1 Introduction

This article addresses the clash between Western and Indigenous understandings of how cultural heritage should be governed, protected and treated through intellectual property rights (IPR) by using a single, intrinsic and descriptive case study: the Digital Access to Sámi Heritage Archives project (DigiSamiArchives). The overall interest of the article is approached through two research questions. First, we ask whether the clash between Western legal systems – in general – and the expectations of Indigenous people in terms of the possibility to protect, access, use and preserve cultural heritage is caused by the governance models currently in use. This represents a starting point for us to engage with the second – and main – question, where we ask what are the challenges raised specifically by the IPR system in the context of this clash. Both questions focus especially on the extent to which these clashes occur in the digital environment. We dig into the foundations and constructions of the mainstream Western IPR system in order to shed light on the contrasts that these structures create in respect to Indigenous people’s worldviews on the matter, both theoretically and empirically through the analysis of the DigiSamiArchives case. Ultimately, this enables us to propose more workable, inclusive and ethically respectful solutions for how to support the IPR system through soft-law mechanisms, such as ethical guidelines, to enable it to align and reconcile with Indigenous worldviews.

The DigiSamiArchives project ran during 2018–2021. The purpose of the project was to improve accessibility to the cultural heritage of the Sámi people, an Indigenous group living in the area of Sápmi, which today consists of northern parts of Finland, Sweden, Norway and Russia. Sámi cultural heritage materials exist in several archives and collections. For historical reasons artefacts have also been stored in museums and collections in Europe. The project developed a technical solution for gathering information and materials about the Sámi cultural heritage from different archives and collections in an easy and cost-effective manner. These materials consisted of, for instance, photographs and text documents, the use of which is usually governed and limited by IPR. Therefore, this project represented a critical and exemplary case with which to conduct and instruct our analysis and identify our research questions.

Defining what cultural heritage consists of is an ongoing process and not without ambiguities. Article 31 of The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) states that:

Indigenous peoples have the right to maintain, control, protect and develop their cultural heritage, traditional knowledge and traditional cultural expressions, as well as the manifestations of their sciences, technologies and cultures, including human and genetic resources, seeds, medicines, knowledge of the properties of fauna and flora, oral traditions, literature, designs, sports and traditional games and visual and performing arts. They also have the right to maintain, control, protect and develop their intellectual property, their cultural heritage, traditional knowledge, and traditional cultural expressions.

This clause demonstrates the holistic nature of cultural heritage. Indeed, the cultural heritage of Indigenous people covers the whole living environment and practices that take place there. In the specific case of the Sámi cultural heritage, the ethical guidelines for responsible Sámi tourism define Sámi culture as including:

among others, the Sámi language, Sámi cultural heritage, cultural expressions, Sámi art, traditional knowledge of the Sámi, the relationship of the Sámi with nature, traditional Sámi livelihoods and the modern ways of practising them as well as other cultural customs and manifestations practised by the Sámi as an Indigenous people.1

This article builds on these definitions, also keeping in mind that, as Jelena Porsanger and Pirjo Virtanen have noted, “cultural heritage is not a concept with one definition only, and it is obvious that in Indigenous understandings there is not one single, overall concept of cultural heritage”.2

The history of the cultural heritage of the Sámi as an Indigenous people in the Nordic countries, namely Finland, Sweden and Norway, has been characterised by many difficulties and misappropriations. As Rauna Kuokkanen, for example, has noted, assimilation policies and so-called settler-colonialism are still ongoing processes.3 Whereas issues related to land rights are today perhaps easier to recognise, colonialism also takes other forms, one of which is cultural appropriation. Cultural appropriation essentially means that those elements of Sámi culture which the Sámi have been shamed and even punished for, are used by the majority population in an exotic manner, often for business purposes, and without the consent of Indigenous people who should be recognised as owners of the cultural elements involved. Moreover, the profits deriving from these types of activities stay with the majority population.4 These concepts are already familiar from discussions on “orientalism”, the way in which Europe built its common identity by means of defining “oriental” as “others”.5 This is essentially a relationship of power; the conceptualisation of “orient(al)” as “the other” includes a supposition of the superiority of Western values and thought systems as well as stereotypical notions of those “others” as exotic, primitive and irrational. Similar tendencies can still be seen in the discourse relating to the Sámi in Finland, where the Sámi are either exoticised, as in tourism, or depicted as “greedy, quarrelling and unable to think or cooperate beyond narrow personal or tribal interests”.6

Although cultural appropriation is not a new phenomenon, many new concerns have been raised regarding technological developments, such as digitalisation, and its consequences on, for example, access to the Sámi cultural heritage. While access to cultural heritage materials is often in the interests of the Sámi themselves, it makes appropriation easier. Increased access brings opportunities, challenges, and completely new issues to consider, not least in relation to ethics and the ethical use of digital technologies in (Indigenous) cultural heritage. Beyond efficiency the challenge remains regarding how to provide the right incentives through law to design and use solutions so that “cultural sensitivities”, which are by definition intrinsic elements of the heritage of Indigenous cultures, are respected, preserved and further developed. Importantly, the legal structures on which the whole system for accessing and protecting cultural heritage is built upon – such as the governance models used to make it accessible and the foundations and practices of intellectual property law and rights used in this context – are particularly problematic. For example, concepts such “access” or “publicly available documents” or “works in the public domain” might be understood and interpreted very differently in Indigenous communities, compared to Western societies. As Bowrey and Anderson argue:

These idealistic political and cultural concepts were, and arguably still are, largely experienced by Indigenous people as terms of exclusion. These were the very terms that justified the denials of sovereignty, dispossession of culture and lands and removal of Indigenous children from their families and communities.7

Amongst the various forms of cultural heritage artefacts, this article centres on digital archive materials, as they are the focus of the DigiSamiArchives project – our case study. However, we do not discuss archive materials or archive legislation as such, but rather concentrate on clashes between Indigenous views and Western IPR, and the reasons for this clash, by discussing the DigiSamiArchives project case, where certain potential clashes between Indigenous views and Western mainstream IPR tools and governance models can be observed. Furthermore, and on the basis of this analysis, the article develops recommendations for what could be done in terms of Western IPR legislation in order to enable Indigenous people’s views to be included, thereby enabling them to exercise their right to self-determination, as enshrined in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) Article 3 and also, in the context of Sámi, in Article 17 of the Finnish Constitution.8

2 The Sámi people, governance of their cultural heritage and IPR

2.1 Governance models for cultural heritage – centralised and decentralised approaches

While there are many different definitions for governance, in this article our starting point is the understanding of governance as a network of practices formed essentially by the exercise of power. Indeed, as Grazia Borrini-Feyerabend and Rosemary Hill define the concept, whereas management refers to what “is done in pursuit of given objectives and the means and actions to achieve such objectives”, governance is about “who decides what the objectives are, what to do to pursue them and with what means as well as how those decisions are taken, who holds power, authority and responsibility and who is (or should be) held accountable.”9 Thus, while governance is about what is concretely done, it is even more about who decides the limits of what can be done in the first place. As Sam Grey and Rauna Kuokkanen note, “every society has its own governance systems and ways of expressing and describing how it governs.”10 Governance thus includes the ways in which people choose “collectively, how they organise themselves to run their own affairs”,11 including choosing, for example, how to make decisions, share power and deal with internal dissent.12

Governance models are not only legal instruments, such as copyright legislation, but also consist, for example, of policies behind legislation, practices of implementing decisions that have been made, practices that define who takes part in the decision-making in the first place and dispute resolution mechanisms. In this article, we focus on how cultural heritage is governed in general as well as in the context of our case study.

