1 Introduction

The purpose of this article is to investigate why active state measures have dominated regional policies in Norway after 1945, compared with Sweden.

Regional policies consist of a broad range of measures and instruments regarding taxation, credit and loans, regional development funds, state companies and planning tools that are assigned to defined geographic areas.

This article focuses on factors of potential influence on regional policies. I argue that geographical and geopolitical factors in northern Norway can offer a better understanding than other factors of why active state measures have dominated the regional policies of governments of all colours in Norway. Furthermore, I argue that the absence of similar geographical and geopolitical factors in Sweden offers an understanding of why the state policies implemented by Swedish governments have not produced similar benefits in northern Sweden as the state policies implemented by Norwegian governments in northern Norway. The research question is: Which factors of influence have been the dominant factors behind the regional policies?

2 Theoretical factors of potential influence on the making of regional policies

The point of departure of this article is the theories and ideas that have influenced governments’ regional policy-making in Norway and Sweden after WW2. This point of departure corresponds to what economist Agnar Sandmo1 points out when he states that the history of economic theory is a history of ideas that have had a great influence on economic and social development – although often indirectly. During my analysis of the material, I realised that geography and the geopolitical position of northern Norway were dominant factors of influence on governments’ regional policy-making for northern Norway. Before I elaborate on the influence of geographical and geopolitical factors, I shall present some well-known thoughts from social science about the influence of ideas and theories, and some international forces affecting policy-making.

Regional policies in Norway have been based on a common political agreement amongst the political parties represented in the Norwegian Parliament (i.e. the Storting) after WW2. I shall show that this political agreement, in general, has been associated with the idea of an ‘active state.’ The concept of ‘active state’ may seem vague, however, a commonly accepted interpretation is that an active state is one in which the government intervenes in the economy and supplies welfare benefits.2 Renowned scholars have claimed that the active state concept consists of a set of social democratic ideas that have influenced policy-making.

According to the Norwegian historian Francis Sejersted,3 social democratic ideas were hegemonic between the 1930s and the 1970s in Norway and Sweden. I argue that these ideas continued to influence regional policy-making in Norway even after the 1970s – up until today. These social democratic ideas imply that ‘the competence and the role of the state were widened’4 and that government took an active state position. Policies of the active state are linked to ideas developed by the economist John Meynard Keynes in the 1930s.5 Keynes’ ideas, generally labelled Keynesian economics, provided a theoretical rationale for government to take an active position in the making of a broad set of measures in economic policies. I understand Keynesian economics as a recommendation for governments to intervene in their economies. In our Norwegian and Swedish cases, I include the implementation of generous welfare benefits as earmarks for the active state position of governments – in addition to social democratic ideas.6

Neo-liberalism ascribes the state a different role. Neo-liberalism is characterised by the idea of a strong but limited state whose main purpose should be to create a framework for the logic and mechanism of the market.7 Neither redistribution from rich to poor citizens or regions, nor control of the economy are legitimate goals for the state. Bourgeois intellectuals brought ideas from neo-liberalist economist Friedrich A. von Hayek8 to the Norwegian political debate. In his book ‘The Road to Serfdom,’ which was published in 1945, Hayek warned that continuing the state-planned economy from wartime risked would become a road to serfdom.9 Instead, he believed that the role of the state should be to create and protect competition in the market.10 During the two decades after the end of WW2, bourgeois political parties in Norway, with the Conservative Party at the forefront, objected to the active role of the state, embodied by the Labour government.

Another theoretical factor of potential influence in policy-making is Max Weber´s (1864–1920) theory of bureaucracy. We find a key component of Weber’s theory in his assertion that ‘[u]nder normal conditions, the power position of a fully developed bureaucracy is always over-towering.’11 Many social scientists today have argued, in line with Weber, that bureaucrats in public administration are not neutral instruments in the hands of shifting governments, but important agents.12

Weber’s theory finds support in studies of the Norwegian bureaucracy. Norwegian sociologist Rune Slagstad has claimed that politicising bureaucrats has been a feature of the Norwegian political system since 1814.13 Various Norwegian researchers have argued that influence from bureaucrats, who followed the Keynesian school of economics, may account for the active state policies of governments of all colours. One example of this influence is economist Erik Brofoss who held positions in the Labour governments in the two decades after 1945 as minister of trade, minister of finance and head of the Bank of Norway, as well as various other positions involved in the development of regional policies. Regional policies were in many ways his brainchild.14

Characteristic of the alleged influence of bureaucrats in central public administration positions, is the label ‘iron triangle,’ which has been used to describe the strong connections between high-ranking government bureaucrats, parliamentary committees and organised interests.15 The Norwegian political scientist Øyvind Østerud concludes that the label ‘iron triangle’ generally gave the impression of an interconnected association, but that nevertheless, bureaucrats and the bureaucracy still had an independent influence on public policy-making.16

At the end of the 1970s, Norwegian economists began to recommend that the government should play a minor role in a broad spectrum of policy areas. Norwegian governments, initially social democratic governments, approved of this recommendation to a certain extent and initiated a gradual turn towards market solutions in public policies in line with the neo-liberal turn in other countries at that time.17

Regarding regional policies in Norway, however, I maintain that the label ‘active state’ is a suitable characterisation of all Labour-led and bourgeois-led governments’ regional policies after WW2.

Geography, anthropology and similar academic disciplines have a long tradition of looking at how geography and geopolitical factors – meaning the impact of geographical factors upon public policies – interact with societal and individual factors. Other social sciences, most notably political science and sociology have tended to look at various societal and individual factors of influence on public policies, sometimes including geography and geopolitical factors as well. My perspective involves a comparison of the potential influence of geography and the geopolitical position of northern Norway versus individual factors. In this context, individual factors of influence are ideology, theories and ideas18 that work through ‘great’ personalities or strategists;19 the educational background of bureaucrats, and their formal position and motivations.

