1. Introduction

The increasing attractiveness and accessibility of the Arctic have resulted in an expansion of tourism activities both on land and at sea. The expansion of tourism in terms of magnitude, types of activities, and impacts has occurred unevenly across the Arctic.1 Moreover, Arctic tourism is influenced by multiple factors, such as climate change; tourism governance structures, including strict environmental regulations; recent travel restrictions due to the Covid-19 pandemic; and a rapidly changing geopolitical context. In this article, we examine one such factor, tourism-related regulations, for one significant Arctic destination, the Svalbard Archipelago. Svalbard was selected for this study because of tourism operators’ clear focus on sustainability and a policy ambition to make it the best-managed wilderness area in the Arctic.2 Moreover, compared to many other remote Arctic destinations, Svalbard is easily accessible year-round due to favorable ice conditions; it also has better-developed search and rescue (SAR) facilities and harbor infrastructure.

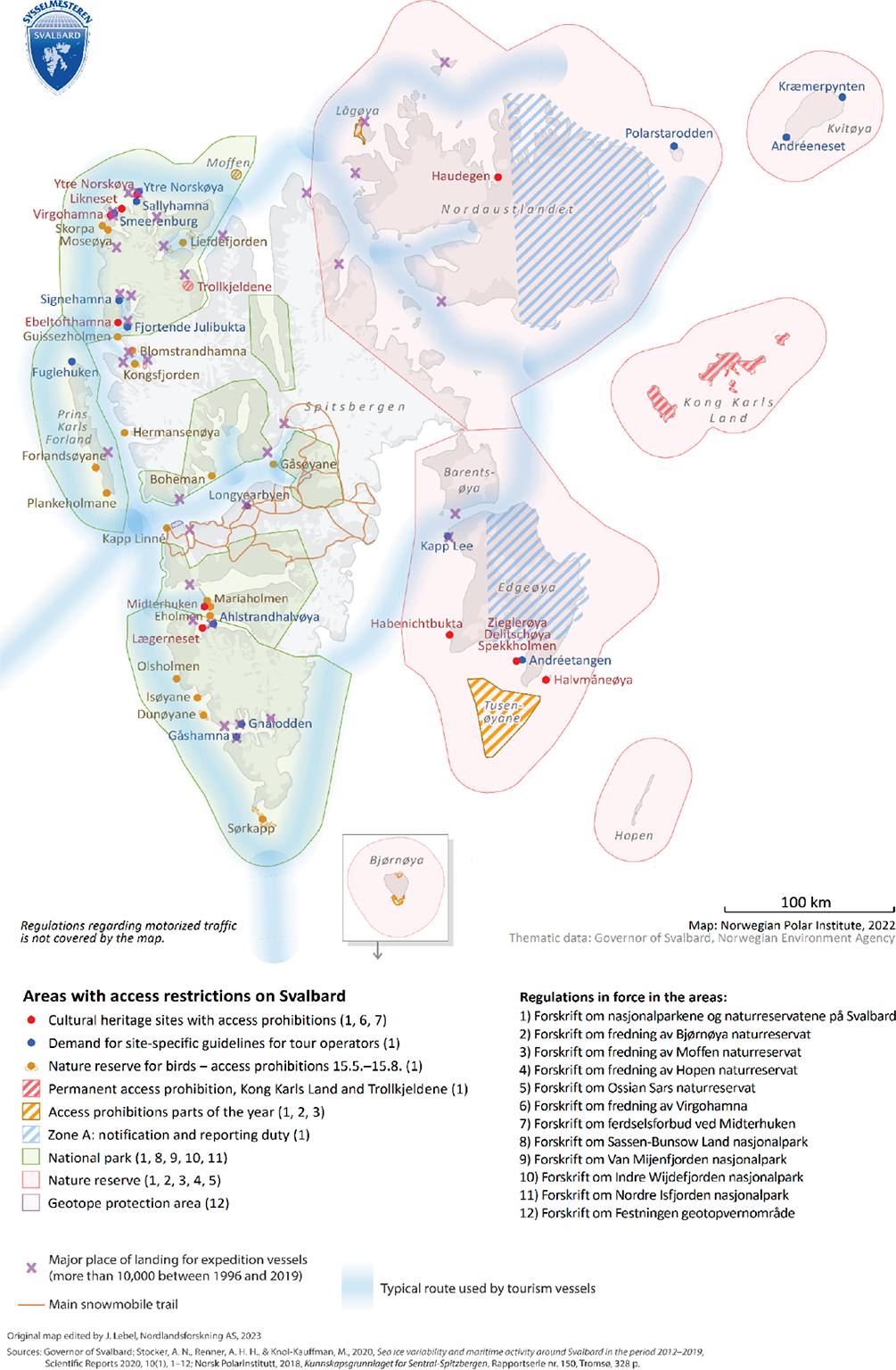

The key objectives of Norwegian Svalbard policy comprise the enforcement of sovereignty, the proper observance of the Svalbard Treaty,3 the maintenance of peace and stability, the preservation of nature, and the maintenance of Norwegian communities in the Archipelago.4 The last two points are particularly relevant. The Norwegian communities in the Archipelago are supported by facilitating the development of several industries (including a fast-growing tourism industry) and providing subsidies. Simultaneously, tourism development in Svalbard depends on preserving the pristine and vulnerable Arctic environment. Environmental protection was proposed as a goal even before the Svalbard Treaty was signed in 1920, and a new environmental regime with implications for the tourism industry emerged in the 1970s. Today, 65% of Svalbard’s land area and 87% of its territorial waters are protected (Fig. 1)5 by legislation and regulations. These regulations are the target of our review.

The lack of adequate management tools to cope with the increase in Arctic tourism, as well as the severe effects of climate change, competing geopolitical interests, and developments in resource exploitation are often highlighted in the literature.6 Svalbard illustrates the inherent potential conflict between the demand for increased tourism and strict environmental regulations intended to protect nature and limit emissions from human-related activities.7 These tensions have increased in recent decades as the archipelago has undergone a transition to use tourism, research, and education to facilitate a sustainable economic and social future. In the initial stages of this transition, a coordinated environmental policy was needed to cope with the growing pressure that tourism and resource exploitation exerted on the natural environment.8

Broader regulations intended to control the flow of visitors, protect nature, and balance residents’ interests have been promoted as necessary tools to manage the development of tourism in Svalbard.9 As Hagen et al. argued, site-specific and evidence-based management of tourism activities is needed and should involve local stakeholders.10 Because Longyearbyen is a central transit point in the Archipelago, the community experiences dilemmas regarding the flow of tourists, which stresses the environment but also brings job opportunities.11 Local infrastructure is affected by major environmental changes; close monitoring and coastal protection12 are needed alongside adequate regulations to balance strict environmental protection and the ability of local planners to establish housing in new, safer areas.13

Management policies, regulations, and practices frame the action space for tourism. The concepts of sustainable or responsible tourism are qualitative framings, i.e., ways to articulate the ethical concerns and desirable values associated with tourism. However, these concepts provide few to no specific instructions about how tourism should develop and be conducted in concrete settings. Defining the action space for future tourism in Svalbard will require stakeholders to assess the opportunities and limitations of the regulatory framework, evaluate market dynamics, and make some key political decisions about desirable tourism segments and products in the Svalbard context.14 This paper contributes to clarifying and defining the opportunities and limitations of the regulatory framework and identifies inconsistencies and potential conflicts within it. An interesting nexus of inconsistencies and conflicting interests emerges within the complex regulatory framework that calls for both sustainable tourism and wilderness conservation in Svalbard. This analysis is also relevant regarding other forms of resource exploitation in the Arctic, and in connection with how we define the space that society and actors may use to negotiate their specific challenges.

