1. Introduction

A key driver of economic development in the Arctic is the growing importance of the extractive industries, which has been augmented by the green and digital transitions. The northern part of Finland, and the Fennoscandian region more generally, possesses abundant mineral resources, making it an attractive destination for mining companies.1 While using this opportunity, the mining industry has experienced simultaneous growth and increasing opposition. New groups have emerged to resist specific mining projects2 or activities in certain regions.3

Over the course of 2022 and 2023, several mining-related legal reforms have been carried out to respond to the concerns of local people. The objective of the Mining Act in Finland was to raise the level of environmental protection, ensure the operating conditions of mines, and improve local acceptability and influencing opportunities.4 In addition, the Act on a Mined Minerals Tax, the new Nature Conservation Act, and the Environmental Damage Fund have been adopted. Moreover, the government proposed the amendment of the Act on the Sámi Parliament (974/1995). All these reforms are relevant to mining operations in the Arctic region of Finland. In this paper, we assess the extent to which the justice concerns of local stakeholders concerning distributive, procedural, recognition and intergenerational justice are reflected in these legal reforms.

This paper is structured as follows. Section 2 provides information about the research site, including its geographical location, demographics, history, and characteristics that may have influenced the study. Section 3 delves into the research setting, outlining the research design, methodology, and data collection procedures employed in the study. Section 4 describes the results derived from the empirical inquiry, while Section 5 scrutinizes the legal reforms, independent of the empirical analysis, in order to understand which substantial changes of the legal reforms are relevant from the perspectives of distributive, procedural, recognition justice and intergenerational justice. Finally, in Section 6, we discuss whether and to what extent these legal changes reflect the justice concerns of stakeholders. In this part of the paper, we combine the results of the analyses of the empirical material and legal changes. Finally, Section 7 encapsulates the key conclusions derived from the research endeavour.

2. Background

2.1. Social environment In Lapland and Sodankylä

Lapland is located in the northernmost region of Finland,5 where the population has declined continuously over the last 30 years from 200,000 in 1990 to 176,000 in 2021.6 Lapland is a sparsely populated area with a significant number of remote communities. The three most prominent employers in the region are health and social services (21.5%), industry (9.7%), and retail (9.4%).7 Mining and quarrying employed 2.6% of Lapland’s workforce in 2020.8

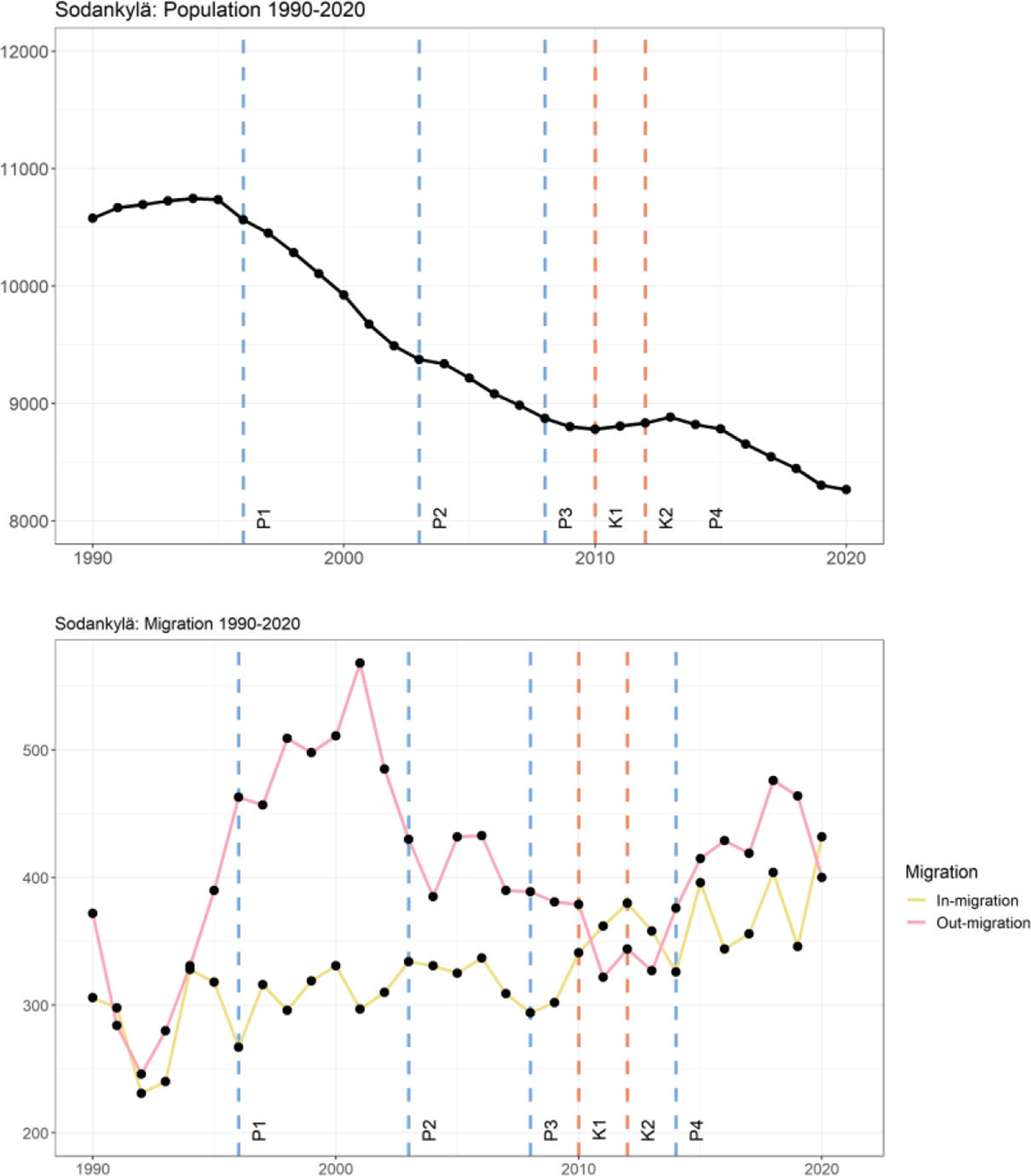

Sodankylä is a municipality of 8,134 inhabitants located in central Lapland.9 The municipality’s population has been declining since the mid-1990s. During this time, two large mining projects, Kevitsa and Pahtavaara, were developed in the area. While these mines most likely stalled the population decline, the process has steadily continued. There has been considerable in-migration before the start of construction and operation of the Kevitsa mine and an increase in out-migration after the end of the construction phase.10 Although establishing a causal relationship is challenging, there are changes in the migration patterns coinciding with the advancement of mining projects throughout their life cycles.