Geography has played, and still plays, a role in the centre-periphery political cleavage in Norway. In this context, the periphery refers to northern Norway. For example, political scientists Marta Rekdal Eidheim and Anne Lise Fimreite wrote an article titled ‘Geographical conflict in the political landscape,’20 where they argue that geography still influences Norwegian voting behaviour,21 and thus indirectly influences policy-making. I agree with Eidheim and Fimreite, and suggest further that municipal and county council representatives, as well as representatives from commercial interests in northern Norway, also influence policy-making by directly lobbying government ministers.

Northern Norway’s geography is rich in resources. It covers a good percentage of the Barents Sea with some of the world’s richest fishing grounds, oil and gas resources, and the potential presence of precious metals under the seabed. Global warming has the potential to open the Northeast Passage shipping route through the Barents Sea for lucrative merchant shipping. Moving goods along this route eliminates thousands of miles, saving time and money.22 Apart from the detrimental results of global warming on the earth, this represents an incentive for the Norwegian government to pass policies to strengthen harbours and shipyards in northern Norway.

Norway shares many of these geographical resources with Russia, and earlier the Soviet Union, which have been considered adversaries of Norway. Therefore, I establish northern Norway’s geopolitical position itself as a factor of influence on Norway’s regional policies.

This article could have included the influence on public policies from the European Union, and the European Economic Agreement (EEA). Norway signed the EEA treaty with the European Union in 1994. It regulates and limits the Norwegian government’s regional policies in specific areas. Consequently, it is a factor of influence on regional policies in Norway. The EEA has not been included because I regard it as a constant in the sense that it has the same influence on the regional policies of all governments.

Globalisation could also have been included as a factor of influence on the depopulation of small settlements and deindustrialisation in northern Norway and northern Sweden. However, I also regard this factor as a constant. Globalisation represents strong forces influencing regional policies in both countries that cannot be challenged by small nations’ regional policies.

3 Method

I have analysed a selection of documents issued by social democratic and bourgeois governments on regional policies. Throughout the article, when I refer to ‘Norwegian governments,’ I use ‘social democratic government’ to denote a Labour party or Labour-party-led government and ‘bourgeois government’ to denote a government led by one of the centre-right political parties (i.e. Conservative Party, Christian Democratic Party or Centre Party).

The article focuses on regional policies in Norway (i.e. Nordland, Troms and Finnmark counties) and Sweden (i.e. Norrbotten and Västerbotten counties).

There are several reasons for comparing northern Norway and northern Sweden. As already mentioned, social democratic ideas were hegemonic in both countries until the 1970s,23 and economic forces boosted the urbanisation and depopulation of small communities in both countries during this period.24 They also have geographical similarities – most of northern Norway and a smaller part of northern Sweden belong to the Arctic area of the northern hemisphere, which is sparsely populated.25 Furthermore, they both belong to the geographical periphery of their countries.

Data were collected using a pragmatic qualitative method to identify various words connected to the ideas behind regional policies. The main data comprise online government documents. Some data were obtained also from other sources: online programmes from political parties obtained from the Norwegian Centre for Research Data (NSD), two online studies by an American scholar about regional policies in Norway, a printed biography of a prime minister, a printed biography of a political party leader, and a printed history book by a renowned historian. I am not aware of public documents that render major differences from the documents that are put forward here. All quotes from public documents are translated from Norwegian to English by the author, unless otherwise specified. The data comprising the results of regional policies are registry statistics.

The analysis consists of two comparisons. One compares indicators of active state measures in regional policies in Norway under social democratic and bourgeois governments. This comparison examines the ideas underlying regional policies by social democratic and bourgeois governments after 1945. The second comparison looks for similarities and differences between Norway and Sweden.

Sometimes there is a discrepancy between ideas and results. In the case of northern Norway and northern Sweden, peripheral settlements dominated by fisheries, forestry and agriculture have been deprived wholly or partially of schools, post offices and other establishments. Behind this deprivation, strong forces have been at work to uphold a continuous movement of people to central areas of the country.26 However, this article chiefly compares the content of regional policies, not the results of the government’s regional policies in Norway. Consequently, the discrepancy between ideas and results in Norway lies outside the main scope of the article. The comparison of Norway and Sweden represents an exception because it also focuses on results.

4 The active state in regional policies in Norway – a comparative analysis of social democratic and bourgeois policies

4.1 The era of Labour governments, 1945–1965

Post-WW2 reconstruction marked the start of the social democratic era in Norway. In contrast to most other Western governments, Norway’s social democratic government adopted more ambitious goals for its economic policies.

A joint programme formulated by leading figures in the Social Democratic Labour party and the bourgeois parties in 1945 came to exert heavy influence on all policy fields during the first decade that followed. This programme, titled the ‘Communal Programme’ (Fellesprogrammet), stated that the purpose of economic life was to create work for everyone and to increase production.27

In 1947, the government launched a ‘national budget’ as an instrument aimed at authorising the government to regulate the country’s economic activities.28

The main goal of Norway’s reconstruction was to establish worthy and equal living standards throughout the country as soon as possible. An active state was an inevitable implication of this aim, and was widely accepted, also by the bourgeois parties, primarily because of the need for reconstruction in areas of northern Norway devastated during WW2. A central parliamentarian in the Conservative Party at that time – and later prime minister for a short time – John Lyng, wrote in his memoirs about his party’s support:

Words and concepts like social coordinated regulation by the government – in contrast to private initiative, innovation and free enterprise – were in frequent use by all sides (…). But this support was defined by the situation at that time and did not last long.29

In 1950, the Labour government launched an economic programme for northern Norway. The programme challenged the traditional bourgeois ideas of the proper role of the state in economic affairs. The bourgeois parties expressed fear that if the state were to interfere with economic development, short-term political considerations would guide investments rather than the country’s best prospects. Advocates of the theories of John Maynard Keynes in the social democratic government and party supporters from an elite group of economists were central policymakers.30 Keynesian economics proved to fit well for the state-planned economy preferred by the government.

