1. Introduction

In contrast with similar documents previously issued by the EU, the updated version of the European Union’s Arctic policy published in the autumn of 2021 focuses strongly on geopolitical interests. In connection with challenges deriving from cryosphere loss and diverse stakeholders’ growing interests in Arctic resources, the EU considers its “full engagement in Arctic matters [as] a geopolitical necessity” due to the global impacts of such trends.1 This more assertive engagement in the Arctic region is relatively recent, and the role of the EU is contested by several stakeholders.

The European Economic Community (EEC) originally had ties with the Arctic region through Greenland, as part of the Kingdom of Denmark. However, conflicts about fishing and hunting led Greenland to leave the EEC in 1985. When the EU was formed in 1993, it thus lacked natural links to the Arctic and the region disappeared from its political agenda. After Sweden and Finland joined the Union in 1995, the EU gained a formal link to the Arctic region, but its engagement remained “uncoordinated and ad hoc” until 2007.2 Climate change, highlighted by the Arctic Ocean sea ice minimum of 2007 and 2012 respectively, and growing political interest in the region’s resources and potential shipping routes, prompted the European Commission to initiate a concerted effort to develop an Arctic policy.

This increasing international interest in the Arctic region coincides with a heightened focus on foreign policy within the EU. Specifically, after the adoption of the Lisbon Treaty, the EU honed its foreign policy instruments by developing the position of High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy (HR) and creating the European External Action Service (EEAS) in 2009 and 2010 respectively.3 As described later, this has also led to a series of statements about the EU’s stance on the Arctic region.

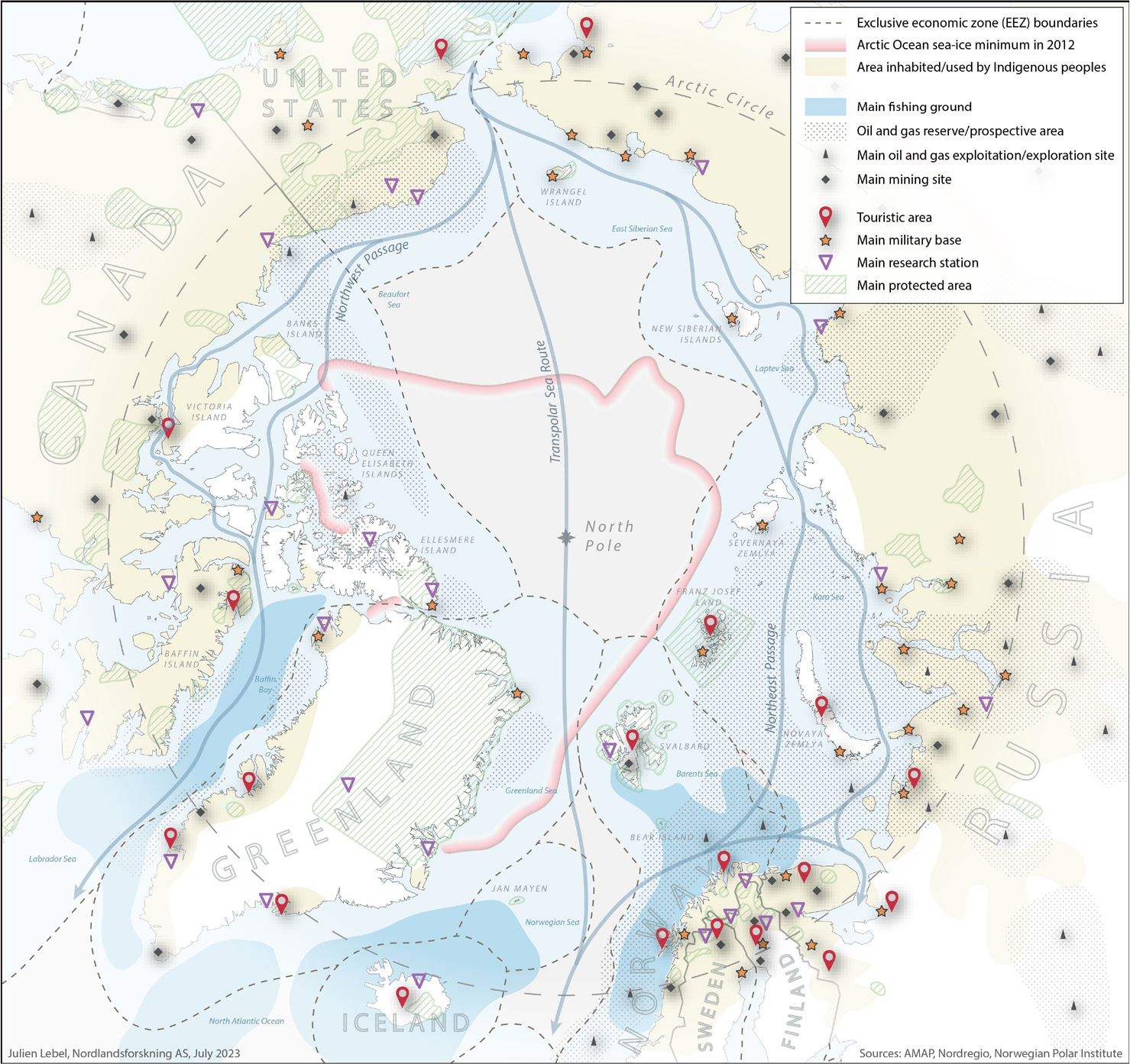

Though the EU has developed an ambitious Arctic policy, it has no jurisdiction in most of the region and thus lacks direct political power. This article therefore analyses how the EU can influence places outside its jurisdiction. Oberlack et al.4 argue that interconnected social-ecological systems can be affected by both proximate and distant actors, as they are shaped by factors and processes from various places. In a globalised world where transnational issues require updated strategies from stakeholders in different locations, the concept of telecoupling – which refers to interactions between distant systems – has gained interest and can be related to different fields, such as tourism, migration and trade.5 This approach is particularly relevant when considering the Arctic region as it is impacted by transnational dynamics and does not fall under the sovereignty of a sole country (figure 1). The topic of Arctic policy has been addressed in many recent publications, often focusing on particular aspects, such as governance, strategies and geopolitics,6 or specific actors, such as the EU,7 the United States,8 Russia9 or China.10 The EU’s ambitions should be seen against the backdrop of this changing geopolitical context and the renewed ambitions of many actors.

The analysis developed in this paper is based on a mapping of policy processes and international agreements that are relevant to both the EU and the Arctic region. The authors conducted an in-depth literature review focusing on activities in the Arctic region where the EU has specific interests or influence, namely fisheries, tourism, shipping, oil and gas exploration and exploitation, environmental protection and research. Interviews and meetings involving EU policymakers as part of the EU-funded research project called FACE-IT (“The Future of Arctic Coastal Ecosystems – Identifying Transitions in fjord systems and adjacent coastal areas”) have also contributed insights into EU Arctic policy development.

Figure 1. The Arctic region, a strategic area with multiple resources.

The first section of this article provides an overview of the evolution of the EU’s Arctic policy, detailing the political processes and mechanisms behind increasing EU engagement in the region. Interest in issues related to climate change has increased over the years, culminating in 2020 with the adoption of the European Green Deal, which is “at the heart of the EU’s Arctic engagement.”11 Meanwhile, the EU’s more assertive strategy has resulted in broader coverage of its Arctic policy, including security issues. The second section focuses explicitly on relations with Greenland and Norway/Svalbard. For the EU, these territories are highly strategic Arctic areas that have close ties to the EU without falling under its jurisdiction. The third section focuses on sectors the EU has influence over by analysing EU strategies in connection with fisheries, tourism, shipping, oil and gas exploration and exploitation, biodiversity and conservation, and finally, mitigation and adaptation regarding climate change.

In the discussion section we reflect upon the new geopolitical context in the Arctic in relation to the EU strategies in order to assess in which ways it may impact the EU’s ambitions. It is our belief that the EU’s contradictory goals could harm its legitimacy in engaging actively in the Arctic, both towards Indigenous peoples and third states. However, the EU remains a powerful stakeholder in setting trends in key areas that could significantly impact the Arctic,12 beyond policies directly targeting the region.

2. Evolution of the EU’s Arctic policy

Current EU interests in the Arctic stem from geopolitical changes following the 2007 Arctic Ocean sea ice minimum. This climate-driven event coincided with coastal states submitting claims for decisions about the outer limit of the continental shelves under Article 76 of the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). This created a political and media discourse about economic opportunities and access to oil and gas.13 During the same period, the European Commission was actively expanding its role in foreign policy. Thus, increased attention to climate change, a new maritime landscape, geopolitics, and the launching of an EU action plan for an integrated maritime policy contributed to bringing the Arctic Ocean to the foreground.14

In parallel with the Commission’s work, the EU Parliament voted in 2008 on a resolution that urged the Commission to take a proactive role in the Arctic and to prepare negotiations for an international treaty for its protection. This raised major concern among Arctic coastal states. Following the increase in international interest, Canada, the Kingdom of Denmark, Norway, Russia and the United States signed the Ilulissat Declaration, which proclaimed their view of Arctic governance with a focus on their special role as coastal states under the Law of the Sea.15 When the Commission’s report was presented in November 2008, the controversial focus on potentially drafting an Arctic treaty was not visible. Instead, other topics were emphasised, especially multilateral governance and the sustainable use of natural resources.16

The ambition to contribute to multilateral governance as detailed in the EU’s 2008 report was expressed as being an effort to gain permanent observer status in the Arctic Council. So far, the EU has not achieved this goal, as Canada in 2009 and later Russia expressed their opposition,17 in the former case due to the EU’s plan to ban seal products from its markets and in the latter case due to EU’s criticism of the annexation of Crimea in 2014. Though the EU’s lack of permanent observer status in the Arctic Council did not have major practical implications given that the EU remained an ad hoc observer, it initially had “huge symbolic value.”18 However, the geopolitical situation has shifted dramatically following Russia’s aggressive invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, which has led to a halt on all formal Arctic Council activities.