In addition to several exploration projects with few employees, three mining companies have a large number of employees. Boliden Kevitsa Mining Ltd. operates the Kevitsa mine in Sodankylä, employing 575 persons directly.11 Rupert Resources Ltd. owns the Pahtavaara mine estate and is conducting minerals exploration in the area employing 27 persons.12 AA Sakatti Mining Ltd. operating the Sakatti mining project is a subsidiary of Agnico Eagle Ltd. and employs 45 people.13

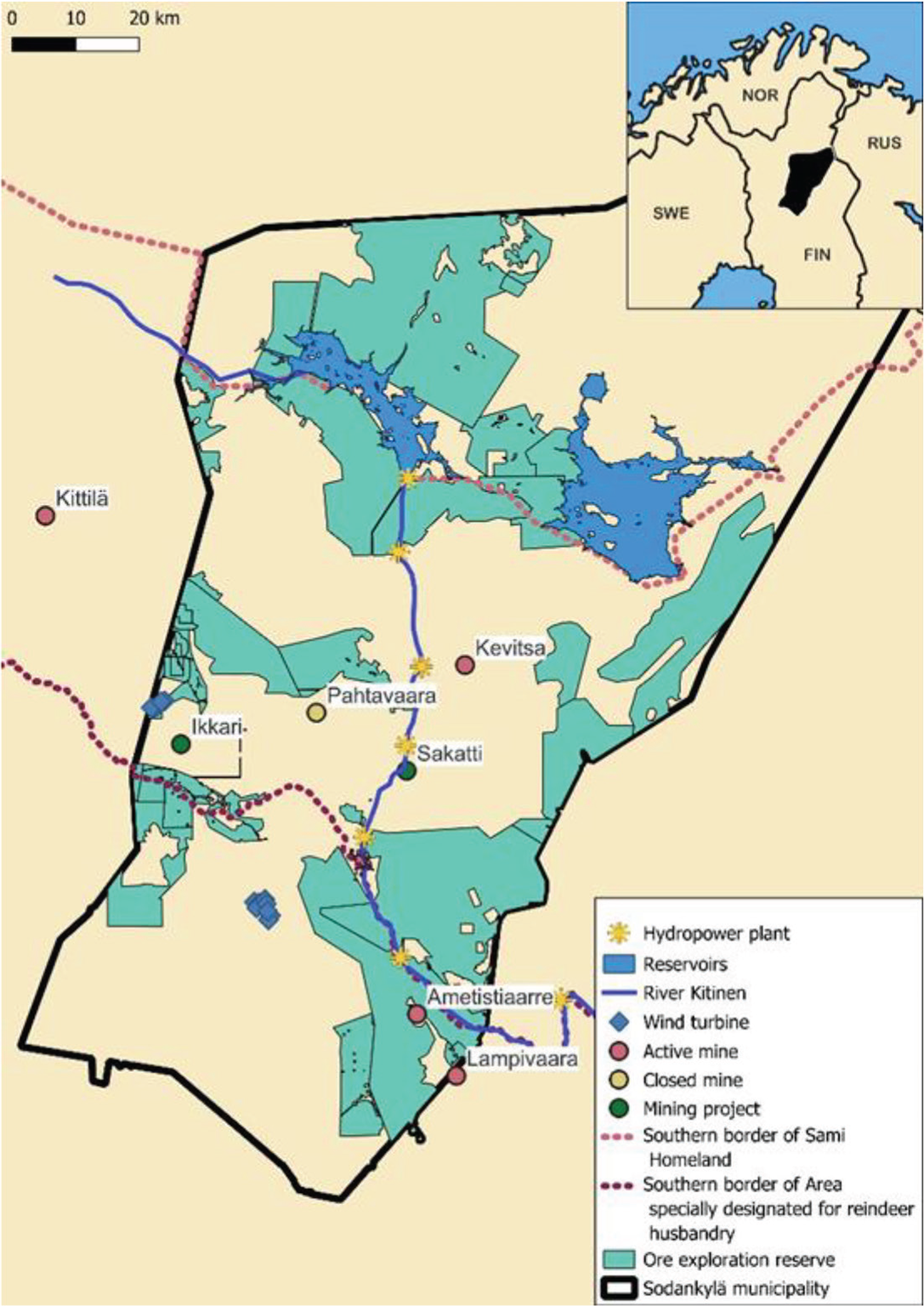

Sodankylä municipality is located in the reindeer herding area and home to five reindeer herding districts.14 Three of them belong to the area specifically designated for reindeer husbandry, where reindeer herding enjoys stricter protection than elsewhere in the reindeer herding area in accordance with the Reindeer Husbandry Act (848/1990). One of these three reindeer herding districts is located in the Sámi Homeland, where the Sámi as an indigenous people, have autonomy over their own language and culture, as specified in the Sámi Parliament Act.

During the rapid post-WW2 industrialization of Finland, the Sodankylä region was one of the main stages of hydropower development in Finland. Two reservoirs (Porttipahta and Lokka) were built at the end of the 1960s. In addition, there has been continuous discussion over a third reservoir called Vuotos since the 1950s,15 and it still appears frequently in the public debate in Lapland. Hydropower development involves major land-use projects which affect the mental landscape of the communities in the region. This heritage and its effects are an essential part of the social context of the area, as they belong to the background through which justice issues are often discussed.

2.2. Mining projects in Finnish Lapland

Modern industrial metallic ore mining in Finnish Lapland began in the early 20th century when the Petsamo ore deposit was discovered in the north-easternmost corner of Finland. Some years earlier, a significant metallic ore deposit was found in Outokumpu in eastern Finland. These discoveries heralded a new era in the Finnish mining industry.16 However, after the Second World War, the Petsamo region, including the mine, was ceded to the Soviet Union.

Between the 1950s and 1990s, the mining industry in Finland was dominated by national and mainly state-owned companies.17 During this period, a couple of mines started operation in Lapland—with the Kemi mine, still in operation, being the most successful.18 In addition, the iron mines of Hannukainen and Rautavaara in Kolari were operational during the 1970s and 1980s, and the Pahtavaara gold mine in Sodankylä between the 1980s and 2010s.

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, the mining industry was generally declining in Finland. The situation started to change during the late 1990s, when international mining companies were allowed to apply for mineral rights after Finland joined the EU in 1995. International mining companies had access to financial resources and hence were able to respond to the increasing global demand for minerals. While there are also national mining companies operating in Lapland, international companies currently dominate the mining industry.

There are currently three active mines in Finnish Lapland: Kemi (Cr), Kevitsa (Ni, Cu, Co, Pt, Pd, Au), and Suurkuusikko (Au, Ag).19 In addition, several mining projects are at the pre-mining stage, and a number of new mines could be opened during next decade. There are also thirteen closed mines in Lapland. Some of them might be re-opened, but most of them are relatively small.

In summary, the mining industry in Lapland is currently in a phase of expansion, where the desire for benefits and the fear of burdens are high. Some mines are already in operation, which has created jobs and produced other benefits for the local economy, but most mining projects are in the exploration or prospecting stage. No severe environmental accidents have occurred in Lapland. The economic benefits provided by mining tend to create a mood of optimism, which is advanced by a not-so-promising economic outlook in other sectors. An air of optimism is assumed to prevail in Sodankylä, which has one large mine in operation and several projects in the stage of prospecting and exploration. In Sodankylä municipality, the Kevitsa mine is the largest open-pit mine in Finland. In addition, the Sakatti and Ikkari mines are promising new mining projects, and re-opening the Pahtavaara mine seems likely. Not surprisingly, according to a study conducted in 2017,20 residents in Sodankylä generally considered mining to have a positive effect on the municipality. However, the respondents perceived a mismatch between the economic benefits of mining and the related environmental hazards. A follow-up study conducted in 202121 showed that while the general perception of mining was still positive, there were more critical views towards mining, as expectations about the benefits had not been fulfilled.

