1 Introduction

The Arctic has attracted growing interest from academics, politicians, and business representatives since it was established as an international zone of peace following the end of the Cold War. Since then, the region has been characterized by cooperative institutions, forming a complex picture of transnational collaboration.1 Along with increased interest in the Arctic, there has also been significant growth in the number of conferences attending to Arctic issues. Yet, these conferences have received far less attention in academic discussions on Arctic governance than institutions, organizations, or states.2 This article addresses this shortcoming in the literature.

Firstly, the article casts light on the development of the Arctic conference sphere, by presenting an historical overview of arenas attending to Arctic issues established since the 1960s. Secondly, the expansion in the number of Arctic conferences is linked to processes and central developments within Arctic affairs, to demonstrate the significance of conferences within governance structures. Thirdly, the need for information exchange and communication among various stakeholders in the Arctic has become more pressing as different issue areas are becoming increasingly interlinked,3 and this article illustrates how “hybrid” policy-science-business conferences helped fill this demand within Arctic governance.

Accordingly, the article devotes particular attention to the two largest conferences in the region: Arctic Frontiers and Arctic Circle Assembly. They are examples of conferences created with the purpose of bringing science into the decision-making process, and advancing the science-policy-business interplay. The article sheds light on why these conferences were developed and the main aims of the organizers. From this, by examining connections between events taking place within Arctic governance, topics on the regional agenda, and themes addressed at conferences, the article displays the broader significance of conferences for processes and developments within Arctic policy. I draw on the epistemic community framework – to cast light on a central conference participant group and the role of conferences in implementing the policy-science-business interplay, and I also look to the literature on regime complexes to situate conferences within broader governance structures.

2 Conceptual framework and methods

2.1 The Earth System Governance literature and regime complexes

Arctic governance has been described as a “mosaic of issue-specific arrangements”,4 a “patchwork of formal and informal arrangements operating on different levels”,5 and a “set of interlinked and overlapping policy fields”.6 For the main purpose of this article – to examine the expansion of conferences within Arctic governance – I find support in research conducted on regime complexes within the Earth System Governance literature. The underlying conviction of these scholars is that international institutions do not exist in a void, and cannot be analyzed without considering the complex web they operate within, which has become referred to as governance architectures.7,8,9,10 A governance architecture is an overarching system consisting of building blocks (such as international institutions/regimes, transnational institutions, and networks), structural features (for example interlinkages between institutions, regime complexes, and degrees of fragmentation), and policy responses.11

This article zooms in on one of the structural features – a regime complex12 – which is understood as: “a network of three or more international regimes that relate to a common subject matter; exhibit overlapping membership; and generate substantive, normative, or operative interactions recognized as potentially problematic whether or not they are managed effectively”.13 From this, a regime complex can be usefully conceptualized as an open system that is held together enough to be recognizable, but which is not completely detached from the rest of global governance.14 Institutions within the regime complex should be considered as a set rather than as unconnected units or a cohesive block.15

This definition is applicable to the Arctic regime complex, which comprises several treaty regimes that deal with a variety of issues: the oceans, shipping, fisheries, flora and fauna, climate change, and the environment. The Arctic regime complex contains intergovernmental and inter-parliamentary organizations, including the Nordic Council of Ministers, the West Nordic Council, the International Maritime Organization, the UN Environmental Program, and the UN Development Program. In addition, non-state actors and international non-governmental organizations include the International Arctic Science Committee, the International Arctic Social Sciences Association, the International Union for Circumpolar Health, and the Northern Forum.

It is evident from the above that elements within the Arctic regime complex attend to overlapping issue areas and display overlapping membership. For example, the Arctic Science Ministerial, the Arctic Council Science Agreement, and the International Arctic Science Committee are all concerned with science. The Arctic states are members of most of the regimes within the Arctic governance architecture, and most of the above-mentioned organizations are observers to the Arctic Council and frequently attend conferences. The Arctic Council – a hub within the Arctic regime complex – is a central forum for engagement among the Arctic states, Indigenous peoples, and several observer non-Arctic states and organizations. However, the observers are excluded from participating in the discussions and decision-making of the Arctic Council.16 This opens a window for conferences as useful supplements for a broader pool of stakeholders to have their voices heard, display their work, and argue for their legitimacy in the region, to reach a broader audience. Accordingly, I argue that conferences function as additional links among the other units in the Arctic regime complex.

2.2 The Epistemic Community Framework

In addition to examining how conferences fit within the broader Arctic governance structure, this article also sheds light on how conferences have developed as central arenas in the Arctic for bringing science into the policy-making process. For this purpose, I draw on the epistemic community framework. An epistemic community is “a network of professionals with recognized expertise and competence in a particular domain and an authoritative claim to policy relevant knowledge within that domain or issue-area”.17 The information and knowledge possessed by an epistemic community is considered an important dimension of power,18 and conferences can be purposefully examined as arenas for such influence to unfold. Specifically, experts play a central role in articulating cause-and-effect relationships in complex problems, shedding light on issue linkages, framing the collective debate, identifying the interests of a state, and helping formulate policies.19

Forces of globalization have made the nature of issues increasingly complex, which has led policy makers to turn to epistemic communities for advice.20,21 An epistemic community can influence knowledge production by framing the agenda, privileging certain types of knowledge, and by guiding the application of knowledge to specific policy concerns.22 These forces and trends are also at play in the Arctic region, and this article examines how conferences can be arenas for an epistemic community in the Arctic to frame the debate, contribute to agenda setting, and bring science into the policy-making process. Moreover, the promotion of open discussions in Arctic affairs must be seen in relation to the dynamics of Arctic governance, which has developed to include a variety of different Arctic and non-Arctic stakeholders. This article sheds light on the functions of conferences in this regard, as arenas for the inclusion of a broad variety of international participants from various affiliations in the dialogue about the future of the region.

2.3 Methods

The data collection process for this article has been two-fold, attending to both a quantitative mapping of Arctic conferences, including a more qualitative look at the Arctic Frontiers and Arctic Circle Assembly, and a comparison of what takes place in Arctic policy and central topics in these arenas. For the mapping of the Arctic conference sphere, I started by browsing online calendars of events, including the Arctic Research Consortium of the United States (ARCUS),23 the Arctic Portal,24 and websites of Arctic institutions, institutes, and journals.25 I then constructed an extensive database of conferences on Arctic issues,26 with particular focus on information about the organizers, participants, purpose, agenda, and central developments of the conferences. This information was obtained from the conferences’ websites and online programs and supplemented by other sources such as news articles, newsletters, blogs, and commentaries when appropriate.

Concerning the analysis of the Arctic Frontiers and Arctic Circle conferences, the thematic emphasis of held since their inception, 2007 and 2013 respectively, was obtained from previous programs.27 Arctic Frontiers has a set theme for each year, decided by the organizers, while the agenda of the Arctic Circle is decided primarily by participants who submit proposals for sessions. The review of past conference programs revealed four categories of topics that were given particular attention: the impacts of climate change and the environment; resource development and management; Northern communities and indigenous peoples; and maritime issues and the Arctic Ocean. These categories correspond with the emphasis of Arctic state policies and strategies.28

Having accounted for the theoretical framework and data collection process that supports this article, subsequent sections will account for the evolution of the Arctic conference sphere. Following this review, I will discuss the development of “hybrid” conferences in the Arctic, before I conclude with a discussion on how developments in the Arctic have opened for conferences to expand, and how conferences have contributed as links within the Arctic regime complex.

3 Conferences established from the 1960s to the 1990s

At the beginning of the twentieth century, the (Arctic) conference sphere was dominated by science-oriented arenas. One of the first Arctic conferences was the North Calotte Peace Days,29 a cultural meeting that ran from 1964 until the early 2000s. This conference connected civil societies and NGOs of the northernmost parts of Norway, Sweden, Finland, and the Soviet Union.30 Another similar conference, which emerged in 1989 was the Circumpolar Universities Cooperation Conference,31 which sought to encourage cooperation among Northern communities. Examples of larger international science union meetings that also have developed to address Arctic related issues include the International Council for the Exploration of the Sea Annual Science Conference (which originated in 1902), the American Association of Geography Annual Meeting (1904), the American Geophysical Union Fall Meeting (1920), the Society of Exploration Geophysicists Annual Meeting (1930), and the Western Regional Science Association Annual Meeting (1962).