Cultural heritage is a common-pool resource:13 property rights to cultural heritage are not explicitly defined (in Western legal meaning); however, they can be appropriated by private actors. Most cultural heritage is tangible as artefacts, and so, in economic terms, they are rivalrous: their consumption by one consumer prevents simultaneous consumption by other consumers.14 At the same time cultural heritage is also intangible and so non-rivalrous, as it may be consumed by one consumer without preventing simultaneous consumption by others. These kinds of intangible cultural heritage include, for instance, significances described in the Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage15 that are not connected to economic value. While use of artefacts is often both rivalrous but also excludable (one’s use excludes others’ access to the good) intangible cultural values can be shared and are non-excludable, in that they can be accessed simultaneously by several people.16 As such, cultural heritage cannot be described as a club good, which is non-rivalrous and excludable17 such as cable television or computer software. On the other hand, a non-rivalrous good such as tourism can become rivalrous due to high resource appropriation, or congestion, as clearly seen during the Covid-19 pandemic.

The traditional solution for the governance of common-pool resources has been privatisation.18 However, due to the communal nature of cultural heritage, privatisation has led to appropriation and exploitation by economic actors. Conventionally, attempts to prevent exploitation have been through regulation and state “ownership” (such as state ownership of land), leading to state exploitation (for example, the exploitation of forests for commercial purposes instead of using the forests for communal Indigenous purposes like reindeer herding). With regard to privatisation, the role of contracting increases. In terms of contract-based governance models, legislation is usually much more flexible than when cultural heritage is thought of as a human right, for example. This brings us to the complexity of governing cultural heritage. While cultural heritage materials are often conceptualised as being under the jurisdiction of property rights and the field of private law, they also have a connection to Indigenous peoples’ self-determination, which in Finland is enshrined in the Constitution. Thus, cultural heritage cuts across the traditional divisions between public and private law. Moreover, as will be discussed more thoroughly in relation to our case study, the governance of cultural heritage materials can be strongly contract-based.

As a solution to the so-called “tragedy of the commons”, Eleanor Ostrom has suggested voluntary and participatory self-governance by local stakeholders.19 Similar participatory governance models have also been proposed by the Open Method of Coordination (OMC) Working Group of Member States’ experts.20 Self-governance can be described as decentralised governance of common-pool resources, as opposed to centralised governance by, for instance, state authorities. Governance can be centralised globally, as in the case of trade in the hands of the World Trade Organisation, or by trans-national institutions, such as the European Union, or at the national level. Governance can also be decentralised on lower levels, for example in education or healthcare by devolution to municipalities and communities. As noted, though, in terms of governance of cultural heritage, centralisation means governance by the state and decentralisation by local cultural communities.

Self-governance has also been discussed in the context of Indigenous research. For example, Sam Grey and Rauna Kuokkanen note that:

self-determination is the foundational norm of international law bestowed to all peoples, including Indigenous peoples, and “governance” (or “self-government”) is the practical shape it takes in the political-legal realm. It is thus properly under this rubric that the protection of “cultural heritage” ultimately resides.21

Indigenous peoples’ self-governance and self-determination are thus interwoven: self-governance is a means of realising self-determination. As Grey and Kuokkanen further note, “it is the right to and practice of self-determination that enables Indigenous peoples to remain distinct, by practicing their own laws, customs, and land tenure systems through their own institutions, in accordance with their traditions”, in other words, to implement their own governance models.22

2.2 IPR and Indigenous cultural heritage: contradictory foundations?

Discussions on IPR and the cultural heritage of Indigenous peoples have been relatively widespread and have included Sámi perspectives. As a general starting point, Western IPR legislation on Indigenous cultural heritage is at times notably in contrast with Indigenous worldviews and forms of self-governance. One of the key reasons for the clash can be found in the colonial past suffered by Indigenous communities. For instance, it is very often the case that materials and IP rights related to Indigenous cultural heritage are kept or managed by organisations that are not representative of Indigenous worldviews and practices, for the simple fact that museums and archives are usually state entities (reflecting the centralised governance model described above). Because of this, decisions affecting materials are also mainly taken from the Western viewpoint.

Some of the theories currently used to justify IPR, such as utilitarian theories that prioritise economic efficiency and profit maximisation,23 are often in contrast with Indigenous worldviews and, as a consequence, many constructions of the Western IPR system are not suitable for Indigenous cultural heritage. For instance, certain basic concepts in IPR, such as the concept of exclusivity and ownership, are not in line with how these same concepts are understood from the perspective of Indigenous worldviews. In most Western IPR systems, exclusivity refers to the fact that an IP owner has the right to exclude others from doing certain things (for example, copying, making, using, distributing) with a protected work or innovation. This approach differs from the Indigenous approach, which understands exclusivity through law in order to preserve ownership – not by excluding others, but by harmonising multiple interests.24 Moreover, the Western role of IPR is focused on commercial activities and commoditisation – as opposed to collective ownership and communal character, which Indigenous worldviews tend to lean towards. For instance, the duration of IPR protection often serves commercial rather than cultural interests.25 All these features are particularly relevant when we look at Indigenous cultural heritage, which is a resource normally owned by communities, rather than individuals.26

All this has led to several detrimental activities such as appropriation of Indigenous culture and knowledge, as these practices are not necessarily forbidden by the mainstream IPR system.27 For instance, the case of Disney’s blockbuster animated feature film Frozen (2013) is particularly representative here. Frozen takes place in an Arctic environment and includes elements borrowed from Sámi culture. Even though Disney generated massive profits by using the Sámi heritage, the Sámi community did not obtain any kind of compensation for this. In an absurd twist, the current IPR system could have enabled Disney to claim copyright protection for some of the Sámi elements it uses in its animation, or even register them as its own trademarks. Another example is represented by the case where in 2020 the British Museum made available online Indigenous cultural heritage materials that included pictures of human remains, which are often considered to be highly sensitive.28 These materials were made free to use under a Creative Commons 4.0 licence.29 Similarly, in the same year the Finnish Heritage Agency released over 200,000 images online under a CC BY-licence.30 This means that affiliated Indigenous communities lack control over materials related to their cultural heritage and family members because these materials are available for anyone to use. To illustrate, in some cases archival photographs representing Indigenous peoples have been used as, for instance, phone covers or garments without any explicit consent or permission from the communities concerned.31 This highlights the problem of making digital materials freely available; they might end up being used in commercial activities by non-Indigenous persons or contribute to the further exoticisation of Indigenous peoples or other contexts of harmful use.

These and several other similar and related controversies have sparked discussions related to the possibilities for revising the role and key structures of the IPR system in order to meet the needs of Indigenous cultural heritage. For example, Rosa Maria Ballardini, Heidi Härkönen and Iiris Kestilä argue that this step would require a new kind of pluralistic and inclusive form of IPR.32 Indeed, one quite logical and perhaps even obvious option could be to use digital technologies to make Indigenous cultural heritage accessible in ways that respect Indigenous viewpoints. Yet most of the existing technical solutions currently in use still rely on the same IPR framework, which stands in contrast to Indigenous viewpoints. While digital technologies make access easier, they also make distribution and use quicker and, at times, uncontrollable. As such, the digitalisation of Indigenous cultural heritage should force us to take a step back and rethink the overall logic, structures and perhaps even justifications behind the IPR system in order for it to become more ethically respectful from the perspective of Indigenous peoples.