3. Research setting

3.1. Research question

Our research question is: ”Do the recent reforms of Finnish mining-related legislation reflect the justice concerns expressed by local residents?”. Our approach to this question includes two lines of inquiry: (1) an empirical analysis of local people’s justice concerns collected through fieldwork, and (2) an analysis of the extent to which the current legal reforms reflect the identified justice concerns. Hence, we aim to assess whether the ongoing legal reforms address local people’s justice concerns.

The assessment is based on the results of a qualitative analysis of data collected through interviews and a workshop. We identified key justice concerns expressed by the interviewees and participants in the workshop. Finally, we construed the concerns as ‘justice claims’ to use them as reference points in assessing the legal reforms. The justice claims are expressed straightforwardly as follows: “It is unjust that …”. We describe and discuss these results in Section 4, and then proceed to compare the justice claims with the legal reforms.

3.2. Key concepts

‘Forms of justice’22 are conceptual tools for dissecting the concept of justice in terms of the social organization of societies. They offer different perspectives on ‘justice’. However, forms of justice are not theories of justice per se, nor do they provide normative statements of justness. Theories of justice provide approaches and normative perspectives on justice. These theories range from canonical works on ethics and justice, such as liberal theories of justice,23 and cosmopolitan theories of justice,24 to applied theories of justice, such as climate justice25 and intergenerational justice.26 Our empirical analysis revealed that three forms of justice—distributive, procedural, and recognition justice—are particularly relevant for local people in the mining context. These forms of justice are complemented with a perspective drawn from the theory of intergenerational justice.

Distributive justice is a form of justice focused on the justness of distributing or allocating benefits and burdens across society.27 Distributive justice is closely tied to society’s social organization (law, policies, governance), as different ways of organization lead to different forms of distribution. In practice, distributive justice involves issues such as resources, harms, and power allocations.

Procedural justice, as a legal concept, is commonly understood as a form of law or practice that is to be applied equally to all. It is also understood as being connected to decision-making or judicial processes. This speaks to an understanding of the justness of the procedures used to determine how benefits and burdens are allocated to people. More pragmatically, procedural justice is manifested through ideas such as equal treatment and fair rules.

Recognition justice concerns the subject of justice: Who is recognized as eligible for making claims of justice? However, recognition justice is not only about participation, but also about fair representation, equal rights, and the recognition of differences.28 This form of justice is relational in that “Recognition is not a resource that can simply be distributed, but arises from the interaction of people who recognize each other—or between institutions and people”.29 Recognition justice is conceptually tied to distributive justice, as it developed mainly from a critique of distributive justice.30 This form of justice aims to understand “who is made invisible and whose impacts are not acknowledged”.31

Typically, justice issues are studied in the context of present generations.32 When looking at long-term development projects, such as mining projects, a focus on current generations narrows the scope of justice in a way that can leave most of the life cycle of a mining project out of the study. The intergenerational justice aspect of mining projects is also relevant because the legitimacy and social acceptance of these projects are related to expectations concerning the benefits, harms, and risks of the projects.33 Intergenerational justice as a theory is based on the idea that the relations of justice questions should be between past, present, and future generations.34 From an empirical perspective, this concept extends the timeframe of a justice assessment to past generations, current generations, and future generations. In essence, justice issues are understood in short- and long-term contexts proceeding from the past to the future.

3.3. Materials and methods

3.3.1. Data collection

The data collection (the interviews and workshop) was planned essentially based on the theoretical framework and was, as such, theory-driven. The interviews were structured by themes designed according to the theoretical perspectives of distributive, procedural, recognition, and intergenerational justice. These themes were supplemented by emphasizing the interviewees’ perceptions of the local social context. The themes were (1) local livelihoods and industries, (2) communality, (3) regional identity, (4) governance, (5) participation and knowledge, (6) distribution of benefits and risks, and (7) future perspectives.

We conducted 21 interviews,35 where eleven informants were located in Sodankylä municipality, four in adjacent Savukoski municipality, and six in other parts of Finland. Some interviews were done remotely owing to COVID-19 restrictions or logistical issues. The interviewees represented actors from different industrial sectors (mining, reindeer husbandry, tourism), local and regional politics, state organizations involved in mining sector regulation, and local associations (hunting and fishing). There was some representation overlap between different sectors and levels of actors within the groups of interviewees. For example, one person worked as a reindeer herder and tourism entrepreneur. Another example was a tourism entrepreneur who was also a municipal council member. All interviews were semi-structured, focusing on different aspects of land-use projects, such as the distribution of benefits, governance, and participation.

In addition to the interviews, a workshop was organized for data gathering. It was held in Sodankylä using the Timeout method in February 2022. Timeout is a dialogue method for small groups using a trained facilitator to guide the discussion to develop a deeper understanding of the topic through dialogue between different actors on an equal footing.36 People from various local organizations were invited to the workshop. They represented a mining company, reindeer herding, municipal politics, tourism, and a local youth organization. It is worth highlighting that the workshop coincided with the commencement of the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Despite the emotionally charged backdrop, the participants and the organizers considered the event a success.

The interviews and workshop discussions were transcribed and anonymized using a basic transcription level, where speech is transcribed word-for-word using colloquial expressions, but filler words are left out. Finally, the data were entered into Nvivo37 software, which was used for coding the data set for a thematic analysis.

3.3.2. Methods

The data were analyzed using content analysis (CA). CA is a family of qualitative analysis methods which are essentially used for finding qualitative patterns in the data.38 The CA methods can be broadly divided into two main categories: inductive and deductive (theoretical) thematic analyses. In the former, the codes used for the study are generated from the data during the analysis. In the latter, the coding structure is developed from the research question and theory used for the analysis. We used the theory-driven thematic analysis process presented by Braun & Clarke.39

After the data had been transcribed, the initial codes were generated based on our theoretical framework, background knowledge, and previous research. The data were then coded according to these initial codes. After the first round of coding, the codes were reviewed and refined. The coded data set was then categorized into themes by content. Finally, the themes were reviewed and collated into broader categories.

The themes from the content analysis were then interpreted as (in)justice concerns. As the coding structure was developed from our theoretical framework, the resulting themes of the analysis were expressed with the concepts of this framework, and different forms of justice are represented in these themes. From these broader themes, we selected central perspectives and interpreted them as presentations of experienced injustices. We then condensed these perspectives into pragmatic claims for the legal assessment of the legal reforms.

In the legal analysis, we used the same forms of justice, namely distributive, procedural, recognition, and intergenerational justice, as in the analysis of the empirical material. The purpose of the legal analysis was to understand which substantial changes of the legal reforms are relevant from the perspectives of distributive, procedural, recognition, and intergenerational justice. This part of the analysis was conducted independently from the empirical analysis in the sense that it aims to explicate the content of the legal change expressed in its own terms. Finally, in the discussion part, we assess whether and to what extent the legal changes reflect the justice concerns of the stakeholders. In this part of the paper, we combine the results of the analyses of the empirical material and the legal changes.