2. Framing Svalbard Tourism

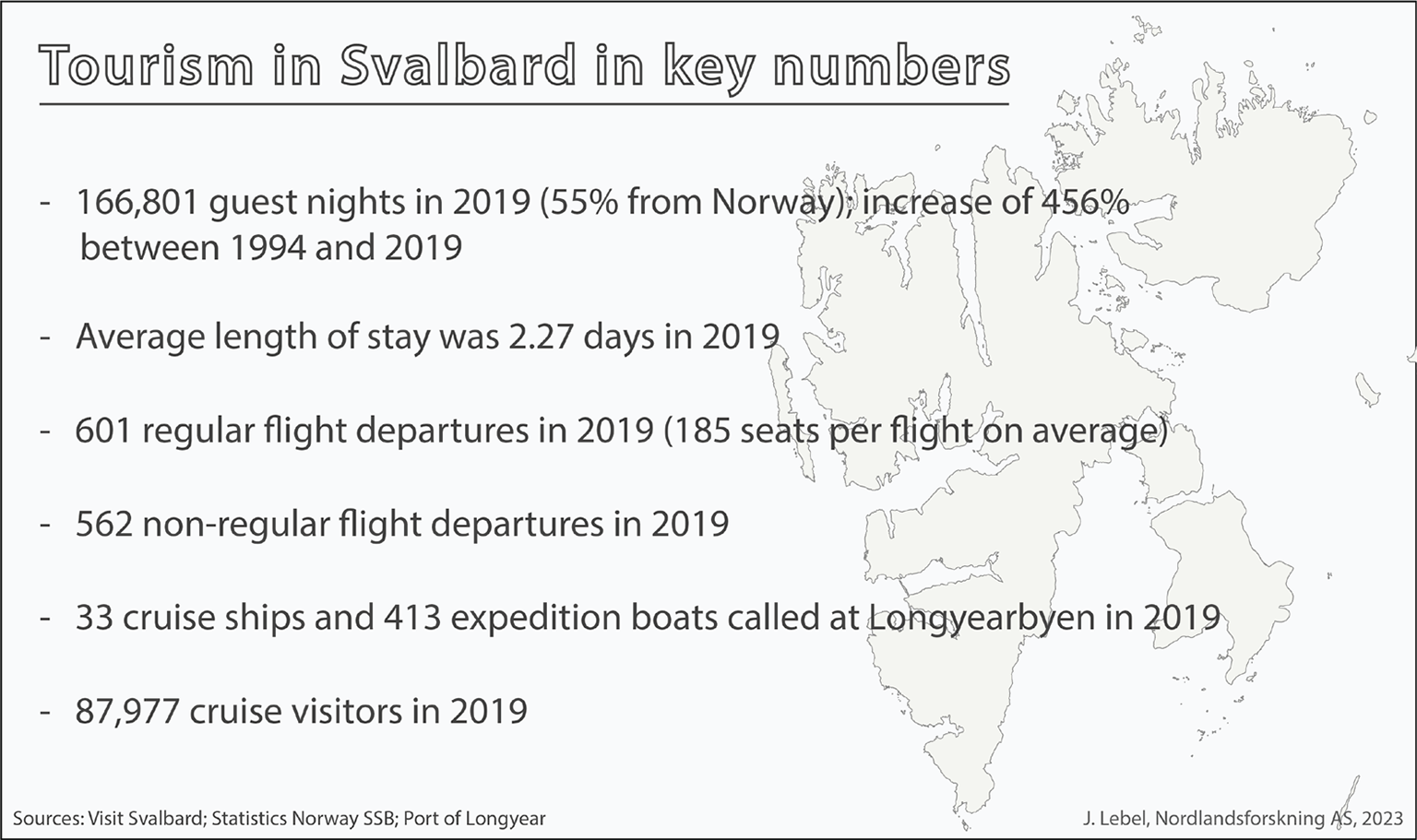

The Svalbard Archipelago has been an attractive cruise destination since the end of the 19th century.15 The strategic development of the tourism industry started in the 1970s and 1980s after the Longyearbyen airport opened in 1975 and the cornerstone coal company Store Norske was restructured. This restructuring resulted in the establishment of the tourism enterprise Info-Svalbard, now Visit Svalbard,16 in 1991. These events are important milestones, enabling the transition of the Norwegian presence on the Svalbard Archipelago17 from a coal-dominated community toward a more diversified economy that incorporates tourism, research, and education.18 The number of tourists, port calls, tourism enterprises, and employees has increased rapidly since the 1990s (Fig. 2).19

The backdrop for this study is the acknowledgment that the rapidly increasing number of Arctic tourists has both negative and positive impacts on nature and society. While various governments have roles to play in mitigating potential damage, we show that the action space for the tourism operators must also be considered in the context of national and international regulations. As in other destinations, managing tourism in Svalbard is a case of multilevel governance. Any public or private industry decision regarding the development of tourism must consider international obligations, national policies, and local needs and concerns. The relevant regulations range from supra-national strategic concerns to detailed, concrete actions in Svalbard controlled at both the national and local policy levels. Multilevel governance in the polar regions addresses three complex, interrelated themes: the interplay between management sectors, the influence of global institutions on local or regional regimes, and how nations and other actors pursue their interests within the complexities of these institutions.20 While multilevel governance is widely recognized as necessary to solve interconnected environmental and social issues,21 different theories of what constitutes multilevel governance have arisen. Two broad theoretical directions characterize the field: multilevel governance as a theory of state transformation, and multilevel governance as a theory of public policy.22 We adopt the perspective that multilevel governance is fundamentally about the capacity to address effectively a specific challenging condition.23 The Arctic demonstrates a type of multilevel governance built on institutional cooperation and collaboration rather than challenging territorial interests.24

In the 1970s, the Norwegian government evaluated the opportunities for tourism and concluded that it should be developed with a limited scope. More precisely, the white paper from 197525 states that, “It will probably not be in the interest of Norway to turn Svalbard into a typical tourism destination, since conservation interests will be threatened and because the economic benefits of tourism in Svalbard will be limited.” The following white paper (1985–1986) suggests measures to facilitate small-scale, controlled, and varied tourism that is environmentally sound and economically efficient.26 To diversify economic activities, the white paper from 1990 encourages tourism development on Svalbard but underlines that tourist activities should be regulated27 to avoid threatening the distinctive wilderness. Regulations should consider safety, the environment, and cultural heritage protection while facilitating tourism development.28 The white papers from 1985 and 1990 provide guidelines for environmental protection, while the white paper from 1994–199529 addresses the value of the wilderness and the impacts of increased infrastructure, tourism, and traffic.

