1 Introduction

Since Roald Amundsen’s first expedition through the Northwest Passage between 1903–1906 – and Adolf Erik Nordenskjold’s first attempt to traverse the Northeast Passage from 1878–1879, navigation in these waters has been debated.1 Passage rights for warships has been debated even more due to security implications for the coastal states bordering the passages.

Previous to the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), adopted in 1982, previous treaties operated with a three-mile-territorial-sea regime and the issue regarding navigation was less of a problem because most of the straits used for international navigation were wider than six nautical miles.2 That said, state practice was in favour of expanding the territorial sea before 1982.3 After expanding the territorial-sea regime, covering up to twelve nautical miles from the baseline, freedom of navigation was restricted. To compensate, the regime of transit passage through straits used for international navigation was established.

With ice-melting in the Arctic enabling new sailing routes, the debate has flourished once again. In 2020, High North Logistics at the Nord University reported in total 64 passages in the Northeast Passage compared to 37 in 2019.4 These statistics do not include warships. Statistics from Scott Polar Research Institute at the University of Cambridge show 32 warship transits in the Northwest Passage in 2019.5 Details of submarine transits are not included, but two were reported.6

Although warships enjoy both the right to innocent passage in territorial waters as well as the right to transit passage through straits used for international navigation, these rights are controversial and sometimes challenged. Navigation rights for warships are especially challenged in areas where the security interests of the coastal states bordering the passages is crucial to protect. On the other hand, freedom of navigation is highly valued. Navigation rights for warships in accordance with the law of the sea is about balancing these interests, hence the debate. To secure navigation rights for warships in the Northeast and Northwest Passages is therefore challenging due to security implications for both Canada and Russia. To demonstrate its security interests, Russia has established its most valuable strategic deterrence capacities in the Arctic, especially in connection with their naval bases on the Kola and Kamchatka peninsulas. Canada’s Nanisivik Naval Facility on Baffin Island, Nunavut, cannot be compared with the strategic importance of the Russian naval bases.

Navigation rights for warships was put to the test in the Northeast Passage when the French Navy conducted a transit with their new offshore support and assistance vessel Rhône in September 2018.7 There is no explicit information regarding whether the vessel coordinated its sailing plans with Russia, but the Russian News Agency Izvestia referred to the transit as “without warning”.8 Starting in Tromsø, Norway September 1, and ending in Dutch Harbor, Alaska September 17, the transit spurred Russia to set out stringent new rules for foreign warships in the Northeast Passage.9 The regulations contained special demands on construction, precautionary measures and requirements relating to safety of navigation and notification 45 days ahead for warships using the passage.10 However, the regulations have not been put into force, and it has been argued in legal theory that Russias’ primary intention with the draft was to send a strong political signal to deter further challenges to their claims in the passage.11

According to a July 16, 2021 press release, the U.S. Coast Guard vessel Cutter Healy conducted a transit through the Northwest Passage.12 However, this voyage occurred under the 1988 Canada-US Arctic Cooperation Agreement and did not engage with the dispute over the status of the waterway.13 In short, the cooperation agreement between the United States and Canada is an agreement to disagree, which is clearly stated in point 4 of the Agreement:

Nothing in this agreement of cooperative endeavour between Arctic neighbours and friends nor any practice thereunder affects the respective positions of the Governments of the United States and of Canada on the Law of the Sea in this or other maritime areas or their respective positions regarding third parties.14

In addition to security issues, the interests of protecting the marine environment and Indigenous peoples’ rights must be taken into consideration. Regarding the protection of the special environment in the Arctic, UNCLOS art. 234 on ice-covered areas is important. However, UNCLOS art. 236 makes an exception for warships due to their immunity, which will be discussed in connection with the environmental protection of ice-covered areas in point 2.5.

The main question in this article is whether or not the regime of transit passage for warships in straits used for international navigation will apply in the Northwest and Northeast Passages. Based on an analysis of the convention, this article aims to discuss which passage regime should apply for warships in both passages and the consequences for maritime operations in the area. Towards the end of the article, the perspectives of the United States and China are briefly introduced, as are the Canadian and Russian positions. Denmark, Norway, Iceland, Sweden, and Finland’s points of view are excluded due to the lack of official policy regarding their approach towards which navigational regime should apply in the passages.

2 Area of operation and legal framework

2.1 Some conditions in international law

Unlike Antarctica, the Arctic consists of an Arctic Ocean where the legal conditions are based on the Law of the Sea rather than an Antarctic Treaty.15 The Law of the Sea consists of custom, treaties, and international agreements. Navigational rights for warships in peace time is based on the rules of navigation regulated in UNCLOS.16 In addition, international custom and general principles of law recognized by nations should also be considered according to International Court of Justice (ICJ) statutes article 38(1).17 Judicial decisions and the writings of highly qualified publicists from various nations should also be taken into account.18 The Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties (1969), considered customary international law, should also be applied when interpreting the treaty (art. 31–33).19 Regarding the interpretation of warships’ navigational rights, the Corfu Channel case is also relevant.20