One of the government’s post-war priorities was the rebuilding of homes destroyed by the Nazi occupation forces in 1944 in the two northernmost counties. A broader programme was established in 1951,31 aimed at creating a development programme for all three counties in northern Norway. This programme contained special taxation rules and other extraordinary instruments for the region. Opposition parties argued that the ‘northern Norway programme’, as it was labelled, embodied a new control initiative by a central authority over what had traditionally been local affairs.32

The beginning of the Cold War created a vulnerable situation for northern Norway because its border with the Soviet Union became a border between two blocs in the new bipolar world system. According to Soderlind,33 the defence aspects of northern Norway’s reconstruction have generally been played down. However, the government’s reconstruction plan for northern Norway, published in 1951, stated that it was an important obligation not only for Norway to build up northern Norway, but also for the Western world, which cooperated through the Organisation for European Economic Cooperation (OEEC) and the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO).34 Norway joined NATO as soon as it was established in 1949, and northern Norway was quickly militarised, with the construction of new garrisons, airports, submarine bases and coastal batteries, which facilitated social and economic development in the neighbouring communities.35 Against this background, it can be concluded that military investments in northern Norway were part of the government’s regional policies for the area. This conclusion resonates with Olav Foss et al.’s claim that the aim of regional policies to ensure high population spread was probably an important aspect of territorial control in northern Norway.36

The Norwegian social democratic government soon acknowledged that northern Norway needed more than reconstruction. Therefore, in 1951, a new law was passed to enable entrepreneurs to invest funds to support new industries in northern Norway and other areas characterised by a lack of workplaces and low incomes.

The Norwegian government might have launched an alternative plan for northern Norway’s reconstruction by moving the labour force from north to south in response to the growing demand for workers in southern Norway, thereby reducing increasing unemployment in the north. However, the government opposed that alternative. Prime Minister Einar Gerhardsen declared in his memoirs that “[T]his was not a desirable solution.”37

The social democratic government’s planned economy encountered strong objections and criticism from the bourgeois political parties and employers’ organisations during the 1950s.

4.2 Coalition governments begin in 1965 – but no significant changes in regional policies

Disagreements within the social democratic Labour party in the early 1960s cleared the way for a shift to bourgeois-party governments. However, this did not change the course of action of previous Labour governments in terms of using public economic mechanisms and regional development policies.38,39

The 1965 programme of the Conservative Party exhibited an ambiguous attitude towards the active state in regional policies.40 On the one hand, the programme expressed scepticism when it declared that “[t]he government leading the establishment of industries as a mechanism in regional development has been very unfortunate. A lot of capital has been lost to insolvent and bankrupt enterprises.”41

The first long-lasting bourgeois government was established in 1965 after the end of the social democratic government’s rule from 1945 to 1965. A prime minister from the Centre Party, Per Borten, a party originally established by agrarian organisations, headed a coalition government with the three other bourgeois parties in Parliament. The Centre Party’s ideological basis was, and still is, a concern for living conditions outside the central regions of Norway.

According to Soderlind, the policies of regional growth that existed were used actively by the new bourgeois government, and “augmented with additional subsidies and controls over the location of large enterprises and institutions.”42 In 1968, the bourgeois government created a special state-owned company – ‘The Norwegian Industrial Estates Company’ (Selskapet for industrivekstanlegg) came to be its English name. It was empowered to construct and operate industrial sites in approved growth centres.43 Growth centres were an idea that originated from the Regional Development Fund (Distriktenes utbyggingsfond) in the early 1960s during the reign of the social democratic government. These examples show that at the time, the bourgeois government did not move away from the active state in its regional policies, but rather enhanced it.

To improve educational opportunities in northern Norway, a state-run university in Tromsø was established by the bourgeois government in 1968. In the 1970s, 80s and 90s a new type of higher education institution called ‘distriktshøgskole’ (regional university college) was established in three towns and two country towns in northern Norway. The name signals the role of these institutions in the regional policies of social democratic and bourgeois governments.

The governments retained their conviction in active state intervention as a vehicle to increase economic development throughout the country. This belief was expressed in the way in which the governments regulated and controlled capital and the credit markets as a continued aspect of their active regional policies.44

4.3 Era of neo-liberalism in general policies but not for regional policies, 1980–2022

The 1980s saw two bourgeois governments and one social democratic government. One can hardly discern significant differences between these governments’ regional policies during this period. In 2015, the bourgeois government published a retrospective document about regional policies in Norway over the previous 50 years. The document characterised the 1980s as if neo liberalism had started:

…[P]olicies changed in the 1980s. There were fewer large industrial projects, and with the liberalization of interest and credit policies, the state became less important as a source of capital. There was less faith in official planning, and new methods for governing society were introduced, including goal management and competitive tendering.45

However, regional policies in Norway remained influenced by the ideas of the active state, as the next two quotes indicate. The first quote comes from the Conservative Party’s programme for the parliamentary election in 1988. It stated: “The overall goal of the Conservative Party’s regional policy is to improve economic development and to safeguard settlement and living conditions in all parts of the country.”46

This quote, especially the words “all parts of the country,” signalled a reassertion of the active state in regional policies, which leading politicians all along the political continuum had included in the Communal Programme in 1945.

Likewise, the social democratic government of 1990–1996 echoed the political ideas from the early reconstruction period in a message to Parliament: “The main aim for integrated regional policies is to contribute to developing sustainable regions in all parts of the country, with balanced settlement patterns, and equity in employment and welfare services.”47

Note the phrase ‘in all parts of the country’ in the two last quotes. As we shall see, this phrase continued to be the most repetitive element in the regional policies of all governments.

The bourgeois coalition government in office from 1997 to 2000 (Bondevik I) declared that its “[…] central aim for the regional policies is: to maintain the main settlement pattern; [and] to develop robust regions in all parts of the country.”48 In a subsection of the same document, the government declared that regional policies in all areas were the most important factors affecting living conditions and settlement patterns, and that the government’s policies aimed to compensate for some of the competitive disadvantages of being far away from the markets.