The white paper from 1999–200030 emphasizes that the tourism industry should contribute both directly and indirectly to local employment, but expresses concern that tourism growth may occur more rapidly than anticipated. As a result, the government revised the management plan for tourism. The most important environmental legislation, the Svalbard Environmental Protection Act of 2001 (SEPA),31 primarily seeks to safeguard the wilderness. To limit the tourism industry’s effects, the 2007–2008 white paper32 introduces ecotourism and suggests extending tourism activities beyond the high tourism season. It emphasizes that “the traffic is also greatest in the spring and summer when the environment is at its most vulnerable … [Hence], it is necessary to control the traffic in accordance with the value and vulnerability of the various areas and their conservation goals”.33 Finally, the most recent white paper (2015–2016), suggests facilitating more local jobs in tourism by making Longyearbyen and the surrounding inhabited locations (i.e., Management Area 10) more attractive.34 In September 2021, the Norwegian government opened a broad hearing process and suggested amendments to the SEPA and associated regulations.35 The proposed changes signal increased state control,36 and the process resulted in significant reactions from Longyearbyen business operators, the local population,37 and others. The form of the new regulations after the evaluation of responses to the hearing remains undetermined.

In addition, the consequences of climatic and environmental changes present a need to limit the flow and impact of visitors, while, paradoxically, increasing the attraction of the Arctic38 as a last-chance destination. Although their impact on the environment is potentially high, tourism activities are also crucial for sustaining local communities. Studies on cruise tourism in the Canadian Arctic, for example, indicated the social, economic, and cultural opportunities that derive from a steady flow of visitors.39 However, they also emphasize many challenges and emphasize the need to improve tourism policies to consider both the benefits and risks40 alongside the importance of “site guidelines and behavior guidelines”.41 Similar challenges and opportunities are relevant in the Russian Arctic, where the implementation of a communication model to enhance cooperation between the involved cross-scale stakeholders is suggested as one of the solutions to ensure sustainable tourism.42

Sustainable tourism is closely linked to sustainable development, in that it posits that tourism-related activities should not contribute to the loss of natural resources or damage the environment, should contribute to the quality of life in local communities, and, finally, should ensure economic stability for host communities.43 In the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, the United Nations listed 17 main goals and 169 targets to promote prosperity and reduce inequality. Tourism activities are briefly mentioned in some of the targets.44 The tourism sector has mainly addressed criticism of the consequences of directing large numbers of visitors to small communities that are often located in fragile environments, but has also engaged with other issues, including emissions from transport, particularly aviation and cruise traffic. The latter is particularly relevant to Svalbard tourism.

3. Methods

We apply document analysis as a research method to reveal and understand inconsistencies and conflicting interests regarding the development of Svalbard tourism. Document analysis can be described as a systematic procedure for reviewing, examining, and interpreting documents to gain understanding, verify findings from earlier research, and produce empirical knowledge on a particular topic.45 The document analysis process includes the following main stages: document selection, appraising or making sense of the data, and synthesis.46

This study is one outcome of a partner project that applies a knowledge co-production approach.47 For the first two stages of the document analysis, we consulted with our tourism industry partners. The insights from tourism operators were crucial for identifying the criteria for document selection (Table 1). This was necessary to shorten the list of available regulatory documents to analyze. Second, our industry partners were involved in appraising and selecting the themes for the analysis. This broadened both the understanding and the scope of the analysis. The inclusion of industry partners’ knowledge and their involvement in defining the scope and content of the analysis increased the researchers’ understanding of the regulatory landscape.

| Criteria | Specification | Justification |

|---|---|---|

| Type of regulations | International, regional, and national | International, issued by IMO; regional agreements; and national legislation, issued by Norwegian ministries. |

| Focus | Relevant for tourism | Regulations that directly affect the scope of maritime and onshore tourism activities on Svalbard. |

| Timeline | 1973–2021 | The first major environmental regulation for Svalbard was issued in 1973. MARPOL was adopted in 1973.

Changes to the existing environmental regulations for Svalbard starting in September 2021 are not included in this review. |

| Language | Norwegian and English | Many of the Norwegian laws and regulations are issued in the Norwegian language only. Few of them are translated into English. International conventions and agreements are available in English. |

| Relevance check by tourism partners | Secured by Visit Svalbard and the Association of Arctic Expedition Cruise Operators | The document selection process and codes for analysis. |

We analyze two sets of laws and regulations. The first set comprises Norwegian regulations that are relevant to Svalbard tourism and are available on the Governor of Svalbard website. The second set includes relevant international policy instruments that have synergistic vertical effects through a policy chain connected to the existing environmental governance regime on Svalbard. These comprise regulations issued by the International Maritime Organization (IMO), and regional agreements (the Arctic Council). In total, our analysis includes 28 national (n = 23) and regional and international (n = 5) regulatory documents (Appendix 1). White papers issued by the Norwegian government (1970s–2010s) to direct future legislation are reviewed for contextual purposes and are not included in the analysis.

The selected national regulations and laws are thematically analyzed (a form of pattern recognition through coding analysis) with the assistance of the qualitative data analysis software NVivo.48 The analysis is interactive as the themes (codes) can be reconfigured throughout the process. By focusing on factors that frame tourism-related practices, a set of predetermined codes was developed together with our tourism industry partners. The following codes are applied for our analysis of national regulations in NVivo: nature considerations, access to land, passage (restriction, motor traffic at sea, off-road motorized traffic, individual passage), requirements for tour operators (equipment, guides, insurance, rules for establishing permanent camps, permits, and reporting), fees and taxes, sanctions and punishments, and the Governor’s role. Regional and international documents were retrieved from the relevant websites (IMO and the Arctic Council) and were analyzed using Atlas Ti software and the codes that were developed in the analysis of national documents. The following section will present our policy document analysis findings based on those categories.

4. Findings

4.1. Nature and environmental considerations

The main principle of environmental considerations is described in the SEPA’s overall purpose:49 “to preserve a virtually untouched environment in Svalbard with respect to continuous areas of wilderness, landscape, flora, fauna, and cultural heritage.” Here, we highlight three main principles that outline the environmental considerations that are related to tourism development: the duty of care, protected areas, and general principles that are applied to all species of flora and fauna.50

The duty of care and general principles pertain to any person staying or operating in Svalbard. “Consideration and caution are required to avoid unnecessary damage or disturbance of the natural environment and cultural heritage,”51 which are both important tourism products. In particular, four practices are crucial for tourism: i) exercising the precautionary principle when inadequate information about the effects of an activity is available; ii) assessing the cumulative environmental effects an activity has on the natural environment and cultural heritage; iii) user-pays principle; and iv) using environmentally sound technology to put the least possible pressure on the environment (including replacing damaging chemical and biotechnological products with others that are less harmful).