3 Methods

The theoretical analysis highlighted several gaps in the literature and identified questions and possible clashes involving legal and ethical issues governing the cultural heritage of Indigenous peoples – indeed, issues in need of further investigation. In order to deepen and contextualise our understanding of these issues, we conducted an empirical study in the form of case study research (CSR).33 Case study analysis was chosen because an in-depth investigation was needed to provide a holistic understanding of the topic under investigation, and because the legal and ethical aspects of Indigenous cultural heritage governance and IPR-related issues were, to a large extent, a “contemporary phenomenon within a real-life context”.34 In other words, an interpretative and “existential” enquiry,35 focused on participants’ subjective experiences and understanding, was required in order to examine how a new governance model and IPR legal framework more respectful towards the ethical values of Indigenous peoples in the context of cultural heritage could be achieved.

3.1 Case selection

The article is based on a “single” case study, namely the DigiSamiArchives project. This choice was taken first because the case selected was unique, incomparable to others, and particularly distinctive and notable with respect to the problems that we were considering.36 Moreover, one of the authors of this paper was involved as a researcher in the DigiSamiArchives project, thus enabling us to gain insights via her intrinsic knowledge and direct observations in terms of project developments. Indeed, the choice to use only one case study is supported by the case study research literature.37 Although the use of a single case study carries limitations, primarily the fact that it does not allow comparisons and limited generalisations, it carries a great deal of advantages as a means to both understand and explain the selected phenomena, when applied to the right context. Gustafsson argues that amongst the reasons for choosing single case studies are the context, how much is known and, especially, how much new information the cases bring.38 Indeed, in our case the latter reason was a main decision-making criterion.

Specifically, ours was an “intrinsic” case study because we had a genuine interest in the phenomenon under investigation and we wanted to better understand it. In other words, the study was not undertaken primarily because the case represented other cases or because it illustrated a particular trait or problem, or to understand some abstract construct or generic phenomenon.39 Another factor that justified use of a “descriptive” case study40 was the need to develop a comprehensive and descriptive understanding of the phenomenon concerning the interrelation between governance, law, and ethics in terms of Indigenous cultural heritage. This enabled us to understand the causes of the problems identified, the forces behind the solutions, the potential outcomes of their implementation, and their connections to relevant theories, concepts, and policies.

3.2 Selection of respondents

The selection of respondents was carried out by identifying their roles in developing the service in question. The roles we were interested in were those related to the technical development of the platform, IPR management and arrangements, and ethical guidelines. As one of the authors was closely connected to the latter two, the project’s Principal Investigator (PI) (interviewee 1) participated in interview 1 in order to answer questions related to these areas. In addition, we interviewed two respondents involved in the technical development of the platform, the leader of the technical work-package (interviewee 2), and the main contributor to the execution of the platform (interviewee 3). They also had expertise on the licences used, especially as they related to the outcomes of the project. These persons were suggested by the project PI.

3.3 Interview protocol, data collection, research questions and analysis

Studying phenomena related to the governance, IPR and ethics of Indigenous cultural heritage requires consulting multiple data sources to enable triangulation. As such, the study gathered evidence from two main sources: interviews and documents.

The documents examined included European legislation in the area of IPR and cultural heritage, descriptions of Indigenous customary laws, national legislation related to Indigenous people and some national European jurisdictions, as well as scholarly literature on the topic. In addition, observation of the structures and internal developments of the selected case under investigation was carried out by one of the authors of this paper, who, as mentioned, was also a research team member of the DigiSamiArchives project. This enabled us to enhance sources of evidence, thus improving the validity and reliability of the study.

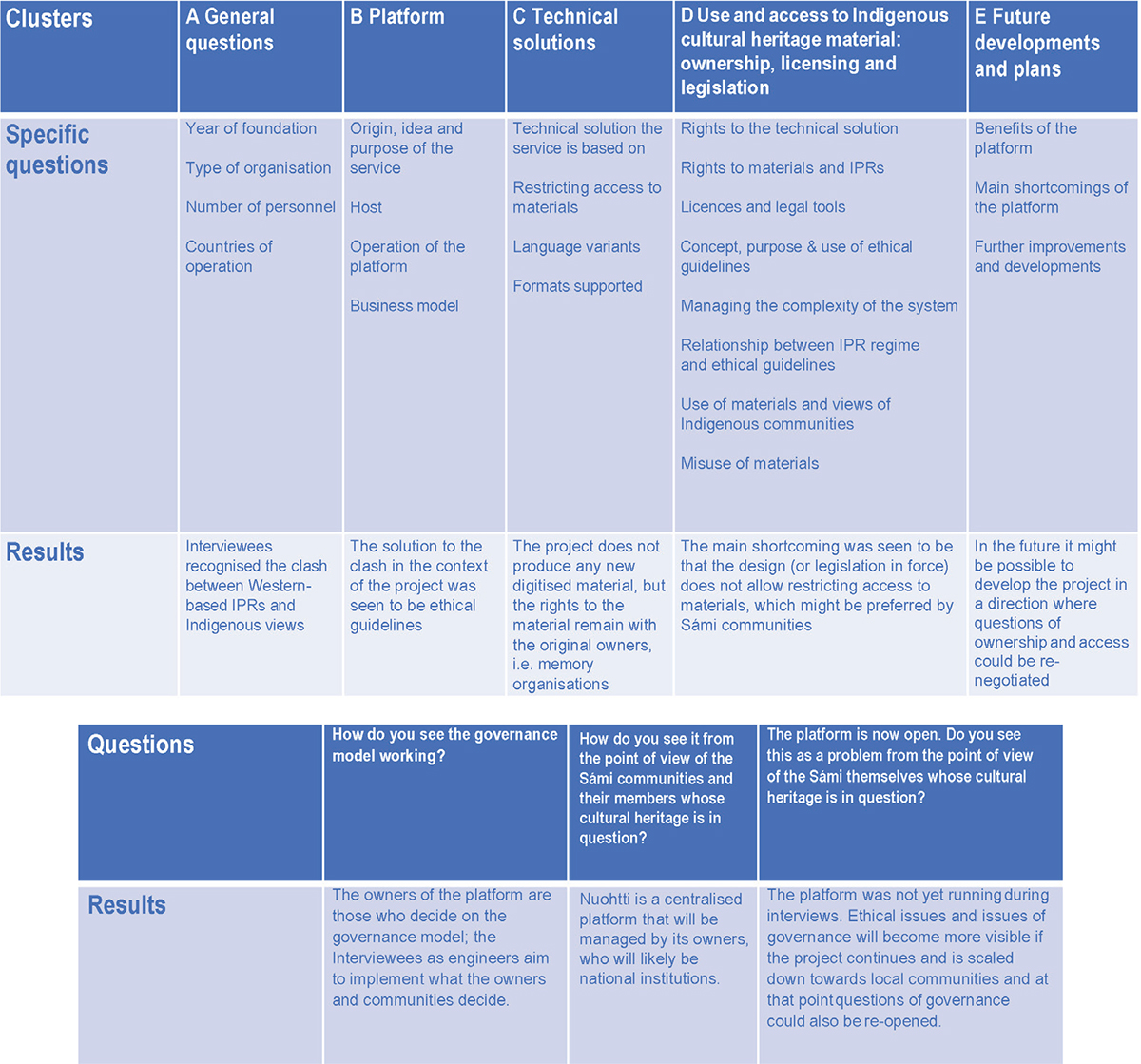

Two interviews were conducted based on two separate semi-structured interview protocols. In interview 1 (2.9.2021) we interviewed Interviewee 1, Interviewee 2 and Interviewee 3 and addressed issues related to the IPR and ethical frameworks relevant to and used in the platform developed in the DigiSamiArchives project, while in interview 2 (2.12.2021) we interviewed Interviewee 2 and Interviewee 3, focusing on questions related to the governance model used by the platform (see Appendixes I and II for a full list of questions for each of the interview protocols; the research questions posed to the respondents during the two interviews are also summarised in Table 1). The interviews were conducted online and lasted approximately one hour each.