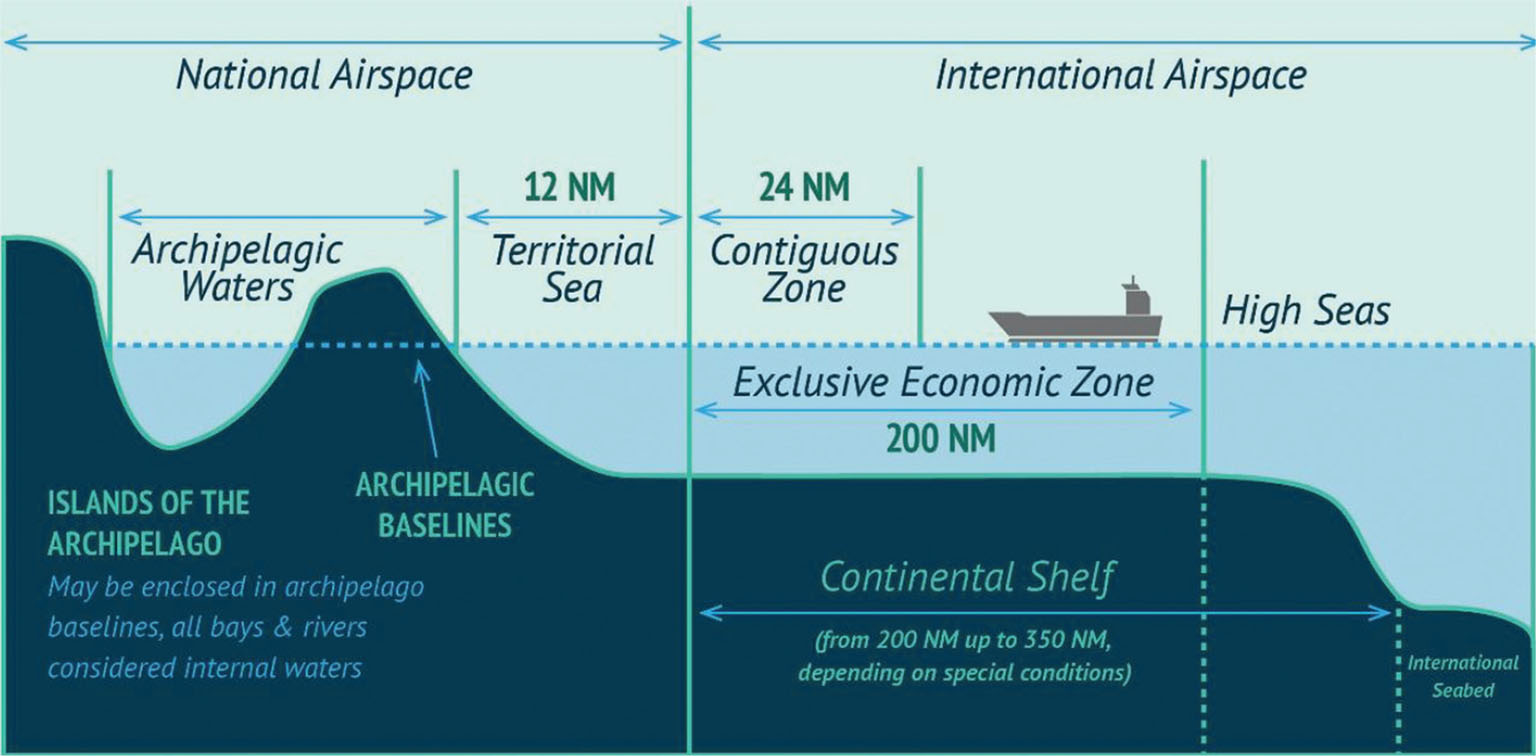

How to navigate in the Arctic depends on whether the waters are internal, territorial, exclusive economic zones or high seas, following the system found in UNCLOS and international customary Law of the Sea as illustrated in figure 1 below. In short, the Coastal State has less jurisdiction the further away from the baseline you get. The baseline is the starting point for measuring the legal zones, where the territorial sea starts based on the figure. Although “internal waters” are not illustrated in the figure, they are found in the area landward of the baseline, characterized as “Archipelagic waters” in the illustration. The legal background for measuring the different zones is important when discussing navigational rights because they lay out the jurisdiction for the coastal state to regulate navigation. In short, the further away from the baseline, the less jurisdiction to regulate the waters, with some exceptions. Transit passage for ships in straits used for international navigation is one of the exceptions where navigation rights triumph the normal regulation of zones bordering a coastal state. In the Northeast and Northwest Passages, the foundation for navigational rights is not clear due to disagreement on the interpretation of whether this exception should apply or not. Canada and Russia view the passages as “internal waters” subject to their exclusive jurisdiction, meaning the ability to regulate the area as land territory. The internal water-claim will be commented on in part 4. On the other hand, the United States views the passages as straits used for international navigation where the right to transit passage for all ships will apply. The US position will be commented on towards the end of the article.

Source: Batongbacal and Baviera (2013).

