through joint planning meetings and exercises.

When assessing the performance of the Arctic and Barents SAR regimes there are no clear-cut answers that stand out. Through investigating the regimes’ paths of development and the challenges they face, we seek a nuanced understanding of the cooperation between the parties. When discussing the effectiveness of the Arctic and Barents SAR regimes we return to the analytical distinction between regimes outputs, outcomes and impact.150

In terms of regime outputs, the parties to the Arctic and the Barents SAR regimes have taken initial steps to make the regimes operational. The agreements enter into force as they are adopted and ratified by the parties. Both the Arctic SAR Agreement and the Barents SAR Agreement are based on, and nested within, well-established and widely recognized sources of international law: the 1979 SAR Convention, the 1944 Chicago Convention, the IAMSAR Manual, and UNCLOS 1982. The parties have acted in line with their international commitments by establishing specific SAR Agreements for the Arctic and Barents regions as the perceived need for such arrangements has developed. The Arctic and Barents SAR Agreements both establish procedures for cooperation, rights and duties, and not least mutual expectations regarding joint SAR operations within their mandate areas. However, the Arctic SAR Agreement has generated no new formal requirements/legal obligations for the parties, instead reaffirming the commitments of the Arctic states to the international regulatory framework. The same can be said for the Barents SAR Agreement. For example, both Agreements make it clear that the duty to assist and the levels of resources committed in a joint operation are subject to the availability of relevant resources. At the operational level, both regimes follow the established international framework which is already in place and governs SAR operations – in particular the IAMSAR Manual. As such, the two agreements do not add more stringency or new demands that could contribute to the effectiveness of the two regimes.151

Regime outcomes are related to the implementation of a regime and the extent to which it leads to behavioral changes.152 In general, the parties to the regimes seem to have a will to act upon the obligations established by the constituting agreements. However, there are challenges that need to be resolved both to facilitate cooperation and to promote behavioral changes. The Arctic and Barents SAR regimes do not establish any independent organizational capacity, such as a secretariat with a dedicated personnel and budget. In the case of the Barents regime, this is to be provided by the two member-countries and their national authorities. In the case of the Arctic regime, this responsibility to some extent falls under the EPPR. The Arctic SAR regime has established the advisory SAR Expert Group under EPPR. The Barents SAR regime has an established planning group. However, neither regime has a formal decision-making body that meets on a regular basis with the mandate to make decisions on behalf of the parties. The SAR Expert Group was established to promote, advise and assist the cooperation of the parties, not to make decisions. This was determined after an evaluation of Arctic Zephyr in 2015, where it was concluded that the parties were not acting upon their obligations to conduct meetings and cooperate under the Arctic SAR Agreement’s articles 9 and 10. As for the Barents regime, it has established a planning group in relation to the annual Exercise Barents, but that planning group is not mandated to make decisions on behalf of the member-states. As such, both regimes seem to have limited the capacity of members to make joint decisions to further cooperation.

The operative component of the Barents SAR Agreement appears stronger than that of the Arctic SAR Agreement, as the procedures established (joint training exercises and meetings of the exercise planning group) are up and running on a regular basis. Here the time difference should be recalled: the Barents SAR Agreements dates back to 1995, whereas the Arctic SAR Agreement was not concluded until 2011 and is still in the process of developing operative procedures. For both the Arctic and the Barents SAR regimes, exercises seem to be the centerpiece of practical cooperation. Exercises held in connection with the Arctic SAR regime are pivotal for mapping gaps and developing procedures and arrangements for its response systems to become functional. Without the exercises, the Arctic SAR Agreement would not have moved beyond being a “dead letter.” For the Barents SAR regime, all institutional arrangements focus on the annual exercises, and cooperation based on these planning meetings and exercises are what provides regime dynamics. A strong sense of trust and professional understanding has developed between the participants in the planning group. This has been an important factor for the positive development of the regime, in terms of dealing with practical and operational aspects of cooperation. However, the joint exercises of the regimes have also identified a range of challenges for operative cooperation. There has been criticism of the Norwegian-Russian bilateral exercises in that they do little to test the actual capacity of responders and the availability of SAR resources. In addition, the Barents SAR regime does not have joint evaluation procedures after exercises. Despite the parties’ positive dialogue and trust during debriefs, this impedes the mutual learning processes from joint operations and eventually the effectiveness of the regime.