Over the years, the EU’s Arctic policy has been further clarified and become more nuanced in Joint Communications and a Council Conclusion.19 In 2020, the EU launched a consultation on the future approach of the EU Arctic policy,20 and on 13 October 2021, the updated policy was presented.21 The 2021 Arctic policy includes earlier priorities on climate change, research, and sustainable and inclusive development, but also features a strong focus on EU’s geopolitical security interests and the Green Deal.

This geopolitical focus, presented for the first time in a dedicated chapter of an Arctic policy document written by the EU, has two separate priorities: gaining access to the critical minerals needed for transitioning away from fossil fuels22 and the traditional concerns of keeping the Arctic region as a peaceful and safe place in the face of new geopolitical tensions globally, especially new assertiveness from Russia and China. Though the EU has a clear ambition to become a geopolitical actor in the Arctic, interviews with EU officials suggest that it does not intend to be a “hard security” player. The situation is nevertheless evolving as Finland and Sweden have recently joined the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) alliance, while Russia has been leading a remilitarisation in the Arctic since before its invasion of Ukraine.

In line with the Green Deal ambition to move away from fossil fuels, the EU policy also includes a commitment to keep fossil fuels in the ground.23 This goal brought immediate negative reactions from some actors, including a comment made by the Arctic Economic Council to not meddle in Arctic business development24 while the EU is still dependent on oil and is responsible for greenhouse gas emissions. This more assertive EU stance illustrates how stronger geopolitical ambitions and Green Deal priorities may have political implications for the EU’s legitimacy as an Arctic actor.

3. Relations with key territories in the Arctic: Greenland and Norway/Svalbard

3.1 Relations with Greenland

Relations between Greenland and the EU are closely tied to Greenland’s process of decolonisation, including the 1979 referendum in which a large majority of Greenlanders voted for Home Rule as a direct result of Denmark joining the European Economic Community. In 2008, this was followed by a referendum on self-government, which was accepted by the Danish Parliament in 2009. After leaving the European Community in 1985, Greenland gained “overseas country or territory”25 status which has served as a base for a bilateral fisheries agreement with the EU.26 This initial agreement was extended, and in 2015, the EU, Greenland, and Denmark signed a joint declaration focusing on various topics including natural resource management, education and research, and environment and biodiversity. Further illustrating the developing ties between Greenland and the EU, several sector-specific agreements have followed, such as a new fisheries partnership in 2021 and a memorandum of understanding on raw materials in November 2023.27

In the 2021 EU Arctic policy, the EU expressed its desire to open an office in Nuuk to further support EU–Greenland collaboration.28 An opinion poll focusing on Greenlanders’ attitudes regarding foreign relations has concluded that, in general, foreign policy is not a prominent topic in public debate. Regarding their relations with the EU, Greenlanders would like to see more cooperation but are nevertheless not willing to become members of the Union.29

The 2009 EU prohibition on seal products in its markets was heavily criticised by Greenland and Canada. Though this regulation makes exceptions for products that come from hunts conducted by Inuit or other Indigenous communities, the ban strongly affected local communities.30 The literature on the impact of the EU’s seal skin regulations demonstrates that EU policies can impact resource management in Greenland, and that such impacts can also affect political relations.31

The future relationship between the EU and Greenland may be influenced by the fact that Greenland’s geology makes its territory a potential source of critical raw materials for transitioning to a non-fossil energy system.32 These are strategic resources not only in the eyes of the EU but also for China and the United States,33 thus placing Greenland into a larger geopolitical context that may affect EU–Greenland relations. Following the general election in 2021, the new government in Greenland supports developing the mining sector as part of its diversification strategy.

In her analysis of the legal frameworks for hydrocarbon development, Eritja34 highlighted that the EU’s policy frameworks for, and commitment to, protecting Indigenous peoples’ rights are poorly developed. These comments would be equally applicable to other raw materials and thus relevant for EU–Greenland relations in a green transition and for other areas where the EU’s strategic interests intersect with those of Greenlanders. In the new EU Arctic policy, the concept of “prior and informed consent” is, however, clearly stressed, along with continuous dialogue with diverse stakeholders at various levels. In stressing this, the EU seems to recognise the diversity of the local communities who have their own concerns and thus their own positions when it comes to resource extraction. Regarding exploration for hydrocarbon resources, in 2021, Greenland’s government dropped all plans for future oil exploration, citing climate concerns. Thus, its stance aligns with the EU’s ambitions.

3.2 Relations with Norway and Svalbard

Norway is not a member of the EU, and such membership has in fact been rejected in two referenda (in 1972 and 1994). This rejection has been attributed to “the EC’s poor track record in a few policy areas key to Norway, such as fisheries and agriculture.”35 In practice, and as a consequence of being party to the European Economic Area (EEA) agreement, Norway nevertheless complies with most EU legislation and has been characterised as “the most integrated outsider to the Union.”36

Via the EEA agreement, Norway has access to the single market and cooperates in a variety of policy areas. Not only has Norway entered into bilateral agreements with the EU and often joins the EU in foreign policy statements,37 but it is also a member of the Schengen Agreement and contributes financially to the EU. A major difference compared to EU member states is that Norway has no formal say in the EU’s decision-making processes. Furthermore, some policy areas are explicitly excluded, such as fisheries. The economic ties between Norway and the EU are strong, with EU countries making up Norway’s five largest export and import markets.38

Despite close cooperation and agreement on many issues, relations have not always been harmonious, especially on issues related to fisheries. The different interpretations of the Spitsbergen Treaty – or the Svalbard Treaty as it is often called39 – have led to disputes regarding Svalbard’s maritime zone. Norway officially gained sovereignty over Svalbard according to the terms of the Treaty, subject to certain conditions,40 including that Norwegian authorities cannot discriminate against or favour actors based on citizenship.

Whether the Treaty applies only to territorial waters or across the whole 200-nautical-mile maritime zone around Svalbard is a contentious question. Norway claims the former, but this has been disputed by other countries that desire equal rights to economic activities in the 200-mile zone.41 The EU as such is not party to the Treaty, but several of its member states have been engaged in diplomatic exchanges with Norway about the legal status of Norway’s claims.42

In 2015, the opposing views came to a head in a dispute over snow crab fishing after Norway imposed a ban on catching snow crabs on the Norwegian continental shelf and issued a limited number of licences only to Norwegian fishermen, thus excluding boats from EU countries. The matter is further complicated by the fact that, in 2011, Norway was granted rights to the extended Norwegian continental shelf under UNCLOS. Because this shelf extends to Svalbard, Norway claims to be the sole regulator of economic activity there, but this has been challenged based on the notion that the Spitsbergen Treaty should apply.43 In 2023, the Supreme Court of Norway ruled that the Spitsbergen Treaty does not apply to the continental shelf off Svalbard, asserting Norwegian sovereignty over the area and regulating de facto fishing activities for foreign vessels through quotas.44 Moreover, Norway and the EU also have different views on how EU quotas for Arctic cod should be calculated, leading the Directorate-General for Maritime Affairs and Fisheries (DG MARE) to express concerns regarding decisions from Norway and Russia that could lead to “an unsustainable fishing of the stock” in Arctic waters.45

Norway’s position in these disputes coincides with what has been described as an assertive stance in establishing a strong governance regime for Svalbard.46 It is also in line with Norway’s ambitious policies for its “High North” and for being a key player in circumpolar international politics. The diplomatic snags surrounding fisheries reflect general tension between the requirement under the Spitsbergen Treaty to not impose rules that discriminate other parties and the broadening of environmental governance that began in the 1970s.47 However, the deterioration of relations with Russia has led to a relative shift of focus regarding Arctic matters, as Norway and the EU currently share a common stance and concerns about the stability of the region.

4. Relevant sectors of influence for the EU

4.1 Fisheries

Arctic fisheries are an important seafood supply source for the EU as one of the world’s largest seafood markets. This includes imports from Greenland and Norway.48 Moreover, the large Arctic fish stock of cod, pollock, herring, haddock, and halibut are of interest to the fishing fleets of EU member states and are subject to fishery quota negotiations.49 Fishery issues have also been a common cause of contention between the EU and Arctic countries, and indeed a motive for Norway to remain outside Union membership.

While the EU only accounts for a small proportion of fish catches in the Arctic, the footprint of EU’s fish consumption is considerable and potentially growing, and was mentioned as a cause for concern in 2010.50 Recent assessments indicate that the status of fish stocks in the Northeast Atlantic has improved thanks to better management and decreased fishing pressure. However, continued efforts are needed to meet the EU’s 2020 objective for healthy fish and shellfish stocks in the region.51 The EU has, moreover, expressed concern about the sustainability of Arctic cod fisheries in the Barents Sea,52 as well as pressures from illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing, and unintended bycatch.

Increasing emissions and pollution from the fishing fleet are also a concern (notably emissions of black carbon), along with its substantial contribution to marine litter, including plastic pollution. Plastics in the Arctic have become a key issue for the Arctic Council, which endeavours to assess its impacts and to develop and put in place management plans.53 Koivurova et al.54 suggest that the EU could be a considerable source of microplastics in the Arctic, with fisheries being mentioned as one of several sources. They also highlight that micro and macro plastics affect animals in the Arctic and may affect whether Arctic fish is perceived as being a valuable and safe food source.