2.2 Geography

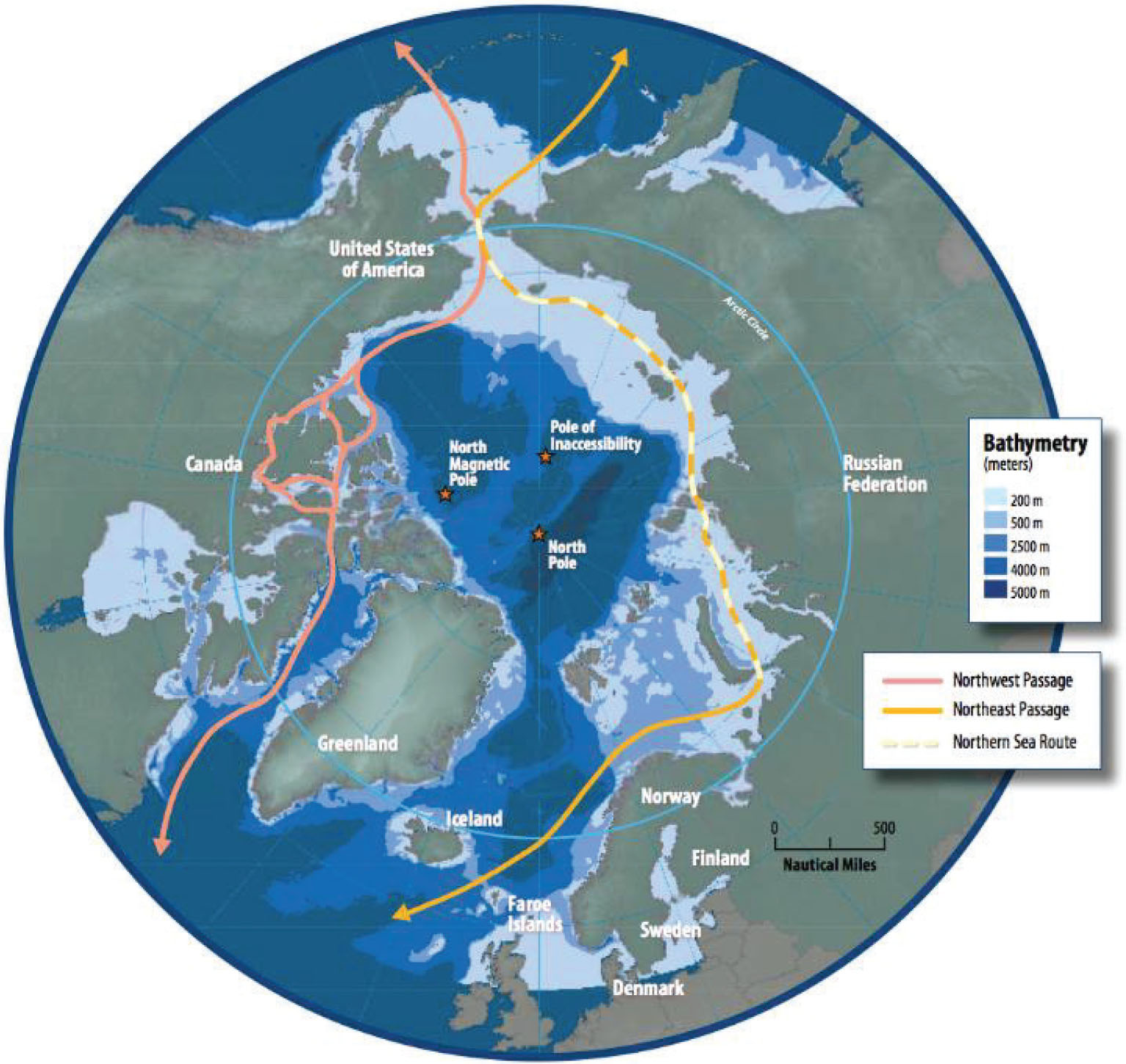

Before discussing the different views on navigational rights for warships in the passages, it is important to mention a few facts about geography and use of the passages since both play an important role in the interpretation. Geographical conditions lay down the basis for measuring the different legal zones in the Law of the Sea, where balancing the right of coastal states to protect themselves is set up against the freedom of navigation for all. Figure 2 shows a map of sailing routes relevant for interpretation.

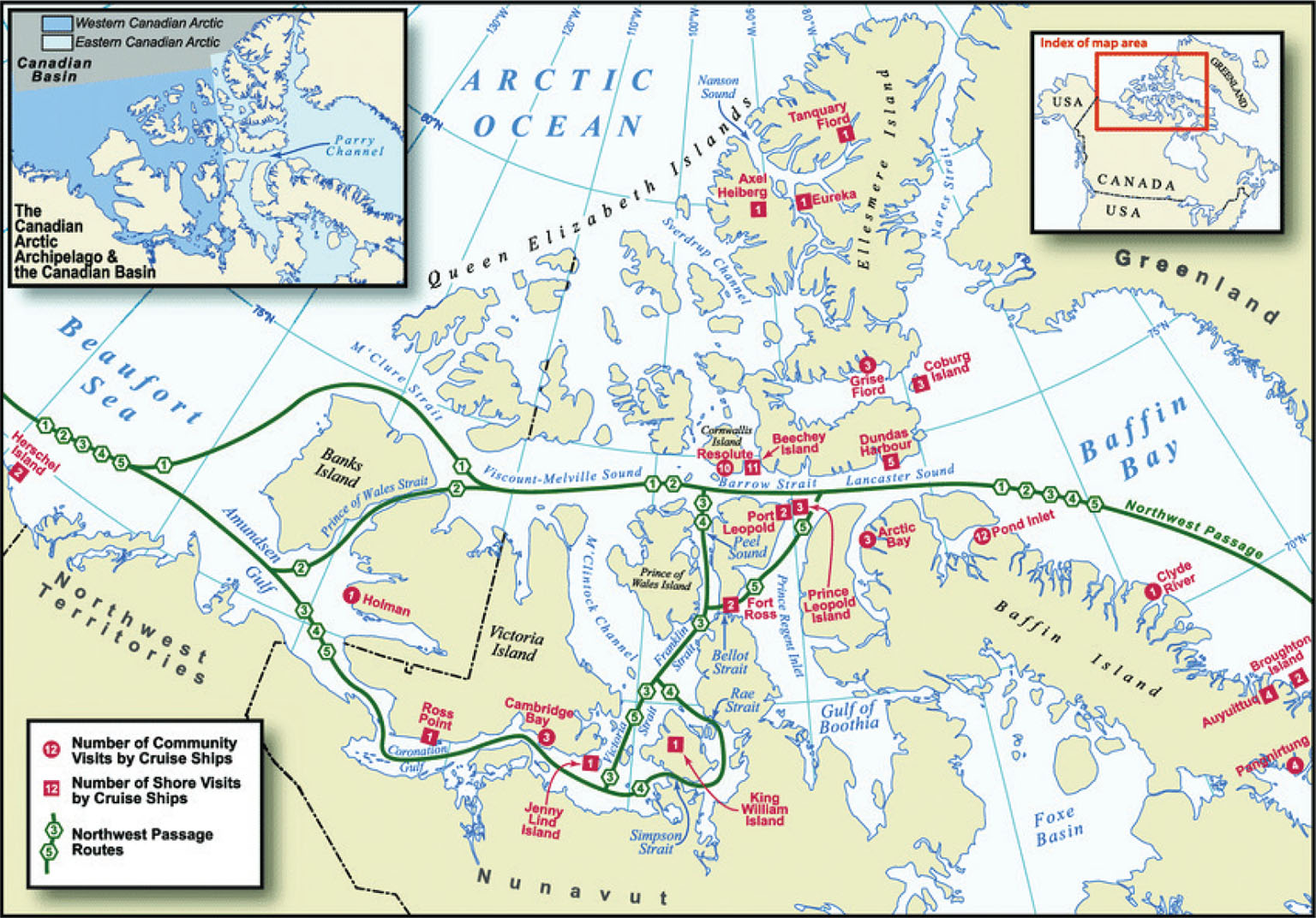

2.3 Different straits and waters relevant for interpretation

In the Northwest Passage, the straits, and waters relevant for interpretation depend on which route is chosen. Route 4 from Lancaster Sound – Barrow Strait – Prince Regent Inlet and Bellot Strait – Franklin Strait – Larsen Sound – Victoria Strait – Queen Maud Gulf – Dease Strait – Coronation Gulf – Dolphin and Union Strait – to Amundsen Gulf is the best route, according to a Chinese study from 2017.23 In the study, the different legs were analysed to find the best shipping route in the Northwest Passage. However, the “best” route will depend on ice conditions as well as the draft of the vessel. Although the study referred to suggests route 4, in practice this route can be quite shallow and has been poorly charted.