4. Results of the empirical analysis

Based on our empirical data, this Section first presents justice concerns as they were expressed by the interviewees and workshop participants. Thereafter, we present an overview of each topic of justice concern and justice claims derived from these topics. Finally, the justice claims are described using examples from the data.

4.1. Distributive justice

Most local stakeholders considered distributive justice of utmost importance. First, those engaged in tourism and reindeer husbandry felt that they suffer from the adverse impacts of mining without sufficient compensation or any compensation at all. They felt that the brand of these nature-based livelihoods deteriorated because of nearby environmentally unfriendly mining operations.

Second, mining was thought to have impacted the local culture and way of life negatively. The subsistence and recreational uses of nature and the local environment, in the form of berry-picking, fishing, hunting, and other outdoor activities, are an integral part of the northern way of life, especially in remote and small communities such as Sodankylä. Therefore, most local interviewees considered it fundamentally unjust that the mining industry caused adverse impacts on the local way of life through dust and tailings drainage to the local hydrological system.

Both the timescales of benefits and environmental impacts and their distribution were considered problematic. Most informants viewed local benefits in the form of employment, tax revenue, and population growth as short-term benefits. Simultaneously, the local environmental impacts were considered long-term and permanent issues. In contrast, the interviewees pointed out that the global mining industry gained long-term benefits with relatively low costs. In their opinion, the global economy also benefits them, but they still considered the distribution of benefits and burdens unjust.

Claim 1: It is not just that existing industries and people employed by these businesses have to give up their interests to provide space for the mining industry.

“When the mine comes, then almost everything else has to move away. The opportunities other livelihoods might have in the mining area and its vicinity are gone.” (Interview, clerical worker, Indigenous Rights Organization)

Claim 2: It is not just that local people and their way of life suffer from adverse environmental impacts, while most economic benefits disappear from the region.

4.2. Procedural justice

Resources were strongly stressed as a justice issue. The interviewees and workshop participants felt that in addition to time, they needed more technical and financial resources for adequate participation in public procedures and negotiations with the mining companies. Assessment reports, technical plans, and other documents are large and complicated, and the sheer volume of the documentation related to mining-related processes can be massive. The lack of resources and the complexity of the processes produced asymmetrical power relations, and the local stakeholders felt that their limited resources undermined their ability to influence the processes.

Interestingly, the issue of resources was raised both by professionals and non-specialists. Industry representatives and government officials felt that the state side needed more expertise and resources in the regulatory processes. In addition, they saw a systemic problem in how the whole regulatory apparatus is set up. The current system divides permit processes between different agencies, which was considered ineffective, as it separates the expertise of officials from various agencies and makes the processes more complicated.

The issue of youth participation was a prevalent theme in the data. Youth were considered an important group in the local participatory processes, but their representation in them is scarce. As mining projects have long life cycles, the local youth are likely the group that will experience most of the benefits and impacts of the projects.

Claim 3: It is not just that the local stakeholders are not given enough time and expert resources to tackle the numerous technical details related to mining projects.

“When we go into these things and have thousands of pages long environmental impact assessments and mappings, reports, and this and that. And you are supposed to give comments and understand all that. It requires an incredible amount of work taken from actual work or leisure time.” (Interview, Reindeer herder)

“Time is the use of power. Even though the opportunity to comment is offered, it requires expertise and time. Then it is said that people have had an opportunity to influence, but in reality, it has been completely impossible because of the time constraints.” (Group discussion, local politician)

Claim 4: It is not just that the organizations regulating and monitoring the mining industry need more resources and expertise to carry out their tasks.

“We have good public administration, but their expertise and resources are a concern … that they have enough people and resources. The situation has been getting better, but there are still challenges.” (Interview, specialist, mining industry)

Claim 5: It is not just that local youth are not appropriately represented in the participatory processes.

“Often youth are missing from the negotiations with the villages. There are usually elderly people and pensioners participating. Where are the twenty- and forty-year-olds in the negotiations and hearings?” (Group discussion, reindeer herder)

4.3. Recognition justice

The municipality of Sodankylä is located on the southern border of the Sámi Homeland with five different reindeer herding cooperatives operating in the area (see Section 2.1.). There are reindeer herders in Sodankylä who identify themselves as Indigenous, but without the right to vote in Sámi Parliament elections. These people, who call themselves Forest Sámi, feel that they are not recognized as Indigenous and that the Sámi Parliament does not represent them in administrative processes such as issuing permits for mining operations. Whether or not these people should have the right to vote has polarized opinions among people living in Lapland and national political parties for a long time, and there seems to be no end to this conflict in the near future. Currently, it seems that whatever the solution to the issue is, some people will consider it unfair and unjust. Based on the views expressed in the interviews, the justice concerns relevant to recognition justice can be summarized as follows.

Claim 6: It is not just that not all Indigenous people are recognized as Indigenous, and that reindeer herding in some areas is considered an Indigenous culture and livelihood with strict protections, whereas in other areas it is regarded as a branch of agriculture with looser protections.

In the following Section, we will shed light on the key content of recent mining-specific legal reforms from the perspectives of distributive, procedural, recognition, and intergenerational justice. An assessment of the extent to which the justice concerns of stakeholders are reflected in the reforms is carried out in Section 5.

4.4. Intergenerational justice

A historical perspective on justice and a cumulative understanding of the benefits and impacts of mining were considered necessary by the majority of the stakeholders. While a mining project may have adverse impacts on people who do not benefit from it, it is even more problematic if the impacts are combined with adverse effects of other major land-use projects, such as forestry, artificial lakes made for hydropower, or other mining projects. Concurrent projects and past projects still affecting the current situation should be considered in addressing current justice issues.

After the Second World War, forestry and the building of artificial lakes strongly affected the landscape of Sodankylä. Currently, forestry continues and several wind farms are planned to be built in many places in Lapland, including Sodankylä. Therefore, the cumulative impacts of past and present projects should be considered as a whole, according to local stakeholders. Although the lapse between past and present projects may be several decades, residents still look at the impacts of new projects through the lens of historical development.

Claim 7: It is not just that the traditional local industries and residents of Sodankylä municipality must suffer from and adjust to the cumulative impacts of historical and new natural resource exploitation projects.

“We have a dark history of land use in the area [Sodankylä]. The locals have been tricked over the years. Positive things have been pushed to the background. All these land use projects have scarred the local communities.” (Group discussion, entrepreneur)

5. Analysis of legal reforms

Two mining-specific legal reforms were carried out in 2022 and 2023. Act 505/2023 amended the Mining Act (621/2011), and the Act on a Mined Minerals Tax (314/2023) introduced a new tax. In addition, the new Nature Conservation Act (9/2023) and the Act on the Environmental Damage Fund (1262/2022) are clearly relevant to mining operations.