An additional concern for fisheries in the Arctic relates to greenhouse gas emissions and their potential negative impacts on fish stocks due to warming sea waters and acidification, though there is much uncertainty here. Shifts in distribution patterns from sub-Arctic to high latitude seas may attract modern fishing fleets further north and come into conflict with Indigenous peoples’ subsistence livelihoods along the Arctic coasts. This also has the potential of leading to political conflict in the management of fisheries. Furthermore, species associated with the seabed can end up as bycatch in conventional bottom-trawling equipment. Even if these species are not commercially valuable, many are important for the functioning of Arctic marine ecosystems.55

A specific aspect of climate impacts is the risk that declining sea ice will attract unregulated fishing in the Arctic Ocean. In 2018, the five Arctic coastal states together with the EU, China, Iceland, Japan, and Korea signed an agreement to prevent unregulated fisheries in the Central Arctic Ocean to address this concern.56 While activities in the Arctic Ocean are covered by international agreements on pollution, biodiversity, maritime issues, and rights to resources, the areas outside the Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZ) of the five Arctic coastal states are not included in national fishery regulations. Under the Common Fisheries Policy (CFP), the EU has authority to be a party to the 2018 Agreement due to its exclusive competence. Although it is uncertain whether fisheries in the Arctic Ocean will become commercially viable, Vylegzhanin et al.57 describe the agreement as being a sign of an emerging, broader governance system that emphasises preservation and protection of the Arctic environment and marine resources.

The EU’s CFP applies to all vessels fishing in European waters and to EU vessels fishing in non-European waters, thus including the Arctic.58 The purpose is to conserve marine biological resources and ensure that fisheries are sustainably managed. The CFP, and particularly its “discard ban” and “landing obligation”, is relevant for reducing unwanted bycatch. Liu and Kirk59 suggest that the EU could use its position as a major fishing market to also promote such measures for vessels other than those covered by EU policy. They also mention the possibilities of controlling imports from unsustainable fisheries, though such measures must be non-discriminatory and compatible with World Trade Organisation (WTO) rules.

4.2 Tourism

Tourism is increasingly relevant for economic development in the Arctic,60 where climate change with its glacial and sea ice retreat has spurred last-chance tourism.61 Increases in tourism could lead to economic leakage as well as social and environmental impacts locally,62 especially when cruise tourism floods local communities and popular attractions.63 The construction or the extension of transportation-related facilities, such as ports and airports, not only puts pressure on local ecosystems but will likely also lead to increased traffic and greenhouse gas emissions and a higher number of visitors. However, because tourism can also bring local income and improved infrastructure, perceptions of the risks and opportunities vary among local actors. Tourism therefore faces a greater diversity of risks than many other economic sectors,64 and its vulnerability to external shocks became very evident during the COVID-19 pandemic.

EU countries account for a significant share of tourists in the Arctic. In 2020, 44% of cruise tourists in Greenland were from EU-27 countries (including Denmark), and in 2019, EU countries accounted for 47% of the accommodation nights (excluding the United Kingdom and Denmark). In northernmost Norway and Svalbard, EU-27 accounted for 27% of foreign visitors.65 Aside from cruise ships, a significant number of visitors come to these places by plane, taking long-haul flights when travelling from other continents, which contributes to global greenhouse gas emissions. As Greenland and Svalbard are only reachable by a few air routes, travellers must often combine different flights and thus use ineffective itineraries that worsen air travel’s carbon footprint to the Arctic regions.

When it comes to policies, the EU does not have direct influence on tourism activities in the Arctic region. However, its climate and pollution policies may affect travel options, which would indirectly affect the amount of travel. The EU can potentially also influence the environmental impacts of travel and provide knowledge input to international organisations that guide tourism development in the Arctic. Although the EU cannot define specific environmental standards for tourism, it can encourage good practices. The future development of tourism may also be influenced by perceptions of the Arctic and of moral obligations to reduce travel and/or the sustainability impacts of travel, where the EU has a potential role as trendsetter, at least for European tourists. Indicators of sustainable tourism66 and eco-labels that are used for tourist destinations within the EU could also be relevant for other places in the Arctic.

4.3 Shipping

Fisheries and tourism are important contributors to shipping in the Arctic, as are goods and raw material transports, and research vessels. From 2013 to 2019, shipping in the Polar Code areas increased by 25%,67 most of which is attributed to fishing vessels. An important cause of the increase is extraction of natural resources, including ores, as well as oil and gas in the Arctic. So far, transpolar shipping is limited, despite Russia previously highlighting ambitious goals to develop shipping traffic on the Northern Sea Route to export hydrocarbon resources and to stimulate the use of an alternative waterway between Europe and the Pacific.68

Forty percent of the world’s shipping fleet sails under EU member state flags,69 and given that Europe is also an important market for raw materials from the Arctic, the EU is a relevant actor in relation to Arctic shipping. Shipping activities are covered by the EU’s Maritime Transport Strategy from 2009, in which the Arctic is only briefly mentioned with reference to the Commission’s Communication on the Arctic Region and its suggestions “for ensuring sustainable Arctic commercial navigation.”70 The 2021 Arctic policy update asserts that the EU and its member states will promote faster and more ambitious emission reductions from shipping in the International Maritime Organisation (IMO) and within the EU.71

Important impacts from shipping in the Arctic relate to pollution. These include the risk of oil spills and the risk associated with burning heavy fuel oil, the second of which has a substantial carbon footprint and is a source of black carbon in the atmosphere that has impacts on the climate and potentially on health. Another concern is the risk of accidents, both in relation to potential oil spills and to the risks to crew and passengers, since search and rescue capacities are limited and challenging in the Arctic region. International efforts to regulate shipping are coordinated by the IMO, which has adopted the Polar Code that entered into force in January 2017.72 This code complements a range of other legal instruments from the IMO and aims to reduce pollution risks related to shipping in ice-covered waters. In addition, the Arctic Council countries have entered into legally binding agreements on preventing and managing oil spills and on cooperating in search and rescue efforts.

The EU is not a member of the IMO nor party to the agreements among the Arctic countries. Nevertheless, it can potentially have indirect influence on the further development of maritime safety; in this regard, Liu and Kirk73 suggest coordinating the position of EU countries to construct a common EU position. Furthermore, they suggest that the EU can take internal action by strengthening its port controls related to carrying and using heavy fuel oil and enforcing existing legislation aimed at combatting invasive species from ballast water. In addition, Koivurova et al.74 highlight the possibility of using the EU’s emergency response capacities in Arctic waters, a suggestion that also appears in the 2021 Arctic policy update.

4.4 Oil and gas exploration and exploitation

The EU is dependent on imported oil and gas, a major share of which comes from the Arctic. In 2019, 46% of its natural gas was imported from Russia and 29% from Norway (Arctic and non-Arctic reported together in the statistics).75 The potential impact of oil and gas exploration on Arctic ecosystems ranges from physical disturbance of environments that are important for marine biodiversity, to noise, pollution, and increased shipping activities. While some impacts of oil and gas activities are covered by both general and Arctic-specific agreements, the EU has no jurisdiction over these activities in the national waters of the Arctic states. Liu and Kirk76 instead point to its role as a consumer of raw materials and actor in global energy politics. They suggest that the EU should promote an Arctic-specific, legally binding agreement on offshore oil and gas operations, containing the highest safety standards, using the guidelines prepared by the Arctic Council Working Group for the Protection of the Arctic Marine Environment (PAME) as a starting point.

The future impacts of oil and gas activities in the Arctic may depend on market demands for this resource. Therefore, the ambition to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and the EU’s Green Deal for hastening the transition from fossil fuels are highly relevant. However, the transformation of EU’s energy regime will likely lead to increased demand for other Arctic resources, both directly via electricity imports from expanding wind power, and indirectly via increasing demand for metals that are used in green technologies. The geopolitical context following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is also forcing the EU to shift the geographical origins of oil and gas imports.

A stronger focus on the extraction of hydrocarbons in the Arctic is thus expected in the short term. In September 2022, the Norwegian government decided unilaterally to extend coal mining on Svalbard until 2025, as, according to the Norwegian Minister of Industry, the coal is used in the production of steel in Europe.77 Nevertheless, the EU asserts that it wants to maintain its long-term goal of transitioning completely away from fossil fuels by 2050. Koivurova et al.78 propose that EU policymakers promote a comprehensive Arctic Energy Policy, which would be one step towards considering the complexity of the EU’s energy relationship to the Arctic and its potential implication for Arctic environments and societies.

4.5 Biodiversity and conservation

Even though the main threat to biodiversity in the Arctic is climate change,79 it is also subject to a range of other pressures. These include fishery and harvesting of marine resources as well as pollution and physical disturbances from human activities. The EU is committed to the goals of the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) including the Aichi Biodiversity Targets. The EU has also signed the Nagoya Protocol to the Convention on Biological Diversity, which provides a framework for access to and benefit-sharing of genetic resources. The mandatory aspects of the protocol were implemented in 2014.80

Given this commitment to protect biodiversity, the political grounds for measures aimed at preserving Arctic marine biodiversity are strong.81 However, the way of going about it is far from simple given the lack of jurisdiction in non-member states. Still, there are issues on which the EU can act, and in a review of the EU’s potential contribution to protecting Arctic marine biodiversity, Liu and Kirk82 highlight the potential of creating marine-protected areas in the Arctic and for supporting ecosystem-based management.