In its inaugural session, the bourgeois government in office from 2001 to 2005 (Bondevik II) declared its understanding of regional policies in the following way: “Well-intentioned economic development policies are good regional policies as well. Important fishing industries, fish farming industry, agriculture, and tourist industry contribute to wealth creation in sparsely populated areas and good living conditions throughout the country.”49

The social democratic government in office from 2005 to 2013 (Stoltenberg II) declared: “[The government] intends to keep the main elements in the settlement pattern. We will use the human and natural resources throughout the country to make the greatest possible national wealth, secure living conditions, and give everybody genuine freedom to settle wherever they want.”50 This declaration received broad support in Parliament.

The last bourgeois government, headed by Solberg, was a coalition government that ruled from 2013 to 2021. To bring this section to a close, I present the basic content of the Solberg government’s regional policies in Norway:

- regionally differentiated social security contributions for employers

- lower income tax for individuals

- generous financing of studies for students who settled there after having finished their studies

- reduced electricity tariffs for households

- for the most northern districts (Nord-Troms and Finnmark), the government exempted employers from paying a social security contribution.

Table A1 in the Appendix summarises the body of evidence identified as ‘active state indicators’ in social democratic-led and bourgeois coalition governments’ regional policies since 1947.

The overall picture demonstrates that bourgeois political parties and bourgeois governments maintained an active state role in regional policies in Norway. This applies to each bourgeois government after the mid-1960s, when these parties formed their first government after WW2.

5 A comparative analysis of regional policies in Norway and Sweden

5.1 Swedish governments move people from north to the middle and south, 1945–1970

Similar to Norway, tension exists between the centre and periphery in Sweden as well.51, 52 But the centre-periphery political cleavage has been less prominent in Sweden than in Norway.

The main goal of the social democratic government in Sweden immediately after 1945 was to build a better future for its inhabitants. Full employment was another goal. These goals were like those of the Norwegian social democratic governments during the same period.

In Sweden, which formally remained neutral after WW2, the belief in a Soviet military threat made the county of Norrbotten in northern Sweden an important area in the Swedish defence effort, resulting in further strategic investments in military fortifications along the coast.53 These military investments required manpower, and that part of the country still had a surplus of manpower.

Sweden’s industry had not been ruined by the war. Its northern territories, like the rest of the country, experienced strong economic growth in the post-war period.54 Molinder et al.55 have highlighted an important aspect of Swedish policies during the early post-war period, namely that they were strongly aimed at moving labour from northern Sweden to the middle and south, most notably through relocation policies.