The European Geoscience Union Annual Meeting has been organized since 1973, and covers topics such as climate, energy, and resources. It attracted 15,000 participants from more than 100 countries in 2018, and is the largest European geoscience event. The American Geophysical Union Fall Meeting is the largest earth and space science meeting in the world and was attended by approximately 24,000 participants in 2017. Such conferences with 10–20,000 participants do not produce a common statement or result in joint efforts. Instead, it is up to the participants to connect and initiate activities amongst themselves, which illustrates the central function that conferences have as meeting places and arenas for side-events.32 The ocean has been one of the dominant issues in the Arctic conference sphere since the 1970s. This can be seen in relation to the negotiation of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) from 1973 to 1982, when states worked to establish their rights and responsibilities through a framework to govern the world’s oceans.

| The International Conference on Port and Ocean Engineering under Arctic Conditions | Established: 1971

Arranged biannually Location: Rotating |

| The International Conference and Exhibition on Performance of Ships and Structures in Ice | Established: 1975

Arranged in 1981, 1984, 1990, 1994, 2000, 2006, 2008, 2010, 2012 and 2014 Location: Rotating |

| The Northern Research Basins Symposium and Workshops | Established: 1975

Arranged biannually Location: Rotating |

| The Arctic and Marine Oil-spill Program Technical Seminar on Environmental Contamination and Response | Established: 1978

Arranged annually Location: Canada |

| The Lowell Wakefield Fisheries Symposium | Established: 1982

Arranged semi-annually Location: Alaska |

| The International Conference of Ocean, Offshore and Arctic Engineering | Established: 1982

Arranged annually Location: United States |

| The Conference on Polar Meteorology and Oceanography | Established: 1983

Arranged biannually since 1999 Location: United States |

| The International Symposium on Cold Region Development | Established: 1983

Arranged every three years Location: Rotating |

3.1 Conferences in the 1990s

Conferences established in the 1970s and 1980s aimed to gather and engage scientists, experts, and specialists, but made no explicit mention of involving or communicating to policy-makers or the industry. We can note a somewhat broader agenda that also emphasizes collaboration among participants from different sectors at conferences established in the 1990s. The geopolitical landscape changed, and political leaders and heads of states and governments turned their attention to cooperative forums as the Cold War was ending. In 1991, the first ministerial meeting of the Arctic states was held in Finland, commencing the Rovaniemi process.33 Among the science forums that emerged at that time were the International Conference on Environmental Radioactivity in the Arctic, attending to nuclear safety in the Arctic, and the Calotte Academy, which was established in 1991 as a symposium intended to promote interdisciplinary, academic, and policy-oriented dialogue between actors from both academia and policy.34 Moreover, some of today’s main science conferences on Arctic issues emerged during the 1990s, such as the International Congress of Arctic Social Sciences (ICASS). ICASS has been arranged every three years since 1992, rotating with the International Arctic Social Science Association (IASSA) secretariat.

The IASSA exemplifies collaboration initiated in the Arctic after the end of the Cold War,35 founded on a suggestion made at the Conference on Coordination of Research in the Arctic held in Leningrad in 1988. The objectives of the IASSA are to promote and stimulate international cooperation, increasing the participation of social sciences in Arctic research, and to communicate and coordinate with other research organizations. ICASS gathers international researchers to share ideas about social science research in the Arctic. It is attended by Indigenous peoples, northerners, decision makers, politicians, and academics. In 2017, the University of Northern Iowa took over the IASSA secretariat, while the 2021 ICASS is scheduled to be held at the Northern Arctic Federal University in Russia. This demonstrates the collaborative efforts in the region, also promoted through conferences, and how science cooperation in the Arctic can be held separate from political tensions internationally.36,37

The International Conference on Arctic Research Planning (ICARP) is another science conference series initiated as the Arctic opened for more cooperation. It was established in 1995, and arranged again in 2005 and 2015. The ICARP is hosted by the International Arctic Science Committee (IASC) in cooperation with its partners. Its stated objective is to provide a forward-looking conference that focuses on international and interdisciplinary perspectives for advancing Arctic research cooperation and applications of Arctic knowledge. The third ICARP in 2015 was held based on the realization that, with increased scientific, political, and economic interest in the Arctic, there was need for better coordination and agreement around shared objectives across the Arctic states, and with other countries and international programs.

The Arctic Science Summit Week (ASSW) was initiated by the International Arctic Science Committee (IASC) in 1999 and is held annually at rotating locations. The purpose of the ASSW is to provide opportunities for coordination, cooperation, and collaboration among the various scientific organizations involved in Arctic research. In odd-numbered years, the ASSW includes a three-day science symposium, aiming to create a platform for exchanging knowledge, initiate collaboration, and attract scientists, students, policy makers, and professionals. In even-numbered years, the ASSW encompasses the Arctic Observing Summit (AOS), with the objective of providing community driven and science-based guidance for the design, implementation, coordination, and long-term operation of Arctic observing systems.

The Northern Research Forum (NRF) Open Assembly is another significant conference in terms of bringing research into the policy making process. The idea for the NRF was launched in 1998 by then-president of Iceland, Ólafur Ragnar Grímsson, and first held in Akureyri in 2000. The NRF Open Assembly was arranged biannually at various locations until 2015. The philosophy behind the NRF Open Assembly was founded in recognition of the need for open discussion and dialogue based on expertise. Its aim was to preserve the Arctic as a politically stable region, despite the environmental, economic, and geopolitical changes drawing global attention towards the region. The objective was to provide an opportunity for all stakeholders to take part in discussions on issues relevant for the Arctic region.

The review thus far demonstrates progress in the conference sphere, with more diversified stakeholder involvement and broader agendas. The emphasis on facilitating interdisciplinary forums is more noticeable, as are the stated purposes of involving and interacting with industry, engaging the political realm, and having an impact on political processes. As such, conferences are beginning to carve out their space within the Arctic regime complex, as purposeful links among other entities.

4 Conferences established 2000–2009

The Arctic Ocean, shipping, marine, and maritime topics further dominated conferences established in the early 2000s. In addition, climate change and energy-related issues were added to the agenda. In 2001, the Institute of the North initiated the Alaska Dialogue, and the Symposium on the Impacts of an Ice-Diminishing Arctic on Naval and Maritime Operations was established by the US National Ice Centre and the US Arctic Research Commission (USARC). Both the Institute of the North and USARC are examples of entities turning to conferences as tools for raising awareness and facilitating cooperation. Moreover, the Canadian Institute Energy Group’s Arctic Oil and Gas Symposium emerged in 2001 and has developed into North America’s primary Arctic oil and gas conference. The AECO Arctic Cruise Conference has been arranged annually in Oslo, Norway since 2003, and Alaska’s premier marine research conference, the Alaska Marine Science Symposium, has been held since 2004.

In 2005, there was a noteworthy peak in the establishment of conferences addressing Arctic issues. This corresponds with what Young called a “second state change” in Arctic affairs, brought about by developments that opened the Arctic to global concerns: the impacts of climate change and the spread of the socio-economic effects of globalization to the Arctic.38 Young considers the 2004 Arctic Climate Impact Assessment39 a symbol of this change, as it was the first Arctic Council assessment to comprehensively include the social sciences as well as the natural sciences in its assessment of the impacts of climate change on socio-economic conditions in the Arctic. Accordingly, the noted shift in the conference sphere in the 1990s, towards a more interdisciplinary approach, is also found in cooperative organizations.

The Arctic Net Annual Scientific Meeting, the largest annual Arctic research gathering in Canada, was one of the conferences emerging in 2005. Its stated aim is to be an arena for actors from all fields of Arctic research to highlight their work, stimulate networking and partnership activities, and address the global challenges and opportunities arising from climate change and modernization in the Arctic.40 The Polar Technology Conference was also arranged for the first time in the United States in 2005. It aims to bring together polar scientists and technology developers to exchange information on research system operational needs and technology solutions that have been successful in polar environments. Another conference originating in 2005 was the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) Arctic Division Annual Meeting, held in Alaska until 2014. The AAAS is the world’s largest general scientific society. The mission of its Arctic Division is to advance science and innovation, and enable people to respond and adapt to changes.