All the Arctic states, parties to both regimes, are developing their national SAR capacities. Nevertheless, both regimes lag behind in terms of available SAR capacity within their mandate areas – not surprising, given the substantial increase in activity in the Arctic in recent decades. However, there is an acknowledged need to expand the capacity to conduct SAR operations. For the Barents regime, our study has shown that the Norwegian authorities have limited knowledge of Russian resources and their availability, or Russian procedures on notification and mobilization. For the Arctic regime, there is also a need to map available SAR resources among the parties. As such, there is limited insight in the actual SAR capacities available.

For the Barents SAR regime, problems also remain regarding the border-crossing procedures of SAR resources, in particular on the Russian side. This is a crucial issue that must be dealt with in connection with any large-scale international SAR operation that requires the mobilization of resources covered by the agreements. As the Barents and Arctic regions are geopolitically sensitive, and military units frequently the most readily available resources during SAR operations (planes, vessels, helicopters), this may also prove to be a challenge in the future. Notably, the main challenges related to information sharing and border crossing are not due to the participating actors involved in the cooperation. Border crossing may be hampered by national border authorities that do not participate in cooperation though the SAR regimes. In addition, information sharing regarding military units used in SAR operations may be considered sensitive information by military authorities. This is not surprising considering that both regimes include members of NATO and Russia. Finally, language is still a barrier regarding communication. Although the situation is improving, it has been reported by informants and in evaluation reports.

Regimes’ impact, that is, their problem-solving capacities, is subject to a great deal of uncertainty. Analytically, Andresen states that establishing indicators for regime impacts is riddled with uncertainties.153 In the case of the regimes analyzed here, impact would imply some measure of the regimes’ ability to conduct a joint response in a coordinated and effective manner. This study is largely based on the experiences of cooperation through joint exercises, and in the case of the Barents SAR regime, joint SAR operations. Based on the empirical findings in this study, one may conclude that the Barents SAR regime’s impact is uncertain, while the Arctic SAR regime’s score is low. One simple explanation is related to capacity - the human and technical SAR resources available. It is widely recognized that SAR capacity in the Arctic is low. In addition, there is uncertainty regarding the available capacity between different Arctic States, in particular Russia. Finally, the operational procedures, e.g. for communication and border-crossing, need to be formally established and predictable. In sum, this leads to uncertainties regarding the ability of the parties to the regimes to conduct joint SAR operations in an effective manner within their respective mandate areas, the purpose for which they were established.

SAR in the Arctic are complex operations involving a wide range of actors with specialized human and technical resources. Due to the limited resources and infrastructure available, international cooperation is a prerequisite to provide for SAR in the Arctic. We have analyzed two established regimes in the region, the Arctic and Barents SAR regimes, by applying analytical concepts for analyzing regime effectiveness. In doing so we have distinguished between the outputs, outcomes and impacts of the regimes. Further, we have focused on the experiences of cooperation and developments of the regimes, focusing not only on political dimensions of cooperation, but also on experiences of operative cooperation.

We conclude that the Arctic SAR regime is still under implementation. A constituting agreement has been negotiated and entered into force. However, a series of steps need to be taken to ensure that the regime leads to behavioral changes among the parties. This includes institutionalized cooperation through the regular meetings of parties, and the development of principles, rules and procedures for operational cooperation. Efforts are being undertaken by the parties in that regard, including the establishment of the SAR Expert Group and conducting joint exercises. However, these processes are likely to take time to develop. Consequently, it is premature to discuss the problem-solving capacity of the Arctic SAR regime at this point of time.