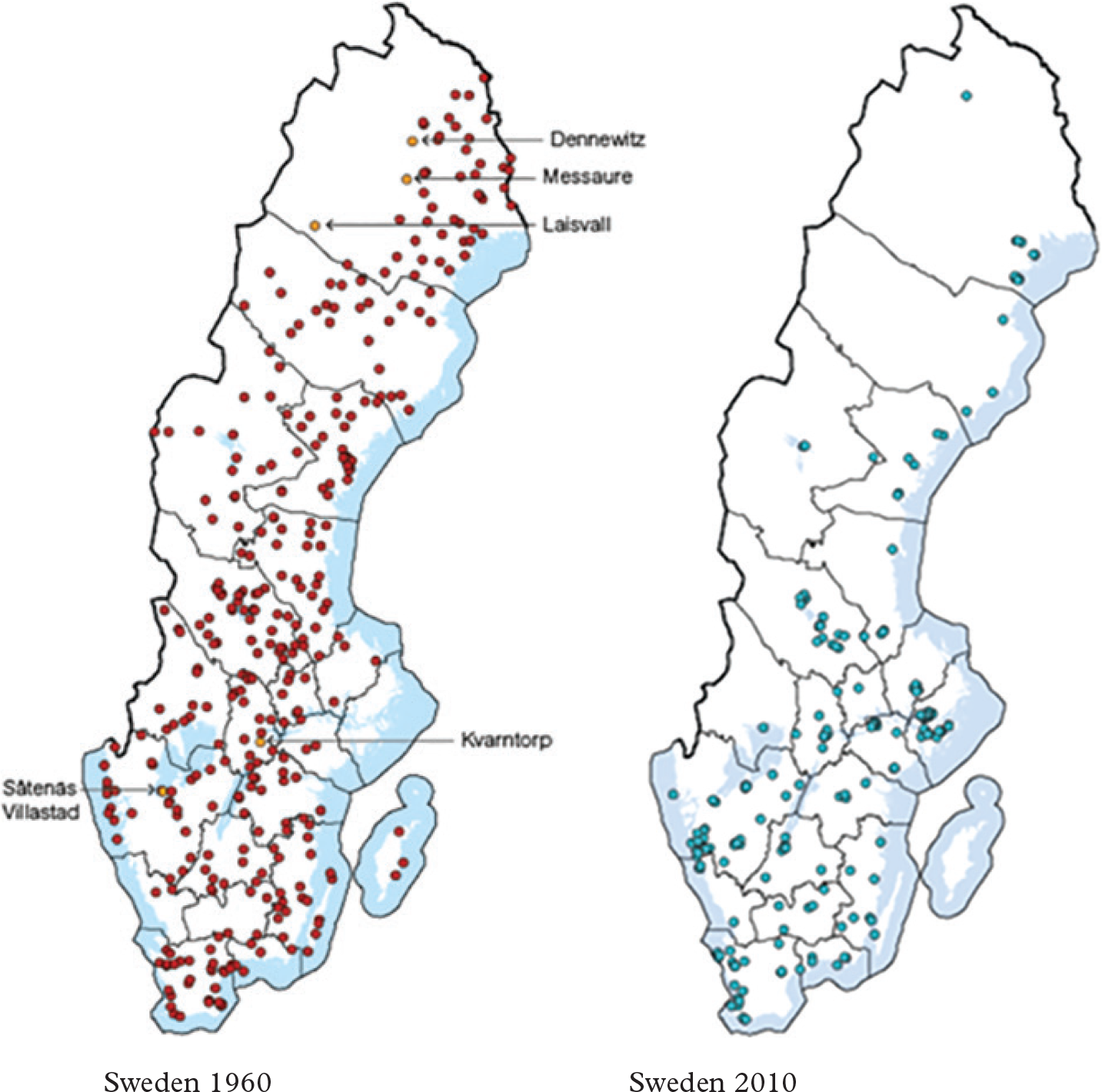

As a result of these relocation policies, a huge migration from the north to the south followed.56 Five hundred small settlements disappeared during the years 1950 to 2010. Map 1 below shows the many townships and villages that disappeared from northern Sweden between 1960 and 2010. Some settlements disappeared from the south, as the table shows, but mostly because they merged with neighbouring towns. The Norwegian historian Francis Sejersted paraphrased Swedish political scientist Bo Rothstein’s statement that this migration introduced modern state interventionism into Swedish public administration. According to Sejersted, the way in which the Swedish government became a directing agent of labour force migration evolved into a special aspect of Swedish social democracy.57

Map 1. Number of Swedish townships and villages, 1960 and 2010

Source: Statistics Sweden

5.2 Swedish governments start to stimulate employment in northern Sweden, 1970–2022

Regional policies changed around 1970. At that time, a major policy shift occurred, directed towards a policy of stimulating employment in northern Sweden through regional subsidies58 and other measures, like relocating jobs to certain northern towns and incentives to invest in energy, battery factories and mines. Typically, Swedish governments began arguing that domestic policies should be applied throughout the country (“hållbar utveckling i alla delar av landet”).59 Branches of government services were relocated to towns in northern Sweden, and ‘regional balance’ became a central concept. This change in regional policies has lasted until today.

A forerunner of this shift was already visible in 1965 when the Swedish government decided to establish a university in Umeå. The intention was not only to make higher education available to more people but also to promote development in this northernmost region.60 Taking a closer look at higher education as part of regional policies demonstrates that Norwegian governments started later than Swedish governments in this respect. From 1968 to 1994, Norwegian governments established one university and four university colleges in northern Norway (see table A2 in the Appendix). The establishment of higher education institutions has proven to have a large positive effect in northern Sweden and northern Norway.61 ‘Knowledge cities’ showed more positive development than other municipalities, as the Norwegian political scientist Jonas Stein has observed.62 Therefore, it can be argued that regional policies moved in a similar direction in Sweden and Norway after the 1970s with regard to knowledge cities.

5.3 Differences instead of similarities

I have, however, observed another trend in the population development that Stein describes, which challenges Stein’s picture of a similar population development between northern Norway and northern Sweden. Figure 163 shows that the smallest, small, and medium-large municipalities in northern Norway have lost fewer inhabitants than municipalities of a comparable size in northern Sweden. Furthermore, figure 264 shows that the number of inhabitants in the industrial town of Rana in northern Norway has a higher percentage of inhabitants measured as a percentage of the national population in 2015 than in 1955, while the industrial town of Skellefteå in northern Sweden has a lower percentage in 2015 than in 1955. Finally, as observed by Stein,65 a larger percentage of the national population lives in northern Norway than in northern Sweden. This suggests that Norwegian regional policies have achieved better results from a demographic perspective.

While Stein claims that Norway has not followed a different path than Sweden in its regional policies, my interpretation of Stein’s data suggests that Norway has followed a different path than Sweden. The reason for this lies in the fact that Norwegian governments have spent comparatively more in northern Norway than Swedish governments have spent in northern Sweden throughout the period after 1945. This spending has enabled northern Norway to retain a larger part of the national population compared to northern Sweden.

It may be concluded that the migration from the north of Sweden to the middle and south of the country during the post-WW2 period, and the policy incentives to invest in northern Sweden from around 1970, are telling examples of active state policies.

Comparing the two countries, we can see that northern Norway and northern Sweden display important similarities and differences. Table 1 summarises these similarities and differences.

| Similarities and differences | Norway | Sweden |

|---|---|---|

1. Active state in regional policies |

Yes, lots of government investments and other benefits to northern Norway | Yes, but compared to Norway, smaller government investments and other benefits to northern Sweden |

2. Hegemonic ideology |

Social democratic | Social democratic |

3. Labour market policies |

Full employment | Full employment |

4. Military presence |

Strong | Strong |

5. Geography |

Rich fishing, oil and gas industries, potential for precious metals under the seabed | Rich mining industry (mainly iron ore); potential for additional precious metals on land |

6. Geopolitical factors |

Important factors: land and sea border with Russia, proximity to the Northeast Passage shipping route | Absence of the geopolitical factors that are present in northern Norway |

7. Peculiarity: Centre-periphery political cleavage |

Strong | Weak |

Source: Own compilation

Deteriorating security after Russia’s occupation of Crimea in 2014 and the war in Ukraine in 2022 were factors that prompted Sweden to apply for NATO membership in 2022.58 The implications of NATO membership for northern Sweden are beyond the scope of this article.

6 Discussion

The main purpose of this article is to investigate factors influencing regional policies in Norway after WW2. A secondary purpose is to compare these policies with the Swedish government’s regional policies in Sweden. I begin the discussion by looking at the policies in Norway.

We have seen that active state measures are the dominant factors influencing regional policies in Norway after 1945. Northern Norway has benefitted from a strong centre-periphery political cleavage. Through the voting channel and lobbyism, governments have been partly forced and partly persuaded to give concessions to the periphery (i.e. northern Norway). Nevertheless, from what we have seen in sections 4 and 5, geographical and geopolitical factors stand out as the most dominant factors of influence on active state measures in regional policies in Norway.

Furthermore, we have seen that the influence of bureaucrats and the bureaucracy on policy-making has been a much-debated issue amongst Norwegian scholars. Many studies point to Max Weber’s theory of bureaucracy. In summary, there is a widespread consensus in Norwegian academic circles that the influence of bureaucrats was substantial on general policies in Norway in the first decades following WW2. However, I argue that the influence of geographical and geopolitical factors on regional policies in Norway has exceeded the influence of bureaucrats and the bureaucracy since WW2.