The interviews followed the snowball sampling method,41 where two of the authors of this paper asked the questions included in the interview protocol and, when necessary, further elaborated upon them. In other words, the semi-structured nature of the interviews meant that the questions were taken as starting points for further discussion. Moreover, one researcher from our group was present as an observer, taking notes and reacting if some point was missing or needed further elaboration. As mentioned, because one of the authors of this paper was also a researcher on the DigiSamiArchives project, she did not participate in the interviews in order to avoid possible contamination of the interview results. All the interviewees were asked for their prior consent to participate as well as permission to record the interviews.

The respondents were asked to answer the interview questions from the perspective of their own discipline and expertise in the field, as well as based on their role in the DigiSamiArchiveS project. The respondents were free to propose solutions or provide other insights, as well as to corroborate evidence obtained from other sources not included in the interview protocol. This interactive approach to data collection increased the depth of the data gathered. Moreover, interviewing multiple people from the same case allowed us to triangulate their ideas, which helped in obtaining objective and reliable results.42 Overall, the case study generated new understandings rather than simply answering a few specific questions, providing a rich corpus of material for in-depth data analysis.

All respondents were consulted at least three times in line with the following process: 1) initial e-mail contact on the topic being investigated to discuss the scope of the study, present the research questions and gather initial feedback on the perception of the researchers working in the DigiSamiArchiveS project; 2) online contact to conduct semi-structured interviews with a group of selected experts from the DigiSamiArchiveS project; 3) final contact with the respondents to gather feedback on our own analysis and interpretation of the respondents’ answers, as well as to fill in any gaps. Qualitative data were collected on all occasions.

All interviews were recorded and transcribed to allow for more detailed analysis. A pattern matching analysis based on clusters was used for analysis of both interviews. As Noemi Sinkovics explains, “pattern matching involves the comparison of a predicted theoretical pattern with an observed empirical pattern.”43 Our approach could be defined as “flexible pattern matching”, meaning that “the constructs/dimensions/patterns specified a priori mostly constitute an initial tentative analytical framework aimed at providing guidance and some focus for the explorations”.44 In practice, the clusters were formed based on research questions which were formulated based on the knowledge gathered from our literature review. The concepts and theories emerging from the interviews were then compared with the existing literature and pre-defined questions.

A draft report was written based on the data obtained from the documents and interviews. Below, the answers from the interviews and the information collected from the documents are presented together, along with the researchers’ own perspectives and analysis. All respondents reviewed the report twice to enable effective triangulation,45 and improve the construct validity46 of the study.

4 Results

The discussion below is divided into two main categories that reflect the structure of the two interviews conducted and of the related interview protocols (see Appendixes I and II). Following the logic of this paper, we present firstly the second interview (on governance models) and then the more detailed IPR issues related to the structure of the platform.

4.1 The governance model

Interview 2, where Interviewee 2 and Interviewee 3 were our respondents, dealt with the governance model of the DigiSamiArchiveS platform. In accordance with our interview protocol, the interview concentrated on three questions:

– Q1: How do you see [the] governance model working?

– Q2: How do the interviewees see the governance model from the point of view of the Sámi communities and their members whose cultural heritage is in question?

– Q3: Did the interviewees see the platform being open as a problem from the point of view of the Sámi themselves whose cultural heritage is in question?

All in all, the interview lasted 44 minutes. Differently from interview 1, interview 2 was based on more open questions; thus the methodology was more conversational.

At the beginning we explained to the Interviewees what we mean by the governance model, as described above in Section 2.1. We also explained our hypothesis: that a decentralised platform could achieve self-governance sensitive to small-scale, local Indigenous communities conserving their own cultural heritage, as opposed to a traditional centralised large-scale state-led system.

At the beginning of the interview, the Interviewees reminded us that the platform was not running yet, so it was not open to the public at the time of the interview. As Interviewee 2 noted, the project would run until the end of 2021 and the platform was still under development. In addition, the negotiations on hosting the service were still ongoing. However, the Interviewees pointed out that the governance model is not affected by transferring the platform to new hosts as the material- providing organisations remain fully responsible for governing the materials that remain in their possession. As Interviewee 3 stated on the platform:

I think the governance model is unchanged here, because the material-providing organizations remain fully responsible for governing the materials that are in their possession […]. From my point of view, Nuohtti’s owners can govern Nuohtti. For example, they can make decisions on what materials to include or what [organizations] to include, but the material-providing [organizations] are actually still responsible for governing the materials, whether it is by the [organizations] themselves or in participation with the Sámi communities.

As described throughout the interview, Nuohtti is a centralised platform that will be managed by its owners, which will likely be national institutions. While these institutions – for example, Sámi Archives of Finland – closely cooperate with Sámi communities, they are not Sámi institutions per se. However, according to the interview the Sámi communities see the platform as an interesting and potential tool for them to learn more about their culture and see what has been archived from it. However, Interviewee 2 noted that issues related to ethics had also been identified.

The Interviewees envisaged that if the project is continued and new material added from outside the archives, such as from the Sámi communities themselves, a new question about the governance model should be raised regarding “indigenising” the service and possibly increasing Sámi ownership over the materials. Also, albeit no new material will be added, the material is currently made more accessible. This means that while materials can quite literally be accessed more easily in an online environment, accessibility also refers to ways in which, for example, a platform’s interface is translated into Northern Sámi and the use of automated translating tools to translate topic words from the multilingual materials to make them more searchable and discoverable using Northern Sámi and other selected languages. Thus, accessibility was not only seen as a negative issue. Interviewee 2 pointed out that, as engineers, the Interviewees saw policy and mechanisms to implement that policy as separate issues. Engineers implement the mechanisms to support different policies as widely as possible. Who decides what that policy is are the people who use the service, and obviously the owners. For example, governance of rights associated with the materials could cover the ownership of joik records. In Sámi customary law the “owner” of the joik is usually the person the joik is about, whereas in Western-based IPR systems the “owner” is the person who sang the joik. These types of issues were seen as part of the policies that the engineers would implement in the future. However, the Interviewees were of the opinion that the content of these policies should be agreed upon between the parties (namely, the owners of the service, Sámi communities, and so on).

Interviewee 2 also noted that ethical issues and issues of governance will become more visible if the project continues and is scaled down. However, so far Sámi communities have expressed considerable interest in a continuation of the project. The opportunity to include materials from outside the archives – for instance from Sámi communities has also been considered, pointing to the continued need for governance issues to be strongly present in the future, as private communities might really own the accessed materials. While both Interviewees recognised these governance issues, it was concluded that many questions remain open at the moment, as negotiations on the transfer of and possible future projects are still ongoing.