For the Barents SAR regime, the parties have developed their cooperation over time, through exercises and SAR operations. The constituting agreement is based on the established legal framework and acted upon by the parties. Through experience with operative cooperation, the regime has had a gradually increasing positive effect on the behavior of the parties. This has both been through formal modes of cooperation and more informal relations developed between the participating responders and agencies. However, informants are divided in their views regarding whether the regime is capable of handling joint SAR operations in a sharp situation. This is largely due to uncertainties regarding the availability of SAR resources in Russia and complications related to border-crossings.

Our findings call for caution in treating effectiveness in terms of a causal link between output, outcome and impact, where one is the starting-point for analyzing the following stages.154 In particular regarding the stringency and level of demands placed on the parties as a starting point for an analysis of effectiveness,155 which does not appear to be fruitful in these cases. Rather, operational cooperation, with a focus on exercises, seem to be the centerpiece of the two regimes. One consequence is that the political dimension of cooperation, through an institutionalized decision-making body, seems to be of lesser importance in the development of the regimes. This is particularly the case for the Barents SAR regime, but it also applies to the Arctic SAR regime. Moreover, the norms, principles, rules and procedures of the regimes are based on well-established and widely recognized international bodies of international law (SAR 1979, IAMSAR). In practice, the issues the parties are seeking to come to terms with are related to the complexity of the tasks and operational conditions involved in conducting SAR operations in the Arctic. In the Arctic SAR regime, this is related to putting in place the basic principles, rules and procedures for conducting joint SAR operations. The exercises have identified a wide range of challenges, indicating that the professional standards and procedures, platforms of communication, formal structures and more, are not yet coordinated and/or compatible to a satisfactory extent. For the Barents SAR regime, the development of cooperation, shared understandings and mutual expectations between responders at the agency level has been a major driving force. This is a result of shared professional standards as well as more informal relations - as reflected by the informants. These relations have developed gradually over time, and are not without complications. However, they have become important in facilitating cooperation between the parties.

Publication of this article has been made possible by a grant from the publication fund of UiT – The Arctic University of Norway.

1. Arctic Council, Arctic Marine Shipping Assessment, 2009 Report, April 2009; Charles Emmerson, Arctic Opening: Opportunity and Risk in the High North (London: Lloyd’s and Chatham House, 2012); Bjørn Gunnarsson, “The Future of Arctic Marine Operations and Shipping Logistics,” in The Arctic in World Affairs: A North Pacific Dialogue on the Future of the Arctic, eds. Oran R. Young, Jong Deog Kim, and Yoon Hyung Kim, 37–115 (North Pacific Arctic Conference Proceedings, joint publication of the Korea Maritime Institute and the East–West Center, 2013); Gunnar Sander et al., “Changes in Arctic Maritime Transport,” in Strategic Assessment of Development of the Arctic: Assessment Conducted for the European Union, eds Adam Stępień, Timo Koivurova and Paula Kankaanpää (Arctic Centre, University of Lapland, 2014); Yngve Antonsen et al., SARiNOR WP3 “SØK”, NORUT Report 11/2015 (Norut, Lufttransport and UIT, the Arctic University of Norway). http://norut.no/sites/default/files/norut_rapport_2015_15_sarinorwp3.pdf. Accessed June 07, 2017.

2. Sander, Gunnar et al., “Changes in Arctic Maritime Transport.”

3. Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, The High North: Visions and Strategies. Meld. St. 7 (2011–2012) Report to the Storting (White Paper).

4. Katarzyna Zysk. “Russia Turns North, Again: Interests, Policies and the Search for Coherence,” in Handbook of the Politics of the Arctic, eds. Leif Christian Jensen and Geir Hønneland (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, 2015), 437–461; Anatoli Bourmistrov et al., International Arctic Petroleum Cooperation: Barents Sea Scenarios (London: Routledge, 2015), 291.

5. Arctic Council, Arctic Marine Shipping Assessment; Sander et al., “Changes in Arctic Maritime Transport,” Alexei Bambulyak, Bjørn Frantzen, and Rune Rautio, Oil Transport from the Russian Part of the Barents Region: 2015 Status Report (Norwegian Barents Secretariat and Akvaplan-niva Norway).