Moreover, in 2022 the Finnish government prepared a proposal (274/2022) to reform the Act on the Sámi Parliament (974/1995). This reform failed. The key reason was disagreement concerning who would be eligible to vote in Sámi Parliament elections. The proposal would also have tightened the obligation40 of those performing public administrative tasks to negotiate and cooperate with the Sámi Parliament when preparing legislation, administrative decisions, and other measures considered of significance to the Sámi people. In other words, the Sámi Parliament would have had better opportunity to influence decisions relevant to mining operations in the Sámi Homeland. It is worth noting that there are currently no mines in the Sámi Homeland, but reservations for the preparation of exploration permits41 have been made by mining companies.

5.1. Distributive justice

The prevention and mitigation of harm is vital to the distribution of benefits and burdens. Not considering harm prevention and mitigation could result in the rejection of a mining permit, but the permit applicant would still bear the costs of preparing an application. Rejection rarely happens on these grounds. However, the wording of permit conditions in the Mining Act was changed.42 Previously the permit conditions imposed by the mining authority were imprecise to the extent that they were difficult to implement.43 Now the law provides explicitly the permit conditions that should be imposed.44 While this legal change does not expand the powers of the mining authority, the more explicit wording is supposed to change administrative practice. Moreover, a gold panning or exploration permit may not be granted if the activity in question causes significant harm to other livelihoods (Sec. 46).

Another reform concerns only one word, namely, the word ‘and’ was changed to ‘or’, yet it may turn out to be relevant in certain situations. Previously, a mining permit could not be granted if mining operations posed a danger to public safety, caused significant adverse environmental impacts, and substantially weakened the living and industrial conditions of the locality (i.e. other livelihoods), and the said danger or effects could not be eliminated utilizing permit regulations (Sec. 48). After the reform, a danger to public safety, adverse environmental impacts, or weakened living and industrial conditions may separately result in the rejection of a permit application.

Uncertainties caused by exploration projects are a burden to landowners. While an exploration project typically does not cause significant environmental impacts, it creates uncertainty as to what will happen in the future. This uncertainty tends to reflect on property prices. The maximum period of an exploration permit was shortened from 15 to 10 years in principle. However, if landowners whose property covers 50 percent of the exploration area give their consent, the permit can be extended. In Lapland, the most prominent landowner, the state, may alone own the area needed. Moreover, the Council of State may always allow the extension of a project of significant public interest (Sec. 61a).

The mining industry mainly bears the direct economic costs of the reforms. The figures of these costs arising from the government proposal are some millions of euros, which is a small amount compared to the turnover of mining companies. However, the most significant impacts of the proposal not included in the figures were estimated to result from reduced investments in Finland.45 While it is impossible to show whether or not the stricter legislation affects investments, it is likely that the mining industry in Finland, and particularly in Lapland, will grow due to megatrends and other polices discussed later.

The Mining Minerals Tax Act (314/2023) imposes a new tax on mining minerals. By its very nature, the tax model is analogous to a royalty-type payment. The tax on metal ores is 0.6 percent of the taxable value of the metal in the metal ore. The taxable value is assessed based on international market prices. The tax on mining minerals other than metal ores is EUR 0.2 per ton of mined minerals. The municipalities where mines are located account for 60 percent of the revenue while the rest goes to the state. The annual tax revenue is estimated to be approximately EUR 25 million, of which the municipalities’ share is EUR 15 million.46

5.2. Procedural justice

The major procedural reform concerns the role of local land use plans and hence the role of municipalities. After the reform, a local land use plan is a precondition for granting a mining permit (Sec. 47). Previously, a land use plan was not always required. Hence, the municipality may now use its land use planning powers to prevent the establishment of a new mine. This possibility increases the willingness of mining companies to listen to the desires of the municipality. Another procedural reform is the introduction of an obligation to organize annual open briefings where information about the project’s development is shared with the public. The responsibility for organizing these events lies with the permit holders of exploration and exploitation projects, yet in the case of gold panning, it lies with the mining authority (Sec. 14, 18, 28).

5.3. Recognition justice

The assessment procedure concerning the effects of Sámi Homeland-based mining projects on the Sámi was developed.47 The applicant must include an inquiry in the permit application regarding the effects of the activities on the right of the Sámi as an Indigenous people to maintain and develop their language, culture, and traditional livelihoods. The inquiry is also needed for projects located outside the Sámi Homeland, if the activities have significant relevance to the rights of the Sámi as an Indigenous people. Thereafter the Sámi Parliament, the Skolt Village Assembly, and relevant reindeer herding associations have an opportunity to comment on the inquiry report. While the assessment procedure as such is not new, the obligation of the applicant to make an inquiry and the right of Sámi people to comment on it are new legal elements. Another improvement concerns the sharing of information about reservation areas with the Sámi Parliament or the Skolt Sámi village assembly (Sec. 44).

A mining company’s task is to provide basic information, but the final assessment is to be made by the mining authority in cooperation with the permit applicant, the Sámi Parliament, the Skolt Village Assembly, the reindeer herding associations in the area, and the authority or institution responsible for managing the area. The purpose of the assessment is to identify measures necessary to reduce and prevent harm. This requirement is not new, except for the explicit reference to traditional livelihoods.

Another element that remains unchanged concerns the whole area designated for reindeer husbandry, which also covers areas other than the Sámi Homeland. In this area, the mining authority shall, in cooperation with the reindeer herding associations, investigate the adverse effects of mining projects on reindeer husbandry.

5.4. Intergenerational justice

Promoting intergenerational justice has not been an explicit objective of any of the reforms. Still, some aspects of the reforms may have long-lasting impacts on the living conditions of coming generations. The new Nature Conservation Act made national parks and nature reserves no-go zones for mineral exploration (Sec. 52 § 5), although a permit may still be granted for scientific geological research. Adopting the voluntary ecological compensation mechanism in accordance with the Nature Conservation Act (Sec. 98–107) is a measure to mitigate environmental harm and has the potential to mitigate cumulative impacts on nature. However, due to its voluntary nature, it is hard to predict the outcome. In addition, the new Act on the Environmental Damage Fund created a system of secondary liability for environmental damage, covering situations of insolvency and unknown polluters (1262/2022).

6. Discussion

In this Section, we discuss whether and to what extent the justice concerns of stakeholders are manifested in the legal reforms. Both the empirical analysis of stakeholders’ justice concerns and the legal analysis of the reforms were structured according to the key theoretical concepts presented in Section 3.2. In the empirical analysis, we did not request the opinions of the stakeholders on the content of the legal reforms, which were still in preparation during the material gathering phase. Instead, we let the stakeholders express justice concerns as they understood them, with the result that they used their own and sometimes unspecific language. Consequently, the justice concerns should be understood as the stakeholders’ general views of the reform-related issues they were asked to address. We discuss the relationship between the justice concerns and the reforms from this perspective.

As discussed above, most of the justice concerns expressed by the stakeholders have been addressed in the studied legal reforms – but only to a certain extent.

From a distributive justice perspective, the legal requirements protecting the environment and local livelihoods have clearly become stricter and the cost of mining has increased. In other words, the balance of burdens and benefits has changed. Putting the legal changes in a broader context, the most fundamental features of the governance of mining activities have remained unchanged. By its very nature, the Finnish system of mineral ownership is still a claim system, albeit not a pure one. The two other main alternatives for mineral ownership are the concession system and the land ownership system.48 The exploitation of mineral resources is based on the market economy, and state authorities are obliged to grant mining, environmental, and water permits if applications meet the legal criteria. The role of the land use plan will be discussed later.