We have seen that even bourgeois political parties, after having opposed the active state policies of the Labour governments, continued similar policies when they came to power in the 1960s. This change from opposition to support for active state policies in Norway by bourgeois political parties in government could be attributed to many factors.

The situation in 1945 gives a clue to understanding why governments of all colours have considered the dominant influence of geographical and geopolitical factors on regional policies in Norway. The primary reason that bourgeois political parties supported the Communal Programme of 1945 was the urgent need to rebuild the areas of northern Norway that had been devastated during WW2. The Communal Programme implied active state measures. The urgent need to rebuild these areas made bourgeois political parties’ ideological fear of active state measures as “a road to serfdom” seem less evil. Additionally, a new security situation had arisen between the Eastern and Western powers immediately after WW2. The Soviet Union had become the new enemy of the Western powers, and Norway joined the Western military alliance NATO in 1949. Suddenly, the most northern part of Norway, Nord Troms and Finnmark, became NATO’s closest geographical area to the alleged enemy in Arctic Europe. Finnmark county even shared a land and sea border with the Soviet Union. This new geopolitical security situation left bourgeois political parties with no other option but to support the strengthening of military installations in northern Norway, and to continue to strengthen settlement patterns through extraordinary regional policies. The social democratic government in power at the time could, without ideological doubts, practice Keynesian economics because it was heavily influenced by social economists of a Keynesian type amongst the ministers and people close to the government. These economists were eager to introduce state-planned rebuilding and funding.

Later, from around the 1980s, new factors of influence on regional policies came into play in northern Norway, with the discovery of oil and gas resources and the potential for precious metals in the seabed, as well as the proximity to the Northeast Passage shipping route that will probably soon open to lucrative merchant shipping. All of this makes it essential to have active state measures in infrastructure and other public goods as an aspect of maintaining territorial control in northern Norway.

Far from advocating geographical and geopolitical determinism, it can be argued that the geographical and geopolitical factors in northern Norway are important in explaining the active state role taken by all governments since 1945. This encompasses the region’s climate, fisheries, oil and gas, Northeast Passage from Asia to Europe, as well as the geopolitical position represented by its land and sea borders with Russia.

Now, I turn to a comparison of regional policies in Norway and Sweden.

The data suggests that since 1945, the governments in Norway and Sweden have been influenced by social democratic ideas that prescribe active state measures. Yet active state policies differed in the two countries’ northernmost regions until the 1970s. How can we understand this difference?

Both the Swedish and Norwegian governments regarded the Soviet Union as a military threat from the beginning of the Cold War. Therefore, the Swedish government invested heavily in military infrastructure and equipment in northern Sweden, but the Swedish government had other challenges than the Norwegian government.

None of Sweden’s northern areas (nor anywhere else) were devastated during WW2. However, there was one urgent problem in Sweden in the first decades after WW2: the highly industrialised central and southern areas of the country needed a bigger labour force. At the same time, there was high unemployment in northern Sweden. The social democratic government at the time had few doubts about using active state measures to move people from northern Sweden to the central and southern areas of the country. This movement of the labour force helped to solve the country’s labour market problems.

Even though the Swedish government started to make more generous regional policies aimed at northern Sweden from around 1970, the resulting investments and benefits have been minor compared to those in Norway. How can we understand this?

One answer is that the centre-periphery political cleavage in Sweden is less in favour of the political periphery (i.e. northern Sweden) than in Norway (i.e. northern Norway). But more importantly, it can be argued that the generous regional policies in Norway are the result of a shared interest by Norway’s centre and periphery in keeping a strong hand on the region’s rich resources, strengthened by the alleged threat from the Soviet Union – and later, Russia.

The geopolitical situation may change after Sweden’s 2022 application for NATO membership, the consequences of which are beyond the scope of this article.

7 Conclusion

Ideas around the active state in regional policies in Norway have had a strong influence on the regional policies of governments of all colours after 1945. The active state role is linked to influences from two factors: northern Norway’s geographical resources and geopolitical situation vis á vis the Soviet Union – and later, Russia. These two factors gain political strength through the shared interest of Norway’s centre and periphery in keeping a strong hand on the region’s resources. These factors explain why even bourgeois governments have chosen active state measures in northern Norway. The influence of Keynesian economics and bureaucrats on the government’s regional policies matter less.

In comparison, northern Sweden lacks the geographical and geopolitical factors of northern Norway, which explains why Sweden has used fewer active state measures than Norway in its northern districts.

Regarding Norway, it can be argued that governments that might consider turning away from active state measures in regional policies in Norway will risk losing a substantial amount of support.

About the article

An earlier issue of this article was presented at the NORDOM XVI conference (Nordic meetings about the history of economic ideas) at Østfold University College 26–27 August 2022. I wish to express my thanks to the participants there for their valuable comments.

I am grateful to two reviewers from the Arctic Review on Law and Politics who have given valuable feedback to previous versions of the article.

NOTES

- 1. Agnar Sandmo, Samfunnsøkonomi – en idéhistorie (Oslo: Universitetsforlaget, 2007, second edition), 370.

- 2. William J. Barber. “Keynesianism,” in The Oxford Companion to Politics of the World, ed. Joel Krieger (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001, second edition), 465.

- 3. Francis Sejersted, Sosialdemokratiets tidsalder: Norge og Sverige i det 20. århundre, (Oslo: Pax, 2005), 15.

- 4. Ibid., 333.

- 5. John Maynard Keynes, The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money (London: BN Publishing, 2008).

- 6. Sandmo, Samfunnsøkonomi – en idéhistorie, 370.

- 7. Olav Innset, Markedsvendingen. Nyliberalismens historie i Norge (Oslo: Fagbokforlaget, 2020), 100–101.

- 8. Fredric A. von Hayek, The Road to Serfdom (University of Chicago Press, 2007).

- 9. Ibid.

- 10. Bent Sofus Tranøy, “Ola Innset: Markedsvendingen: Nyliberalismens historie i Norge,” (Bokmelding), Tidsskrift for samfunnsforskning, Vol. 62, Utg. 3, (2021): 310. https://doi.org/10.18261/issn.1504-291X-2021-03-07.