Within the EU, the Natura 2000 network of protected areas (related to the Bird and Habitat Directives) plays a key role for obliging member states to ensure that especially valuable sites are managed in a sustainable manner. However, neither Norway nor Greenland is part of this network, and any influence from the EU would thus be indirect, such as leading by example and setting norms. There is currently no legal framework for creating marine-protected areas beyond the EEZs. The ongoing work on marine-protected areas under the Convention for the Protection of the Marine Environment of the North-East Atlantic (OSPAR Convention) is relevant, however, as it focuses on protecting the marine environment from pollution and includes Arctic waters (OSPAR Region 1) that are beyond national jurisdictions.83 Another potential venue is the Arctic 5+5 collaboration that led to the Agreement to Prevent Unregulated High Seas Fisheries in the Central Arctic Ocean, to which the EU is a signatory. A stronger engagement of the EU in the Arctic Council Working Group for the Conservation of Arctic Flora and Fauna (CAFF) would strengthen the EU’s potential role in biodiversity governance in the Arctic Ocean.84

4.6 Climate change mitigation and adaptation

With its far-reaching impacts, the changing Arctic climate is likely to have major consequences for both the environment and for people living in the region. However, the drivers of this change – the anthropogenic emissions of gases and particles that affect the climate – are mainly global in scope. The EU’s space of policy action thus mainly relates to its role in climate mitigation, with a mix of policy influence in global policy areas, such as the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), and internal actions to promote a shift away from fossil fuels in energy and production systems.

In addition to its role in leading climate mitigation efforts, the EU plays a role in relation to adaptation.85 Its long-term vision is that in 2050, the EU will be a climate-resilient society, fully adapted to the unavoidable impacts of climate change. The strategy also includes a provision to help increase climate resilience globally, for example, by engaging in regional fisheries management organisations to promote adaptation and new marine-protected areas. It specifically states that the EU will “include climate change considerations in the future agreement on the conservation and sustainable use of marine biodiversity of areas beyond national jurisdiction,” which will also be relevant in the Arctic.86

5. Concluding discussion

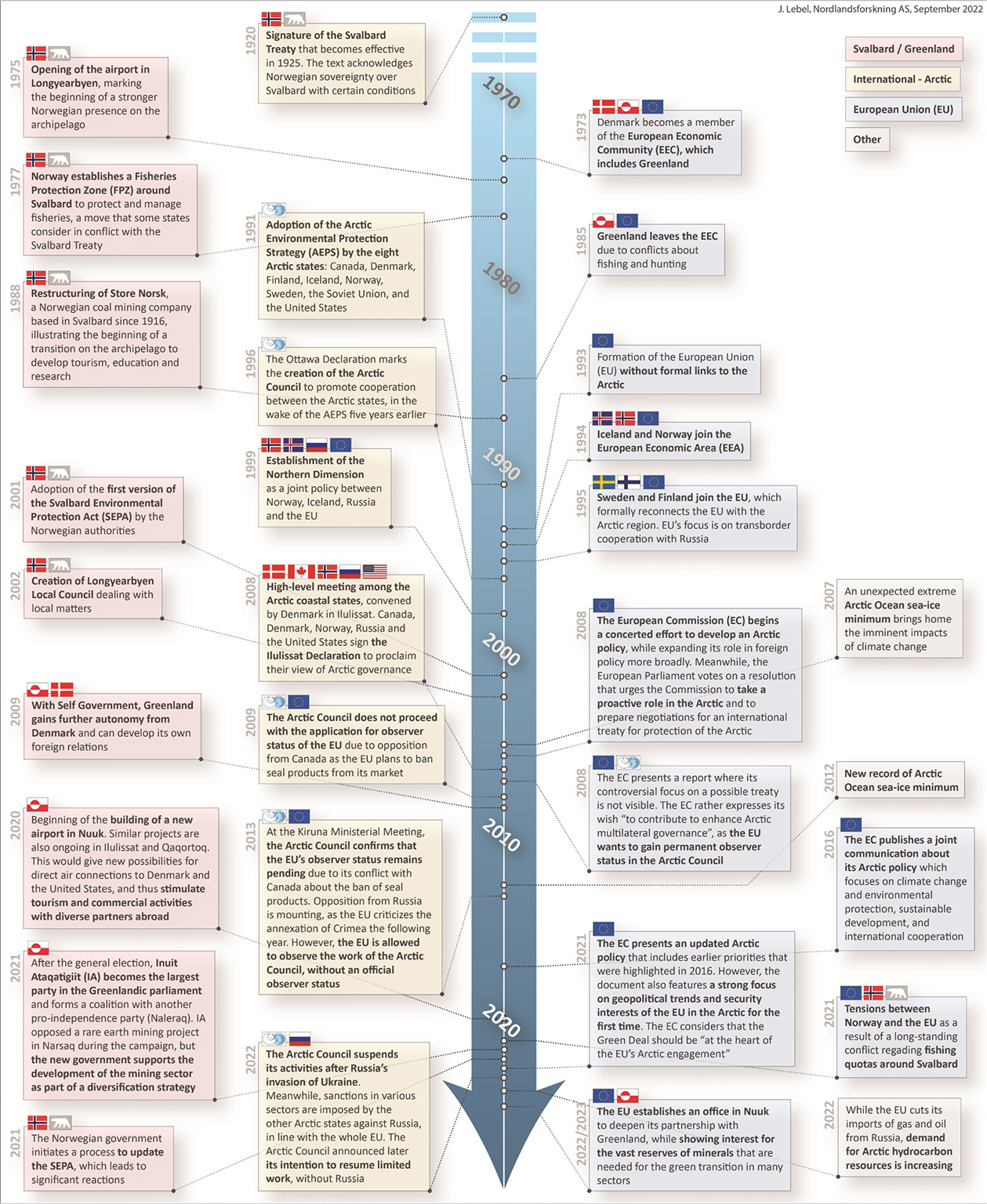

Over the past two decades, the Arctic has been characterised by dramatic environmental changes, followed by increasing political interest from Arctic states, as well as from external actors. Over time, the EU’s engagement in the Arctic has increased (figure 2), but its influence is circumscribed by its lack of formal jurisdiction. Its legitimacy as an Arctic actor is also challenged. However, it is also clear that the EU’s indirect influence, including its environmental footprint, is substantial due to environmental, economic, and policy-related teleconnections. Its financial contribution to Arctic research and related policy activities adds yet another dimension of influence. To some extent, one can argue that the EU’s Arctic policy may be less relevant than policies related to core political priorities, including the Green Deal, or to the economic interests of different member states. The fact that the EU’s role in the Arctic is often played through indirect processes rather than Arctic-specific policies also shows the importance of analyses based on the concept of telecoupling. Further analyses are needed to better understand how flows of money, material, people, knowledge and ideas between the EU and the Arctic affect specific localities across the Circumpolar North and their future.

Figure 2. Timeline of the EU’s engagement in the Arctic.

The language of the EU’s 2021 Arctic policy update suggests that geopolitical considerations and priorities connected with the Green Deal are likely to guide the EU’s Arctic engagement in the coming years. Moreover, the document’s assertive language describing the EU as a legitimate Arctic actor may suggest a willingness to use policy tools that do not meet with approval from Arctic states, including market and trade mechanisms. Even if the EU cannot determine specific environmental standards in key sectors, it can influence other stakeholders through international cooperation and by setting a trend with ambitious green policies.

Yet the EU’s ambitions are challenged by short-term issues linked to geopolitical uncertainty in the region, while the impacts of climate change are already affecting sea ice, glaciers, and biota in ways that are quickly changing the Arctic land- and seascapes. Changing environmental conditions not only put pressure on traditional livelihoods for local populations, but they also make it possible to access natural resources in new areas.

The strong integration of the Green Deal in the EU’s Arctic policy is, however, in contradiction with the interests of several European countries regarding extractive resources in the Circumpolar North. As Norway remains a major producer and exporter of oil and gas, these resources are significant to its economy. For Greenland, the extraction of rare earth minerals constitutes an opportunity to diversify its economy and gain further independence. In the meantime, many European countries must shift away from imports from Russia and meet the demand for metals needed for the green transition in several sectors. For the EU there is a significant risk of being perceived as a “self-serving” actor in the region, despite EU communications emphasising the need to develop cooperation and improve dialogue with Indigenous peoples.

Moreover, the assertive tone of the new EU Arctic policy and the recent expansion of the NATO military alliance in Northern Europe may harm ambitions to maintain the Arctic as a “peaceful” region. While implementing sanctions against Russia in line with the EU, Norway has so far managed to maintain some communication channels with its neighbour in terms of pursuing the agreement regarding cod stocks management. Yet, since February 2022, one can observe a shift away from cooperation aimed at mitigating climate change and strengthening local development, especially through the work of the Arctic Council, towards a political discourse with a stronger focus on military and defence activities through strategic alliances, such as the growing role of NATO and the deepening ties between Russia and China. This may increase tensions in the Circumpolar North and divide the Arctic in the longer term.

This context corroborates the strategy of the EU to strengthen its presence and become a geopolitical actor in the region, in addition to reinforcing the goals of peace, stability and prosperity, as defined in the EU’s 2021 Arctic policy. However, without more attention to conflicting political priorities among various Arctic actors as well as how different political goals within the EU affect the Arctic, future EU Arctic policies are likely to have less influence on the region’s future than sector-specific regulations that guide the behaviour of EU members by influencing global norms and global trends.

Acknowledgments

This work is part of the FACE-IT research project (The Future of Arctic Coastal Ecosystems – Identifying Transitions in fjord systems and adjacent coastal areas) that is funded by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the call: H2020-LC-CLA-2018-2019-2020 (Building a low-carbon, climate resilient future: climate action in support of the Paris Agreement), Grant number: 869154.