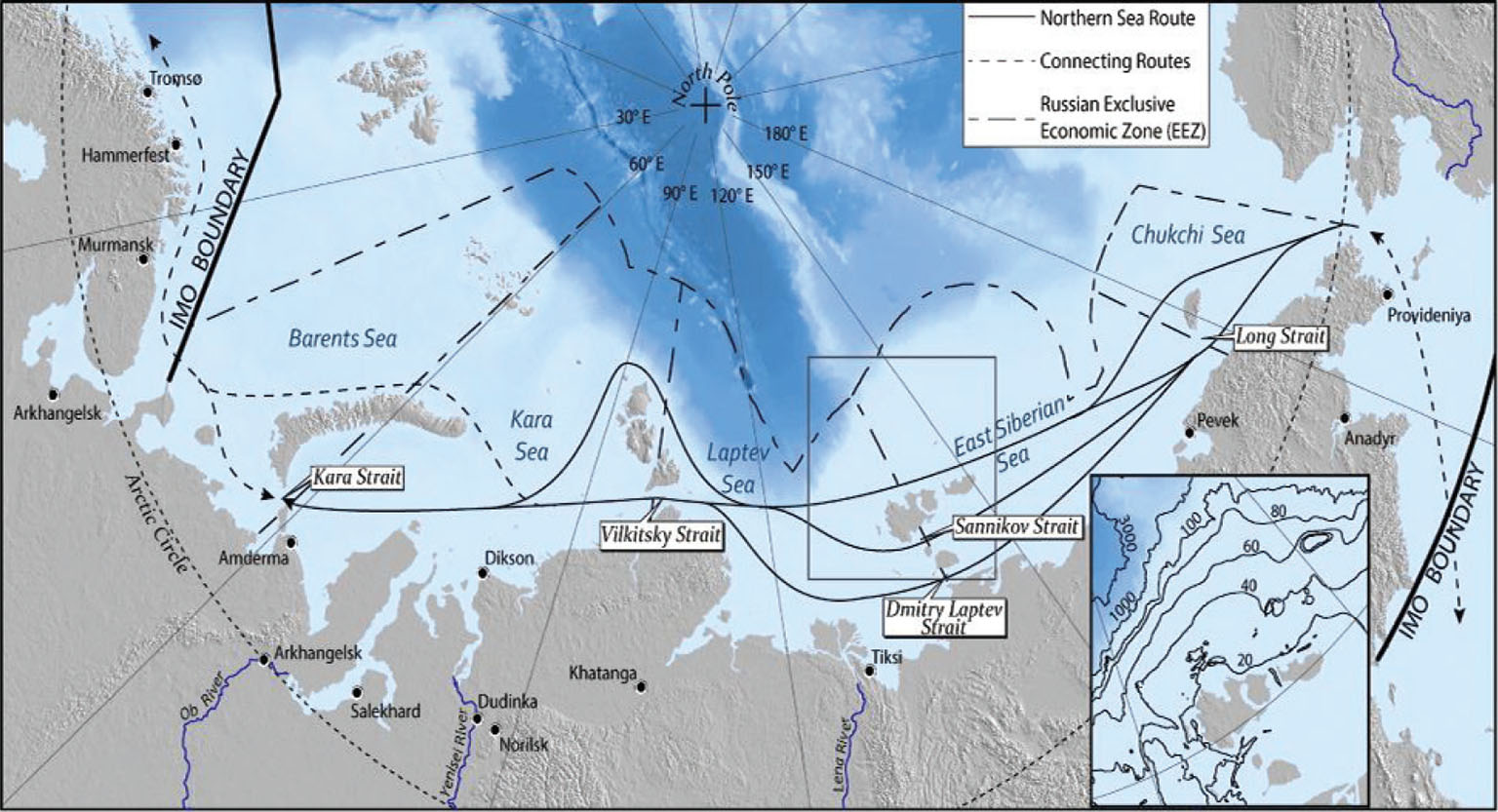

In the Northeast Passage, the Russian defined and legislated Northern Sea Route is the recommended sailing route and goes through the Bering Strait – Novaya Zhelaniya straits – Kara Gates Strait – Sannikov Strait and Vilkitskiy Strait.26 An alternative route to navigate further away from the Russian shore, is to navigate through Cape Zhelaniya and Cape Franz Joseph Land instead of through the Kara Gate, before going north of the cluster of Islands in the Kara and Laptev Sea instead of through the straits closer to shore, and continuing through the East Siberian Sea north of an island cluster before approaching Cape Dezhnev.27 By choosing this alternative route, legal disputes can be avoided.

In both passages, some straits are ice-covered and usually closed due to ice, and are only open a few months of the year. At the same time, the geography is different in the two passages. Although all the straits are referred to as straits, they are not necessarily used for international navigation, one of the key questions regarding establishing a set of navigational rights for warships applicable in the passages. In addition, it might be that the regime will change in the future due to a more ice-free Arctic Ocean.

2.4 Warships and its immunities

Before discussing the legal framework regarding navigation in the Northeast and Northwest Passages, the status of warships in the Law of the Sea is important to keep in mind. In this article, we follow the legal definition of “warship” established in UNCLOS art. 29:

a ship belonging to the armed forces of a State bearing the external marks distinguishing such ships of its nationality, under the command of an officer duly commissioned by the government of the State and whose name appears in the appropriate service list or its equivalent and manned by a crew which is under regular armed forces discipline.

Warships are also considered sovereign immune vessels, according to the wording in UNCLOS art. 32:

With such exceptions as are contained in subsection A and in articles 30 and 31, nothing in this Convention affects the immunities of warships and other government ships operated for non-commercial purposes.

The principle of immunity for warships together with the flag state principle indicates that warships enjoy sovereign immunity from interference by other nations’ authorities different from the flag state.28 Regarding navigation in the Northwest and Northeast Passages, this means that warships are immune from arrest, seizure, foreign taxes and forced pilotage, to mention a few. However, warships are required to comply with the coastal state’s laws and regulations within 12 nautical miles and follow the rules for innocent passage or transit passage.

At the same time, immunity affects the coastal states’ enforcement jurisdiction, as they lack enforcement instruments to exclude further passage. Coastal states may just notify the vessel to leave territorial waters or straits used for international navigation.29 On the other hand, the coastal state’s enforcement jurisdiction depends on the threat, which will be commented on in part 3 on transit passage.

2.5 Environmental protection of ice-covered areas

Today, navigating through the Arctic can be both harsh and dangerous, increasing the risk of accidents and potential environmental damage. Even though the passages are open, navigation through Arctic sea ice is difficult, especially because of the unpredictability of ice evolution for the following week.30 With the aim to protect the fragile Arctic environment while securing freedom of navigation, upholding navigational regulation in the Arctic is crucial, both for warships and commercial shipping. To balance navigational rights and protection of the environment, UNCLOS contains art. 234 to protect ice-covered areas. Article 234 gives the coastal state broader legislative mechanisms to regulate navigation. It is debatable whether the provisions in art. 234 apply in the territorial sea as well. This depends on whether we apply a strict or broad interpretation of the article. One argument against applying it in the territorial sea is that it is not regulated in the part regarding the territorial sea in UNCLOS. On the other hand, why should a coastal state have broader regulatory powers in the EEZ than in its own territorial waters?