The principles of protected areas stipulate: i) including the full range of habitats and landscape types, ii) helping maintain areas of special value, iii) protecting marine and terrestrial ecosystems, and iv) contributing to maintaining wilderness.52 There are three types of protection (Fig. 1): i) National Parks, which are to be protected from any damaging activity, such as development, construction, and pollution, and access and passage that may affect or disturb the environment or cultural heritage; ii) Nature Reserves, which may be designated as untouched areas, given absolute protection, and may receive provisions for cultural heritage; and iii) protected biotopes and geotopes, which are to be protected from activities that affect or disturb their flora, fauna, distinct geological formations, or cultural heritage. In addition to protected areas, all structures, sites, and movable historical objects from before 1946 are automatically considered cultural heritage and protected with a security zone of 100 meters.53

General principles and provisions pertain to all flora and fauna on land and in the sea. Flora and fauna are to be managed to maintain the species’ natural productivity, diversity, and habitats. The principle of general protection states that “all species of flora and fauna, including their eggs, nests and lairs, are protected unless otherwise provided by this Act”.54 Two factors that are related to the protection of flora and fauna are relevant to this analysis: i) the release and transport of new species to Svalbard, relocation of indigenous species, or cultivation of species is prohibited; ii) no person may damage or remove flora, nor hunt, capture, injure, or kill fauna or damage eggs, nests, or lairs. Disturbing or exposing polar bears to danger or exposing humans to danger from them by pursuing or attracting the bears is prohibited.

Regulations pertaining to pollution, waste, and clean-up operations after an activity are relevant to tourism. Operators must clean up after an activity, and if damage to the environment is expected after the activity has ended, the Governor must be notified. Specific sections of the regulations pertain to pollution from ships and include prohibitions against possessing or initiating anything that may cause pollution. This includes releasing persistent, bio-accumulative, and toxic substances, discharging wastewater, and dumping or incinerating waste. The polluter must clean up any accidents and report them. Waste cannot be left outside planned land-use areas, and it must be stored to avoid spreading.

4.2. Area access and passage

The main principles for area access and passage are described in the SEPA and the regulations relating to motorized traffic.55 The following factors frame passage and access to certain areas: type of protection, users, and traffic.

As described above, protected areas and acceptable levels of impact from traffic and passage can be divided into three zones: national parks, natural reserves, and protected biotopes, geotopes, and cultural environments. In the remaining areas, such as Management Area 10, the level of accepted impact is higher. Furthermore, the regulations for protected areas comprise several types of passage restrictions, including seasonality, modes of transport, and geographical localities. For example, access to some nature reserves (bird reserves) is prohibited from May 15 to September 15. It is illegal to go ashore or roam within the demarcated areas around protected cultural heritage sites.56 In some areas, such as Midterhuken in Bellsund, disembarkation and land traffic are prohibited year-round. In other areas, such as the Festningen geotope protected area and in National Parks, bicycles and motorized off-road vehicles are prohibited on thawed and snow-free ground, as is landing an aircraft, flying closer than one nautical mile from a concentration of marine mammals and birds, and “overflight of the areas above at altitudes below 300 meters and out to one nautical mile from land”.57

These areas are regulated according to the type of user as well, e.g., permanent residents and visitors to the site. Permanent residents have greater access to land areas, passage,58 and harvesting59 activities on Svalbard than visitors. For example, permanent residents are allowed to use snowmobiles in significantly larger areas than visitors are.60 Visitors may use snowmobiles in some areas when accompanied by permanent residents. Individual non-resident travelers and research and educational institutions must report the field and tour arrangements outside Management Area 10 and must have insurance or financial guarantees for travel. Individual travelers who are permanent residents must report tour arrangements that involve traffic to or within national parks and nature reserves.

Area access also depends on the type of traffic (non-motorized or motorized) and means of transportation (on-land, air, or sea). Motorized traffic is prohibited except on roads or places built for this purpose unless the SEPA stipulates otherwise. There are opportunities to develop non-motorized outdoor activities (ski trips and dog sledding) to enhance the wilderness experience without the mechanical noise, exhaust, and traces of motor vehicles.61 Aircraft cannot be used for sightseeing in Svalbard, except for scheduled flights with tourists as passengers.62 The same regulation prohibits the use of hovercraft and hydrocopters in ocean areas that are not ice-covered and within one nautical mile of land. Environmental regulations regarding pollution and wastewater discharge are applied to all ships, including cruise vessels.63 National parks regulations64 prohibit the discharge of sewage and greywater within 500 meters of land and set fuel standards. The same regulation states that the vessels sailing to “natural reserves may not have more than 200 passengers on board”.65 The ban on heavy fuel oil (HFO) in national reserves, previously pertaining to national parks and nature reserves waters, is now applicable to Svalbard’s territorial waters.66

There is comprehensive regulation of maritime activities.67 This legislation is primarily designed for larger ships, but exceptions can be made for vessels shorter than 42 meters and/or carrying up to twelve passengers. The shipping companies that own the vessels and lease or charter them to tourism operators are responsible for meeting operation and safety requirements, outfitting, safety equipment, operation procedures, certification, and documentation pertaining to the vessels.

4.3. Requirements for organized outdoor activities

Tourism companies are subject to specific regulations regarding the establishment and operation of camps, reporting, equipment and safety. Safety regulations pertaining to land-based activities that are organized by tourism companies in Svalbard are largely covered by the specifications in the regulations for camp and field activities.68

The SEPA69 sets out rules for establishing permanent camps, stating that anyone seeking to establish permanent camps for public use outside areas that lack an approved land use plan must obtain permission. Camps, such as tents and other structures, must minimally affect soils and vegetation, preferably being sited on grounds with no vegetation. Camps are prohibited within 100 meters of cabins and settlements unless the owners grant permission. No camping, firepits, or related activities are allowed within the security zone around protected cultural remains, except on frozen and snow-covered ground. No fires in general are permitted on terrain that is covered by vegetation or soils. Rocks, driftwood logs, etc. used to support camp structures must be relocated or cleaned up after camp use. All litter must be disposed of at certified waste disposal sites. The establishment of camps requires adequate polar bear protection, such as signaling devices or dogs, and care must be taken not to follow or disturb animals.70 A specific section on polar bear safety measures outside settlements states that campers have a duty to know how to protect themselves against polar bears and must take precautions against harming or killing a bear. Exemptions are made for visitors and permanent residents partaking in organized tours.

Reporting is another requirement for tourism companies; plans for summer and winter activities must be filed no later than eight weeks before planned trips/activities. Tourism operators must report sailing plans to the Governor’s office, including landing spots and times for transporting people outside Management Area 10.71 Camping for more than one week in one location must be reported to the Governor (where, when, who, how many, and what). The notification must include information about polar bear security arrangements, waste disposal, and sanitation. Travel, camping, and any type of field activity in Area A Nordaustlandet and Edgeøya (which are zoned as important for science) must be reported to the Governor four weeks before the commencement of planned activities. Research and educational institutions and individuals who do not reside on Svalbard must report their planned field camps and camping outside of Area 10. This includes sailing itineraries and plans to go ashore. Individuals residing on Svalbard must report outdoor activities that include travel to or in South Spitsbergen, Forlandet, and Northwest Spitsbergen national parks and Southeast and Northeast Svalbard nature reserves.