Bibliography

- Ackrén, Maria, and Uffe Jakobsen. “Greenland as a Self-Governing Sub-National Territory in International Relations: Past, Current and Future Perspectives.” Polar Record 51, no. 4 (2015): 404–412. https://doi.org/10.1017/S003224741400028X

- Ackrén, Maria, and Rasmus Leander Nielsen. The First Foreign and Security Policy Opinion Poll in Greenland. Ilisimatusarfik/University of Greenland and Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung, 2021, https://uni.gl/media/6762444/fp-survey-2021-ilisimatusarfik.pdf

- Agreement to Prevent Unregulated High Seas Fisheries in the Central Arctic Ocean, 2018, http://publications.europa.eu/resource/cellar/d7bf52b8-ec1c-11e9-9c4e-01aa75ed71a1.0001.02/DOC_1

- Andersson, Patrik. “The Arctic as a ‘Strategic’ and ‘Important’ Chinese Foreign Policy Interest: Exploring the Role of Labels and Hierarchies in China’s Arctic Discourses.” Journal of Current Chinese Affairs (2021): 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1177/18681026211018699

- Arctic Council. “Plastics in the Arctic. Back in Sight, Back in Mind.” Accessed November 17, 2023. https://arctic-council.org/en/explore/topics/ocean/plastics/

- Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme. Adaptation Actions for a Changing Arctic: Perspectives from the Barents Area. AMAP, 2017, https://www.amap.no/documents/doc/adaptation-actions-for-a-changing-arctic-perspectives-from-the-barents-area/1604

- Avango, Dag, Louwrens Hacquebord, Ypie Aalders, Hidde De Haas, Ulf Gustafsson, and Frigga Kruse. “Between Markets and Geo-Politics: Natural Resource Exploitation on Spitsbergen from 1600 to the Present Day.” Polar Record 47, no. 1 (2011): 29–39. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0032247410000069

- Berg, Roald. “From ‘Spitsbergen’ to ‘Svalbard’. Norwegianization in Norway and in the ‘Norwegian Sea’, 1820–1925.” Acta Borealia 30, no. 2 (2013): 154–173. https://doi.org/10.1080/08003831.2013.843322

- Bjørst, Lill R. “To Live Up to Our Name ‘Greenland’: Politics of Comparison in Greenland’s Green Transition.” Arctic Yearbook (2022). https://arcticyearbook.com/images/yearbook/2022/Scholarly-Papers/18A_AY2022_Bjrst.pdf

- Cavalieri, Sandra, Emily McGlynn, Susanah Stoessel, Franziska Stuke, Martin Bruckner, Christine Polzin, Timo Koivurova, Nikolas Sellheim, Adam Stępień, Kamrul Hossain, Sébastien Duyck, and Annika E. Nilsson. EU Arctic Footprint and Policy Assessment. Final Report. Ecologic Institute, 2010, http://arctic-footprint.eu/sites/default/files/AFPA_Final_Report.pdf

- Conde Pérez, Elena, and Zhaklin Valerieva Yaneva. “The European Arctic Policy in Progress.” Polar Science 10, no. 3 (2016): 441–449. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polar.2016.06.008

- Conservation of Arctic Flora and Fauna. Arctic Biodiversity Assessment 2013: Status and Trends in Arctic Biodiversity. CAFF, 2013, https://www.caff.is/assessment-series/233-arctic-biodiversity-assessment-2013/download

- Council of the European Union. Council Conclusions on Arctic Issues. Brussels, 2985th Foreign Affairs Council Meeting, 2009, http://www.consilium.europa.eu/uedocs/cms_Data/docs/pressdata/EN/foraff/111814.pdf

- Dawson, Jackie, Emma J. Stewart, Margaret E. Johnston, and Christopher J. Lemieux. “Identifying and Evaluating Adaptation Strategies for Cruise Tourism in Arctic Canada.” Journal of Sustainable Tourism 24, no. 10 (2016): 1425–1441. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2015.1125358

- Dodds, Klaus. “The Ilulissat Declaration (2008): The Arctic States, ‘Law of the Sea,’ and Arctic Ocean.” SAIS Review of International Affairs 33, no. 2 (2013): 45–55. https://doi.org/10.1353/sais.2013.0018

- Eritja, Mar Campins. “Strengthening the European Union-Greenland’s Relationship for Enhanced Governance of the Arctic.” In The European Union and the Arctic, edited by Nengye Liu, Elizabeth A. Kirk, and Tore Henriksen, 65–96. Brill, 2017. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1163/j.ctt1w8h3gv.9

- EU Polar Cluster, ECOTIP, FACE-IT and CHARTER. Arctic Biodiversity, Climate and Food Security. Policy Briefing. 2023, https://www.face-it-project.eu/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/FACE-IT_ECOTIP_CHARTER_PolicyBriefing_BrochureWeb.pdf

- European Commission. The European Union and the Arctic Region. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council, 2008, http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/ALL/?uri=CELEX:52008DC0763

- European Commission. Strategic Goals and Recommendations for the EU’s Maritime Transport Policy until 2018. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions, 2009, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/ALL/?uri=CELEX:52009DC0008

- European Commission. Regulation (EU) No 511/2014 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 April 2014 on Compliance Measures for Users from the Nagoya Protocol on Access to Genetic Resources and the Fair and Equitable Sharing of Benefits Arising from their Utilization in the Union. Official Journal of the European Union, 2014, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32014R0511

- European Commission. Forging a Climate-Resilient Europe – the New EU Strategy on Adaptation to Climate Change. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions, 2021, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=COM:2021:82:FIN

- European Commission. “Common Fisheries Policy (CFP).” Oceans and Fisheries. Accessed November 14, 2023. https://ec.europa.eu/oceans-and-fisheries/policy/common-fisheries-policy-cfp_en

- European Commission. “European Tourism Indicators System for Sustainable Destination Management.” Internal Market, Industry, Entrepreneurship and SMEs. Accessed November 15, 2023. https://ec.europa.eu/growth/sectors/tourism/offer/sustainable/indicators_en

- European Commission. “Greenland.” International Partnerships. Accessed December 12, 2023. https://international-partnerships.ec.europa.eu/countries/greenland_en

- European Commission and Directorate-General for Maritime Affairs and Fisheries. “EU Expresses Concern over Unsustainable Decisions on Arctic Cod by Norway and Russia.” Oceans and Fisheries, News Announcement. Accessed November 14, 2023. https://ec.europa.eu/oceans-and-fisheries/news/eu-expresses-concern-over-unsustainable-decisions-arctic-cod-norway-and-russia-2021-08-23_en

- European Commission, Directorate-General for Maritime Affairs and Fisheries and European External Action Service. Developing a European Union Policy towards the Arctic Region: Progress since 2008 and Next Steps. Joint Communication to the European Parliament and the Council, 2012, https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/70245d63-201c-47e8-9091-d5c07b96d964

- European Commission, Directorate-General for Maritime Affairs and Fisheries and European External Action Service. Summary of the Results of the Public Consultation on the EU Arctic Policy. EU publications, 2020, https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/497bfd35-5f8a-11eb-b487-01aa75ed71a1

- European Commission and European External Action Service. An Integrated European Union Policy for the Arctic. Joint Communication to the European Parliament and the Council, 2016, https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/4b591893-0d25-11e6-ba9a-01aa75ed71a1/language-en/format-PDF/source-297029460

- European Commission and European External Action Service. A Stronger EU Engagement for a Peaceful, Sustainable and Prosperous Arctic. Joint Communication to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions, 2021, https://eeas.europa.eu/headquarters/headquarters-homepage/105481/joint-communication-stronger-eu-engagement-peaceful-sustainable-and-prosperous-arctic_en

- European Environment Agency. “Status of Marine Fish and Shellfish Stocks in European Seas.” Analysis and data from the European Environment Agency. Accessed November 15, 2023. https://www.eea.europa.eu/data-and-maps/indicators/status-of-marine-fish-stocks-5/assessment

- Gad, Ulrik Pram. National Identity Politics and Postcolonial Sovereignty Games: Greenland, Denmark and the European Union. Museum Tusculanum Press, 2017.

- Goodenough, Kathryn M., J. Schilling, Erik Jonsson, Per Kalvig, Nicolas Charles, Johann Tuduri, Eimear A. Deady, Martiya Sadeghi, Henrik Schiellerup, Axel Müller, et al. “Europe’s Rare Earth Element Resource Potential: An Overview of REE Metallogenetic Provinces and Their Geodynamic Setting.” Ore Geology Reviews 72, no. 1 (2016): 838–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oregeorev.2015.09.019

- Graugaard, Naja Dyrendom. “Fornemmelse for sæl? Sælens’ flerhed’i Grønland, vestlige fortolkninger og EU’s sælregime fra Arktis.” Tidsskriftet Grønland 4 (2020): 166–182.