The High North Dialogue was established in 2006, and is arranged annually at the High North Center for Business and Governance at Nord University Business School, in Bodø, Norway. It gathers around 250–300 academics, postgraduates, policy makers, politicians, and businesses representatives to deliberate on various dimensions of Arctic change. The High North Dialogue, the Kirkenes Conference, and the Arctic Frontiers constitute the three main conferences on Arctic issues in Norway. The first Arctic Energy Summit took place in Fairbanks, Alaska in 2007, and has since been arranged in 2013 in Iceland, in 2015 in Alaska, and in 2017 in Finland. It was convened by the Institute of the North, sponsored by the US Department of State during the International Polar Year (IPY), and endorsed by the Sustainable Development Working Group of the Arctic Council. This summit is another example of the function of conferences as meeting places and connections between entities working towards shared goals within Arctic governance.

The first Arctic Frontiers was held in Tromsø, Norway in 2007. It was an initiative of the research company Akvaplan Niva, with the main objective of providing a knowledge base for political decision-making and for community and business development. Its stated purpose is to function as an international arena on sustainable development in the Arctic, addressing the management of opportunities and challenges to achieve viable economic growth with societal and environmental sustainability. Despite being one of the more expensive Arctic events, participant numbers have grown from around 500 in 2007 to approximately 1500 in 2020. In addition to the five-day conference in January, the organizers have held Seminars Abroad at international locations since 2014. These are intended to promote Norwegian expertise internationally and to draw attention to Norwegian priorities in the High North.

| The Institute for Arctic Policy (IAP) Conference | Collaboration between Dartmouth College, University of Alaska Fairbanks, and University of the Arctic. IAP brings together representatives from governments, NGOs, Indigenous peoples, and scientists to discuss, identify, and prioritize issues and policy-related research and to help develop the agendas for governments to address pressing policy issues. Topics include climate change and security, the Arctic Marine Shipping Assessment, human security, and Arctic health. |

| The Polar Law Symposium | The symposium is arranged at various locations. Its purpose is to examine the implications of the challenges faced by the Polar Regions for international law and policy, and to make recommendations on appropriate actions by states, policy makers, and other international actors to respond to these challenges. |

| The Northern Oil and Gas Research Forum | The forum was established as a biannual meeting with representation from government, industry, academia, Indigenous groups, and Northerners from Canada and the United States. It was arranged between 2008 and 2014, focusing on technical, scientific, and engineering research to support management and regulatory processes related to oil and gas exploration and development in the North. |

| The Arctic Shipping Forum North America | This forum, established in Canada, is the only event in North America dedicated to examining shipping operations in the Arctic and providing essential information for understanding the challenges of shipping operations in the Arctic. |

| The ACI’s Arctic Shipping Summit | The ACI Arctic Shipping Summit was established in Montreal, Canada to address topics related to Arctic shipping, such as regulations and requirements from the Polar Code and the Coast Guard. It brings together key industry stakeholders, including ship-owners, managers, solution providers, consultants, and technology providers. |

| The International Polar Tourism Network | Arranged biannually at rotating locations. Membership includes university researchers, consultants, tourism operators, government organizations, community members, and graduate students. The stated objectives are to generate, share and disseminate knowledge, resources, and perspectives on polar tourism, and to support the development of collaboration and cooperative relationships between members. |

| The Effects of Climate Change on the World’s Oceans International Symposium | Arranged for the first time in 2008 (Spain), and since in 2012 (South Korea), 2015 (Brazil) and 2018 (Washington DC). The stated objectives of the symposium are to bring together experts to better understand climate impacts on ocean ecosystems and how to respond by highlighting the latest information, identifying key knowledge gaps, promoting collaboration and stimulating the next generation of science and actions. |

| The International Arctic Change (Arctic Net) | Arranged in Quebec City, Canada, with a follow-up conference in 2017. It attracted around 1500 participants, including researchers, students, and decision-makers, and addressed the multiple challenges brought about by climate change and modernization of the Arctic. |

| The Kirkenes Conference

Norway |

The conference addresses policy, business, and community development in the High North. It is arranged annually and attracts around 300 participants, including Norwegian high-level delegates from several government ministries, regional and local politicians, Russian and EU delegates and representatives from research institutions and the industry. |

5 Conferences established 2010–2013

By the end of the 2000s, conferences emphasized the involvement of a broad range of entities in sharing information, making recommendations for actions, and developing cooperative relations and joint initiatives. As such, we can note a more proactive stance within the conference sphere. The turn of the decade brought with it another peak in the establishment of Arctic conferences, several of these in Russia. The International Arctic Forum (IAF) was inaugurated in 2010 (Moscow), and arranged in 2011 (Archangelsk), and in 2013 (Salekhard). This was Russia’s first high-level international platform for scientific discussions, expert exchange of opinions, and for providing recommendations on the Arctic intended to set the stage for further engagement in the region.41 In 2016, the Russian government decided that the conference was to become a biannual event, permanently hosted in Archangelsk in odd-numbered years. The conference is attended by representatives at the highest political level, including Russian President Vladimir Putin. The IAF is organized by the Roscongress Foundation, a socially oriented non-financial development institution, and in 2017 was arranged with the support of the State Commission for Arctic Development.

The IAF, together with the Arctic Circle Assembly and the Arctic Frontiers, are considered the “three major Arctic conferences”. In contrast to the others, a personal invitation is required to attend the IAF, and there is also a high registration fee (US$ 1833 in 2017). Nevertheless, the number of participants grew from 300 in 2010 to more than 2400 in 2017.42 The 2017 IAF brought together government bodies, international organizations, and scientific and business communities. The objectives of the conference are in line with Russia’s Arctic policy, with the aims of developing international cooperation, containing the Arctic as a zone of peace, consolidating efforts to ensure the sustainable development of the Arctic, and raising the standard of living for inhabitants of the Arctic.43

The Federal Arctic Forum: “Arctic Days” was established in 2010, aiming to draw attention to natural, historical, and cultural sites in the Arctic, increase the appeal of the Russian North as a tourist destination, and create dialogue on environmental problems in the Arctic. A third Russian Arctic conference emerging at this time, was the International Forum – “Arctic the present and the future” – which was held in St. Petersburg from 2011 to 2016. Each year, the forum produced a resolution that contained policy recommendations regarding the socio-economic development of the Arctic zone of the Russian Federation.

The conferences presented thus far have primarily been organized by societies, associations, research institutions, science committees, and institutes, however, the Russian government is clearly involved in the design and administration of these conferences. Moreover, the stated objectives of these conferences are in line with Russia’s foreign policy objectives in the Arctic.44 Despite the inclusion of international cooperation, there is a noteworthy expression of strategical positioning in these conference objectives. President Putin has repeatedly indicated that he wants Russia to become internationally recognized as a global power, and that an active Arctic presence can help achieve this.45 Conferences as display windows for Russia’s activities and priorities can be a means to this end. Furthermore, the goal of the Arctic Days, which emphasizes Russian Arctic exceptionalism, is in line with how Russian leaders use references to historical and cultural presence in the region as an identity-building mechanism to justify proactive (often resource-demanding) Arctic policies.46 Accordingly, the utilization of the above-mentioned arenas by the Russian government can be considered a means for the powerful state to assert its dominance, control the agenda, and catalyze outcomes to its benefit.

In 2010, the Arctic Futures Symposium, initiated and arranged by the International Polar Foundation, was established in Brussels, Belgium. The stated aim of the forum is to raise public awareness of important developments in the Arctic region. The Sustainable Ocean Summit (SOS) was also arranged for the first time in 2010, in Belfast, Ireland, organized by the World Ocean Council. It was designed to attract leading companies to addresses priorities for cross-sectoral industry leadership, and collaboration in ocean sustainability. Lastly, the Consortium for Ocean Leadership has held a Public Policy Forum in Washington DC since 2010. This is a day-long public meeting that facilitates ocean policy discussions with representatives from the US Congress, federal agencies, industry, and the academic research community.