Safety and equipment requirements encompass the security of the customers, guide competence, and the equipment involved. Tour operators and individual travelers must have insurance covering SAR and the transport of sick or injured people. The Governor decides how much insurance a company must carry. Tourism companies and their guides are responsible for their customers’ safety, and companies are required to ensure that their guides are familiar with the measures in the tourism regulations, as well as the regulations in Svalbard environmental law regarding the protection of flora, fauna, cultural remains, and the environment overall. Tourism companies that offer field activities must ensure that their guides have adequate competence and knowledge of environmental regulations; safety, including protection against polar bears; glacier activities, avalanches, and sea ice; first aid; local conditions, including climatic conditions; the natural environment; cultural remains; and responsible and careful travel. These requirements apply to guides indirectly, as the field representatives of tour companies. Companies and guides are further required to ensure that the equipment involved in activities, including weapons, fulfills safety requirements and is high quality.

4.4. Regulation instruments: taxes, fees, sanctions

The SEPA,72 as a legal entity, also regulates taxes and fees pertaining to i) visitors and outdoor recreation (people using the wilderness); ii) use of port facilities; and iii) pollution (sewage, water use, garbage handling, and building maintenance). An environmental tax, earmarked for environmental improvement projects, is collected from all travelers to Svalbard. The fees for using port facilities are levied according to ship gross tonnage and are collected for using the port and moorings. Smaller passenger vessels used for business and tender boats pay a fee per passenger. There are fees associated with the sewage systems, garbage collection, water use, management, and maintenance of buildings that apply to operators with building facilities for visitors. These fees are meant to incentivize reduced waste and increased recycling. The International Ship and Port Facility Security Code on Maritime Security (ISPS) (an amendment to the International Convention for Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS) Convention, 1974/1988) includes minimum security arrangements for ships, ports, and government agencies and also requires fees. For cruise ships and other international passenger vessels at the “Bykaia,” the Longyearbyen wharf, the ISPS fee is the lowest available. Tourism companies located in, and with headquarters or main offices in Svalbard, pay their taxes to Svalbard. The facilities or activities that a tourism company based in Svalbard conducts elsewhere are not subject to Svalbard taxation.73

The Governor of Svalbard has the main responsibility for monitoring and enforcing activities related to tourism in Svalbard. This ranges from the overall collective management of the natural environment and cultural remains according to the SEPA, to the management of all protected areas, char fishing,74 campsites,75 motorized traffic in off-road areas,76 and tourism and field activities.77 A party or person who damages nature by not following the regulations must pay compensation without consideration of the economic costs that result from the damage. The Governor decides the fine, which can be tested in court. Monetary compensation applies in cases where i) when an industry experiences economic loss because public right of access is restricted or inhibited due to damage to nature; ii) costs or losses associated with measures designed to hinder or mitigate damage to nature or rectify disturbance; and iii) costs incurred from cleaning up garbage.

4.5. Regional and international governance: shipping safety and environmental protection

Tourism at sea is governed by several regulations issued by the IMO and implemented by signatory countries. The regulations for shipping in polar waters found in the Polar Code are especially relevant. These regulations pertain to ship design, construction, equipment, operation, training, SAR, and environmental protection.78 The Polar Code is intended to supplement the SOLAS79 and MARPOL80 conventions to prevent hazards related to traveling in polar regions, such as ice, icing, severe weather, darkness, a lack of adequate navigational support, and remoteness that limits SAR capacities. Implementation of the Polar Code is an important step toward increasing personal and environmental protection. However, SAR exercises that tested Polar Code requirements for survival revealed several problems with SOLAS-certified rescue equipment.81

MARPOL, originally adopted in 1973 in response to several tanker accidents, has since been supplemented by several further regulations. In addition to preventing pollution from accidents, it includes specific requirements to prevent operational discharges, such as SOx (sulfur oxides), NOx (nitrogen oxides), and particles, into the air or sewage and garbage into the water, as well as a ban on disposing of plastics. In 2021, the IMO adopted a ban on the use and carriage of HFO in Arctic waters, but a series of exemptions will prevent the ban from coming into full effect until mid-2029.82 HFO is not only of concern regarding accidents, but also because burning it leads to significant emissions of air pollutants, including black carbon. The IMO’s Marine Environmental Protection Committee has also adopted a resolution on the voluntary use of cleaner fuels in the Arctic to reduce black carbon emissions.83 SOLAS includes several provisions that are meant to improve safety, such as rules on fire protection, lifesaving equipment and arrangement, radio communication, and navigation. In addition, control provisions allow port states (Norway, in the case of Svalbard) to inspect the ships of other flag states if there is reason to believe that they are not complying with the requirements. Specific requirements are also imposed on port facilities, which, in addition to controlling ships, include having adequate security plans.

SOLAS requires all state parties to establish, operate, and maintain rescue facilities, but SAR responsibilities are mainly regulated by the International Convention on Maritime Search and Rescue.84 This Convention requires states to ensure adequate SAR services in their coastal waters and encourage regional SAR agreements to pool resources and establish common procedures, training, and liaison visits. Based on initiatives within the Arctic Council, the Agreement on Cooperation on Aeronautical and Maritime Search and Rescue in the Arctic was signed in 2011 by the Arctic States.85 It refers not only to the SAR Convention but also to the 1944 Convention on International Civil Aviation (the Chicago Convention). In Norway, responsibility for SAR services is performed collectively by various governmental agencies, volunteer organizations, and private enterprises.86 For tourism operators, SAR can be both an obligation and a service.

5. Discussion

Our review of the national and international regulations that affect Svalbard tourism reveals potential conflicts and inconsistencies that have implications for the goal of ensuring that the tourism industry in Svalbard is environmentally, socially, and economically sustainable. We argue that many of these conflicts and inconsistencies are subtle and embedded in a detailed regulatory framework that precipitates from many policy levels. Our findings highlight how the well-established Svalbard regulations on nature conservation, area access and passage, and tour operator requirements and regulations may narrow the “action space” for the tourism industry.

One key aspect is vertical policy integration, where the Norwegian government’s interpretation of international-level policies and its goals for the Svalbard Archipelago support extensive tourism while also stipulating strict protection of the environment that attracts tourists. Horizontal policy integration is difficult because tourism activities fall into several sectors, i.e., commercial development, transport, environment, social and community issues, and safety. We argue that the lack of a central national “tourism authority” for Svalbard as well as the fragmentation of responsibilities obstruct a more unified tourism policy. This is exacerbated by the fact that the Svalbard policy scape belongs to different Ministries.87 Within the regulations we have scrutinized, the main conflict is found between wilderness preservation and commercial activities, such as tourism. Both are clearly expressed policy goals and both address sustainability, albeit from different perspectives (environmental versus socio-economic) and through different regulations. Unlike mainland Norway, conservation interests in Svalbard are prioritized over commercial interests and activities. This means that wilderness protection will almost always trump socio-economic aspects of tourism.

Another conflict is associated with the current policies that address both economic growth and nature preservation without guidance for how the resulting regulations should define acceptable limits for environmental and societal change or business development goals. To make a regulatory framework for wilderness preservation, measurable indicators of environmental attributes are needed. The challenges that potential regulatory conflicts cause mainly derive from the official Norwegian Svalbard policy propositions (as expressed in government white papers). These propositions neither clearly differentiate between overall goals nor address conflicting goals. Environmental protection to assure the continued sustainability of the wilderness may, therefore, conflict with tourism activities and reduce the potential for further tourism development. This illustrates an inherent difficulty in defining sustainability. Sustainability of what and for whom? Cruise ships exemplify this conflict. Limiting or banning large cruise ships from visiting Svalbard may increase environmental impacts from smaller-scale marine-based tourism, which occurs over a more extensive geographic area. Limiting high-concentration, large-scale cruise tourism may also limit economic revenue compared to other forms of tourism, counteracting the policy goal of sustainable tourism as an economic pillar of Svalbard.