4.2 IPR and Indigenous worldviews

Interview 1 involved discussions with Interviewee 1, Interviewee 2 and Interviewee 3. The interview consisted of five sets of questions, according to our interview protocol:

– Section A): the DigiSamiArchives platform;

– Section B): the technical solutions used in the platform;

– Section C): use of and access to Indigenous cultural heritage material in terms of IPR ownership, licensing and litigation;

– Section D): Future developments and plans for the DigiSamiArchives platform.

Overall the interview lasted 63 minutes. This first interview focused mainly on RQ 2, namely: “is the clash between Western and Indigenous understandings on how CH should be accessed, protected, and used caused by the (Western-based) IPR system, vis-à-vis Indigenous peoples’ worldviews in this regard?”.

The key findings of the interview could be summarised in three clusters related respectively to:

– Cluster 1: The ways in which IPR to cultural heritage materials are arranged;

– Cluster 2: How IPR related to the technical solution used in the DigiSamiArchives platform are arranged; and

– Cluster 3: How the clash between Western-based IPR and Indigenous worldviews and ethics are negotiated in relation to IPR.

Relating to cluster 1, the ways in which IPR to cultural heritage materials are arranged, interviewee 3 explained that while the platform itself does not produce materials as such, it aggregates various collections that include Sámi cultural heritage. In practice, as explained by Interviewee 3, the platform operates so that there is a “harvester”, which allows harvesting of descriptive metadata about cultural materials from different data-providing organisations. Interviewee 3 stated that metadata is harvested either from a memory organisation’s own system, or from a cultural heritage aggregator to whom the organisation has already made the data available. Then the harvested metadata is indexed into the search engine so that a variety of searching and sorting functionalities are made available for searching the materials. Users can access the material, browse it and make different kinds of searches through an interface. In addition, some small utility tools allow users to translate topic words in the metadata into different languages, such as Northern Sámi, which can be used to geolocate places described in the metadata, so that the materials can be shown on a map. Interviewee 3 explained that as the platform only harvests material from different organisations, the IPR to such materials belong to the organisations themselves. At the moment the project only accepts materials that are “open” in the sense that they are not “access-restricted” by the organisations that provide them. The Interviewees said that normally the memory organisations that provide the data have the right to control and manage such data.

In relation to cluster 2, that is, issues related to IPR from the DigiSamiArchives platform itself, Interviewee 2 explained that all those parties who have made creations or innovations during the project would retain their IP rights. At the time of interview, though, the agreement related to IPR was in the process of being drafted. Interviewee 2 emphasised that, when the service is hosted, they do not want to interfere with the hosts and the service any longer. For instance, new hosts may want to add more archives to the service. However, Interviewee 2 also added that there was a need for the project parties to retain ownership of the research results to be used for later purposes and projects.

This discussion led to the topic of use and access to Indigenous cultural heritage material in terms of IPR ownership, licensing and litigation. This formed the core and major part of the whole interview. First – and in relation to cluster 3 on the negotiation between Western-based IPR and Indigenous views – respondents explained that the DigiSamiArchiveS platform will enable materials to be openly accessed. Because of this, the project had identified a clear need to develop ethical guidelines to guide appropriate uses of such materials, in accordance with Sámi peoples’ views. Interviewee 1 described the ethical guidelines as being a vital and integral part of the project.

Interviewee 1 then provided more context for the reasons behind the creation of ethical guidelines. Interviewee 1 affirmed that the project operates in the context of highly sensitive cultural design with histories of assimilation policies and colonialisation. For this reason, it was also considered necessary to seek preliminary approval by the Sámi institutes for all the development work in the project. For instance, when applying for project funding, support letters were requested from the Finnish Sámi Parliament, the Norwegian Sámi Parliament and also from the Swedish Sámi Parliament, who then delegated the issue to Ájtte museum, which finally signed the letter and also participated in the project steering committee.

Interviewee 1 then explained in more detail the process of creating the ethical guidelines. These were drafted by a researcher with a background in legal science and with relevant knowledge of both the legal and the ethical dimension of project activities. In practice, the work had been executed so that different existing ethical guidelines on usage of Indigenous materials had been mapped. As Interviewee 1 pointed out, the idea behind the procedure was not to develop something “from the tabula rasa”, but to take into account “what is going on elsewhere in the world”, and then tailor the guidelines so that they were usable and applicable for the DigiSamiArchives project. It was also considered vital that the ethical guidelines can be articulated in the user interface of the service. Interviewee 1 noted that the project had put a lot of effort into trying to present ethical guidelines in an accessible manner for a variety of audiences. As the Interviewees pointed out, the main purpose was that all the users of the DigiSamiArchives platform would understand that there are ethical issues related to the content hosted. For instance, Interviewee 1 explained that:

It is not appropriate to take some photo and modify it and post on social media, even though if it was legal, it’s just not appropriate, and this is what we want to make people aware of. And one of the challenges here is that when people use services on the internet for instance, you know that often there is this, like you agree on terms and conditions or there are some guidelines, and the text is just so long that people don’t read it.

In order to tackle this potential usability problem with the ethical guidelines (thus, in order to avoid users “just accepting without reading” them), the project had developed and user-tested different solutions, such as a visualisation and a quiz, in order to encourage the audience to actually read the guidelines and become aware of the possible ethical issues. However, all Interviewees acknowledged that there is no way to force people to “do the right thing” or engage with the ethical aspects. Thus, the purpose of the guidelines is more about awareness-raising and spreading information about possible ethical issues rather than enforcing certain behaviour.

Regarding potential clashes between the Western-based IPR system and Indigenous views, Interviewee 1 described the issues as follows:

I think the concerns are for instance distributing material in social media, so that’s something in today’s world which easily happens. Then in some discussions there are concerns like what about if somebody finds some old handicraft pattern or something like that, and wants to make business out of it, that kind of things have appeared in some of the concerned discussions. But then on the other hand, for instance looking at the old handicraft and the clothes and these kinds of things, they can contribute to this revitalization of the culture.

Interviewee 3 continued that these clashes are bound to happen “now that memory organisations are turning towards more openness in allowing the materials to be used more widely, so that they can gain relevance in the modern day”. For example, the Finnish Heritage Agency had made a blanket decision to open their photographic collections in high resolution with a CC BY 4 licence. In this connection, and regarding the benefits of the project, Interviewee 3 noted that the

project plan is sort of based on this concept of improved digital accessibility […] so that’s the main benefit, because of course it could be a controversial benefit in some sense. Not everyone would like the materials to be so accessible.

It was also noted that the service included certain “shortcomings”, which were mainly concerned with the design: what to design in the system and what to leave out. Interviewee 2 elaborated that:

The one basic thing could be that now the memory organisations provide to our system openly accessible data that we put together. That’s a kind of limitation. The system currently is not really designed to maintain private data collections of some [Sámi communities] or any other community, and control and restrict the accessibility and different usage rights, we don’t have that functionality. We have been discussing that and it’s really basic information system functionality. There are certainly mechanisms to be applied there if we decide to do so, but at the moment there has not been such a need because [it is] open material. But in a future project we might have these kinds of restricted community-based approaches to control the material accessibility, and also the ethical guidelines.