Since 2011, the North Pacific Arctic Conference on Arctic Futures (NPAC) – a joint venture between the East-West Center and the Korea Maritime Institute (KMI) – has been held annually at the East-West Center in Hawaii. While NPAC is for invited participants only, the papers presented at the conference are published in a series of proceedings entitled The Arctic in World Affairs. Participants represent the Arctic states of the North Pacific region (Canada, Russia, and the USA) and non-Arctic states (China, Japan, and the Republic of Korea). The Arctic Security Forces Roundtable (ASFR) is another conference held annually since 2011. It was established at the initiative of the US European Command and the Norwegian Defense Staff and designed to promote regional understanding, and enhance multilateral security operations within the Arctic area. The ASFR is also a closed meeting of senior military and coast guard leaders from states that have coastlines above the Arctic Circle or a significant interest in the Arctic.

In 2012, the Fletcher Arctic Conference was established at Tufts University in Massachusetts. It has since been arranged annually, with the aims of creating conversation and constructive debate between speakers and participants, and providing a forum to address the implications of an opening Arctic. The Economist: The World Ocean Summit was also held for the first time in 2012, and has been arranged in Singapore, the US, Portugal, Bali, and Mexico. The Summit focuses on challenges and possibilities related to the oceans, sustainable management, and the transition to a new blue economy, and the involvement of capital and the private sector. In 2013, the Arctic Observing Summit (AOS) originated in Vancouver, Canada. It has since been arranged in 2014 (Helsinki, Finland), 2016 (Fairbanks, Alaska), and 2018 (Davos, Switzerland). The stated objective is to provide community-driven, science-based guidance for the design, implementation, coordination, and sustained long-term operation of an international network of Arctic observing systems. Another internationally rotating conference emerging in 2013 was the International Conference of the IASC thematic network, aiming to develop an understanding of Arctic environmental change.

The Arctic Encounter Symposium (AES), established in 2013, is the largest annual conference on Arctic policy, security, and economics convening in the United States. The long-term strategy of the organizers is to provide an educational platform for raising awareness and drawing attention towards Arctic issues within the US government, among business leaders, and civil society. Thus, the organizers aim to be useful for new stakeholders, providing an arena where they can learn “Arctic 101”, network, and establish a connection to the region. At the same time, the organizers want the conference to be attractive for experts, as a forum where they can obtain new information, and further develop their connections. Moreover, an essential driver for the organizers is to connect back to people and local communities. The conference has a variety of partners, many of which are from Alaska.

The Promise of the Arctic was held in Seattle, Washington in 2013, 2015, and 2016. It is a production of Philips Publishing Group, in cooperation with the Institute of the North, and the Alaska Division of Economic Development. The conference focuses on emerging economic opportunities in the Arctic, and was developed to help those involved in maritime transportation, construction, or resource extraction to maximize the economic potential of the Arctic. The conference also addresses environmental best practices developed to protect the Arctic waters, and how to respond to the economic and cultural needs of native populations.

The Arctic Circle Assembly was held for the first time in Reykjavik, Iceland in 2013, aiming to be a global platform that brings together all Arctic and non-Arctic stakeholders interested in the development of the region and its significance for the future. By 2019 the Arctic Circle was the largest network of international dialogue and cooperation on the future of the Arctic, and attended by participants from a wide variety of sectors and nationalities. In addition to the main Assembly, the Arctic Circle has arranged Forums at various international locations since 2015. Other conferences emerging in the Nordic countries in 2013 were the Rovaniemi Arctic Spirit, the Arctic Patrol and Reconnaissance Conference in Copenhagen, Denmark and the Arctic Exchange in Stockholm, Sweden.

There are two elements are worth noting regarding developments between 2010 and 2013. Firstly, the business/industry component is becoming remarkably stronger. The concept of sustainability is coupled with economic opportunities and environmental protection. It is increasingly recognized that to manage the growing interests in the region, while preserving and advancing healthy communities, industry actors must be involved and engaged in this mission. This leads to the second element worthy of attention: the explicit involvement of Arctic local communities. This is detectable when reviewing the stated purposes, topics, and associated partners of the emerging arenas.

6 Conferences established 2014–2020

The business element continued to prevail at Arctic conferences in the second half of the decade. In 2014, the Arctic Business Conference was arranged in Bodø, Norway as part of the Arctic Business initiative, launched in 2013 as a partnership between the Norwegian Shipowners’ Association, DNV GL, Kongsberg, and Equinor. The Arctic Institute, established in 2011 as a non-profit organization in Washington DC with a network of researchers across the world, partnered with the Arctic Business initiative to boost their communication with business leaders from the Arctic. This collaboration is an example of synergies between research and business created through conferences.

The American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) Center for Science Diplomacy has arranged the Science Diplomacy Conference in Washington DC since 2015. This conference brings scientists, policymakers, practitioners, and students together around emerging aspects of science diplomacy. Key points emerging from the 2017 conference were the interests of the emerging “near-Arctic states” in investing in the region, how science diplomacy fits within the complex system of international relations in the Arctic, and that existing partnerships and collaborations provide opportunities for continued scientific cooperation.

The UArctic Congress was arranged in St. Petersburg, Russia in 2016 by the University of the Arctic (UArctic) and St. Petersburg University. The conference, entitled The sustainable future of the Arctic, was attended by 450 participants, representing 200 institutions from 20 countries. In 2017, the World Climate Research Program and the Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission of UNESCO organized an international conference on sea level research, addressing the existing challenges in describing and predicting regional sea level changes, and in quantifying intrinsic uncertainties. The conference followed eleven years after the first WCRP sea level conference (hosted in Paris in 2006), and three years after the last Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

7 The need for hybrid conferences

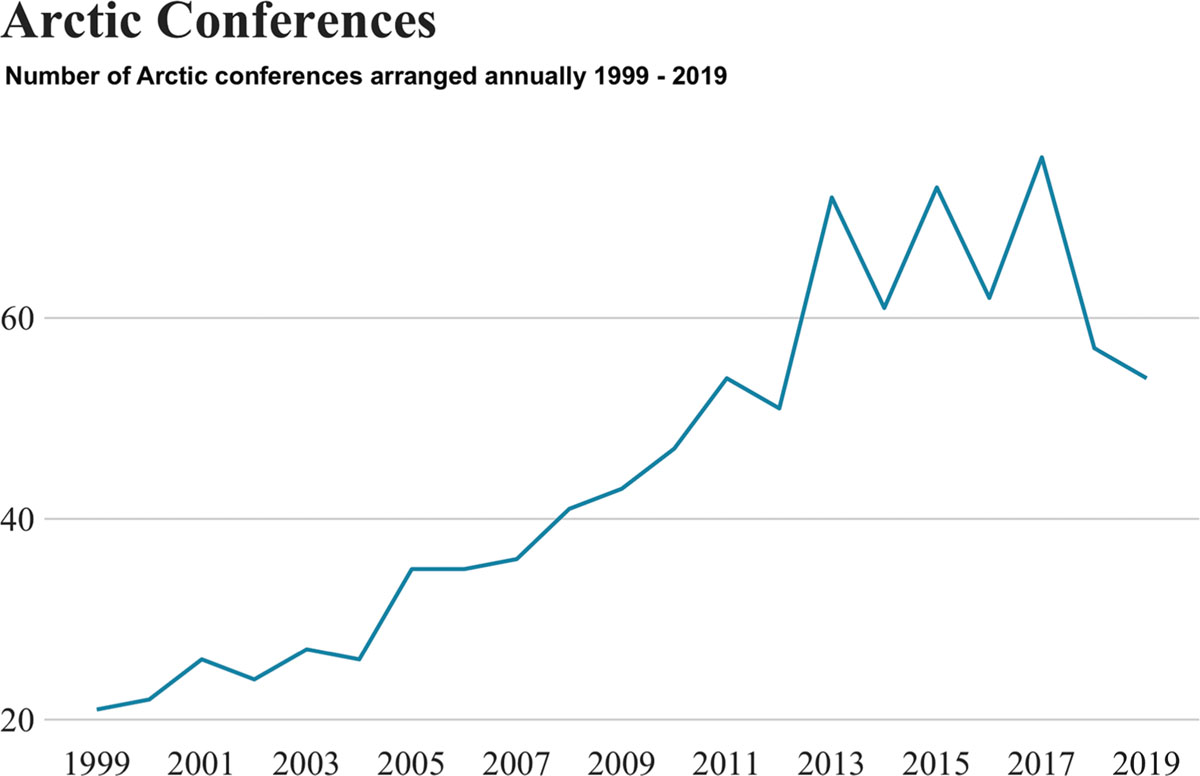

There has been an extensive growth in the number of conferences attending to Arctic issues since the beginning of the twenty first century (see Figure 1). This can be seen as a result of both Arctic issues assuming a global dimension, and the fact that a growing number of non-Arctic state actors have developed an interest in participating in economic and political developments in the region.47 Considering that the observers have a limited role in discussions, and no say in the decision-making of the Arctic Council, this spurred the need for additional arenas to incorporate all voices and issues within Arctic governance.48 Thus, the trend towards more open discussions, also through conferences, can be seen as related to the dynamics of Arctic governance. Still, many Arctic conferences hosted in non-Arctic states are not necessarily in tune with the realities of Arctic living conditions, and open arenas imply a promotion of the perspectives of non-Arctic state actors, which can be disconnected from the interests of Arctic rights-holders.49 Therefore, quantity in numbers must not be confused with quality in content. At the same time, with more arenas for discussions on Arctic affairs, the epistemic community is provided with additional “testing grounds” to generate and launch new ideas and proposals.50 This can contribute to driving the dialogue forward. The involvement of more stakeholders in this process through conferences is a constructive contribution to the Arctic governance regime complex.