6. Arctic Council, Arctic Marine Shipping Assessment; Juha Jokela ed., Arctic Security Matters, Report 24, June 2015 (Paris: Institute for Security Studies).

7. Antonsen et al. SARiNOR WP3 “SØK”.

8. For initial studies of SAR cooperation in the Arctic, see Shih-Ming Kao, Nathaniel S. Pearre, and Jeremy Firestone, “Adoption of the Arctic Search and Rescue Agreement: A Shift of the Arctic Regime Toward a Hard Law Basis?” Marine Policy, 36 (3) (2012): 832–836; Anne Toft Sørensen, “From International Governance to Region Building in the Arctic?” New Global Studies 7 (2) (2013): 155–182; Yoshinobu Takei, “Agreement on Cooperation on Aeronautical and Maritime Search and Rescue in the Arctic: An Assessment,” Aegean Review of the Law of the Sea and Maritime Law (2013) 2: 81–109; Anton Vasiliev. “The Agreement on Cooperation on Aeronautical and Maritime Search and Rescue in the Arctic – A New Chapter in Polar Law,” in Polar Law Textbook II (2013), ed. Natalia Loukacheva, 53–65; Michał Łuszczuk, “Regional Significance of the Arctic Search and Rescue Agreement,” Rocznik Bezpieczeństwa Międzynarodowego 8 (1) (2014): 38–50; Svein Vigeland Rottem, “The Arctic Council and the Search and Rescue Agreement: the Case of Norway,” Polar Record, 50 (254) (2014): 284–292; Svein Vigeland Rottem, “A Note on the Arctic Council Agreements,” Ocean Development and International Law 46 (1) (2015): 50–59.

9. Agreement on Cooperation on Aeronautical and Maritime Search and Rescue in the Arctic, Nuuk, Greenland, 12 May 2011, entered into force 19 January 2013. “Arctic Council,” https://oaarchive.arctic-council.org/handle/11374/531. Accessed January 17, 2017.

10. Avtale mellom Norge og Russland om samarbeid ved ettersøking av savnede og redning av nødstedte mennesker i Barentshavet, undertegnet 5. oktober 1995 (Barents SAR Agreement). “LOVDATA,”. https://lovdata.no/dokument/TRAKTAT/traktat/1995-10-04-1. Accessed January 17, 2017.

11. See for example Shih-Ming Kao, Nathaniel S. Pearre, and Jeremy Firestone, “Adoption of the Arctic Search and Rescue Agreement: A Shift of the Arctic Regime Toward a Hard Law Basis?” Marine Policy, 36 (3) (2012): 832–836; Yoshinobu Takei, “Agreement on Cooperation on Aeronautical and Maritime Search and Rescue in the Arctic: An Assessment,” Aegean Review of the Law of the Sea and Maritime Law (2013) 2: 81–109.

12. See for example Svein Vigeland Rottem, “The Arctic Council and the Search and Rescue Agreement: the Case of Norway,” Polar Record, 50 (254) (2014): 284–292; Heather Exner-Pirot, “Defence Diplomacy in the Arctic: the Search and Rescue Agreement as a Confidence Builder,” Canadian Foreign Policy Journal, 18 (2) (2012): 195–207.

13. See for example http://www.nord.no/no/om-oss/fakulteter-og-avdelinger/handelshogskolen/senter/nordomradesenteret/Sider/MARPART.aspx#&acd=65ff82a3-421e-73fe-2b69-39962d53d29a Accessed May 5, 2017.

14. Are Kristoffer Sydnes and Maria Sydnes, “Norwegian–Russian Cooperation on Oil-spill Response in the Barents Sea,” Marine Policy, 39 (2013): 257–64.

15. Arild Underdal and Oran R. Young, eds., Regime Consequences: Methodological Challenges and Research Strategies (Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic, 2004), 394.

16. Marc A. Levy, Oran R. Young, and Michael Zürn, “The Study of International Regimes,” European Journal of International Relations 1 (3) (1995): 267–330, at 274.

17. Olav Schram Stokke, “The Interplay of International Regimes: Putting Effectiveness Theory to work,” FNI Report No. 14/2001 (Oslo: Fridtjof Nansen Institute).