In terms of future developments and plans (section 4 of the interview), the Interviewees hoped that the project could improve access by the Sámi community to their own cultural heritage, which was also seen as the underlying objective of the project. Interviewee 2 explained that there had been discussions on arranging a workshop where Sámi communities would participate in brainstorming in order to identify their needs. From the technical point of view there were also several ideas. For example, Interviewee 2 explained that in the future, collections could be maintained by smaller, local communities. In addition, social media aspects were seen as interesting directions for future developments. Interviewee 2 added that, so far, they had been working with archived material only, but not contemporary materials created by communities every day. However, as noted by Interviewee 3, this could also be “very challenging from a legal perspective and ethical perspectives as well. Another issue that was raised concerned the current archive legislation in force, especially if access to materials was restricted.”

5 Discussion

This article started from the premise that there is a certain clash between Western and Indigenous understandings of how cultural heritage should be governed, protected and treated through IPR. We have approached this issue through two research questions. Firstly, we asked whether the clash between Western legal systems and the expectations of Indigenous peoples is caused by the governance models that are currently in use. Secondly, we addressed the issue based on the role of IPR in the context of this clash – especially insofar as these clashes occur in the digital environment. Based on the theoretical analysis integrated with the results of the two interviews conducted, we present the key findings, further questions and possible ways forward.

The central feature of the platform developed in the DigiSamiArchives project was that the materials are not digitalised within the project, but are harvested from different material providers. The platform merely brings these collections together. Therefore, the question of ownership rights on the original copies of materials or their digital counterparts is not straightforward. While the material providers (that is, museums, archives) usually have certain rights – including ownership – to the materials, as well as data and information featured on the DigiSamiArchives platform, the platform itself is owned (and the rights are managed) by a centralised agency (the host). In other words, the governance model – and related rights constructions – of the platform enables few possibilities for right-sharing or right-management by the Indigenous peoples to whom the heritage involved belongs in the first place, although it was noted that in one sense the platform also facilitates the possibilities for communities to review what materials have already been published. For example, the platform’s feedback box could be used to “report” inappropriate materials, which could then be withdrawn from the platform. The Interviewees also brought up the possibility to enhance, for instance, ownership rights of affiliated communities in the future by developing community-based approaches to control of and access to materials. In practice, this would mean restricting access to the materials/service in a way that only members of designated communities would be able to access the materials. However, in terms of legislation, this was seen as complicated. In that regard, for example, it was mentioned that this would not be in line with the Finnish Archives Act. Although at the time of writing this article it is still not known who will host the platform, it seems likely that ownership will be some combination of the National Archives of Finland, Sweden or Norway or even all of them together. The National Archives are public institutions in each of these countries, which means that laws about access to public documents apply. Restricting access to public documents based on ethnicity (for example, if only Sámi people could access certain documents), seems a difficult equation in the light of legislation regarding non-discrimination. In addition, one might also ask whether and to what extent widely accepted principles in IPR legislation could be changed or revised for the specific case of Indigenous cultural heritage. To illustrate, in most IPR legislation, rights to creations belong to the original creator, who could assign them to other entities. So, for example, pictures of Sámi culture belong to the person/s who took the photos (regardless of whether they belong to the Sámi community or not) or the entity to which the copyright to the photo has been assigned (such as museums or archives). Enabling possibilities for Sámi people – for instance – to restrict access to certain pictures about their culture (such as human remains) might distort the way copyright legislation functions in accordance with the well-known and accepted “neutrality” principle. Besides, IPR are not absolute but rather limited in time: for example, copyright rights expire after 70 years from the death of the author. This means that the work enters the public domain for anybody to use, share, copy, and so on. Again, any restrictions on or limitations to these principles might not only be legally unsustainable, but might eventually distort the whole function of the IPR system as a whole, creating fragmentation and ultimately uncertainty.

Indeed, it would seem that if the ownership of communities were strengthened, this would require creating new digitalised collections or transferring the rights to the communities. However, an interesting notion was presented by Interviewee 2 in relation to contemporary materials and social media aspects. That is, perhaps collections would not need to be archival collections as such, but living heritage produced by individual members of the communities, for example in a similar manner to social media platforms, where members of the communities could upload and comment on one another’s pictures and other materials. That way, restricting access to the materials might also be easier.

While the platform may in the future be scaled down closer to the communities, currently the key protection mechanism from the perspective of ethics consists of ethical guidelines. Legislative changes, especially with regard to the most fundamental principles of the system, are a slow process. Regardless, as presented above, it might be difficult to adjust legislation such as IPR to the needs of Indigenous cultural heritage. Indeed, several Indigenous peoples around the world have developed ethical guidelines for the utilisation of cultural heritage materials as well as for Indigenous research. There are also guidelines that relate to intellectual property rights and specifically to archive materials.47

As has been illustrated, an insurmountable gap appears to exist between Western-based IPR and Indigenous views. In the short term, it seems difficult to realistically tackle this challenge without incurring risks such as creating fragmentation or even distorting the whole IPR system. In the context of the DigiSamiArchives project, for example, closing this gap has been considered difficult for multiple reasons related to IPR and ownership rights, as well as to other relevant legislation. In this regard, ethical guidelines may prove to be a useful instrument. Although ethical guidelines cannot be executed in a similar manner to laws, they can be helpful in offering guidance on the views of Indigenous peoples. Moreover, many ethical guidelines have gained wide acceptance, especially in the context of research, and to a certain extent have therefore acquired unofficial binding status. Our case study clearly shows that ethical guidelines are vital for successful realisation of the DigiSamiArchives project and platform.

Another perspective might be the potential of ethical guidelines to move beyond normative conceptions of the nation state and its laws.48 Ethical guidelines can go further than legislation currently in force. For example, Rauna Kuokkanen49 touched upon the same phenomenon in relation to the Ellos Deatnu! (Long Live Deatnu!; Long Live Teno!) movement that declared autonomous an island in the Teno river (in Northern Sámi the river is called Deatnu) and the waters surrounding it, stating that instead of state law, the area is governed by customary Sámi law. According to Kuokkanen,50 “post-state Indigenous sovereignty movements reject mainstream politics” and their colonial and patriarchal institutions. For example, “Ellos Deatnu is making efforts to enact an ‘alternative’, anti-oppressive mode of Indigenous Sámi governance corresponding to central Indigenous feminist tenets”.51

Indeed, it could be argued that ethical guidelines have the potential to transform governance models that are officially defined as centralised to more decentralised and participatory forms. An interesting question, though, is whether such guidelines could go even beyond that and actually trigger creation of new “hybrid” governance models that could derive from Indigenous communities and their ontologies. There seems to be hope in this respect. For example, currently there is an ongoing process to create ethical guidelines for Sámi research. The working group organised hearings during the spring of 2022, where, in cooperation with Sámi communities, people were invited to discuss the draft guidelines.52 What can be said quite certainly is that these tools, when well designed, co-created with the parties and properly integrated into the system, can be powerful in raising global policy awareness, enhancing sensitivity on the part of researchers, developers and users in the matter, and changing peoples’ behaviour towards more respectful and ethical practices.

6 Conclusions

Indigenous peoples hold a rich diversity of cultural heritage, including practices, representations, expressions, knowledge and skills. Their heritage contributes to the ongoing vitality, strength and wellbeing of these communities, representing a cornerstone for fostering sustainability in our society, including helping protect biodiversity. Therefore, the practices used for safeguarding, transmitting and recreating this heritage should both reflect Indigenous worldviews and support participation by Indigenous peoples in shaping the heritage discourse and ensuring that their experiences and needs are taken into account.

In this article, we have discussed the single case of DigiSamiArchives. However, there is a need for future research that compares this platform with other solutions that, dissimilar to the DigiSamiArchives platform, rely on a decentralised governance model. Here, research might show whether decentralised models are able to take Indigenous perspectives better into account.