Proceeding from this argument, I now consider the significance of conferences within Arctic affairs from the mid-2000s, focusing specifically on the two largest international gatherings in the region: Arctic Frontiers and Arctic Circle Assembly. This section also identifies elements that contributed to opening a window of opportunity for this hybrid conference form around 2007. Through examining topics addressed at these conferences connected to developments within Arctic policy, science, and business, the following section sheds light on the functions of conferences within the Arctic governance regime complex, adding to the workings of the Arctic Council and other entities operating in the region. As mentioned above, the main ambition of the organizers of Arctic Frontiers was to construct an arena for bringing science into the policy-making process. The main objective of Arctic Circle Assembly was to provide an arena for open dialogue among a variety of stakeholders, including non-Arctic state actors. Thus, we can see how the two conferences were designed to fill different spaces within the Arctic governance system.51

| Year | Arctic Policy | Arctic Frontiers |

|---|---|---|

| 2006 | The Norwegian Government’s High North Strategy was issued as the first Arctic policy. | The AF was initiated to provide for knowledge-based decision-making, and social, economic, and business development. |

| 2007 | Planting of the Russian flag on the seabed of the North Pole.

Norway assumed the Arctic Council chairmanship. Focus areas: sustainable resource management, efforts to combat climate change. The International Polar Year (2007–2009). The Arctic Council issues the Assessment of Oil and Gas Activities in the Arctic. |

“The Unlimited Arctic”

The policy part is promoted as a policy-making conference, while the science section is highly technical – resembling a “traditional” science conference. |

| 2008 | The Arctic Five signed the Ilulissat Declaration, committing to the legal framework provided by the Law of the Sea in the mapping of continental shelves.

The European Union and the Arctic Region was issued by the European Commission. |

“Out of the Blue”

Addressing challenges for oil and gas development in the Arctic. Norway’s interest represented by both by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Statoil. AMAP had three presentations with conclusions from the Arctic Oil and Gas Assessment. |

The year 2007, when the Arctic Frontiers first was arranged, is considered a threshold in Arctic affairs.52 In August 2007, a Russian science expedition sent two mini submarines down to the underwater Lomonosov Ridge, which Russia claims is directly connected to its continental shelf, and planted a Russian flag there.53 The move was described as “an openly choreographed publicity stunt”, and “a symbolic move to enhance the government’s disputed claim to nearly half of the floor of the Arctic Ocean and potential oil or other resources there”.54 The event was interpreted as a direct claim to the North Pole,55 and caused an observable change in the discourse about the Arctic, putting sovereignty issues on the agenda.56 This issue must also be seen in light of the ongoing processes by the Arctic states to map out their extended continental shelves, wherein they can exercise sovereign rights over the resources of the seabed and subsoil. When the Russian flag planting occurred, Canadian Minister of Foreign Affairs Peter MacKay stated: “This isn’t the 15th century. You can’t go around the world and just plant flags and say we’re claiming this territory”.57 Russia’s actions sparked discussions about the future of Arctic governance,58 intensified diplomatic efforts (such as the Ilulissat Declaration), and renewed attention to national military capacity in the region.59,60

With changes in the political climate came changes in the Arctic conference sphere, and conferences increasingly became arenas aimed at bringing science into the policy and decision-making processes. Conferences also became more interdisciplinary, as different issue areas became increasingly interlinked, and cross-sectoral, as the need for information exchange and communication among various stakeholders became more pressing. Accordingly, Arctic Frontiers and Arctic Circle Assembly can be considered a hybrid form of conferences, somewhat distinct from their predecessors. By bringing stakeholder groups together, and fostering inter-disciplinary and cross-sectoral dialogue on the Arctic, they have greater potential to contribute to the science, policy, business interplay.

The initiative of Arctic Frontiers to provide for knowledge-based decision-making in 2007 was timely, considering the increased interest in the region, and the need for balancing economic development with environmental concerns. This also coincided with the focus of the joint Norwegian-Swedish-Danish umbrella program for their successive Arctic Council chairmanships, as well as the International Polar Year (IPY) research program. Central topics at Arctic Frontiers were opportunities and challenges resulting from climate change, the development of sustainable communities, the Arctic Ocean, social and economic issues, and the human dimension. Energy is also a recurring issue in the Arctic Frontiers’ programs, and was the overarching theme for the 2012 conference, which was attended by the Norwegian Minister for Petroleum and Energy, Aker Solutions, Conoco Phillips, and other international industry representatives. This illustrates a key characteristic of Arctic Frontiers: how it serves as a channel to promote the Norwegian government’s interests and priorities.61

| Year | Arctic Policy | Arctic Frontiers |

|---|---|---|

| 2009 | Arctic policy documents issued:

Denmark assumed the Arctic Council chairmanship. Focus areas: Peoples of the Arctic, IPY legacy, climate change, biodiversity, megatrends in the Arctic, integrated resource management, operational cooperation, the AC in a new geopolitical framework. |

“The Age of the Arctic”

Two main themes: New opportunities and challenges resulting from climate change; Management of the Arctic Seas. Included a separate section on results from the International Polar Year. |

| 2010 | Arctic policy document issued:

Russian-Norwegian Treaty Maritime Delimitation and Cooperation in the Barents Sea and the Arctic Ocean |

“Living in the High North”

Main emphasis on changes in strategies for the Arctic and sustainable communities. |

| 2011 | Arctic policy documents issued:

Sweden assumed the Arctic Council chairmanship. Focus areas: The environment, climate change, people, and the ocean

|

“Arctic Tipping Points”

Addressing sea ice and oceanographic perspectives, marine ecosystems and fisheries, socio-economic and institutional perspectives, and people of the North. Attended by large number of ministers, ambassadors, governors, and business representatives. |

| 2012 | The European Commission issues Developing a European Union Policy towards the Arctic Region: progress since 2008 and next steps. | “Energies of the High North”

Thematically, a shift from primarily emphasizing climate change and the human dimension, towards focusing on energy resources, industrial development, and the development of secure and sustainable energy projects. |

All of the Arctic states had issued a strategy for the region by 2011, and the Arctic Council established its permanent secretariat in Tromsø, which was operational from 2013. That year is a central one when examining conferences in relation to political developments. There were six pending observer states, including China, prior to the Arctic Council ministerial meeting in Kiruna in May 2013. The Arctic states were concerned that if the Arctic Council did not accept these states as observers, they would create an Arctic forum of their own. In his opening speech at the Arctic Frontiers in January 2013, then Foreign Minister of Norway, Espen Barth Eide, stated: “We are happy that more people want to join our club, because this means that they are not starting another club, and that gives us some influence on what topics are discussed in relation to the Arctic”.62

The growing interest among Asian states to participate in Arctic affairs63 was also part of the reason for the skepticism towards the launch of the Arctic Circle Assembly at the National Press Club in April 2013. The initiator, Icelandic president Olafur Ragnar Grímsson, described the Assembly as “an open tent involving all interested stakeholders”,64 and some Arctic state actors perceived this as an intended alternative, or even a threat, to the Arctic Council.65 Thus, the announcement of the Arctic Circle thus added to the discussion among the Arctic Council’s members, regarding whether to accept the Asian states as observers. It also contributed to the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs becoming more involved in the organization of the Arctic Frontiers.

| Year | Arctic Policy | Arctic Frontiers | Arctic Circle |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2013 | Arctic policy documents issued:

|

“Geopolitics and Marine Production in a Changing Arctic”

Business forum arranged for the first time: Business development in Norwegian fisheries and aquaculture. |

The Arctic Circle Assembly launched in April as an open tent for all stakeholders to participate in the dialogue on the future development of the region and its consequences for the globe. |

| Canada assumes Arctic Council chairmanship.