The changing balance of burdens and benefits will not change the megatrends affecting the mining industry. The demand for minerals – and hence the mining industry – is likely to grow globally in the future due to the green and digital transitions and economic growth.49 Moreover, in response to increasing geopolitical risks and other megatrends, the EU Commission has adopted a critical raw material policy50 and made a legislative proposal called ‘the European Critical Raw Materials Act’.51 The proposal aims, among other things, to reach the untapped potential of the EU supply of minerals. It contains measures ensuring improved access to funding and streamlining, and increasing their predictability, yet in compliance with the environmental acquis and common standards for public engagement. In Finland, the national battery strategy aims to take full economic benefit from domestic mineral resources by improving the value chain from mineral extraction to valuable products.52 According to the government proposal for the Mining Act, the impacts of the reform, both on other livelihoods and its positive environmental and climate impacts, are relatively minor.53 Still, some developments have taken place. The other studied reforms also contribute to a change in the balance of burdens and benefits. The Nature Conservation Act prohibits mineral exploration in national parks and nature reserves, while the Act on the Environmental Damage Fund ensures the availability of financial resources for ecological restoration and damage compensation in the case of insolvency or an unknown polluter. These reforms can be seen as partial responses to the second justice claim. However, it would not be justified to conclude that the justice concerns of the stakeholders as captured in the first two justice claims would be fully solved by the reforms.

To keep broader development in mind, it is important to note that the interpretation of the Environmental Protection Act (527/2014) has become much stricter, affecting the level of environmental performance required from mining operations. This is relevant, although it is not related to the studied reforms. Based on the Water Framework Directive (2000/60/EC) and the Weser ruling (C-461/13) of the European Court of Justice, the Finnish Supreme Administrative Court (KHO 2022:38, Sokli mine) recently set very strict requirements for environmental impact assessment in the context of environmental permits. This also indicates that very strict conditions will be expected to be set in environmental permits. This would be in line with the development in other fields of industry. A few years earlier, the Supreme Administrative Court (KHO:2019:166) exceptionally rejected the permit application of a large bioproduct mill based on the Weser ruling. The Court was not convinced that the mill at the site in question and the planned production volume would not cause significant pollution to the receiving water body during the mill’s entire life cycle, taking into account the development of the ecological status of the water body.

A key objective of the Mining Act reform was to increase local acceptability and opportunities to exert influence. To make this objective a reality, the position of the local land use plan was strengthened. This is a continuation of the devolution of power to the local level, which started in 2011.54 Hence, it becomes even more important for mining companies to achieve a ‘social license to operate’ (SLO)55 and to consider the standpoints of the local communities. While local stakeholders in the interviews saw this development in a positive light, they still pointed out that the interests of individuals and the municipality may not necessarily go hand in hand, and the municipality remains in a weak position in comparison to big international mining companies. The stakeholders formulated their procedural justice concerns (justice claims 3 and 4) in such a way that they also applied to the municipality. They noted that in addition to individuals, municipalities also suffer from a lack of expertise and time. In other words, the strengthened position of the local land use plan does not alone have a significant effect on the acceptability of mining operations.

Still, this legal change may reduce the volume of mining activities from that planned by mining companies in individual municipalities regardless of the megatrends described above. Whether municipalities will use this opportunity is another issue. Often, local decision-makers favor mining projects because of their economic impacts, regardless of the conflicts involved. In some municipalities, for example in Sodankylä, most residents have a positive attitude toward mining.56 Mining taxes will make the projects even more attractive from the local economy point of view. The amount of taxation is significant compared to other taxes collected directly from mining companies.57

However, differences exist between municipalities. There are also municipalities where tensions between tourism and mining have caused significant conflicts and affected the attitudes of decision-makers.58 A well-known case is that of Kuusamo, where the municipality prepared a land use plan before the reforms limiting mining close to a tourist resort. This case shows that a municipality may not use the tool of land use planning in any way they want. Namely, the Supreme Administrative Court retained the decision of a lower court to revoke the land use plan.59 The Court considered that the provisions prohibiting mining activities could not be regarded as provisions to prevent or limit adverse environmental effects within the scope of the Land Use and Building Act (132/1999). The Court ruled that instead of directly concerning environmental impacts, the provisions dealt with the prohibition of certain business activities. The case has not lost its relevance after the reforms. Currently, a municipality may decide not to adopt a land use plan at all with the effect that a mining permit may not be granted. However, if a land use plan is adopted, the rules of legislation on land use planning must be followed.

Other procedural changes are of minor relevance, although annual briefings, where local people may hear about recent developments in mining activities, will make the mining industry somewhat more transparent. The fifth justice claim concerning the representation of young people was not addressed in any way in the reforms. It seems that legislators consider this an issue of implementation.

As for recognition justice, the key improvement of the reforms concerns the assessment of the effects of a mining project on the Sámi. This legal change strengthened the position of the Sámi Parliament and the Skolt Village Assembly. However, this is not relevant regarding the sixth justice claim, which was presented by people not eligible to vote in the Sámi Parliament election. Still, it is important to note that reindeer herding associations in the area designated for reindeer husbandry have a special position in the participation procedure, and in reindeer herding areas outside the designated area, these associations may rely on the general right to participate in decision-making. However, the disputed justice concern expressed in the sixth justice claim was not apparent in the legal reforms. Whether this claim should have been considered is an issue outside the scope of this study.

The proposal for the amendment of the Act on Sámi Parliament failed to be approved by the national Parliament. It would have been an implementation measure of the principle of Free, Prior, and Informed Consent of Indigenous People,60 and this was the third time that the reform of the Act was rejected. The reason has always been same, namely, disagreement about who has the right to vote in Sámi Parliament elections. The majority of the Sámi Parliament supported the proposal. Disagreement on this matter is strong and long-lasting. The new national government formed in the spring of 2023 is committed to continuing to try to find a solution so that an agreement on the reform of the Act on Sámi Parliament can be reached.

Intergenerational justice concerns were not explicitly addressed in the legal reforms. Many stakeholders claimed in the interviews that history is not considered the way it should be. They claimed that historically natural resources in Lapland have been exploited for the benefit of people who live far away, and now new mining projects are continuing this practice. The interviewees pointed out that even if the adverse impacts of a single project would be tolerable, the real problem is the cumulative impacts of many natural resource projects over time. We got the impression that particularly reindeer herding families think that the areas where large-scale artificial lakes have been constructed should be no-go zones for future large-scale natural resource projects to ensure maintenance of traditional livelihoods and culture. This issue was not addressed in the legal reforms, and there is no indication that it will become the subject of serious political debate, either.

7. Conclusions

We have identified mining-related justice concerns expressed by local stakeholders in Finnish Lapland and assessed how these concerns were addressed in recent mining-related legal reforms in Finland. The assessment was made from the perspectives of distributive, procedural, recognition, and intergenerational justice. The reforms were not designed to change the fundamental features of the governance of mining activities or to limit their total volume. By its very nature, the Finnish system of mineral ownership has remained a claim system, albeit not a pure one. The mineral industry is likely to grow in the future globally and in the Arctic due to an increasing demand accelerated by the green and digital transitions. As a result, mining conflicts and justice concerns are unlikely to disappear.