Although the challenges discussed in this article have been widely and globally recognised, and several policy measures and guidelines have been implemented over the years that embrace more inclusive and pluralistic approaches in this context, both the governance models and the legislative tools used to regulate Indigenous cultural heritage are currently still lagging behind. Our study showed both via a theoretical and an empirical analysis how the current IPR framework governing Indigenous cultural heritage is often misaligned with Indigenous ethics. Yet at the same time we also shed light over possible short-to-medium term solutions, primarily via integrating the existing rules with norms and customs, such as ethical guidelines that are co-created by, with, and for Indigenous communities. Regardless of their non-binding nature, these tools can be highly effective and provide much more agile frameworks for inclusiveness. Indeed, the long-term ambition of further developing the IPR legal system towards more plurivocal and sustainable constructions is not to be forgotten. It will take time to trigger the necessary change in IPR legislation, but at the end of the day “our patience will achieve more than our force”, as Edmund Burke once said. We shall wait vigilantly.

NOTES

- 1. Principles for Responsible and Ethically Sustainable Sámi Tourism (Sámi Parliament in Finland, 2018), 4, https://www.samediggi.fi/ethical-guidelines-for-sami-tourism/?lang=en (accessed 4 April 2023).

- 2. Jelena Porsanger and Pirjo Kristiina Virtanen, “Introduction – a holistic approach to Indigenous peoples’ rights to cultural heritage,” AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples 15, no. 4 (2019): 291, https://doi.org/10.1177/1177180119890133

- 3. Rauna Kuokkanen, “The Deatnu Agreement: A Contemporary Wall of Settler Colonialism,” Settler Colonial Studies 10, no. 4 (2020), https://doi.org/10.1080/2201473X.2020.1794211

- 4. See e.g. Rosa Ballardini, Heidi Härkönen and Iiris Kestilä, “Intellectual Property Rights and Indigenous Dress Heritage: Towards More Social Planning Types of Practices via User-Centric Approaches” in Legal Design: Integrating Business, Design and Legal Thinking with Technology, ed. Marcelo Corrales Compagnucci, Helena Haapio, Margaret Hagan and Michael Doherty (Edward Elgar, 2021).

- 5. Edward Said, Orientalism (Pantheon Books, 1978).

- 6. Laura Junka-Aikio, “Can the Sámi Speak Now? Deconstructive Research Ethos and the Debate on Who Is a Sámi in Finland,” Cultural Studies 30, no. 2 (2016): 217, https://doi.org/10.1080/09502386.2014.978803

- 7. Kathy Bowrey and Jane Anderson, “The Politics of Global Information Sharing: Whose Cultural Agendas Are Being Advanced?,” Social & Legal Studies 18, no. 4 (2009): 480, https://doi.org/10.1177/0964663909345095

- 8. Suomen perustuslaki [Finnish Constitution] 731/1999.

- 9. Grazia Borrini-Feyerabend and Rosemary Hill, “Governance for the Conservation of Nature” in Protected Area Governance and Management, ed. Graeme L. Worboys, Michael Lockwood, Ashish Kothari, Sue Feary and Ian Pulsford (ANU Press, 2015): 171.

- 10. Sam Grey and Rauna Kuokkanen, “Indigenous Governance of Cultural Heritage: Searching for Alternatives to Co-Management,” International Journal of Heritage Studies 26, no. 10 (2019): 8, https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2019.1703202

- 11. ibid.

- 12. ibid.

- 13. Elinor Ostrom, Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action (Cambridge University Press, 1990).

- 14. Jose Apesteguia and Frank P Maier-Rigaud, “The Role of Rivalry: Public Goods Versus Common-Pool Resources,” Journal of Conflict Resolution 50, no. 5 (2006), https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002706290433

- 15. The Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage adopted by the UNESCO General Conference on 17 October 2003.

- 16. Apesteguia and Maier-Rigaud, “The Role of Rivalry”.

- 17. James M Buchanan, “An Economic Theory of Clubs,” Economica 32, no. 152 (1965), https://doi.org/10.2307/2552442

- 18. Garrett Hardin, “The Tragedy of the Commons,” Science 162, no. 3859 (1968).

- 19. Ostrom, Governing the Commons.

- 20. OMC, “Participatory Governance of Cultural Heritage”. Report of the OMC (Open Method of Coordination) Working Group of Member States’ Experts (Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2018), https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/b8837a15-437c-11e8-a9f4-01aa75ed71a1 (accessed 4 April 2023).

- 21. Grey and Kuokkanen, “Indigenous Governance of Cultural Heritage,” 7.

- 22. Ibid., 8.

- 23. William Fisher, “Theories of Intellectual Property” in New Essays in the Legal and Political Theory of Property, ed. Stephen Munzer (Cambridge University Press, 2001); Kamrul Hossain and Rosa Maria Ballardini, “Protecting Indigenous Traditional Knowledge Through a Holistic Principle-Based Approach,” Nordic Journal of Human Rights 39, no. 1 (2021); Konstantinos Alexandris Polomarkakis, (2020). “The European Pillar of Social Rights and the Quest for EU Social Sustainability,” Social & Legal Studies 29, no. 2. (2020), https://doi.org/10.1177/0964663919829199

- 24. Larissa Katz, “Exclusion and Exclusivity in Property Law,” The University of Toronto Law Journal 58, no. 3 (2008); Grey and Kuokkanen, “Indigenous Governance of Cultural Heritage”.

- 25. Antony Taubman, “Indigenous Innovation: New Dialogues, New Pathways” in Indigenous Peoples’ Innovation. Intellectual Property Pathways to Development, ed. Peter Drahos and Susy Frankel (Anu Press, 2012): 16.

- 26. See, for example, Sámi Parliament in Finland, “Principles for Responsible and Ethically Sustainable Sámi Tourism,” 7; Tuomas Mattila, “Saamelaisten tarpeet henkisen omaisuuden suojaan tekijänoikeussuojan ja tavaramerkkisuojan näkökulmasta – erityisesti duodji-käsityön ja saamenpuvun osalta,” Opetus- ja kulttuuriministeriö 11.12.2018: 32.

- 27. Mikko-Pekka Heikkinen and Jussi Pullinen, ”Disney kävi Inarissa tutkimassa saamelaista elämää Frozenin jatko-osaan – Saamelaiset haluavat korvausta,” Helsingin Sanomat, September 23, 2016, https://www.hs.fi/kotimaa/art-2000002922271.html; Ballardini, Härkönen and Kestilä, “Intellectual Property Rights and Indigenous Dress Heritage”.

- 28. First Archivist Circle, “Protocols for Native American Archival Materials,” (2007) https://www2.nau.edu/libnap-p/protocols.html (accessed April 4 2023).

- 29. “The British Museum Puts 1.9 Million Works of Art Online,” Open Culture, accessed April 4, 2023, http://www.openculture.com/2020/04/the-british-museum-puts-1-9-million-works-of-art-online.html

- 30. “Museovirasto avaa yli 200 000 kokoelmakuvaa painolaatuisina vapaaseen käyttöön”, Finnish Heritage Agency, accessed April 4 2023, https://www.museovirasto.fi/fi/ajankohtaista/museovirasto-avaa-yli-200-000-kokoelmakuvaa-painolaatuisina-vapaaseen-kayttoon

- 31. See, for example, Linda Tammela, “Edesmenneen isoäidin kasvot päätyivät amerikkalaisnettikaupan leggingseihin – näin voi käydä sinullekin, sillä kuvia on julkaistu laajalla lisenssillä,” YLE, June 18, 2021, https://yle.fi/uutiset/3-11965453

- 32. Ballardini, Härkönen and Kestilä, “Intellectual Property Rights and Indigenous Dress Heritage”.