Development for the people of the North – focusing on responsible Arctic resource development, safe Arctic shipping, and sustainable Arctic communities Arctic Council secretariat became operational in Tromsø. Arctic Council Ministerial Meeting in Kiruna in May. Accepted new observers: China, Japan, South-Korea, Singapore, India, and Italy. Agreement on Cooperation on Marine Oil Pollution in the Arctic. |

The ACA was met with skepticism from the Arctic states due to the involvement of non-Arctic state actors.

The ACA in October was attended by 1200 participants. |

The 2013 Arctic Frontiers included a ministerial session, attended by the Foreign Ministers of Norway and Sweden, the Minister of Health of Canada, and the EU Commissioner for Maritime Affairs and Fisheries. It was also attended by ambassadors to Norway from China and South Korea, and governors from Russia and Alaska. The closer involvement of the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in organizing Arctic Frontiers is visible in the 2015 program, and by the attendance by high-level delegates. The business element became more prominent in the conference sphere, and Arctic Frontiers added a business pillar to its format in 2014. The 2015 Arctic Frontiers conference titled Climate and Energy particularly reflected the industry dimension, with speakers from Conoco Philips, Statoil, the Chinese National Petroleum Corporation, and the Russian Geographical Society.

| Year | Arctic Policy | Arctic Frontiers | Arctic Circle |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2014 | Arctic policy document issued:

The Arctic Economic

|

“Humans in the Arctic”

Health, environment and society and maritime operational challenges. Coincided with Canadian AC chairmanship program. Business Forum North Seminars Abroad arranged for the first time. |

1400 participants

Opening speeches by the prime minister of Iceland, the president of Finland, and the chancellor of Germany. Country sessions by Finland, the UK, Japan, and France. |

| 2015 | The United States assumes Arctic Council chairmanship:

One Arctic with Shared Opportunities, Challenges and Responsibilities Focus areas: Improving Arctic Ocean governance, climate change, improving economic and living conditions for Arctic residents Arctic Coast Guard Forum was established. UN Framework Convention on Climate Change COP-21 UN Sustainable Development Goals (adopted) |

“Climate and Energy”

Timely topics related to the international COP-21 focus. Three main themes: Arctic climate change – global implications; ecological winners and losers in future Arctic marine ecosystems; and the Arctic’s role in the global energy supply and security. The Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs became involved in arranging Seminars Abroad. |

1500 participants

Keynote by President of France, François Hollande: The importance of the Arctic as an arena for international climate action, leading up to COP-21. The Arctic Economic Council presented. Pronounced presence of non-Arctic states: Country sessions by China, Germany, and Japan. The EU presented its Arctic policy, and a Korean Night was hosted. Arctic Circle Forums Anchorage, Alaska (August) and Singapore (November) |

The international outreach of the conferences was strengthened with the establishment of the Arctic Frontiers’ Seminars Abroad (2014) and the Arctic Circle Forums (2015). The global relevance was further reflected in how climate issues rose on the agenda pending the COP-21 conference in Paris in December of 2015, both at Arctic Frontiers, with a session called Towards COP21, and at the Arctic Circle with a keynote by President Hollande of France. Accordingly, by the mid-2010s, Arctic Frontiers and the Arctic Circle had become an arm of international diplomacy for the Norwegian and Icelandic ministries of foreign affairs.

Considering the two conferences as elements among other units in the Arctic regime complex, their relationship to the Arctic Council is a central distinction. The organizers of Arctic Frontiers consider the conference to be more in accordance with the Arctic Council’s “way of thinking”, protecting the interests of the Arctic Eight, while the Arctic Circle is more open to the interests and perspectives of non-Arctic states.66 Thus, through the primacy given to Arctic state speakers, the Arctic Frontiers mirrors the Arctic Council’s structure of “members” and “observers”. This connection is evident through the themes of the Arctic Council chairmanships and titles of the Arctic Frontiers. The Canadian chairmanship (2013–2015) – Developments for the people of the North – coincided with the Humans in the Arctic 2014 Arctic Frontiers, the 2017 Arctic Frontiers White Space – Blue Future was concurrent with the United States’ (2015–2017) emphasis on Arctic Ocean governance, and the Finnish (2017–2019) chairmanship’s focus on connectivity was reflected in the 2018 Arctic Frontiers Connecting the Arctic.

| Year | Arctic Policy | Arctic Frontiers | Arctic Circle |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | Arctic Council 20-year anniversary

An integrated European Union policy for the Arctic issued by the European Commission. |

“Industry and Environment”

Policy sessions addressed the state of the Arctic, science and technology for the future, and industry and environment. The format of breakout sessions and armchair talks continued. Topics were the Arctic Council’s 20th anniversary, oil spill prevention and SAR, COP21 revisited, the Arctic Economic Council, and the future of Arctic Marine Cooperation. |

2000-plus participants

Keynote by Nicola Surgeon, first minister of Scotland. Country presentation by Switzerland (pending Arctic Council Observer May 2017). Dominant issues: economic growth, tourism, shipping, international cooperation on safety, security, and emergency preparedness. Arctic Circle Forums Nuuk, Greenland (May) Quebec City, Canada (December) |

| 2017 | Arctic policy document issued:

Finland assumes Arctic Council chairmanship.

|

“White Space – Blue Future”

Focus on knowledge gaps about the oceans and the role they will play in the future. Attended by several high-level delegates – the prime ministers of Norway and Finland; foreign ministers of Sweden, Iceland, and Hungary; and ministers from Denmark and Russia. The industry and NGOs working on the blue-green economy and energy is also strongly represented. |

2000-plus participants from 60-plus countries

The Munich Security Conference hosted an Arctic Security Roundtable. Himalaya as the Third Pole in focus. Country sessions by Finland (sharing of icebreakers), Denmark (science and research), United Arab Emirates (energy and climate), India, and Poland. Arctic Circle Forums Washington DC (June): The United States and Russia in the Arctic. Edinburgh, Scotland (December): Scotland and the New North |

In 2016, the Arctic Council celebrated its twentieth anniversary, which sparked discussions about its functions, successes, and weaknesses within the Arctic governance structure. The EU issued a new Arctic policy, and following the United Kingdom’s decision to leave the EU in June 2016, Scotland’s First Minister Nicola Sturgeon held a keynote at the Arctic Circle Assembly in October. In her speech, Sturgeon expressed that Scotland did not support leaving the EU, and that Scotland was seeking partnerships and alliances in the North Atlantic, independent of the UK’s actions. The Scottish government further utilized the Arctic Circle organization for the purpose of promoting new collaborations, by hosting a Forum called Scotland and the New North in December 2017 that addressed areas of common interest between Scotland and the Arctic.67 The Scottish government’s utilization of both the Arctic Circle Assembly and the Forum for the purpose of assuming a new geopolitical position in Europe following Brexit illustrates not only the function of the conference arena for broader international processes, but also how conferences serve as stages for newcomers to promote themselves as stakeholders in the Arctic.

| Year | Arctic Policy | Arctic Frontiers | Arctic Circle |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 | Arctic Council Agreement on Enhancing International Arctic Scientific Cooperation (signed)

Agreement to Prevent Unregulated High Seas Fisheries in the Central Arctic Ocean (signed) White Paper on China’s Arctic Policy issued IPCC Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5°C |

“Connecting the Arctic”

Addressing the state of the Arctic, technology and connectivity, resilient Arctic societies and business development, healthy and productive oceans, industry, and environment. Topic coincided with the Finnish Arctic Council chairmanship’s priority. |

Arctic Circle Forums

Faroe Islands (May) Arctic Hubs: Building Dynamic Economies and Sustainable Communities in the North Seoul, South Korea (December) Asia Meets the Arctic: Science, Connectivity and Partnerships |

| 2019 | Arctic policies issued:

Iceland assumes Arctic Council chairmanship.

|

“Arctic Frontiers: Smart Arctic” Plenary program built around five main sessions: The state of the Arctic, blue growth, smart solutions, bridging the gap, and Arctic business prospects. | Arctic Circle Forums

Shanghai, China (May) China and the Arctic: Polar Silk Roads – Science and Innovation – Transport and Investment – Sustainable Development – Oceans – Energy – Governance |

Arctic Frontiers continued its thematic focus on the ocean, with an Arctic Frontiers Plus session on the Arctic Council’s work on the ocean in 2017, and also embraced the Blue-Green Economy trend within the international discourse.68 Through 2018 and 2019, Arctic Frontiers and Arctic Circle Assembly continued to address contemporary issues, reflecting broader developments within Arctic governance. The Arctic Frontiers thematic focus supports the Finnish Arctic Council chairmanship (2017–2019), emphasizing connectivity in 2018, and smart and resilient Arctic societies in 2019. Iceland took over the Arctic Council chairmanship in 2019, and Iceland’s Minister of Foreign Affairs was present at the Arctic Circle in both 2018 and 2019 to present Iceland’s visions and priorities.