At the same time, article 236 has an exception for warships due to their status as sovereign immune vessels. Article 236 states that the regulations: “do not apply to any warship, naval auxiliary, other vessels or aircraft owned or operated by a State and used, for the time being, only on government non-commercial service”. The latter is especially important in relation to Russia’s view on warships’ navigational rights in the Northeast Passage. In 2013, Russia made new domestic legislation in the Northeast Passage, but it does not regulate warships.31 Whether this legal gap was intentional or not is not easy to say, but Russia suggested regulating navigational rights for warships in the Northeast Passage after France navigated through the passage in 2018 as mentioned in the introduction. That Russia did not pass this new legislation might have something to do with their interests in the Law of the Sea providing predictability in the Arctic. After all, Russia has all the lengthiest coastline bordering the Arctic.

3 The internal water-claim

3.1 Illegal use of straight baselines

According to UNCLOS, internal waters are regulated by art. 8 which states that waters on the “landward side” of the baseline shall be considered as part of the “internal waters” of a state.

The core of the disagreement on the interpretation regarding the legal status over the waters bordering the Northeast and Northwest Passages is the Canadian and Russian use of straight baselines to determine “internal waters”. The baseline is the starting point for measuring the other legal zones in accordance with the system in UNCLOS. Prior to claiming a right to areas beyond the baseline, it is crucial to stipulate the outer limits of the baseline. Canada and Russia have chosen to build their internal water-claim on the establishment of straight baselines, resulting in the passages being completely under their exclusive jurisdiction. This claim has been challenged by the United States, which will be commented on in part 5.

Straight baselines are regulated in UNCLOS art. 7 and are a relatively new phenomenon in international law, even though Norway established straight baselines in 1869, and France in 1888.32 In a decision from the International Court of Justice (ICJ) in the Fisheries Case from 1951, the court stated conditions for measuring straight baselines:

Where a coast is deeply intended and cut into, as that of Eastern Finnmark, or where it is bordered by an archipelago such as the “skjærgaard” along the western sector of the coast here in question, the base-line becomes independent of the low-water mark, and can only be determined by means of geometrical construction.33

In comparison with the Northwest and Northeast Passages, they cannot be said to consist of coasts “deeply intended and cut into” nor an “archipelago”. Use of straight baselines based on UNCLOS art. 7 is therefore illegal based on both the wording of the article, and with support in the Fisheries Case.

3.2 Claim regarding “historic titles”

Canada and Russia also claim the waters bordering the passages to be internal based on “historic titles”. UNCLOS recognizes “historic titles” in relation to bays in art. 10 and delimitation of the territorial sea between States with opposite or adjacent coasts in art. 15. In the case between the Philippines and China from 2017, The Permanent Court of Arbitration found that any previous “historic titles” apart from those explicitly mentioned in the convention should be superseded.34

Since the passages cannot be characterized as either bays or sea between States with opposite or adjacent coasts, the historic title-claim cannot be taken into consideration in the Northeast or Northwest Passages.

4 Transit passage in straits used for international navigation

4.1 Ensuring freedom of navigation in straits traditionally used for international navigation

Transit passage in straits used for international navigation aims to balance the right to freedom of navigation with coastal state sovereignty over its waters bordering a strait following the classification of legal zones in UNCLOS.35

Historically, the right of transit passage depended on whether the waters were considered high seas or territorial sea.36 The regime under customary law and the Territorial Sea Convention operated with the rules of innocent passage in straits bordering territorial waters, and full freedom of navigation in straits with High seas or Exclusive Economic Zones corridors in the middle (straits wider than 24 NM). Like the regime on the right to innocent passage in the territorial sea, transit passage for warships in straits used for international navigation has been controversial, especially in relation to the Kerch strait end the strait of Hormuz, to mention two cases. However, it is undisputable that the right of transit passage applies to all ships and aircraft, both military and commercial.37 In the Corfu Channel case from 1949, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) established that as a matter of customary law, warships had the right to innocent passage through international straits, which could not be suspended by the coastal state.38 Submarines are also allowed to transit submerged recognized in accordance with the wording “incident to their normal mode of continuous and expeditious transit” and the travaux préparatoires of UNCLOS III.39

Today, the core of the controversy regarding warships in transit passage through straits used for international navigation lies in the ability of the coastal state to suspend the right to navigation to protect its security interests up against freedom of navigation for all. Transit passage in straits used for international navigation is regulated in UNCLOS Part III, Section 2, art. 37 and following. The key to establishing a regime for transit passage is based on having a strait and the following conditions: 1) it needs to connect either High Seas or Exclusive Economic zones to each other and, 2) be used for international navigation.40

4.2 Geographical condition

Straits are not defined in UNCLOS, nor in other conventions, but the term denotes its ordinary meaning: a narrow natural passage or arm of water connecting two larger bodies of water.41 Whether or not rules of transit passage apply to a strait depends on the status of the waters bordering the strait.42 To establish the rules of transit passage, the strait must be “between one part of the high seas or an exclusive economic zone and another part of the high seas or an exclusive economic zone”.43 The wording indicates a geographic test. The Northeast Passage connects the Arctic Ocean between the Barents Sea and the Chukchi Sea through the straits of Dmitry, Laptev and Sannikov, thus fulfilling the geographic test.44 The Northwest Passage connects the Baffin Bay/Dais Strait with the Beaufort Sea, fulfilling the geographic test if it is viewed as a series of straits used for international navigation.

4.3 Condition for use

Our next task is therefore to investigate what lies in the condition “used for international navigation”.45 The wording is ambiguous regarding whether it needs to be used right now, or if this can change in the future. In other words, the question is if potential use and not historic use will qualify for an article 37-strait. If the status of a strait can change due to climate change and melting ice in the Arctic, it is easier to argue in favour of applying the rules for transit passage in both the Northwest and Northeast Passages. In relation to “historic use”, explicitly mentioning such use as a condition was excluded despite a suggestion from Canada in a working paper during the process leading up to UNCLOS.46 The exclusion of the wording ‘historic use’ in the treaty is an argument in favour of not using “historic use” as a condition to establish an article 37-strait.