- 11. Max Weber, “Bureaucracy,” In Economy and Society: An Outline of Interpretive Sociology, eds. Guenther Roth and Claus Wittich (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1978), 991.

- 12. Morten Egeberg and Inger Marie Stigen, “Explaining Government Bureaucrats’ Behaviour: On the relative importance of organizational position, demographic background, and political attitudes,” Public Policy and Administration 36, no. 1 (2021): 3–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/0952076718814901.

- 13. Rune Slagstad, “De politiserende embetsmenn [the Politicizing Civil Servants],” In Rune Slagstad (ed): Rettens ironi. Studier i juss og politikk. [The Irony of Law. Studies in Law and Politics] (Oslo: Pax forlag, 2011).

- 14. Harald Baldersheim, “Håvard Teigen: Distriktspolitikkens historie i Norge,” Tidsskrift for samfunnsforskning, 62, no. 2, (2021): 208–211. https://www.idunn.no/doi/full/10.18261/issn.1504-291X-2021-02-06

- 15. Øivind Østerud, Statsvitenskap. Innføring i politisk analyse (Oslo: Universitetsforlaget, 2014, 5. edition), 74.

- 16. Ibid., 75.

- 17. Innset, Markedsvendingen. Nyliberalismens historie i Norge, 99.

- 18. Sandmo, Samfunnsøkonomi – en idéhistorie, 370.

- 19. Slagstad, De Nasjonale Strateger.

- 20. Marta Rekdal Eidheim and Anne Lise Fimreite, ”Geografisk konflikt i det politiske landskapet: En fortelling om to dimensjoner [Geographical conflict in the political landscape. A tale of two dimensions],” Norsk statsvitenskapelig tidsskrift, 36, no. 2 (2020): 56–58. https://doi.org/10.18261/issn.1504-2936-2020-02-0.

- 21. Ibid.

- 22. Björn Gunnarsson and Arild Moe, “Ten Years of International Shipping on the Northern Sea Route: Trends and Challenges.” Arctic Review on Law and Politics 12(2021): 4–30. https://arcticreview.no/index.php/arctic/article/view/2614/5113.

- 23. Sejersted, Sosialdemokratiets tidsalder: Norge og Sverige i det 20. århundre.

- 24. Nils Aarsæther, “Periferiens sentralitet,” Plan (2016): 95–104. https://doi.org/10.18261/ISSN1504-3045-2016-03-04-19.

- 25. Anders Lidstrøm, “Socialdemokraternas tillbakagång 1973–2014,” (Umeå universitet, 2018).

- 26. Hans Henrik Bull, Victor Norman and Kristian Aasbrenn., “Det handler om Norge,” Plan, 4. (2020): 8–15. https://doi.org/10.18261/ISSN1504-3045-2020-04-03.

- 27. The Prime minister. Arbeid for Alle. De politiske partienes felles program (Regjeringen, 1945).

- 28. St. meld. 10 1947 (Government document), “Om Nasjonalbudsjettet 1947.” https://www.stortinget.no/no/Saker-og-publikasjoner/Stortingsforhandlinger/Lesevisning/?p=1947amp;paid=2&wid=b&psid=DIVL427&pgid=b_0189.

- 29. Jon Lyng, Brytningsår. Erindringer 1923–1953 (Oslo: Cappelen, 1972).

- 30. Arild Sæther and Ib. E. Eriksen, “Ragnar Frisch and the postwar Norwegian economy,” Econ Journal Watch, (2014), 11(1): 59.

- 31. Håvard Teigen, “Distriktspolitikk gjennom 50 år – Strategane og avviklinga,” Nytt Norsk Tidsskrift 29, no. 2 (2012): 157–65.

- 32. Ibid.

- 33. Steven Soderlind, “Particularly polar programs: Social economics and divergent settlement policies in postwar Scandinavia,” Review of Social Economy 70, no. 2 (2012): 164–80.

- 34. Einar Gerhardsen, Samarbeid og strid. Erindringer 1945–55 (Tiden norsk forlag, 1971), 130.

- 35. Lars Elenius, The Barents Region. A transnational history of subarctic Northern Europe (Cambridge University Press, 2015).

- 36. Olaf Foss, Steinar Johansson, Mats Johansson and Bo Svensson, “Regional policy at a crossroad: Sweden and Norway on different paths?” European Regional Science Association, (2002).

- 37. Einar Gerhardsen, Samarbeid og strid. Erindringer 1945–55, 130.

- 38. Steven Soderlind, “The Ascent of Regional Policy in Norway, 1945–1980” (Oslo: Norwegian Institute for Urban and Regional Research, 1999: 128): 10.

- 39. Even Lange, “ Styring og samarbeid,” https://www.norgeshistorie.no/velferdsstat-og-vestvending/1841-styring-og-samarbeid.html.

- 40. Høyre [The Conservative party], “Høyres hovedprogram 1965,” (NSD – Norwegian Centre for Research Data).

- 41. Ibid.

- 42. Steven Soderlind, “Particularly Polar Programs: Social economics and divergent settlement policies in postwar Scandinavia”: 164–80.

- 43. Ibid.

- 44. Håvard Teigen, “Distriktspolitikk gjennom 50 år.

- 45. Government, “About Norwegian regional policy,” (2015). https://www.regjeringen.no/en/topics/municipalities-and-regions/rural-and-regional-policy/om-regionalpolitikken/about-regional-policy/id2425726/.

- 46. The Conservative party, “Høyres stortingsvalgprogram 1988/89,” (NSD – Norwegian Centre for Research Data, 1988).

- 47. Government, “Helhetlig regionalpolitikk,” (1993). https://www.nb.no/items/URN:NBN:no-nb_digibok_2009082501017?page=7.

- 48. Government, “St prp nr 1 for budsjetterminen 1998.” https://www.regjeringen.no/no/dokumenter/st-prp-nr-1_1998-99/id202139/.