The geopolitical importance of the Arctic became noticeably more significant around 2018, when China issued a white paper on its Arctic policy, describing itself as a “near-Arctic state” seeking to build a Polar Silk Road as part of the Belt and Road initiative.69 With China’s interest in investing in infrastructure and other projects in the region, particularly on Greenland, the United States became a more engaged Arctic actor.70 Relatedly, with the remilitarization of the Russian Arctic coast71 and growing interest of China, the European Union sought to expand its involvement in the region.72 The Arctic Circle has increasingly become an arena for geopolitical games to unfold, and through the organization, non-Arctic states are provided the opportunity to host Forums to promote their engagement in the Arctic.

9 Conclusions

This article has provided an historical overview of the evolution of the Arctic conference sphere and accounted for the significant number of interdisciplinary and cross-sectoral Arctic conferences. It has cast light on events in Arctic governance, and how conferences have developed along with central processes within Arctic affairs. During the Cold War, the conference sphere was characterized by science unions’ meetings, and events hosted by universities, research institutes, and NGOs. Dominant topics were the oceans, sustainable development and environmental protection, nuclear safety, security, and Indigenous peoples’ issues. Then, from the 1990s onwards, more attention was given to cooperation and collaboration through interdisciplinary, cross-sectoral, and multinational initiatives. Two factors contributed to this development. The first was the opening of relations between the East and the West following the end of the Cold War. The second was growing concern over pollution and nuclear safety in the Arctic, and the need for joint efforts to deal with such global challenges.

Accordingly, a window opened for Arctic issues to rise on the international agenda in the late 1980s and early 1990s, resulting in the initiative to establish the Arctic Council in 1996, as a means of promoting cooperation and coordination on issues such as sustainable development and environmental protection. However, this article has drawn attention to the fact that while the Arctic Council is a central hub in the Arctic governance regime complex, it is not sufficient to take into consideration all voices and interested stakeholders within Arctic affairs. The movement towards promoting open dialogue in the Arctic has been linked to the dynamics of Arctic governance, which has developed to include a diverse pool of Arctic and non-Arctic stakeholders with joint and diverging interests and priorities.

Consequently, a second window opened around 2007, for Arctic conferences to expand both in number and popularity. Sovereignty concerns became increasingly prominent, which was partly caused by the impacts of climate change and forces of globalization. This generated the need for additional arenas for actors engaged in Arctic affairs. The chronology has shown that there were peaks in the establishment of Arctic conferences in 2005 and between 2010 and 2013. The peak in 2005 was linked to Young’s “second state change” in Arctic affairs, also brought about by the impacts of climate change, and the spread of socio-economic effects from the globalization of the Arctic. The second peak is linked to the growing interest of non-Arctic states to engage in Arctic affairs, as well as how the Arctic is a core field of interest for the epistemic community. The latter is evident in the number of research funding programs, projects, and university courses devoted to Arctic issues.

From these developments within Arctic governance, Arctic Frontiers was established based on the need for arenas that brought scientific knowledge into the policy making process, and to secure knowledge-based business and community development. The launch of Arctic Circle Assembly in 2013 further attested to this connection between developments within Arctic governance and the conference sphere, as well as the developing interdisciplinary and inter-sectoral character of Arctic conferences. Arctic conferences have become central arenas for advancing the interplay between policy, science, and business, where the epistemic community plays a key role. Moreover, non-Arctic states are pushing for involvement in the region, and should be included in discussions so that their interests in economic development can be balanced against the interests of Arctic rights-holders. For these purposes, conferences have become central links among other entities within the Arctic regime complex. Conferences are arenas for agenda-setting, relationship-building, and networking, and marketplaces for the promotion of ideas. Conferences are also important magnets for a variety of side-events, meetings, and informal diplomatic endeavors, and thus contribute to connecting various actors engaged in Arctic affairs.

NOTES

- 1. Oran R. Young, “Governing the Arctic: From Cold War Theatre to Mosaic of Cooperation,” Global Governance 11 (2005): 9–15.

- 2. Duncan Depledge and Klaus Dodds. “Bazaar Governance: Situating the Arctic Circle,” In Governing Arctic Change: Global Perspectives, eds. Kathrin Keil and Sebastian Knecht (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017): 141–160.

- 3. Oran R. Young, “Arctic Politics in an Era of Global Change,” Brown Journal of World Affairs 19 (2012): 165–178.

- 4. Young, “Governing the Arctic”: 10.

- 5. Olav Schram Stokke, “Environmental Security in the Arctic: The case for multilevel governance,” International Journal 66 (2011): 835–848.

- 6. Elana Wilson Rowe, “Analyzing Frenemies: An Arctic Repertoire of Cooperation and Rivalry,” Political Geography, 76 (2019): 1–10.

- 7. Frank Biermann and Rakhyun E. Kim, “Architectures of Earth System Governance: Setting the Stage,” in Architectures of Earth System Governance. Institutional Complexity and Structural Transformation, eds. Frank Biermann and Rakhyun E. Kim (Cambridge University Press, 2020): 1–34.

- 8. Andrew Hurrell, “One World? Many Worlds? The Place of Regions in the Study of International Society,” International Affairs 83 (2007): 127–146.

- 9. Oran R. Young, “The Architecture of Global Environmental Governance: Bringing Science to Bear on Policy,” Global Environmental Politics 8 (2008): 14–30.

- 10. Frank Biermann, Earth System Governance: World Politics in the Anthropocene (MIT Press, 2014).

- 11. Frank Biermann and Rakhyun E. Kim. “Architectures of Earth System Governance: Setting the Stage,” in Architectures of Earth System Governance. Institutional Complexity and Structural Transformation, eds. Frank Biermann and Rakhyun E. Kim (Cambridge University Press, 2020): 1–34.

- 12. Biermann and Kim, “Architectures of Earth System Governance: Setting the Stage”, 7–9.

- 13. Amandine Orsini, Jean-Frédéric Morin and Oran R. Young, “Regime Complexes: A Buzz, a Boom, or a Boost for Global Governance?” Global Governance 19 (2013): 27–39.

- 14. Laura Gómez-Mera, Jean-Frédéric Morin and Thijs van de Graaf. “Regime Complexes,” in Architectures of Earth System Governance. Institutional Complexity and Structural Transformation, eds. Frank Biermann and Rakhyun E. Kim (Cambridge University Press, 2020): 137–157.

- 15. Ibid., 139.

- 16. Christopher R. Rossi, “The Club within the Club: The Challenge of a Soft Law Framework in a Global Arctic Context,” The Polar Journal 5 (2015): 8–34. DOI: 10.1080/2154896X.2015.1025490.

- 17. Peter Haas, “Epistemic communities and International Policy Coordination,” International Organization, 46 (1992): 1–35.

- 18. Ibid., 2.

- 19. Ibid., 15.

- 20. Ibid., 12–13.

- 21. See also Mai’aa K. Davis Cross, “Rethinking Epistemic Communities Twenty Years Later,” Review of International Studies 39 (2013): 137–160.

- 22. Oran R. Young, “Navigating the Interface,” in The Arctic in World Affairs. A North Pacific Dialogue on International Cooperation in a Changing Arctic, eds. Oran Young, Jong Deog Kim and Yoon Hyung Kim, (Seoul, Republic of Korea: Korea Maritime Institute Press, 2014): 225–250.