The introduction of a new mining tax and more explicit regulation concerning mining permit conditions contribute to distributive justice. Mining tax revenues will increase the financial resources of municipalities, but they will not change things dramatically. The more explicit wording of permit conditions in the Mining Act only aims to improve poor implementation. The exploration of mineral resources is, in principle, forbidden in national parks and nature reserves but not in other protected areas, which constitute most of the areas under protection. A mechanism of ecological compensation has been introduced, but its utilisation is voluntary.

In terms of procedural justice, one major legal reform concerns the position of the municipality. The local land use plan has become a clear precondition for granting a mining permit. While this is an important reform, perhaps the most important of them all, it is not a full-size revision, since municipalities did play a role in decision-making earlier as well. Another procedural reform is the obligation of the exploration and mining operators and the mining authority to arrange annual information-sharing events. However, this is only a mild response to the lack of time and expertise that renders residents incapable of understanding the complexities of a mining project.

From the perspective of recognition justice, the process of assessing the effects of mining operations on the Sámi as an Indigenous people was improved, although the government proposal for amendment of the Sámi Parliament Act failed to be approved by the national Parliament. As for intergenerational justice, the prohibition of mineral exploration in national parks and nature reserves and the introduction of the Environmental Damage Fund are positive reforms. Protected areas contribute to the protection of biodiversity and advance the local tourism industry, while the Fund allocates the financial responsibilities of secondary liability more justly than before. Many stakeholders regarded the cumulative impacts of several natural resource projects over a long period of time as the most fundamental problem. The reforms did not address this issue.

To sum up, it can be concluded that the mining relevant legal reforms carried out in the years 2022 and 2023 in Finland addressed most of the justice concerns expressed by the local people in Finnish Lapland, but only to a certain extent. Some of their concerns were fully unrecognized by the legislators. The debate over what kind of legal regulation is just will continue.

Acknowledgements

The preparation of this article has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 869327.

NOTES

- 1. Pasi Eilu (ed.), “Mineral deposits and metallogeny of Fennoscandia”, Geological Survey of Finland, Special Paper 53, 2012.

- 2. https://saimaailmankaivoksia.org/; https://proheinavesi.weebly.com/english.html

- 3. https://eikaivoksille.wordpress.com/; https://rajatlapinkaivoksille.fi/

- 4. Inclusive and Competent Finland – a socially, economically and ecologically sustainable society (2019). Programme of Prime Minister Sanna Marin’s Government 10 December 2019. Publications of the Finnish Government 2019:33. Government Administration Unit, Publications. Helsinki, 2019. These objectives were included also in the Government proposal (126/2022) for the amendment of the Mining Act, at 1.

- 5. Map (Appendix).

- 6. Official Statistics of Finland (OSF): Population structure [online publication]. ISSN=1797-5395. Helsinki: Statistics Finland [Referenced: 1.6.2023]. Access method: https://stat.fi/en/statistics/vaerak

- 7. Official Statistics of Finland (OSF): Labour force survey [online publication]. ISSN=1798-7857. Helsinki: Statistics Finland [Referenced: 1.6.2023]. Access method: https://stat.fi/en/statistics/tyti

- 8. Ibid.

- 9. Official Statistics of Finland (OSF): Population structure [online publication]. ISSN=1797-5395. Helsinki: Statistics Finland [Referenced: 7.11.2023]. Access method: https://stat.fi/en/statistics/vaerak

- 10. Figure (Appendix).

- 11. Finnish Network for Sustainable Mining, Responsibility Report 2021, https://www.kaivosvastuu.fi/yrityskortti/boliden-kevitsa-mining-oy-2021/

- 12. Finnish Network for Sustainable Mining, Responsibility Report 2021, https://www.kaivosvastuu.fi/yrityskortti/2021-rupert-finland-oy-2/

- 13. Finnish Network for Sustainable Mining, Responsibility Report 2021, https://www.kaivosvastuu.fi/yrityskortti/aa-sakatti-mining-oy-2021/

- 14. Map (Appendix).

- 15. Leena Suopajärvi, “Vuotos- ja Ounasjoki- kamppailujen kentät ja merkitykset Lapissa,” Acta electronica Universitatis Lapponiensis (2001), University of Lapland.

- 16. Kauko Puustinen, “Mining in Finland during the period 1530–1995,” ed. Sini Autio. Geological Survey of Finland, Current Research 1995–1996, Special Paper 23, 43–54.

- 17. Ibid.

- 18. Pasi Eilu, “Mineral deposits and metallogeny of Fennoscandia,” Geological Survey of Finland, Special Paper 53:401.

- 19. Heino Vasara, Kaivosalan toimialaraportti, Ministry of Economic Affairs and Employment Publications 2019:57, http://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-952-327-462-4 (accessed June 1, 2023).

- 20. Kuisma, Marianne and Suopajärvi, Leena (2017), “Social Impacts of Mining in Sodankylä,” https://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-952-484-971-5 (accessed June 1, 2023).

- 21. Mari Tulilehto and Suopajärvi Leena, Experienced Impacts of Mining in Sodankylä: Follow-up Study, https://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-952-337-090-6 (accessed June 1, 2023).

- 22. Raphael Heffron and Darren McCauley, “What is the ’Just Transition?’,” Geoforum 88 (2018), 74–77; Kirsten Jenkins, Darren McCauley, Raphael Heffron and Hannes Stephan, “Energy justice: A conceptual review,” Energy Research & Social Science 11 (2016), 174–182; Julian Lamont and Christi Favor, “Distributive Justice”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2017 Edition), https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2017/entries/justicedistributive/ (accessed June 1, 2023); David Miller, “Justice,” The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (2021), https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2021/entries/justice/ (accessed June 1, 2023).

- 23. David Hume, A treatise of human nature (Oxford philosophical texts, 2000), original text 1739–40; Jeremy Bentham, The principles of morals and legislation, 1988 (Prometheus, 1988), original text 1781.

- 24. Immanuel Kant, On history, Idea for a universal history from a cosmopolitan point of view (The Bobbs-Merrill Co., 1963), original text 1784; Garret Hardin, “The Tragedy of the Commons: The population problem has no technical solution; it requires a fundamental extension in morality,” Science 172:3859 (1968).

- 25. Olivier Godard, Global Climate Justice: Proposals, Arguments and Justification (Edward Elgar Publishing, 2017); Tracey Skillington, Climate Justice and Human Rights (Palgrave Macmillan US, 2017).

- 26. Tracey Skillington, Climate Change and intergenerational Justice (Routledge, 2018); Pranay Sanklecha, “Our obligations to future generations: the limits of intergenerational justice and the necessity of the ethics of metaphysics,” Canadian Journal of Philosophy 47:2–3 (2017).

- 27. Julian Lamont and Christi 2017.

- 28. Raphael J. Heffron and Darren McCauley, “Achieving sustainable supply chains through energy justice,” Applied Energy 123 (2014).

- 29. Gottfried Schweiger, “Recognition, misrecognition and justice,” Ethics & Global Politics 12 (2019), 11–20.