18. Robert Axelrod and Robert O. Keohane. “Achieving cooperation under anarchy: strategies and institutions,” in Cooperation under Anarchy (1986), ed. Kenneth A. Oye, 226–254, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

19. Peter M. Haas, “Introduction: Epistemic Communities and International Policy Coordination,” International Organization, 46 (1) (1992): 1–35; Sydnes and Sydnes, “Norwegian–Russian Cooperation on Oil-spill Response”.

20. Arild Underdal. “Methodological challenges in the study of regime effectiveness,” in Regime Consequences: Methodological Challenges and Research Strategies (2004), ed. Arild Underdal and Oran R. Young, 27–48, Doedrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers; Arild Underdal, “The Concept of Regime Effectiveness,” Cooperation Conflict, 27 (1992): 227–240; Oran R. Young and Marc A. Levy (with the assistance of Gail Osherenko). “The effectiveness of international Environmental regimes,” in The Effectiveness of International Environmental Regimes: Causal Connections and Behavioral Mechanisms (1999), ed. Oran R. Young, 1–32, Cambridge: MIT Press.

21. Oran R. Young. “The consequences of international regimes: a framework for analysis,” in Regime Consequences: Methodological Challenges and Research Strategies (2004), ed. Arild Underdal and Oran R. Young, 3–23, Doedrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers; Steinar Andresen. “International Regime Effectiveness,” in The Handbook of Global Climate and Environmental Policy (2013), ed. Robert Falkner, 304–319, Chichester: John Wiley & Sons.

22. Arild Underdal. “One question, two answers,” in Environmental Regime Effectiveness: Confronting Theory With Evidence (2002), ed. Edward L. Miles, Arild Underdal, Steinar Andresen, Jørgen Wettestad, Jon Birger Skjærseth, and, Elaine M. Carlin, 3–45, Cambridge: MIT Press: 6–7.

23. Steinar Andresen. “International Regime Effectiveness,” in The Handbook of Global Climate and Environmental Policy (2013), ed. Robert Falkner, 304–319, Chichester: John Wiley & Sons.: 309.

24. Arild Underdal. “One question, two answers,” in Environmental Regime Effectiveness: Confronting Theory With Evidence (2002), ed. Edward L. Miles, Arild Underdal, Steinar Andresen, Jørgen Wettestad, Jon Birger Skjærseth, and, Elaine M. Carlin, 3–45, Cambridge: MIT Press.

25. Oran R. Young, “Evaluating the Success of International Environmental Regimes: Where are We Now?” Global Environmental Change, 12 (1) (2002): 73–77.

26. Oran R. Young. “The consequences of international regimes: a framework for analysis,” in Regime Consequences: Methodological Challenges and Research Strategies (2004), ed. Arild Underdal and Oran R. Young, 3–23, Doedrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

27. Arild Underdal. “Methodological challenges in the study of regime effectiveness,” in Regime Consequences: Methodological Challenges and Research Strategies (2004), ed. Arild Underdal and Oran R. Young, 27–48, Doedrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

28. Steinar Andresen. “International Regime Effectiveness,” in The Handbook of Global Climate and Environmental Policy (2013), ed. Robert Falkner, 304–319, Chichester: John Wiley & Sons.: 310.

29. Steinar Kvale and Svend Brinkmann, Interviews: Learning the Craft of Qualitative Research Interviewing, 2nd edition (Los Angeles CA: Sage, 2009), 376.

30. Hsiu-Fang Hsieh and Sarah E. Shannon, “Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis,” Qualitative Health Research 15 (9) (2005): 1277–88.

31. “Maritimt forum Nord”. http://www.sarinor.no/?ac_id=348&ac_parent=1. Accessed January 17, 2017.

32. Yoshinobu Takei, “Agreement on Cooperation on Aeronautical and Maritime Search and Rescue in the Arctic: An Assessment,” Aegean Review of the Law of the Sea and Maritime Law (2013) 2: 81–109.