- 49. Government, “Regjeringens tiltredelseserklæring,” (Oslo, 2001). https://www.regjeringen.no/no/aktuelt/regjeringens_tiltredelseserklaering/id265184/.

- 50. Government, Meld. St. 13 (2012–2013), “Ta heile Noreg i bruk.” https://www.regjeringen.no/no/dokumenter/meld-st-13-20122013/id715615/?ch=1.

- 51. Gissur Erlingsson et al., “Centrum mot periferi? Om missnöje och framtidstro i Sveriges olika landsdelar,” (2021: 4): 74, https://www.ifn.se/media/a02dt3j0/2021-erlingsson-%C3%B6hrvall-lund%C3%A5sen-zerne-centrum-mot-periferi-om-missn%C3%B6je-och-framtidstro-i-sveriges-olika-landsdelar.pdf.

- 52. Jonas Stein, “The Striking Similarities between Northern Norway and Northern Sweden,” Arctic Review on Law and Politics 10 (2019): 81–82. https://arcticreview.no/index.php/arctic/article/view/1247/3113.

- 53. Elenius, The Barents Region. A transnational history of subarctic Northern Europe, (2015), 337.

- 54. Jakob Molinder et al., “What Can the State Do for You,” Scandinavian Journal of History 42, no. 3 (2017): 1–26. DOI: 10.1080/03468755.2017.1318337. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/03468755.2017.1318337.

- 55. Ibid.

- 56. Sejersted, Sosialdemokratiets tidsalder: Norge og Sverige i det 20. århundre, 246.

- 57. Ibid, 245.

- 58. Government, https://www.government.se/government-policy/sweden-and-nato/.

- 59. Molinder et al., “What Can the State Do for You.”

- 60. Jonas Stein, “The striking similarities between Northern Norway and Northern Sweden,” 89.

- 61. Ibid, 95.

- 62. Ibid, 98.

- 63. Ibid, 93.

- 64. Ibid, 94.

- 65. Ibid, 96.

Appendix

| Documents stemming from labour or bourgeois government | Quotes from public documents that indicate an active state role |

|---|---|

| Labour government document 1947 | “(to) raise the living conditions to equal level in the districts as in the towns” |

| Conservative party parliamentarian and future prime minister, John Lyng, Memoirs | As regards the first eight years after 1945: “… words and concepts like social coordinated regulation by the government – in contrast to private initiative, innovation and free enterprise – were in frequent use by all sides” |

| Conservative party programme 1965 | “The (Conservative) party is in favour of the construction of roads that can be open all the year, support of coastal merchant marines, and support of main flight routes” |

| Bourgeois Government document 1967 | “… a broad set of regional policies aimed at improving living conditions in areas of the country that had lagged behind the development in the rest of the country” |

| The Conservative party programme 1988 | “The overall goal of the Conservative party’s regional policies is to improve economic development, and safeguard settlement and living conditions in all parts of the country” |

| Labour government 1990 | “The main aim for comprehensive regional policies is to contribute to developing sustainable regions in all parts of the country, with balanced settlement patterns, and equity in employment, and in welfare services” |

| Bourgeois government 1997 | “(The government) aims to work throughout the country. Workplaces, funds, and (political) power ought therefore to be decentralised” |

| Bourgeois government 2001–2005 | “Well-intentioned economic development policies are good regional policies as well. Important fishing industries, the fish farming industry, agriculture, and the tourist industry, contribute to wealth creation in sparsely populated areas, and good living conditions throughout the country” |

| Labour government 2005–2012 | “(The government) will use the human and natural resources in all the country in order to make greatest possible national wealth, secure living conditions, and give everybody real freedom to settle wherever they want” |

| Bourgeois government 2013 | “We wish that people shall live throughout the country (…). We shall improve the growth potential and create opportunities for good living conditions over the entire country” |

| Bourgeois government 2017 | “(…) citizens in Norway are going to have equal living conditions wherever they live” |

| Bourgeois government 2017 | The government aims to make North Norway one of the most creative and sustainable in Norway. |

| Bourgeois government 2019 | “The government wishes to have thriving local communities throughout the country” |

Source: Own compilation of quotes from the documents in the Notes about regional policies.

| Established | Example** | Government | Kept by bourgeois government? |

|---|---|---|---|

1945 1989 |

Barnetrygd (Social security grant for children) Tillegg for barn i Finnmark og Nord Troms (additional grant for children in Finnmark and Nord Troms) |

Labour government Bourgeois government |

Yes |

1946 |

Husbanken [Housing bank] |

Labour government |

Yes |

1947 |

National budget |

Labour government |

Yes |

1947 2017 |

Statens lånekasse for utdanning (grants and loans for education) (Cancelling of student loans for new teachers in North Norway) |

Labour government Bourgeois government |

Yes |

1948 |

Fiskarbanken (loans and operating credit to fishing boats and fishing equipment) |

Labour government |

Yes |

1952 |

Development fund for North Norway |

Labour government |

Yes |

1952 |

Special tax rules |

Labour government |

Yes |

1960–1990 |

State run universities and university colleges*** |

Bourgeois and Labour governments |

Yes, and established some |

1968 |

SIVA (facilitates growth and development in industry and business) |

Bourgeois government |

Yes |

1964-today |

Moving government jobs from the Capital to the regions**** |

Labour and bourgeois governments |

Yes, and moved some |

*Regional policies in broad terms. Many policies mentioned are applicable throughout the country.

**Several of the examples have been amalgamated to other government units or policies later.

***Examples: Tromsø University 1968, University colleges in Bodø 1971, Alta 1973, Kautokeino 1989, and Narvik 1994.

****Examples: Branch of the National library (to Mo i Rana) 1989), Norges sjømatråd [Norwegian Seafood Council] (to Tromsø) 1991, Norges Brannskole (to Tjeldsund) 1993, Norsk Polarinstitutt [Norwegian Polar Institute] (to Tromsø) 1994–97.

Source: Own compilation from government documents and Stein (p. 92).