It is also disputed if art. 37 requires a functional use-test at all.47 In the Corfu Channel Case from 1949, where two British warships struck Albanian mines, the International Court of Justice recognized that the Corfu Channel was a strait used for international navigation.48 Even though the court argued in favour of the conditions being met, the application of the functional test left uncertainty due to the lack of elaboration of the minimum criteria regarding use.49 It is also questionable whether the Corfu Channel Case should be given too much weight, especially since UNCLOS and art. 37 were adopted with the decision from the case in mind without clarifying the question of use. State practice shows that potential use is not sufficient to turn a geographical strait into a juridical one.50 With UNCLOS not clarifying the threshold for use and State practice concluding the opposite, it is also hard to argue in favour of potential use as a criterion for an article 37-strait.

In conclusion, we must fall back on geographical conditions, which may be far more important than actual use. Falling back on geographical conditions is also in line with the reasoning behind measuring the different legal zones, where such conditions lay the foundation for jurisdiction. In the matter of the Northwest Passage, it is an efficient route to navigate from the Atlantic to the Pacific Ocean despite challenges related to ice conditions for most of the year. The same can be said regarding the Northeast Passage as the shortest route between Europe and Asia.

4.4 Stipulations applicable to article 37-straits

If the above-mentioned conditions are met, the strait is governed by transit passage in accordance with rules for navigation in UNCLOS art. 38 and following. In transit passage, there is no criteria of “innocence”. However, both warships and military aircraft must refrain from any threat or use of force against the States bordering the straits and activities that might violate the principles of international law, UN Charter included.51 If warships or military aircraft constitute a threat or use force, the coastal state can hamper passage until the conditions for transit passage are re-established.

UNCLOS art. 39 establishes several duties for warships and military aircraft. However, these duties are not conditions for transit passage; they constitute an obligation ancillary to it.52 Similar to the regime of innocent passage, navigation and overflight must be “continuous and expeditious”, meaning, in short, no stopping, shooting or anchoring.53 Warships and military aircraft must refrain from any activities other than those incidental to their “normal modes of continuous and expeditious transit” with the exception of activities rendered necessary by force majeure or distress.54

Transit passage cannot be suspended or hampered, and the coastal state must notify users of any danger to navigation or overflight within the strait or over it.55 Warships and military aircraft must at the same time obey laws and regulations to secure safety of navigation.56

4.5 Special rules for submarines and military aircraft

The most important difference for warships in transit passage through straits used for international navigation applies to submarines, which can be submerged while conducting passage.57 In comparison to military aircraft, the most important difference is the allowance of overflight and landing by jet planes on, for instance, an aircraft carrier. If a passage is characterized as an international strait used for international navigation, the right to overflight will be intact and fighters will be able to operate in “normal mode”.58 Transit passage is therefore of great importance to military aircraft.59 Even though military aircraft enjoy the right to transit passage in straits used for international navigation, they must observe international rules and regulations to secure safety of navigation while conducting passage.60

4.6 Enforcement mechanisms for the coastal state

Warships and military aircraft are subject to UNCLOS art. 42(5). The flag State of warships and military aircraft should bear international responsibility for any loss or damage resulting from a breach of the coastal state’s laws and regulations. However, the coastal state may not hamper their transit passage unless they pose a threat.

5 Different views on the legal status

5.1 Consequences on navigational rights for warships based on Canadian and Russian perspectives

Statements regarding the legal status of the passages differ substantially between the different stakeholders in the Arctic. Both Russia and Canada are coastal states bordering the passages and claim the waters to be internal waters based on the concept of “historic titles” explained in point 3.2.

Canada claims full sovereignty over the Northwest Passage. In 1985, Canada drew straight baselines around its archipelago, and claims the waters in the Northwest Passage fall within its internal waters.61 If the Northwest Passage is recognized as internal waters, no passage rights will exist for warships at all. Canada has also stressed the views of its Indigenous peoples, who support the official Canadian view that the passage falls within its internal waters.62

Although internal waters based on straight baselines will give the coastal state exclusive jurisdiction, warships enjoy the right to innocent passage in Russian territorial waters if such passage is in line with “generally-recognized principles and norms of international law, international treaties of the Russian Federation, and also legislation of the Russian Federation”.63 Like Canada, Russia has adopted straight baselines along their Arctic coast, which has led to international objections.64

Legal scholars have debated whether the Northeast Passage constitutes a strait used for international navigation or not.65 Apart from some of the individual straits enclosed by straight baselines drawn by Russia in 1985, legal scholars have argued that it is doubtful whether the straits are actually used for international navigation, stressing the mere “handful” of sailings through the passage.66 Due to uncertainty regarding actual use as a condition, the conclusion is to fall back on the geographical condition discussed in point 4.3 about the threshold for defining “used for international navigation”.67

5.2 The American perspective

The United States does not agree with the Canadian and Russian approach. The official position of the United States government is that the Northwest Passage is a strait between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, running through the ice-packed Arctic and therefore constitutes one of the “straits which are used for international navigation” under UNCLOS art. 37.68 Although the United States has yet to sign UNCLOS, they view the treaty as customary law. The dispute between the United States and Canada on this matter led to the bilateral Agreement on Arctic Co-operation, which obliges consent from Canada before conducting passage by American icebreakers.69 In return, they agreed to disagree in order to preserve the views and rights of both parties.70

5.3 The Chinese perspective

China has an ambition to build a “Polar Silk Road” in their five-year-plan from 2021–2025.71 Thus far, we have no information about what we can expect from China in relation to navigation for warships and military aircraft in the Northeast and Northwest Passages in the future.

However, China’s domestic regulation on the territorial sea is worth mentioning. It specifies that “No foreign vessels for military use and no foreign aircraft may enter China’s territorial sea and the air space above it without the permission of the government of the People’s Republic of China”.72 China’s domestic legislation and the Chinese view on “historic titles” in light of the South China Sea Arbitration between China and the Philippines, might make it hard to argue against Canada and Russia regarding navigational rights in the passages.73 China’s problem relates to their view on “historic titles” in the South China Sea, similar to the argument presented by Canada and Russia regarding the Northeast and Northwest passages. Like Canada and Russia, China wishes to establish straight baselines in the South China Sea but lacks support in international law. Without sovereignty, historic rights may be granted, but with a high threshold for evidence. Historic rights should reflect a continuous, undisrupted and long-established situation, i.e. fishing rights.