- 33. Robert K Yin, Case Study Research: Design and Methods (Sage Publications, 2013).

- 34. Ibid.

- 35. Jack Meredith, “Building operations management theory through case and field research” Journal of Operations Management 16 (1988): 441–454.

- 36. Bent Flyvbjerg, “Five misunderstandings about case-study research. Qualitative Inquiry 12(2) (2006): 219–245.

- 37. See e.g. Yin (2013), note 33, pp. 1–15.

- 38. J. Gustafsson, “Single case studies vs. multiple case studies: A comparative study” (2017), available at: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Single-case-studies-vs.-multiple-case-studies%3A-A-Gustafsson/ae1f06652379a8cd56654096815dae801a59cba3

- 39. Stake, The Art of Case Study Research.

- 40. Meredith, “Building operations management theory”.

- 41. Leo A. Goodman, “Snowball sampling” Annals of Mathematical Statistics 32 (1961): 148–170, https://doi.org/10.1214/aoms/1177705148

- 42. Michael Quinn Patton, How to Use Qualitative Methods in Evaluation (Sage Publications, 1987).

- 43. Noemi Sinkovics, “Pattern matching in qualitative analysis” in The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Business and Management Research Methods, ed. Catherine Cassell, Ann Cunliffe and Gina Grandy (Sage Publications, 2018), 468–485.

- 44. Ibid., 476.

- 45. Meredith, “Building operations management theory”.

- 46. Chris Voss, Nikos Tsikriktsis and Mark Frohlich, “Case research in operations management”. International Journal of Operations & Production Management 22 (2002): 195–219.

- 47. See, for example, First Archivist Circle, Protocols for Native American archival materials (2007), https://www2.nau.edu/libnap-p/protocols.html (accessed 21 September 2022); Margaret Orr, Peter Kenny, Isobel Nampitjinpa Gorey, Topsy Dixon, Alma Mir, Emily Cox and Joni Wilson, Aboriginal Knowledge and Intellectual Property Protocol: Community Guide (Desert Knowledge Cooperative Research Centre, 2009).

- 48. Rauna Kuokkanen, “Ellos Deatnu and post-state indigenous feminist sovereignty” in Routledge Handbook of Critical Indigenous Studies, ed. Brendan Hokowhitu, Aileen Moreton-Robinson, Linda Tuhiwai-Smith, Chris Andersen and Steve Larkin (Routledge, 2021), 310–323.

- 49. Ibid.

- 50. Ibid., 319.

- 51. Ibid, 318.

- 52. University of Lapland, Saamelaisia koskevan tutkimuksen eettiset ohjeet [Ethical guidelines on research of Sámi], https://www.ulapland.fi/FI/Kotisivut/Saamelaisia-koskevan-tutkimuksen-eettiset-ohjeet- (accessed 21 September 2022).

Appendix I / Interview I

Interview Protocol

Overall theme of the interview: We are interested in the ways in which use and access to Indigenous cultural heritage materials can be enabled through technical solutions. Our focus is especially on questions of ownership, distribution and ethical aspects of use.

Please find below the specific themes we are hoping to discuss during the interview. The interview will last about 45 minutes. We wish to record the interview, with your consent. We are not expecting your organization to provide us with any confidential information.

A) General questions

Basic information on the organization:

• Year of foundation

• Type of organization

• Number of personnel

• Countries of operation

B) Platform (7 min)

1. Could you describe shortly the origin, idea and purpose of your service?

2. Who hosts the service?

3. Could you describe how your platform operates in practice?

4. What is your business model? If this is not for profit: how is your work supported (and what kind of agreement/commitment do you have with the bodies that finance you)?

C) Technical solutions used (7 min)

5. Could you describe shortly the technical solution your service is based on?

6. Does the platform /technical solution allow restricting access to the material that is hosted? If not, why? If yes, are there any legal challenges with such restrictions?

7. Are different language variants supported by your technical solutions?

8. What kind of file formats are supported?

D) Use and access to Indigenous cultural heritage material: ownership, licensing and legislation (20 min)

9. Who owns the rights on the technical solution?

10. Who owns the rights to the material displayed?

11. What intellectual property rights the materials are subject to?

12. What licenses or legal tools are used by the platform to provide access to the material it hosts?

13. Your service features ethical guidelines? Can you describe the concept, purpose and use of ethical guidelines in your platform?

14. We understand that the ethical guidelines are developed based on the principles and views of the Indigenous communities involved. However, different communities may have different views on these issues. Does this make the system complex? If yes, how is this complexity managed?

15. What is the relationship between the IPR regime and the ethical guidelines used in your platform?

a. For e.g. if the ethical guidelines are based on customary law of the Indigenous communities at stake, while the licenses rely on western/state IPR legislation, do you see any challenge?

b. In case of a conflict (e.g. between customary law of the Indigenous communities at stake and western/state IPR legislation) related to the use of the service or the materials uploaded in your platform, what would be the applicable legal principles?

16. What kind of measures have you taken to ensure that the uploaded material cannot be downloaded, further shared or even further modified in ways which would be against the community’s views?

17. Is there any other measure that you have taken in order to combat misuse of the Indigenous cultural heritage material that is uploaded in your platform?

E) Future developments and plans (10 min)

18. Can you briefly summarise what are the main benefits of your platform?

19. Can you briefly summarise what are the main shortcomings?

20. Do you have plans for how to further improve or develop your service in the future? Elaborate.

Appendix II / Interview II

Interview Protocol

Overall theme of the interview: We are interested on the governance model of the Digital Archive.

By governance model we mean governance of the intangible cultural heritage in digital form. We see cultural heritage as a common-pool resource: property rights to cultural heritage are not explicitly defined (in Western legal meaning) but they can be appropriated by private actors. The traditional solution for governance of common-pool resources has been privatisation. However due to the communal nature of cultural heritage, privatisation has led to appropriation and exploitation by economic actors. Conventionally, exploitation has been tried to be prevented by regulation and state ‘ownership’. An alternative solution is a voluntary and participatory self-governance by local communities directly affected by the resource as cultural heritage.

Our hypothesis is that from an economic point of view, a decentralised platform can achieve a self-governance sensitive to small-scale local Indigenous communities conserving their own CH instead of a traditional centralised large-scale state-led system.

Please find below the specific themes we are hoping to discuss during the interview. The interview will last about 45 minutes. We aim at using the clusters of questions below as a starting point for the interview and go into more detailed questions if necessary (snow-ball approach). We wish to record the interview, with your consent. We are not expecting your organization to provide us with any confidential information.

Question 1:

The cultural heritage images are governed by Museovirasto. Digital Access to the Sámi Heritage Archives is a project by Kansallisarkisto and its Sámi arkiiva, and the Norwegian Arkivverket and its Sámi arkiiva, to develop a search portal for searching Sámi cultural information from different European digital archives.

How do you see this governance model working?

Question 2:

How do you see it from the point of view of the Sámi communities and their members whose cultural heritage is in question?

Question 3:

The platform is now open. Do you see this problem from the point of view of the Sámi themselves whose cultural heritage is in question?