We surmise that diversifying commerce and tourism operations may challenge the “Norwegianness” of Svalbard, the maintenance of which is one of the main objectives of the Svalbard policy.88 This is because the tourism industry attracts many international workers.89 The strict environmental protection regulations may lead to the differential treatment of tourism operations among treaty members, even if the same regulations apply to all. Given the international nature of tourism in Svalbard, foreign tourism operators may struggle to understand the existing laws and regulations, which are largely published in Norwegian, with only a few translated into English. Conversely, the goal of maintaining Norwegian communities and a Norwegian presence in Svalbard may be circumscribed by the lack of specific political and economic incentives to favor Norwegian business enterprises and innovation, as well as limited social incentives to make Svalbard particularly attractive to Norwegians.

In addition to these overarching challenges, we have identified several regulatory inconsistencies that complicate assessments of the balance between tourism development, community adaptation, and environmental status. A common denominator is that regulations are grounded in the precautionary principle and not necessarily integrated with knowledge that can define the carrying capacities of different areas in Svalbard.90 The strong emphasis on nature conservation becomes a fluid goal if the carrying capacities of key wildlife species, cultural heritage, and landscape categories are not defined or assessed within an operational management framework. Moreover, carrying capacity is subject to change due to climatic and environmental changes and the usage of new technology. Whether nature conservation goals are achieved becomes a negotiation between a large group of stakeholders regarding appropriate use, values, and norms. The lack of integration of scientific and other types of knowledge about the carrying capacity and resilience of species and habitats fosters insecurity and disagreements over the legitimacy of the foundations of regulations and management strategies.

As a result, a potential inconsistency emerges concerning how environmentally sound technology for tourism and the impacts of tourism activities are defined and assessed. The first inconsistency pertains to knowledge-based management. The SEPA’s use of the precautionary principle calls into question whether the regulations are fully informed by or based on existing expert and scientific knowledge.91 In addition, in-depth scientific knowledge about, for example, the birds in an area may not include data on how human activities affect them. This hampers the ability of operators to determine the environmental impact of tourism access and passage through an area. The lack of knowledge-based management may affect tourism operators’ evaluations of what kinds of activities are acceptable, allowed, or realistic for tourism activities.

The second potential inconsistency pertains to the differential regulatory treatment of the local population and visitors (including tourists). This is particularly evident in terms of area access and modes of travel (motorized vs. non-motorized) and may be difficult to justify in the long term as the composition of the Svalbard population changes. Currently, being designated “local” is solely based on a period of residency (often brief) which says nothing about the person’s skills, capability, or relevant experience in the outdoors. Simultaneously, the distinction between locals and visitors provides an opportunity for tourism operators to develop tourism products that solely target the local population.

The third inconsistency is grounded in environmental monitoring programs that would benefit from being linked more strongly to specific tourism activities. This could increase knowledge about changes in the environment and the impact of tourism activities. It is unclear whether existing regulations are suited to respond to changes in climate, which increase the length of the tourism season and, thereby, facilitate ambitions of year-round tourism. Moreover, the proposed access restrictions to some areas will lead to a greater footprint in areas that are currently available for tourism purposes.

The final inconsistency pertains to the regulations for organized outdoor activities. This includes the eight-week reporting period before activities can commence, which is likely to limit the planning and flexibility of tourism activities, especially given the rapidly changing sea ice and weather conditions. In addition, as of 2022, there is no formal system for certifying tour guides or specific skill requirements for them. These requirements are enforced indirectly through requirements for tourism operators, and several tour companies extensively train their guides. However, a system for guide certification is forthcoming, which will likely improve guide quality and contribute to displacing unprofessional actors from the market.

6. Concluding remarks and recommendations

Tourism is often heralded as an opportunity for economic development in the Arctic. The conflicts we have identified naturally have implications for Svalbard tourism operators, but these challenges are, nevertheless, likely to be similar in many other Arctic locations. We have shown that tourism opportunities can be circumscribed by national policy goals and international agreements. Using Svalbard as a case study, we conclude that while the international rules frame safe navigation and the reduction of tourism’s environmental effects in the Arctic, Norwegian national policies surpass this foundation and significantly narrow the action space for the tourism industry. The national policy aims to develop Svalbard as one of the world’s best-managed wilderness areas. Conservation interests are prioritized over commercial interests and activities that can affect the environment, in cases of conflicting goals. The common-access traditions in Norwegian management culture are partly counteracted by strict nature conservation goals in certain parts of Svalbard, especially the differential regulations for locals and visitors in terms of insurance, area access, hunting rights, and modes of travel.

Importantly, the Norwegian government encourages tourism while highly restricting it. The number and diversity of policies, rules, and regulations that pertain to tourism activities is formidable, obscuring what applies to which activities, seasons, and areas. This is especially true of access regulations and modes of travel, both of which vary in different areas on Svalbard. Furthermore, we have identified potential conflicts and inconsistencies in the regulatory landscape. These can easily become obstacles to developing sustainable tourism practices in Svalbard. Hence, there may be a need for a guide that allows operators to easily identify and access the most relevant and required information for their operations.

Recent amendments to the SEPA and associated regulations, will, if approved, limit the geographical area and types of tourism products and activities available in the Archipelago. The public’s and tourism stakeholders’ feedback on these changes may indicate a stronger need for predictability and justify greater national control of the Archipelago and its international community. Therefore, examining the window of opportunity and action space for tourism stakeholders becomes increasingly relevant.

We suggest that further research address several issues, including the factors that shape the tourism industry’s action space. More knowledge is needed on how both tourists and locals perceive the increasingly strict environmental management regime on Svalbard. Social acceptance of and compliance with regulations require management measures to be acceptable and legitimate. How the multitude of pertinent regulatory measures is operationalized in practical management is another topic worth probing. How the inconsistencies we have identified will be handled in the future, both in policy and management, is particularly important. Furthermore, investigating how certification schemes are reflected in policy statements as well as tourism practices will be necessary.

Our findings and conclusions should be considered in light of the potential limitations of the study. We have focused specifically on regulations that address tourism activities. However, the policy landscape in Svalbard also includes a wide range of regulations directed at other sectors, some of which can influence the interpretation and enforcement of tourism policies. Moreover, we have not specifically analyzed how the influence of international conventions and concerns, as well as national-level Svalbard policies, delimit the action space and boundaries of Svalbard tourism.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Trine Krystad from Visit Svalbard and Frigg Jørgensen from Association of Arctic Expedition Cruise Operators (AECO) for sharing their valuable insights about the study topic. The project “Sustainable Tourism in Svalbard: A Balancing Act” has received funding from the Research Council of Norway, grant number: 302914. FACE-IT has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement number: 869154 (www.face-it-project.eu).