- Haugevik, Kristin. “Diplomacy through the Back Door: Norway and the Bilateral Route to EU Decision-Making.” Global Affairs 3, no. 3 (2017): 277–91. https://doi.org/10.1080/23340460.2017.1378586

- Heininen, Lassi, Karen Everett, Barbora Padrtova, and Anni Reissell. Arctic Policies and Strategies – Analysis, Synthesis, and Trends. International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis, 2020, http://dx.doi.org/10.22022/AFI/11-2019.16175

- Hermann, Roberto Rivas, Ning Lin, Julien Lebel, and Alina Kovalenko. “Arctic Transshipment Hub Planning along the Northern Sea Route: A Systematic Literature Review and Policy Implications of Arctic Port Infrastructure.” Marine Policy 145 (2022): 105275. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2022.105275

- Hull, Vanessa, and Jianguo Liu. “Telecoupling: A New Frontier for Global Sustainability.” Ecology and Society 23, no. 4 (2018): 41. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-10494-230441

- Ingimundarson, Valur. “Managing a Contested Region: The Arctic Council and the Politics of Arctic Governance.” The Polar Journal 4, no. 1 (2014): 183–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/2154896X.2014.913918

- International Maritime Organisation. International Code for Ships Operating in Polar Waters (Polar Code). Resolution MSC.385(94) adopted on 21 November 2014 by the Maritime Safety Committee, 2014, https://wwwcdn.imo.org/localresources/en/KnowledgeCentre/IndexofIMOResolutions/MSCResolutions/MSC.385(94).pdf

- Jonassen, Trine. “The AEC on the EU Arctic Policy: ‘Leave Arctic Business to the People Who Live Here.’” High North News, October 15, 2021. https://www.highnorthnews.com/en/aec-eu-arctic-policy-leave-arctic-business-people-who-live-here

- Kaltenborn, Bjørn P., Willy Østreng, and Grete K. Hovelsrud. “Change Will Be the Constant – Future Environmental Policy and Governance Challenges in Svalbard.” Polar Geography 43, no. 1 (2020): 25–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/1088937X.2019.1679269

- Kobzeva, Mariia. “China’s Arctic Policy: Present and Future.” The Polar Journal 9, no. 1 (2019): 94–112. https://doi.org/10.1080/2154896X.2019.1618558

- Koivurova, Timo, Alf Håkon Hoel, Malte Humpert, Stefan Kirchner, Andreas Raspotnik, Małgorzata Śmieszek, and Adam Stępień. Overview of EU Actions in the Arctic and Their Impact. EPDR Office for Economic Policy and Regional Development, 2021, https://eprd.pl/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/EU-Policy-Arctic-Impact-Overview-Final-Report.pdf

- Laruelle, Marlène. Russia’s Arctic Policy: A Power Strategy and Its Limits. Notes de l’IFRI, 117. Institut Français des Relations Internationales, 2020, https://www.ifri.org/en/publications/notes-de-lifri/russieneivisions/russias-arctic-policy-power-strategy-and-its-limits

- Lawlor, Niall, Gijs Nolet, Guillermo Hernandez, Paola Banfi, Mark Mackintosh, Michael Wenborn, Lars Lund Sørensen, Karen Hanghøj, Bo Møller Stensgaard, Per Kalvig, et al. Study on EU Needs with Regard to Co-Operation with Greenland. Milieu, 2015, https://ec.europa.eu/docsroom/documents/11724/attachments/1/translations/en/renditions/native

- Lemelin, Raynald Harvey, Emma J. Stewart, and Jackie Dawson. “An Introduction to Last Chance Tourism.” In Last Chance Tourism: Adapting Tourism Opportunities in a Changing World, edited by Raynald Harvey Lemelin, Jackie Dawson, and Emma J. Stewart, 21–27. Routledge, 2011. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203828939

- Liu, Nengye, and Elizabeth A. Kirk. “The European Union’s Potential Contribution to Protect Marine Biodiversity in the Changing Arctic: A Roadmap.” The International Journal of Marine and Coastal Law 30, no. 2 (2015): 255–284. https://doi.org/10.1163/15718085-12341354

- Nilsson, Annika E. “The United States and the making of an Arctic nation.” Polar Record 54, no. 2 (2018): 97–107. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0032247418000219

- Nilsson, Annika E., and Miyase Christensen. Arctic Geopolitics, Media and Power. Routledge, 2019. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429199646

- Norwegian Government. “Store Norske Spitsbergen Kulkompani forlenger produksjonen av industrikull til Europa fram til sommeren 2025.” Press release from the Norwegian Government. Accessed November 16, 2023. https://www.regjeringen.no/no/aktuelt/store-norske-spitsbergen-kulkompani-pa-svalbard-forlenger-produksjonen-av-industrikull-til-europa-fram-til-sommeren-2025/id2926294/?utm_source=regjeringen.no&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=nyhetsvarsel20220902

- Oberlack, Christoph, Sébastien Boillat, Stefan Brönnimann, Jean-David Gerber, Andreas Heinimann, Chinwe Ifejika Speranza, Peter Messerli, Stephan Rist, and Urs Wiesmann. “Polycentric Governance in Telecoupled Resource Systems.” Ecology and Society 23, no. 1 (2018): 16. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-09902-230116

- Offerdal, Kristine. “The EU in the Arctic: In Pursuit of Legitimacy and Influence.” International Journal 66, no. 4 (2010): 861–877. https://doi.org/10.1177/002070201106600414

- OSPAR. “MPAS in areas beyond national jurisdiction.” OSPAR Commission. Accessed November 14, 2023. https://www.ospar.org/work-areas/bdc/marine-protected-areas/mpas-in-areas-beyond-national-jurisdiction

- Østhagen, Andreas. “The European Union – An Arctic Actor?” Journal of Military and Strategic Studies 15, no. 2 (2013): 71–92. https://jmss.org/article/view/58096

- Østhagen, Andreas. “Norway’s Arctic Policy: Still High North, Low Tension?” The Polar Journal 11, no. 1 (2021): 75–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/2154896X.2021.1911043

- Østhagen, Andreas, and Andreas Raspotnik. “Partners or Rivals? Norway and the European Union in the High North.” In The European Union and the Arctic, edited by Nengye Liu, Elizabeth A. Kirk, and Tore Henriksen, 97–118. Brill, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004349179_006

- Østhagen, Andreas, and Andreas Raspotnik. “Crab! How a Dispute over Snow Crab Became a Diplomatic Headache between Norway and the EU.” Marine Policy 98 (2018): 58–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2018.09.007

- Protection of the Arctic Marine Environment. The Increase in Arctic Shipping 2013–2019. Arctic Shipping Status Report #1. PAME International Secretariat, 2020, https://www.pame.is/projects/arctic-marine-shipping/arctic-shipping-status-reports/723-arctic-shipping-report-1-the-increase-in-arctic-shipping-2013-2019-pdf-version/file

- Phillips, Leigh. “Arctic Council rejects EU’s observer application.” EU Observer, April 30, 2009. http://euobserver.com/environment/28043

- Raspotnik, Andreas. The European Union and the Geopolitics of the Arctic. Edward Elgar Publishing, 2018.

- Scott, Daniel, C. Michael Hall, and Stefan Gössling. “Global Tourism Vulnerability to Climate Change.” Annals of Tourism Research 77 (2019): 49–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2019.05.007

- Sellheim, Nikolas. “The Neglected Tradition? – The Genesis of the EU Seal Products Trade Ban and Commercial Sealing.” The Yearbook of Polar Law Online 5, no. 1 (2013): 417–450. https://doi.org/10.1163/22116427-91000132

- Sellheim, Nikolas. “The Goals of the EU Seal Products Trade Regulation: From Effectiveness to Consequence.” Polar Record 51, no. 3 (2015): 274–289. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0032247414000023

- Stępień, Adam, and Timo Koivurova. “Formulating a Cross-Cutting Policy: Challenges and Opportunities for Effective EU Arctic Policy-Making.” In The European Union and the Arctic, edited by Nengye Liu, Elizabeth A. Kirk, and Tore Henriksen, 9–39. Brill, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004349179_003

- Supreme Court of Norway. “The Svalbard Treaty does not give a Latvian shipping company the right to catch snow crab on the continental shelf outside Svalbard.” Rulings. Accessed November 6, 2023. https://www.domstol.no/en/supremecourt/rulings/2023/supreme-court-civil-cases/HR-2023-491-P/

- Traité Concernant Le Spitsberg, 1925, https://lovdata.no/dokument/TRAKTATEN/traktat/1920-02-09-1

- Turunen, Minna, Anna Degteva, Seija Tuulentie, Anatoli Bourmistrov, Robert Corell, Edward Dunlea, Grete K. Hovelsrud, Timo Jouttijärvi, Sari Kauppi, Nancy Maynard, et al. “Impact Analyses and Consequences of Change.” In Adaptation Actions for a Changing Arctic: Perspectives from the Barents Area, Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme, 127–166. AMAP, 2017. https://www.amap.no/documents/download/2981/inline

- Vanhoonacker, Sophie, and Karolina Pomorska. “The European External Action Service and Agenda-Setting in European Foreign Policy.” Journal of European Public Policy 20, no. 9 (2013): 1316–1331. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2012.758446

- Vylegzhanin, Alexander N., Oran R. Young, and Paul Arthur Berkman. “The Central Arctic Ocean Fisheries Agreement as an Element in the Evolving Arctic Ocean Governance Complex.” Marine Policy 118 (2020): 104001. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2020.104001

- Wegge, Njord. “The EU and the Arctic: European Foreign Policy in the Making.” Arctic Review on Law and Politics 3, no. 1 (2012): 6–29. https://www.jstor.org/stable/48710161

Footnotes

- 1 European Commission and European External Action Service, A Stronger EU Engagement for a Peaceful, Sustainable and Prosperous Arctic, Joint Communication to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions, 2021, https://eeas.europa.eu/headquarters/headquarters-homepage/105481/joint-communication-stronger-eu-engagement-peaceful-sustainable-and-prosperous-arctic_en

- 2 Kristine Offerdal, “The EU in the Arctic: In Pursuit of Legitimacy and Influence,” International Journal 66, no. 4 (2010): 861–877, https://doi.org/10.1177/002070201106600414; Njord Wegge, “The EU and the Arctic: European Foreign Policy in the Making.” Arctic Review on Law and Politics 3, no. 1 (2012): 6–29, https://www.jstor.org/stable/48710161