In the Chinese Arctic Policy from 2018, China views herself as a “Near-Arctic State”.74 In the policy, China views Arctic shipping routes as governed by UNCLOS, but states that “the freedom of navigation enjoyed by all countries in accordance with the law and their rights to use the Arctic shipping routes should be ensured”. How these rights should be ensured, is not explained further. Based on China’s interest in building a “Polar Silk Road”, they might push for freedom of navigation through the passage in the future. China also views the Arctic as a mankind’s common heritage, an approach not shared by Russia.75

6 Moving forward

Compared to other areas, the disagreement over the Northeast and Northwest Passages is based on different views regarding the interpretation of navigation rules, not who is the legitimate coastal state bordering the straits. Based on an interpretation of the different navigation rules, both passages should be characterized as straits used for international navigation. Firstly, the passages clearly meet the geographical condition to establish an article 37-strait in accordance with UNCLOS. Secondly, Canada and Russia’s internal water-claims lack support in international law, regardless of whether these claims are based on historic titles or the use of straight baselines enclosing the passages.

However, UNCLOS art. 234 on ice-covered areas might well be used to regulate commercial shipping through the passages, but it cannot apply to warships due to their immunity stated in art. 236.

Nevertheless, at present there is a great deal of riskiness involved in conducting military maritime operations in the passages due to the different approaches regarding the legal regime on navigation. With such uncertainty regarding navigation rights in both the Northeast and Northwest Passages, Incident at Sea-agreements are crucial to avoid conflict escalation. Communication between nations is key in this respect. In the Northwest Passage, Canada and the United States have taken a position through the 1988 Canada-US Arctic Cooperation Agreement where they agree to disagree on the legal status of the waters, helping to lower this tension.

Such cooperation agreements are, in contrast to Freedom of navigation operations, means to avoid conflict escalation. Freedom of Navigation Operations (FONOPs) based on the American model might be a way to express a political point of view using military means. Expressing their views through other diplomatic channels might be a better solution in the Arctic due to the agreement on jurisdiction, despite different views regarding the interpretation of UNCLOS. It is also of great importance to keep up the good work regarding peaceful exploitation in the region in other fields, which again is an argument against the use of FONOPs in the passages to avoid further tension. If the goal is to establish freedom of navigation for all, it is also important to keep in mind the immunity of warships. Warships are, compared to commercial ships, not denied navigational rights due to their immunity, except when entering internal waters. In other words, if the goal is to secure the right of navigation for commercial ships as well, diplomatic channels might be a better solution.76

However, the discussion about which navigational regime to apply might change in the future due to changing ice conditions and a more open Arctic Ocean. Climate change might move the discussion from navigational rights for warships to responsibility in case of any incidents or accidents among warships with an impact on the fragile environment in the Arctic.

NOTES

- 1. Susan Barr, “Roald Amundsen,” in Store norske leksikon (snl.no, 2019) https://snl.no/Roald_Amundsen (accessed December 1, 2021); University Library at the University of Tromsø, “The Northeast Passage,” (The Northern Lights Route, 1999), https://www.ub.uit.no/northernlights/eng/northeast.htm (accessed December 1, 2021).

- 2. For example, the strait of Hormuz (29 nautical miles), the Bering Strait (44 nautical miles).

- 3. Kai Trümpler, Article 3–8 in United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea – A Commentary, ed. Alexander Proelss w. others (München: Verkag C. H. Beck, 2017), 34–96, 38.

- 4. Centre for High North Logistics, NSR Shipping Traffic – Transit Voyages in 2020, Nord University (Under “Maps”, 2021), http://www.chnl.no/ (accessed July 7, 2021).

- 5. R. K. Headland and colleagues, Transits of the Northwest Passage to end of the 2019 Navigation Season, Scott Polar Research Institute at the University of Cambridge (Cambridge, 2020), https://www.spri.cam.ac.uk/resources/infosheets/northwestpassage.pdf

- 6. Ibid.

- 7. Atle Staalesen, “Russia sets out stringent new rules for foreign ships on the Northern Sea Route,” Arctic Today (arctictoday.com), March 8 2019, https://www.arctictoday.com/russia-sets-out-stringent-new-rules-for-foreign-ships-on-the-northern-sea-route/ (accessed July 7, 2021).

- 8. Kozachenko, Alexey w. others, “Холодная волна: иностранцам создали правила прохода Севморпути”, March 6 2019, https://iz.ru/852943/aleksei-kozachenko-bogdan-stepovoi-elnar-bainazarov/kholodnaia-volna-inostrantcam-sozdali-pravila-prokhoda-sevmorputi (accessed November 25, 2021).

- 9. Supra note 7.

- 10. Jan Jakub Solski, “The Northern Sea Route in the 2010s: Development and Implementation of Relevant Law,” Arctic Review on Law and Politics 11 (2020), 4.2.

- 11. Jan Jakub Solski, “Navigational rights of warships through the Northern Sea Route (NSR) – all bark and no bite?”, The NCLOS blog, posted May 31 (2019), https://site.uit.no/nclos/2019/05/31/navigational-rights-of-warships-through-the-northern-sea-route-nsr-all-bark-and-no-bite/ (accessed November 28, 2021).

- 12. United States Coast Guard, “Coast Guard icebreaker departs for months-long Arctic deployment, circumnavigation of North America,” Press release July 16 (2021). https://content.govdelivery.com/accounts/USDHSCG/bulletins/2e87c45 (accessed July 31, 2021).

- 13. The 1988 Canada-US Arctic Cooperation Agreement, https://www.treaty-accord.gc.ca/text-texte.aspx?id=101701 (accessed November 29, 2021).

- 14. Ibid.

- 15. The Antarctic Treaty (1959), available on the homepage of the Secretariat of the Antarctic Treaty: https://www.ats.aq/index_e.html (accessed November 28, 2021).

- 16. United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (1982), UNCLOS.

- 17. Statute of the International Court of Justice, (1945).

- 18. Aldo Zammit Borda, “A Formal Approach to Article 38(1)(d) of the ICJ Statute from the Perspective of the International Criminal Courts and Tribunals,” European Journal of International Law 24, no. 2 (2013), https://doi.org/10.1093/ejil/cht023.

- 19. Vienna Convention on the Law of the Treaties, (1969).

- 20. The Corfu Channel Case (United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland v. People’s Republic of Albania), Judgement of December 15 (1948), I.C.J. Reports 1949, 244.

- 21. Aileen S. P. Baviera and Jay Batongbacal, The West Philippine Sea: The Territorial and Maritime Jurisdiction Disputes from a Filipino Perspective, Institute for Maritime Affairs and Law of the Sea at the University of the Philippines (2013), https://www.academia.edu/28391794/West_Philippine_Sea_Territorial_and_Maritime_Juridiction_Disputes_from_a_Philippine_Perspective._A_Primer.