NOTES

- 1. Jóhannesson, G., Welling J., Müller D., Lundmark L., Nilsson R, de la Barre S., Granås B., et al. Arctic Tourism in Times of Change. Uncertain Futures – from Overtourism to Re-Starting Tourism (Copenhagen: Nordic Council of Ministers, 2022).

- 2. Ministry of Climate and Environment. White Paper 8 (1999–2000). The Government’s environmental policy and the state of the environment.

- 3. The Svalbard Treaty. A treaty between Norway, the United States of America, Denmark, France, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, Great Britain, Ireland, and the British Overseas Dominions, and Sweden concerning Spitsbergen that was signed in Paris on February 9th, 1920.

- 4. Ministry of Justice and Public Security. White Paper 32 (2015–2016). Svalbard. (2016).

- 5. Norwegian Polar Institute. “Areas with access restrictions on Svalbard.” Website Title, 2022, https://www.sysselmesteren.no/siteassets/kart/temakart/ferdselsrestriksjoner/ferdsel2022_en.pdf

- 6. Gawor, Ł., Dolnicki, P. “Arctic Tourism Development with Regard to Legal Regulations and Environmental Protection,” Studies of the Industrial Geography Commission of the Polish Geographical Society 32, no. 2 (2018): 289–298; Kaltenborn, B., Østreng W., Hovelsrud, G. “Change Will Be the Constant – Future Environmental Policy and Governance Challenges in Svalbard,” Polar Geography (2019); Kugiejko, M. “Increase of Tourist Traffic on Spitsbergen: An Environmental Challenge or Chance for Progress in the Region?” Polish Polar Research 42, no. 2 (2021): 139–159; Saville, S. “Valuing Time: Tourism Transitions in Svalbard,” Polar Record 58 (2022): 1–13.

- 7. Hovelsrud, G., Kaltenborn, B., Olsen, J. “Svalbard in Transition: Adaptation to Cross-scale Changes in Longyearbyen,” The Polar Journal 10, no. 2 (2020): 420–442; Hovelsrud, G., et al. “Sustainable Tourism in Svalbard: Balancing Economic Growth, Sustainability, and Environmental Governance,” Polar Record 57 (2021): 1–7.

- 8. Kaltenborn, B., Emmelin, L. “Tourism in the High North: Management Challenges and Recreation Opportunity Spectrum Planning in Svalbard, Norway,” Environmental Management 17, no. 1 (1993): 41–50.

- 9. Kugiejko. “Tourist Traffic on Spitsbergen,” 139–159; Bonusiak, G. “Development of Ecotourism in Svalbard as Part of Norway’s Arctic Policy,” Sustainability 13, no. 2 (2021): 962.

- 10. Hagen, D. et al. “Managing Visitor Sites in Svalbard: From a Precautionary Approach Towards Knowledge-Based Management,” Polar Research 31, no. 1 (2012).

- 11. Saville, “Valuing Time: Tourism Transitions in Svalbard,” 1–13.

- 12. Jaskólski, M., Pawłowski, Ł., Strzelecki, M. “High Arctic Coasts at Risk—The Case Study of Coastal Zone Development and Degradation Associated with Climate Changes and Multidirectional Human Impacts in Longyearbyen (Adventfjorden, Svalbard),” Land Degradation and Development, (2018): 1–11.

- 13. Hovelsrud, Kaltenborn, and Olsen, “Svalbard in Transition: Adaptation to Cross-scale Changes in Longyearbyen,” 420–442.

- 14. Hovelsrud et al. ”Sustainable Tourism in Svalbard,” 1–7.

- 15. Viken, A. et al. “Responsible Tourism Governance. A Case Study of Svalbard and Nunavut,” in Tourism Destination Development: Turns and Tactics ed. A. Viken and B. Granås (Farnham: Ashgate, 2014): 245–262.

- 16. A. Grydehøj and M. Ackrén. “The Globalization of the Arctic: Negotiating Sovereignty and Building Communities in Svalbard, Norway,” Island Studies Journal 7, no. 1 (2012): 99–118.

- 17. Olsen, J., Vlakhov A., and Wigger K. “Barentsburg and Longyearbyen in Times of Socioeconomic Transition: Residents’ Perceptions of Community Viability,” Polar Record 58 (2022): e7.

- 18. Hovelsrud et al. “Sustainable Tourism in Svalbard,” e47.

- 19. Kaltenborn, B.P. and R. Hindrum. “Opportunities and Problems Associated with the Development of Arctic Tourism – A Case Study from Svalbard,” DN-notat (1996): 1; “Statistics,” Port of Longyearbyen, 2019, portlongyear.no.; “Overnattinger i Longyearbyen,” MOSJ, 2022, https://mosj.no/indikator/pavirkning/ferdsel/overnattinger-i-longyearbyen/.

- 20. Stokke, O.S. “Introductory Essay: Polar Regions and Multi-level Governance,” The Polar Journal 11, no. 2 (2022): 249–268.

- 21. Amundsen, H., Berglund, F. & Westskog, H. “Overcoming Barriers to Climate Change Adaptation – A Question of Multilevel Governance?” Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy 28 (2010): 276–289.

- 22. Tortola, P.D. “Clarifying Multilevel Governance,” European Journal of Political Research 56 (2017): 234–250.

- 23. Thomann, E., Trein, P. & Meggetti, M. “What’s the Problem? Multilevel Governance and Problem-Solving,” European Policy Analysis 5, no. 1 (2019): 37–57.

- 24. Zellen, B.S. “Tribe-State Collaboration and the Future of Arctic Cooperation: Moderating Inter-State Competition through Collaborative Multilevel Governance, from Yesterday’s Trading Posts to Today’s Arctic Council, ‘Arctic Exceptionalism’ is Here to Stay,” The Polar Journal 10, no. 1 (2020): 113–129; Young, O. R. “Arctic Governance – Pathways to the Future,” Arctic Review 1, no. 2 (2010): 164–185.

- 25. Ministry of Justice and the Police. White Paper 39, p. 34. Regarding Svalbard. (1974–75)

- 26. Ministry of Justice. White Paper 40. Svalbard. (1985–86).

- 27. Ministry of Trade and Industry. White Paper 50. Economic Measures for Svalbard. (1990).

- 28. Ibid.

- 29. Ministry of Climate and Environment. White Paper 22. Environmental protection in Svalbard (1994–95).

- 30. Ministry of Justice and the Police. White Paper 9. Svalbard. (1999–2000).

- 31. Ministry of Climate and Environment. Svalbard Environmental Protection Act, (2001).

- 32. Ministry of Justice and the Police. White Paper 22. Svalbard. (2008–2009).

- 33. Ibid.

- 34. Ministry of Justice and Public Security. White Paper 32 (2015–2016) Svalbard. (2016).

- 35. Norwegian Environment Agency. Amendments to the Svalbard Environmental Protection Act and Associated Regulations on Nature Conservation Areas, Motor Traffic, Camping Activities and Area Protection and Access to Virgohamna, 2021.

- 36. Sokolickova, Z., Meyer A., and Vlakhov A. “Changing Svalbard: Tracing Interrelated Socio-Economic and Environmental Change in Remote Arctic Settlements,” Polar Record 58 (2022): e23

- 37. Haugli, B. Elefanten i rommet. Svalbardposten. November 29, 2022. Elefanten i rommet (svalbardposten.no)

- 38. Bonusiak, “Development of Ecotourism in Svalbard as Part of Norway’s Arctic Policy,” 962.