- 3 Sophie Vanhoonacker and Karolina Pomorska, “The European External Action Service and Agenda-Setting in European Foreign Policy,” Journal of European Public Policy 20, no. 9 (2013): 1316–1331, https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2012.758446

- 4 Christoph Oberlack et al., “Polycentric Governance in Telecoupled Resource Systems,” Ecology and Society 23, no. 1 (2018): 16, https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-09902-230116

- 5 Vanessa Hull and Jianguo Liu, “Telecoupling: A New Frontier for Global Sustainability,” Ecology and Society 23, no. 4 (2018): 41, https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-10494-230441

- 6 Lassi Heininen et al., Arctic Policies and Strategies – Analysis, Synthesis, and Trends, International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis, 2020, http://dx.doi.org/10.22022/AFI/11-2019.16175

- 7 Elena Conde Pérez and Zhaklin Valerieva Yaneva, “The European Arctic Policy in Progress,” Polar Science 10, no. 3 (2016): 441–449, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polar.2016.06.008; Andreas Raspotnik, The European Union and the Geopolitics of the Arctic (Edward Elgar Publishing, 2018); Adam Stępień and Timo Koivurova, “Formulating a Cross-Cutting Policy: Challenges and Opportunities for Effective EU Arctic Policy-Making,” in The European Union and the Arctic, ed. Nengye Liu, Elizabeth A. Kirk and Tore Henriksen (Brill, 2017), 9–39, https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004349179_003

- 8 Annika E. Nilsson, “The United States and the making of an Arctic nation,” Polar Record 54, no. 2 (2018): 97–107, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0032247418000219

- 9 Marlène Laruelle, Russia’s Arctic Policy: A Power Strategy and Its Limits. Notes de l’IFRI, 117, Institut Français des Relations Internationales, 2020, https://www.ifri.org/en/publications/notes-de-lifri/russieneivisions/russias-arctic-policy-power-strategy-and-its-limits

- 10 Mariia Kobzeva, “China’s Arctic Policy: Present and Future,” The Polar Journal 9, no. 1 (2019): 94–112, https://doi.org/10.1080/2154896X.2019.1618558

- 11 European Commission and European External Action Service, A Stronger EU Engagement for a Peaceful, Sustainable and Prosperous Arctic.

- 12 EU Polar Cluster, ECOTIP, FACE-IT and CHARTER, Arctic Biodiversity, Climate and Food Security. Policy Briefing, 2023, https://www.face-it-project.eu/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/FACE-IT_ECOTIP_CHARTER_PolicyBriefing_BrochureWeb.pdf

- 13 Annika E. Nilsson and Miyase Christensen, Arctic Geopolitics, Media and Power (Routledge, 2019), https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429199646

- 14 Offerdal, “The EU in the Arctic: In Pursuit of Legitimacy and Influence”; Wegge, “The EU and the Arctic: European Foreign Policy in the Making.”

- 15 Klaus Dodds, “The Ilulissat Declaration (2008): The Arctic States, “Law of the Sea,” and Arctic Ocean,” SAIS Review of International Affairs 33, no. 2 (2013): 45–55, https://doi.org/10.1353/sais.2013.0018; Wegge, “The EU and the Arctic: European Foreign Policy in the Making.”

- 16 European Commission, The European Union and the Arctic Region, Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council, 2008, http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/ALL/?uri=CELEX:52008DC0763; Wegge, “The EU and the Arctic: European Foreign Policy in the Making.”

- 17 Valur Ingimundarson, “Managing a Contested Region: The Arctic Council and the Politics of Arctic Governance,” The Polar Journal 4, no. 1 (2014): 183–98, https://doi.org/10.1080/2154896X.2014.913918; Leigh Phillips, “Arctic Council rejects EU’s observer application,” EU Observer, April 30, 2009, http://euobserver.com/environment/28043; Wegge, “The EU and the Arctic: European Foreign Policy in the Making.”

- 18 Offerdal, “The EU in the Arctic: In Pursuit of Legitimacy and Influence.”

- 19 Council of the European Union, Council Conclusions on Arctic Issues, Brussels, 2985th Foreign Affairs Council Meeting, 2009, http://www.consilium.europa.eu/uedocs/cms_Data/docs/pressdata/EN/foraff/111814.pdf; European Commission, Directorate-General for Maritime Affairs and Fisheries and European External Action Service, Developing a European Union Policy towards the Arctic Region: Progress since 2008 and Next Steps, Joint Communication to the European Parliament and the Council, 2012, https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/70245d63-201c-47e8-9091-d5c07b96d964; European Commission and European External Action Service, An Integrated European Union Policy for the Arctic, Joint Communication to the European Parliament and the Council, 2016, https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/4b591893-0d25-11e6-ba9a-01aa75ed71a1/language-en/format-PDF/source-297029460

- 20 European Commission, Directorate-General for Maritime Affairs and Fisheries and European External Action Service, Summary of the Results of the Public Consultation on the EU Arctic Policy, EU publications, 2020, https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/497bfd35-5f8a-11eb-b487-01aa75ed71a1

- 21 European Commission and European External Action Service, A Stronger EU Engagement for a Peaceful, Sustainable and Prosperous Arctic.

- 22 Lill R. Bjørst, “To Live Up to Our Name “Greenland”: Politics of Comparison in Greenland’s Green Transition,” Arctic Yearbook (2022), https://arcticyearbook.com/images/yearbook/2022/Scholarly-Papers/18A_AY2022_Bjrst.pdf

- 23 European Commission and European External Action Service, A Stronger EU Engagement for a Peaceful, Sustainable and Prosperous Arctic.

- 24 Trine Jonassen, “The AEC on the EU Arctic Policy: ‘Leave Arctic Business to the People Who Live Here,’” High North News, October 15, 2021, https://www.highnorthnews.com/en/aec-eu-arctic-policy-leave-arctic-business-people-who-live-here

- 25 Ulrik Pram Gad, National Identity Politics and Postcolonial Sovereignty Games: Greenland, Denmark and the European Union (Museum Tusculanum Press, 2017).

- 26 Maria Ackrén and Uffe Jakobsen, “Greenland as a Self-Governing Sub-National Territory in International Relations: Past, Current and Future Perspectives,” Polar Record 51, no. 4 (2015): 404–412, https://doi.org/10.1017/S003224741400028X

- 27 European Commission, “Greenland,” International Partnerships, accessed December 12, 2023, https://international-partnerships.ec.europa.eu/countries/greenland_en

- 28 European Commission and European External Action Service, A Stronger EU Engagement for a Peaceful, Sustainable and Prosperous Arctic.

- 29 Maria Ackrén and Rasmus Leander Nielsen, The First Foreign and Security Policy Opinion Poll in Greenland, Ilisimatusarfik/University of Greenland and Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung, 2021, https://uni.gl/media/6762444/fp-survey-2021-ilisimatusarfik.pdf

- 30 Naja Dyrendom Graugaard, “Fornemmelse for sæl? Sælens’ flerhed’i Grønland, vestlige fortolkninger og EU’s sælregime fra Arktis,” Tidsskriftet Grønland 4 (2020): 166–182.

- 31 Andreas Østhagen, “The European Union – An Arctic Actor?” Journal of Military and Strategic Studies 15, no. 2 (2013): 71–92, https://jmss.org/article/view/58096; Phillips, “Arctic Council rejects EU’s observer application”; Nikolas Sellheim, “The Neglected Tradition? – The Genesis of the EU Seal Products Trade Ban and Commercial Sealing,” The Yearbook of Polar Law Online 5, no. 1 (2013): 417–450, https://doi.org/10.1163/22116427-91000132; Nikolas Sellheim, “The Goals of the EU Seal Products Trade Regulation: From Effectiveness to Consequence,” Polar Record 51, no. 3 (2015): 274–289, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0032247414000023

- 32 Goodenough et al., “Europe’s Rare Earth Element Resource Potential: An Overview of REE Metallogenetic Provinces and Their Geodynamic Setting,” Ore Geology Reviews 72, no. 1 (2016): 838–56, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oregeorev.2015.09.019; Niall Lawlor et al., Study on EU Needs with Regard to Co-Operation with Greenland, Milieu, 2015, https://ec.europa.eu/docsroom/documents/11724/attachments/1/translations/en/renditions/native

- 33 Patrik Andersson, “The Arctic as a ‘Strategic’ and ‘Important’ Chinese Foreign Policy Interest: Exploring the Role of Labels and Hierarchies in China’s Arctic Discourses,” Journal of Current Chinese Affairs (2021): 1–27, https://doi.org/10.1177/18681026211018699

- 34 Mar Campins Eritja, “Strengthening the European Union-Greenland’s Relationship for Enhanced Governance of the Arctic,” in The European Union and the Arctic, ed. Nengye Liu, Elizabeth A. Kirk and Tore Henriksen (Brill, 2017), 65–96, http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1163/j.ctt1w8h3gv.9

- 35 Andreas Østhagen and Andreas Raspotnik, “Partners or Rivals? Norway and the European Union in the High North,” in The European Union and the Arctic, ed. Nengye Liu, Elizabeth A. Kirk and Tore Henriksen (Brill, 2017), 97–118, https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004349179_006

- 36 Ibid.

- 37 Kristin Haugevik, “Diplomacy through the Back Door: Norway and the Bilateral Route to EU Decision-Making,” Global Affairs 3, no. 3 (2017): 277–91, https://doi.org/10.1080/23340460.2017.1378586

- 38 Ibid.