- 30. Nancy Fraser, “Reframing Justice in a Globalizing World,” New Left Review 36 (2005); Nancy Fraser, “Feminist Politics in the Age of Recognition: A Two-Dimensional Approach to Gender Justice,” Studies in Social Justice 1:1 (2007); Axel Honneth, “Recognition and Justice: Outline of a Plural Theory of Justice,” Acta Sociologica 47: 4 (2004).

- 31. Vasna Ramasar, Henner Busch, Eric Brandstedt, and Krisjanis Rudus, “When energy justice is contested: A systematic review of a decade of research on Sweden’s conflicted energy landscape,” Energy Research & Social Science 94 (2022).

- 32. Johanna Ohlsson and Tracey Skillington, “Intergenerational Justice,” in Theorising Justice: A Primer for Social Scientists ed. Johanna Ohlsson and Stephen Przybylinski (Bristol University Press, 2023).

- 33. Gregory Poelzer and Thomas Ejdemo, “Too Good to be True? The Expectations and Reality of Mine Development in Pajala, Sweden,” Arctic Review on Law and Politics, vol. 9, no. 1 (2018): 3–24; Simon Haikola and Jonas Anshelm, “The making of mining expectations: mining romanticism and historical memory in a neoliberal political landscape,” Social & Cultural Geography, vol. 19, no. 5 (2018): 576–605.

- 34. Andre Santos Campos, “Intergenerational Justice Today,” Philosophy Compass 13 (2018): e12477, 4–6; Tracey Skillington, “Changing perspectives on natural resource heritage, human rights, and intergenerational justice,” The International Journal of Human Rights 23, no. 4 (2019): 615–637; Edith Brown Weiss, “Climate Change, Intergenerational Equity, and International Law,” 9 Vt. J. Envtl. L. 615–627 (2008), https://ssrn.com/abstract=2734420; Jonathan White, “Climate Change and the Generational Timescape,” The Sociological Review 65, no. 4 (2017): 763–778.

- 35. Table (Appendix)

- 36. Timeout Foundation, What’s Timeout about? https://www.timeoutdialogue.fi/whats-timeoutabout/ (accessed: 10.11.2022)

- 37. QSR International Pty Ltd. (2020) NVivo (released in March 2020), https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home

- 38. Virginia Braun and Victoria Clarke, “Using thematic analysis in psychology,” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3:2 (2006); Hsiu-Fang Hsieh and Sarah E. Shannon, “Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis,” Qualitative Health Research (2005); Lorelli S. Nowell, Jill M. Morris, Deborah E. White, and Nancy J. Moules, “Thematic Analysis: Striving to Meet the Trustworthiness Criteria”, International Journal of Qualitative Methods 16 (2017).

- 39. Virginia Braun & Victoria Clarke, Using thematic analysis in psychology, 87.

- 40. Section 9 of the current law (974/1995). The government proposal (274/2022) would have changed this Section and introduced new Section 9a.

- 41. https://www.samediggi.fi/2021/12/21/saamelaiskarajat-vastustaa-lapin-paliskunnan-alueenkaivostoimintaan-tahtaavia-hankkeita/

- 42. Government proposal for the amendment of the Mining Act, Government Proposal 126/2022, 107–108.

- 43. The imprecision of the permit conditions was a key reason why the Supreme Administrative Court (6026/2017) overturned a mining authority’s decision and referred the matter back to the mining authority for reconsideration.

- 44. The Sec. 52 requires that permit conditions concerning (1) the preservation and renewal of trees and other vegetation and new plantings during mining; (2) the location of activities in the mining area, taking into account impacts on biodiversity and other environmental impacts; (3) measures to prevent significant adverse effects on the environment; (4) measures to prevent significant deterioration in the settlement or economic conditions of the locality; and (5 ) on the gradual closure of the mine are included in a mining permit, if needed.

- 45. Government proposal (126/2022) for the amendment of the Mining Act, at 63.

- 46. Government proposal 281/2022, 18.

- 47. For the legal situation prior the reform, see Timo Koivurova et al., “Legal Protection of Sami Traditional Livelihoods from the Adverse Impacts of Mining: A Comparison of the Level of Protection Enjoyed by Sami in Their Four Home States” Arctic Review on Law and Politics 6 (2015): 11–51.

- 48. Eva Liedholm Johnson, “Mineral Rights – Legal Systems Governing Exploration and Exploitation,” (Stockholm: Royal Institute of Technology 2010). PhD dissertation, KTH; Eva Liedholm Johnson and Magnus Ericsson, “State ownership and control of minerals and mines in Sweden and Finland,” Mineral Economics 28 (2015), 23–36.

- 49. International Energy Agency, The Role of Critical Minerals in Clean Energy Transitions, 2021 The Role of Critical Minerals in Clean Energy Transitions – Analysis – IEA

- 50. The first list of critical raw materials was published 2011 in Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions, Tackling the Challenges in Commodity Markets and on Raw Materials, COM(2011) 25 final.

- 51. Proposal for a regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council establishing a framework for ensuring a secure and sustainable supply of critical raw materials and amending Regulations (EU) 168/2013, (EU) 2018/858, 2018/1724 and (EU) 2019/102. COM(2023) 160.

- 52. National Battery Strategy 2025, Publications of the Ministry of Economic Affairs and Employment, Enterprises, 2021:6.

- 53. Government proposal (126/2022) for the amendment of the Mining Act, at 64 and 66.

- 54. See for an overview of regulation prior to recent reforms, Jukka Similä and Mikko Jokinen, “Governing conflicts between mining and tourism in the Arctic,” Arctic Review on Law and Politics 9 (2018).

- 55. Pamela Lesser, Katharina Gugerell, Gregory Poelzer, Michael Hitch, Michael Tost, “European mining and the social license to operate,” The Extractive Industries and Society, 8:2 (2021); Koivurova TM, Buanes A, Riabova L, Didyk V, Ejdemo T, Poeltzer G et al., ‘Social license to operate’: a relevant term in Northern European mining? Polar Geography. 2015 Oct 29. Epub 2015 Oct 29

- 56. Mari Tulilehto and Leena Suopajärvi 2021.

- 57. Government proposal (281/2022) for Mining Minerals Tax Act, at 11.

- 58. Jukka Similä and Mikko Jokinen, “Governing conflicts between mining and tourism in the Arctic,” Arctic Review on Law and Politics 9 (2018).

- 59. Supreme Administrative Court case KHO 2019:67.

- 60. Government proposal (274/2022) for the amendment of the Sámi Parliament Act, at 46.

8. Appendix

Map of Sodankylä

| Role | Sector | N |

|---|---|---|

| Activist | Environmental Protection | 1 |

| Administration | Indigenous | 1 |

| Association Activist | Outdoor and nature | 2 |

| Civil servant | Public administration | 2 |

| Entrepreneur | Tourism | 4 |

| Management | Mining industry | 1 |

| Management | Mining industry | 1 |

| Management | Reindeer husbandry | 1 |

| Politician | Municipal politics | 2 |

| Politician | Regional politics | 1 |

| Reindeer herder | Reindeer husbandry | 1 |

| Specialist | Mining industry | 3 |