- 39. Dawson, J., Johnston, M., Stewart, E. “The Unintended Consequences of Regulatory Complexity: The Case of Cruise Tourism in Arctic Canada,” Marine Policy 76 (2017): 71–78; Dawson, Johnston, and Stewart, “Unintended Consequences,” 71–78.

- 40. Johnston, M., Dawson, J., Maher, P. “Strategic Development Challenges in Marine Tourism in Nunavut,” Resources 6, no. 3 (2017): 25.

- 41. Johnston, Dawson, and Maher, 25.

- 42. Olsen, J. et al. “Cruise Tourism Development in the Arkhangelsk Region, Russian Arctic: Stakeholder Perspectives,” in Arctic Marine Sustainability: Arctic Maritime Businesses and the Resilience of the Marine Environment, eds. Pongrácz E., Pavlov V. and Hänninen N (Manhattan: Springer International Publishing, 2020), 365–389.

- 43. United Nations Environment Programme and World Tourism Organization. Making Tourism More Sustainable. A Guide for Policy Makers, 2005, http://www.unep.fr/shared/publications/pdf/DTIx0592xPA-TourismPolicyEN.pdf.

- 44. Hall, C. K. “Constructing sustainable tourism development: The 2030 agenda and the managerial ecology of sustainable tourism,” Journal of Sustainable Tourism 27, no. 7 (2019): 1044–1060.

- 45. Bowen, G. “Document Analysis as a Qualitative Research Method,” Qualitative Research Journal 9 (2009): 27–40.

- 46. Bowen, 28.

- 47. Hovelsrud et al. “Sustainable Tourism in Svalbard,” 1–7.

- 48. Bazeley, P., and K. Jackson. Qualitative Data Analysis with NVivo (2nd Seaman J. ed.) (London: SAGE Publications, 2013).

- 49. Ministry of Climate and Environment, Svalbard Environmental Protection Act, 2001.

- 50. Ministry of Climate and Environment, Ch. III–IV.

- 51. Ministry of Climate and Environment, Ch. II (5).

- 52. Ministry of Climate and Environment, Ch. III (11).

- 53. Ministry of Climate and Environment, Ch. V (39).

- 54. Ministry of Climate and Environment, Ch. IV (23–24).

- 55. Ministry of the Environment, Regulations Relating to Motor Traffic in Svalbard, 2002.

- 56. Ministry of Climate and Environment. Regulations Relating to Large Nature Conservation Areas and Bird Reserves in Svalbard as Established in 1973, 1973.

- 57. Ministry of Climate and Environment, Large Nature Conservation Areas, section 4.

- 58. Ministry of the Environment, Motor Traffic, 2002.

- 59. Ministry of Climate and Environment, Regulations on Fishing for Char in Svalbard, 2021; Ministry of Climate and Environment, SEPA, 2001.

- 60. Ministry of the Environment, Motor Traffic, 2002, Maps A and B.

- 61. Ministry of the Environment, Motor Traffic, comment on §1.

- 62. Ministry of the Environment, Motor Traffic, Ch. IV.

- 63. Ministry of Climate and Environment, SEPA, 2001.

- 64. Ministry of Climate and Environment, Major Bird Sanctuaries, 1973.

- 65. Ministry of Climate and Environment, Major Bird Sanctuaries, 1973, Section 16.

- 66. Ministry of Climate and Environment, SEPA, 2001, § 82 a.

- 67. Ministry of Trade, Industry and Fisheries, Ship Safety and Security Act, 2007.

- 68. Ministry of Climate and Environment. Regulations Relating to Camping Activities in Svalbard, 2002; Ministry of Justice and Public Security, Regulations Relating to Tourism, Field Operations and Other Travel in Svalbard, 1991.

- 69. Ministry of Climate and Environment, SEPA, 2001.

- 70. Ministry of Climate and Environment, Camping, 2002.

- 71. Ministry of Justice and Public Security, Tourism, Field Operations and Other Travel, 1991.

- 72. Ministry of Climate and Environment, SEPA, 2001.

- 73. Ministry of Finance, Law on Tax to Svalbard, 1998.

- 74. Ministry of Climate and Environment, Fishing for Char, 2021.

- 75. Ministry of Climate and Environment, Camping, 2002.

- 76. Ministry of the Environment, Motor Traffic, 2002.

- 77. Ministry of Justice and Public Security, Tourism, Field Operations and Other Travel, 1991.

- 78. “International Code for Ships Operating in Polar Waters,” IMO, accessed June 28, 2022, https://www.imo.org/en/OurWork/Safety/Pages/polar-code.aspx.

- 79. “International Convention for the Safety at Sea (SOLAS),” IMO, accessed 28 June 2022, https://www.imo.org/en/About/Conventions/Pages/International-Convention-for-the-Safety-of-Life-at-Sea-(SOLAS),-1974.aspx.

- 80. IMO. “International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships (MARPOL),” IMO, accessed June 28, 2022, https://www.imo.org/en/About/Conventions/Pages/International-Convention-for-the-Prevention-of-Pollution-from-Ships-(MARPOL).aspx.

- 81. Engtrø, E., Gudmestad O. T., and Njå O. “Implementation of the Polar Code: Functional Requirements Regulating Ship Operations in Polar Waters,” Arctic Review 11, no. 0 (2020): 47–69.

- 82. “IMO adopts an Arctic heavy fuel ban,” Arctic Today, June 17, 2021, https://www.arctictoday.com/imo-adopts-an-arctic-heavy-fuel-oil-ban/.

- 83. IMO. Resolution MPEC.342 (77), adopted 26 November 2021.

- 84. International Maritime Organization, Convention on Maritime Search and Rescue, June 28, 2022, https://www.imo.org/en/About/Conventions/Pages/International-Convention-on-Maritime-Search-and-Rescue-(SAR).aspx

- 85. Arctic Council. Agreement on Cooperation on Aeronautical and Maritime Search and Rescue in the Arctic. Accessed 28 June 2022, https://oaarchive.arctic-council.org/handle/11374/531

- 86. Christodoulou A., et al. “An Overview of the Legal Search and Rescue Framework and Related Infrastructure along the Arctic NorthEast Passage,” Marine Policy 138 (2022): 104985

- 87. Ministry of Justice and the Police. White Paper 22. Svalbard. (2008–2009).

- 88. Pedersen. T. “The Politics of Presence: The Longyearbyen Dilemma,” Arctic Review on Law and Politics 8 (2017): 95–108.

- 89. Saville, “Valuing Time: Tourism Transitions in Svalbard,” 1–13.

- 90. Viken et al., “Responsible Tourism Governance. A Case Study of Svalbard and Nunavut,” 245–262.

- 91. Sisneros-Kidd, A.M. et al. “Nature-Based Tourism, Resource Dependence, and Resilience of Arctic Communities: Framing Complex Issues in a Changing Environment,” Journal of Sustainable Tourism 27, no. 8 (2019): 1259–1276; Hagen et al. “Managing Visitor Sites in Svalbard,” 18432.