- 22. Harder, Susie, illustration for the Arctic Council.

- 23. Xing-he Liu, Long Ma, Jia-yue Wang, Ye Wang, Li-na Wang, “Navigable windows of the Northwest Passage,” Polar Science 13 (2017), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polar.2017.02.001.

- 24. Ibid.

- 25. Protection of the Arctic Marine Environment, Northern Sea Route Shipping Statistics, Northern Sea Route Shipping Statistics (pame.is) (accessed July 31, 2021).

- 26. Ibid.

- 27. Ibid.

- 28. UNCLOS art. 32, 58(2), 95 & 236.

- 29. UNCLOS art. 30.

- 30. Interview with Hervé Baudu, Malte Humpert, “A New Dawn for Arctic Shipping – Winter Transits on the Northern Sea Route,” High North News (highnorthnews.com), January 19 2021, https://www.highnorthnews.com/en/new-dawn-arctic-shipping-winter-transits-northern-sea-route

- 31. Solski, “The Northern Sea Route in the 2010s: Development and Implementation of Relevant Law.”

- 32. Kai Trümpler, Article 3–8 in United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea – A Commentary, ed. Alexander Proelss w. others (München: Verkag C. H. Beck, 2017), 34–96, 67.

- 33. Fisheries Case (United Kingdom v. Norway), Judgement of December 18 (1951), I.C.J. Reports 1951, 116, 128–129.

- 34. See para. 238(a) in The South China Sea Arbitration (The Republic of the Phillippines v. The People’s Republic of China), No. 2013–19 PCA Cases 479 (Permanent Court of Arbitration July 12, 2016). In addition, Sophia Kopela, “Historic Titles and Historic Rights in the Law of the Sea in the Light of the South China Sea Arbitration,” Ocean Development & International Law 48:2 (2017), https://doi.org/10.1080/00908320.2017.1298948.

- 35. Figure 2, supra note 22.

- 36. Robin Churchill and Vaughan Lowe, The Law of the Sea, 3rd ed. (Manchester, 1999), 102; 1958 Territorial Sea Convention art. 16(4).

- 37. Ibid., 109.

- 38. Ibid., 102; The Corfu Channel Case (United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland v. People’s Republic of Albania).

- 39. Ibid.; UNCLOS art. 39(1), c.

- 40. UNCLOS art. 37.

- 41. Churchill, The Law of the Sea, 102.

- 42. Ibid.

- 43. Ibid.

- 44. Supra note 25.

- 45. Ibid.

- 46. Myron H. Nordquist and Neal R. Grandy, Shabtai Rosenne and Alexander Yankov (eds.), United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, 1982: A Commentary, vol. 4 (1990), 113–116.

- 47. Note on “The Potential-Use Test and the Northwest Passage,” Harvard Law Review 133 (2020), https://harvardlawreview.org/2020/06/the-potential-use-test-and-the-northwest-passage/ (accessed July 7, 2021).

- 48. The Corfu Channel Case (United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland v. People’s Republic of Albania), 28.

- 49. Note on “The Potential-Use Test and the Northwest Passage.”, B. The Corfu Channel Case.

- 50. Bing Bing Jia, “Article 34–45,” in United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea – A Commentary, ed. Proelss Alexander with others (München: Verkag C. H. Beck, 2017), 292.

- 51. Churchill and Lowe, The Law of the Sea, 107; UNCLOS art. 39(1), b; UN Charter art. 2(4).

- 52. Churchill and Lowe, The Law of the Sea, 107.

- 53. UNCLOS art. 38(2).

- 54. UNCLOS art. 39(1), c.

- 55. UNCLOS art. 44.

- 56. UNCLOS art. 39(2).

- 57. UNCLOS art. 39(1), c.

- 58. UNCLOS art. 38(2).

- 59. Churchill and Lowe, The Law of the Sea, 109.

- 60. UNCLOS art. 39(3).

- 61. ICC Canada, “Inuit and Canada Share Northwest Passage Sovereignty – ICC Canada President,” news release, May 8 (2019), https://www.inuitcircumpolar.com/press-releases/inuit-and-canada-share-northwest-passage-sovereignty-icc-canada-president/ (accessed July 31, 2021).

- 62. Note on “The Potential-Use Test and the Northwest Passage.”

- 63. William E. Butler, Russian Law, 3 ed. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), 698.

- 64. Michael Reisman and Gayle Westerman, “Straight Baselines in International Maritime Boundary Delimitation,” St. Martin’s Press (1992).

- 65. Churchill and Lowe, The Law of the Sea, 106.

- 66. Ibid.

- 67. UNCLOS art. 37.

- 68. Note on “The Potential-Use Test and the Northwest Passage.”

- 69. Churchill and Lowe, The Law of the Sea, 106.

- 70. J. Ashley Roach, United States responses to excessive maritime claims/J. Ashley Roach and Robert W. Smith, ed. Robert W. Smith and J. Ashley Excessive maritime claims Roach, Publications on ocean development; v. 27. (The Hague; Boston: Cambridge, MA: M. Nijhoff Publishers; Sold and distributed in the U.S.A. and Canada by Kluwer Law International, 1996).

- 71. Reuters Staff, “China pledges to build ‘Polar Silk Road’ over 2021–2025,” (Reuters.com, March 5, 2021), https://www.reuters.com/article/us-china-parliament-polar/china-pledges-to-build-polar-silk-road-over-2021-2025-idUSKBN2AX09F?il=0 (accessed July 31, 2021).

- 72. Law of the People’s Republic of China on the Territorial Sea and the Contiguous Zone (1982).

- 73. The South China Sea Arbitration (The Republic of the Phillippines v. The People’s Republic of China), No. 2013–19.

- 74. The State Council Information Office of the People’s Republic of China, China’s Arctic Policy 2018, https://eng.yidaiyilu.gov.cn/zchj/qwfb/46076.htm (accessed November 28, 2021).

- 75. Tianming Gao & Vasilii Erokhin, “China-Russia collaboration in arctic shipping and maritime engineering”, The Polar Journal 10 no. 2 (2020), https://doi.org/ 10.1080/2154896X.2020.1799612.

- 76. Cornell Overfield, “FONOP in Vain: The Legal Logics of a U.S. Navy FONOP in the Canadian or Russian Arctic”, Arctic Yearbook (2021): 1–18.