33. United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, Montego Bay, 10 December 1982, entered into force 16 November 1994, United Nations Treaty Series, 1833 (LOSC), Article 98, 2.

34. “International Maritime Organization (IMO),” http://www.imo.org/About/Conventions/ListOfConventions/Pages/International-Convention-for-the-Safety-of-Life-at-Sea-(SOLAS),-1974.aspx. Accessed January 18, 2017.

35. International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea, 1974. United Nations Treaty Series, 1184, Chapter 5, Regulation 10 (a).

36. International Convention on Maritime Search and Rescue, 1979. United Nations Treaty Series, 1405.

41. Convention on International Civil Aviation (the Chicago Convention 1944), signed at Chicago 7 December 1944, entered into force 4 April 1947.

42. “International Maritime Organization (IMO).”

43. Arctic Council, Arctic Marine Shipping Assessment.

44. International Code for Ships Operating in Polar Waters (the Polar Code). IMO Doc. Resolution MSC.385(94).

46. Ibid.. Ch. 2, 2.3., 2.3.1.

47. Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The High North: Visions and Strategies, 110.

48. Canada, Denmark (Greenland, Faroe Islands), Norway, Sweden, Finland, Island, Russia, and the USA.

49. Nuuk Declaration on the Occasion of the Seventh Ministerial meeting of the Arctic Council, 12 May 2011, Nuuk, Greenland (Arctic Council 2011).

50. “Arctic Council,” http://www.arctic-council.org/index.php/en/our-work/agreements. Accessed January 20, 2017.

52. A detailed overview is provided by Takei, “Agreement on Cooperation on Aeronautical and Maritime Search and Rescue in the Arctic,” 84.

53. EPPR Working Group Meeting. Final Report. Whitehorse, Yukon, Canada, June 15–16, 2011 (Arctic Council, 2015), http://arctic-council.org/eppr/wp-content/uploads/2011/09/EPPR-Working-Group-Meeting-Final-Report%209-10-11.pdf. Accessed January 20, 2017.

55. Anton Vasiliev. “The Agreement on Cooperation on Aeronautical and Maritime Search and Rescue in the Arctic – A New Chapter in Polar Law,” in Polar Law Textbook II (2013), ed. Natalia Loukacheva, 53–65.

61. Ibid., Article 7, para 3(e).

62. Ibid., Article 12, para 2.

63. Ibid., Article 12, para 1.

71. Ibid., Article 15, para 1.

72. Ibid., Article 15, para 2.

74. Ibid., Article 19, para 3.

75. “Arctic Council,” http://www.arctic-council.org/eppr/ Accessed 20 January 2017.

76. EPPR Strategic Plan, Approved by the Senior Arctic Officials in Fairbanks, March 16, 2016. Emergency Prevention, Preparedness and Response Working Group (EPPR), Objective 5.

78. Ibid; EPPR Working Group meeting, May 26–28, Longyearbyen, Svalbard, Norway, Final report. Emergency Prevention, Preparedness and Response Working Group (EPPR) 2015.

79. EPPR Strategic Plan, Approved by the Senior Arctic Officials in Fairbanks, March 16, 2016. Emergency Prevention, Preparedness and Response Working Group (EPPR), Objective 5.

80. “Emergency Prevention, Preparedness and Response (EPPR)”. http://www.arctic-council.org/index.php/en/about-us/working-groups/eppr. Accessed 20 January 2017.

81. Rapport fra EPPR II møtet i København 6.-8. 12, 2016. Kystverket, 2016.

82. “Arctic Council,” http://www.arctic-council.org/index.php/en/our-work2/8-news-and-events/409-eppr-montreal-2016. Accessed 20 January 2017.

83. Rapport fra EPPR II møtet, Kystverket, 2016.

84. “Arctic Council,” http://www.arctic-council.org/eppr/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/2016-12-06-draft-SAR-EG-mandate-text_edited-SAREG.pdf Accessed 05 May 2017.

87. 2015 Year in Review: Progress Report on the Implementation of the National Strategy for the Arctic Region. Executive office of the President of the United States (Arctic Executive Steering Committee, 2015): 27.