- 39 Traité Concernant Le Spitsberg, 1925, https://lovdata.no/dokument/TRAKTATEN/traktat/1920-02-09-1

- 40 Dag Avango et al., “Between Markets and Geo-Politics: Natural Resource Exploitation on Spitsbergen from 1600 to the Present Day,” Polar Record 47, no. 1 (2011): 29–39, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0032247410000069; Roald Berg, “From “Spitsbergen” to “Svalbard”. Norwegianization in Norway and in the “Norwegian Sea”, 1820–1925,” Acta Borealia 30, no. 2 (2013): 154–173, https://doi.org/10.1080/08003831.2013.843322

- 41 Andreas Østhagen, “Norway’s Arctic Policy: Still High North, Low Tension?” The Polar Journal 11, no. 1 (2021): 75–94, https://doi.org/10.1080/2154896X.2021.1911043

- 42 Andreas Østhagen and Andreas Raspotnik, “Crab! How a Dispute over Snow Crab Became a Diplomatic Headache between Norway and the EU,” Marine Policy 98 (2018): 58–64, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2018.09.007

- 43 Ibid.

- 44 Supreme Court of Norway, “The Svalbard Treaty does not give a Latvian shipping company the right to catch snow crab on the continental shelf outside Svalbard,” Rulings, accessed November 6, 2023, https://www.domstol.no/en/supremecourt/rulings/2023/supreme-court-civil-cases/HR-2023-491-P/

- 45 European Commission and Directorate-General for Maritime Affairs and Fisheries, “EU Expresses Concern over Unsustainable Decisions on Arctic Cod by Norway and Russia,” Oceans and Fisheries, News Announcement, accessed November 14, 2023, https://ec.europa.eu/oceans-and-fisheries/news/eu-expresses-concern-over-unsustainable-decisions-arctic-cod-norway-and-russia-2021-08-23_en

- 46 Bjørn P. Kaltenborn et al., “Change Will Be the Constant – Future Environmental Policy and Governance Challenges in Svalbard,” Polar Geography 43, no. 1 (2020): 25–45, https://doi.org/10.1080/1088937X.2019.1679269

- 47 Ibid.

- 48 Timo Koivurova et al., Overview of EU Actions in the Arctic and Their Impact, EPDR Office for Economic Policy and Regional Development, 2021, https://eprd.pl/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/EU-Policy-Arctic-Impact-Overview-Final-Report.pdf

- 49 Østhagen, “The European Union – An Arctic Actor?”

- 50 Sandra Cavalieri et al., EU Arctic Footprint and Policy Assessment. Final Report, Ecologic Institute, 2010, http://arctic-footprint.eu/sites/default/files/AFPA_Final_Report.pdf

- 51 European Environment Agency, “Status of Marine Fish and Shellfish Stocks in European Seas,” Analysis and data from the European Environment Agency, accessed November 15, 2023, https://www.eea.europa.eu/data-and-maps/indicators/status-of-marine-fish-stocks-5/assessment

- 52 European Commission and Directorate-General for Maritime Affairs and Fisheries, “EU Expresses Concern over Unsustainable Decisions on Arctic Cod by Norway and Russia.”

- 53 Arctic Council, “Plastics in the Arctic. Back in Sight, Back in Mind,” accessed November 17, 2023, https://arctic-council.org/en/explore/topics/ocean/plastics/

- 54 Koivurova et al., Overview of EU Actions in the Arctic and Their Impact.

- 55 Conservation of Arctic Flora and Fauna, Arctic Biodiversity Assessment 2013: Status and Trends in Arctic Biodiversity, CAFF, 2013, https://www.caff.is/assessment-series/233-arctic-biodiversity-assessment-2013/download

- 56 Agreement to Prevent Unregulated High Seas Fisheries in the Central Arctic Ocean, 2018, http://publications.europa.eu/resource/cellar/d7bf52b8-ec1c-11e9-9c4e-01aa75ed71a1.0001.02/DOC_1

- 57 Alexander N. Vylegzhanin et al., “The Central Arctic Ocean Fisheries Agreement as an Element in the Evolving Arctic Ocean Governance Complex,” Marine Policy 118 (2020): 104001, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2020.104001

- 58 European Commission, “Common Fisheries Policy (CFP),” Oceans and Fisheries, accessed November 14, 2023, https://ec.europa.eu/oceans-and-fisheries/policy/common-fisheries-policy-cfp_en

- 59 Nengye Liu and Elizabeth A. Kirk, “The European Union’s Potential Contribution to Protect Marine Biodiversity in the Changing Arctic: A Roadmap,” The International Journal of Marine and Coastal Law 30, no. 2 (2015): 255–284, https://doi.org/10.1163/15718085-12341354

- 60 Minna Turunen et al., “Impact Analyses and Consequences of Change,” in Adaptation Actions for a Changing Arctic: Perspectives from the Barents Area, Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme (AMAP, 2017), 127–166, https://www.amap.no/documents/download/2981/inline

- 61 Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme, Adaptation Actions for a Changing Arctic: Perspectives from the Barents Area, AMAP, 2017, https://www.amap.no/documents/doc/adaptation-actions-for-a-changing-arctic-perspectives-from-the-barents-area/1604; Raynald Harvey Lemelin et al., “An Introduction to Last Chance Tourism,” in Last Chance Tourism: Adapting Tourism Opportunities in a Changing World, ed. Raynald Harvey Lemelin, Jackie Dawson and Emma J. Stewart (Routledge, 2011), 21–27, https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203828939

- 62 Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme, Adaptation Actions for a Changing Arctic: Perspectives from the Barents Area.

- 63 Jackie Dawson et al., “Identifying and Evaluating Adaptation Strategies for Cruise Tourism in Arctic Canada,” Journal of Sustainable Tourism 24, no. 10 (2016): 1425–1441, https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2015.1125358

- 64 Daniel Scott et al., “Global Tourism Vulnerability to Climate Change,” Annals of Tourism Research 77 (2019): 49–61, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2019.05.007

- 65 Koivurova et al., Overview of EU Actions in the Arctic and Their Impact.

- 66 European Commission, “European Tourism Indicators System for Sustainable Destination Management,” Internal Market, Industry, Entrepreneurship and SMEs, accessed November 15, 2023, https://ec.europa.eu/growth/sectors/tourism/offer/sustainable/indicators_en

- 67 Protection of the Arctic Marine Environment, The Increase in Arctic Shipping 2013–2019. Arctic Shipping Status Report #1, PAME International Secretariat, 2020, https://www.pame.is/projects/arctic-marine-shipping/arctic-shipping-status-reports/723-arctic-shipping-report-1-the-increase-in-arctic-shipping-2013-2019-pdf-version/file

- 68 Roberto Rivas Hermann et al., “Arctic Transshipment Hub Planning along the Northern Sea Route: A Systematic Literature Review and Policy Implications of Arctic Port Infrastructure,” Marine Policy 145 (2022): 105275, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2022.105275

- 69 Østhagen, “The European Union – An Arctic Actor?”

- 70 European Commission, Strategic Goals and Recommendations for the EU’s Maritime Transport Policy until 2018, Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions, 2009, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/ALL/?uri=CELEX:52009DC0008

- 71 European Commission and European External Action Service, A Stronger EU Engagement for a Peaceful, Sustainable and Prosperous Arctic.

- 72 International Maritime Organisation, International Code for Ships Operating in Polar Waters (Polar Code), Resolution MSC.385(94) adopted on 21 November 2014 by the Maritime Safety Committee, 2014, https://wwwcdn.imo.org/localresources/en/KnowledgeCentre/IndexofIMOResolutions/MSCResolutions/MSC.385(94).pdf

- 73 Liu and Kirk, “The European Union’s Potential Contribution to Protect Marine Biodiversity in the Changing Arctic: A Roadmap.”

- 74 Koivurova et al., Overview of EU Actions in the Arctic and Their Impact.

- 75 Ibid.

- 76 Liu and Kirk, “The European Union’s Potential Contribution to Protect Marine Biodiversity in the Changing Arctic: A Roadmap.”

- 77 Norwegian Government, “Store Norske Spitsbergen Kulkompani forlenger produksjonen av industrikull til Europa fram til sommeren 2025,” Press release from the Norwegian Government, accessed November 16, 2023, https://www.regjeringen.no/no/aktuelt/store-norske-spitsbergen-kulkompani-pa-svalbard-forlenger-produksjonen-av-industrikull-til-europa-fram-til-sommeren-2025/id2926294/?utm_source=regjeringen.no&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=nyhetsvarsel20220902%22

- 78 Koivurova et al., Overview of EU Actions in the Arctic and Their Impact.

- 79 Conservation of Arctic Flora and Fauna, Arctic Biodiversity Assessment 2013: Status and Trends in Arctic Biodiversity.

- 80 European Commission, Regulation (EU) No 511/2014 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 April 2014 on Compliance Measures for Users from the Nagoya Protocol on Access to Genetic Resources and the Fair and Equitable Sharing of Benefits Arising from their Utilization in the Union, Official Journal of the European Union, 2014, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32014R0511

- 81 Liu and Kirk, “The European Union’s Potential Contribution to Protect Marine Biodiversity in the Changing Arctic: A Roadmap.”

- 82 Ibid.

- 83 OSPAR, “MPAS in areas beyond national jurisdiction,” OSPAR Commission, accessed November 14, 2023, https://www.ospar.org/work-areas/bdc/marine-protected-areas/mpas-in-areas-beyond-national-jurisdiction

- 84 Koivurova et al., Overview of EU Actions in the Arctic and Their Impact.

- 85 European Commission, Forging a Climate-Resilient Europe – the New EU Strategy on Adaptation to Climate Change, Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions, 2021, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=COM:2021:82:FIN

- 86 Ibid.