- 23. https://www.arcus.org/events/arctic-calendar

- 24. https://arcticportal.org/eventscal

- 25. I found great use of the Arctic Yearbook and its inventory of Arctic meetings, conferences, and events: https://arcticyearbook.com/arctic-yearbook/2013/2013-commentaries/54-a-proliferation-of-forums-a-second-wave-of-organizational-development-in-the-arctic

- 26. The full overview of these conferences can be acquired by contacting the author.

- 27. Past programs of the Arctic Frontiers are available here: https://www.arcticfrontiers.com/conference/ and past programs of the Arctic Circle Assembly are available here: http://www.arcticcircle.org/

- 28. Lassi Heininen, Karen Everett, Barbora Padrtová and Anni Reissell. Arctic Policies and Strategies – Analysis, Synthesis, and Trends. International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (2020).

- 29. Lassi Heininen and Chris Southcott, Globalization and the Circumpolar North (University of Alaska Press, 2010): 268.

- 30. The author wishes to thank one of the reviewers for pointing out some of the early conferences on Arctic issues, which had been overlooked in the initial mapping of the Arctic conference sphere.

- 31. UArctic. “CUA: Communication and Collaboration Between the Peripheral Areas of the North.” Accessed April 4, 2021. https://www.uarctic.org/shared-voices/shared-voices-magazine-2017/circumpolar-universities-association-communication-and-collaboration-between-the-peripheral-areas-of-the-north/

- 32. Eva Lövbrand, Mattias Hjerpe and Björn-Ola Linnér, “Making Climate Governance Global: How UN Climate Summitry Comes to Matter in a Complex Climate Regime,” Environmental Politics 26 (2017): 580–599.

- 33. Timo Koivurova, “Limits and possibilities of the Arctic Council in a rapidly changing scene of Arctic governance,” Polar Record 46 (2010): 146–156.

- 34. Calotte Academy. “About Calotte Academy.” Accessed April 7, 2021. https://calotte-academy.com

- 35. Oran R. Young, “The Arctic in Play: Governance in a Time of Rapid Change,” The International Journal of Marine and Coastal Law 24 (2009): 423–442.

- 36. Paul Arthur Berkman, “Stability and Peace in the Arctic Ocean through Science Diplomacy,” Science and Diplomacy (2014). http://www.sciencediplomacy.org/perspective/2014/stability-and-peace-in-arctic-ocean-through-science-diplomacy.

- 37. Michael Byers, “Crises and International Cooperation: An Arctic Case Study,” International Relations 31(2017): 1–28.

- 38. Young, “The Arctic in Play”: 427.

- 39. The assessment was produced by the Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme (AMAP) in collaboration with the Arctic Council’s Conservation of Arctic Flora and Fauna (CAFF) working group, and the International Arctic Science Committee (IASC).

- 40. Arctic Net. “About Us,” accessed April 2, 2021. https://arcticnet.ulaval.ca/vision-and-mission/about-us.

- 41. Caroline Mukusch, “Perspectives from Moscow: The International Arctic Forum,” Second Line of Defense Magazine, October 15, 2010, https://sldinfo.com/2010/10/perspective-from-moscow-the-international-arctic-forum-moscow/

- 42. Roscongress Foundation. “International Arctic Forum in Arkhangelsk Hosts More Than 2,400 Participants from Around the Globe,” Roscongress Foundation, 2017, https://forumarctica.ru/en/news/international-arctic-forum-in-arkhangelsk-hosts-more-than-2400-participants-from-around-the-globe

- 43. Leif C. Jensen and Pål W. Skedsmo, “Approaching the North: Norwegian and Russian Foreign Policy Discourses on the European Arctic” Polar Research 29 (2010): 439–450.

- 44. Pavel Baev, “Russia’s Ambivalent Status-Quo/Revisionist Policies in the Arctic,” Arctic Review 9 (2018): 408–424. https://doi.org/10.23865/arctic.v9.1336.

- 45. Heather Exner-Pirot and Robert W Murray, “Regional Order in the Arctic: Negotiated Exceptionalism,” Politik 20 (2017): 47–64.

- 46. Olga Khrushcheva and Marianna Poberezhskaya, “The Arctic in the Political Discourse of Russian leaders: The National Pride and Economic Ambitions,” East European Politics 32 (2016): 547–566.

- 47. For an analysis of Arctic policies and strategies, see also Heininen et al., “Arctic Policies and Strategies”.

- 48. Beate Steinveg, “The Role of Conferences within Arctic governance,” Polar Geography 44 (2021): 37–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/1088937X.2020.1798540

- 49. Beate Steinveg, “Governance by Conference? Actors and Agendas in Arctic Policy,” (PhD diss., UiT – The Arctic University of Norway, 2021): 180–186.

- 50. Huiyun Feng, “Track 2 Diplomacy in the Asia-Pacific: Lessons for the Epistemic Community,” Asia Policy 13 (2018): 60–66.

- 51. Steinveg, “Governance by Conference”: 152–153.

- 52. Klaus Dodds, “Flag Planting and Finger Pointing: The Law of the Sea, the Arctic and the Political Geographies of the Outer Continental Shelf,” Political Geography 29 (2010): 63–73.

- 53. Tom Parfitt, “Russia Plants Flag on North Pole Seabed,” The Guardian, August 2, 2007, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2007/aug/02/russia.arctic.

- 54. C.J. Chivers, “Russians Plant Flag on the Arctic Seabed,” The New York Times, August 3, 2007, https://www.nytimes.com/2007/08/03/world/europe/03arctic.html

- 55. Hannes Gerhardt et al., “Contested Sovereignty in a Changing Arctic,” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 100 (2010): 992–1002.

- 56. Klaus Dodds and Mark Nuttall, The Scramble for the Poles: The Geopolitics of the Arctic and Antarctic (Wiley, 2015).

- 57. Robert Huebert. “Canadian Arctic Sovereignty and Security in a Transforming Circumpolar World,” in Canada and the changing Arctic: Sovereignty, Security and Stewardship, eds. Franklyn Griffiths, Robert Huebert and W. Lackenbauer (Ontario: Wilfrid Laurier Press, 2011), 55.

- 58. Timo Koivurova, “How to Improve Arctic International Governance,” UC Irvine Law Review 6 (2016): 83–98.

- 59. Wilson Rowe, “Analyzing Frenemies”: 2–3.

- 60. Njord Wegge, “Arctic Security Strategies and the North Atlantic States,” Arctic Review 11 (2020): 360–382. https://doi.org/10.23865/arctic.v11.2401.

- 61. Brigt Dale and Berit Kristoffersen, “Post-Petroleum Security in a Changing Arctic: Narratives and Trajectories Towards Viable Futures,” Arctic Review 9 (2018): 244–261. https://doi.org/10.23865/arctic.v9.1251

- 62. Espen Barth Eide. “Opening Remarks at Arctic Frontiers: The Arctic – The New Crossroads,” Speech at the Arctic Frontiers by the Norwegian Minister of Foreign Affairs, Espen Barth Eide, 2013, https://www.regjeringen.no/en/historical-archive/Stoltenbergs-2nd-Government/Ministry-of-Foreign-Affairs/taler-og-artikler/2013/remarks_frontiers/id713462/

- 63. Arild Moe and Olav Schram Stokke, “Asian Countries and Arctic Shipping: Policies, Interests and Footprints on Governance,” Arctic Review 10 (2019): 24–52. http://dx.doi.org/10.23865/arctic.v10.1374.

- 64. Ólafur Ragnar Grímsson. National Press Club Luncheon with Ólafur Grímsson. Iceland’s President Ólafur Grímsson will address the global race for resources in the Arctic. The National Press Club, April, 2013, https://www.c-span.org/video/?312101-1/president-iceland-global-race-arctic

- 65. Steinveg, “Governance by conference?”: 140.

- 66. Steinveg, “Governance by conference?”: 227.

- 67. Arctic Circle. “Scotland and the New North,” accessed April 2, 2021. http://www.arcticcircle.org/forums/scotland

- 68. Phillip. E. Steinberg and Berit Kristoffersen. “Building a blue economy in the Arctic Ocean: sustaining the sea or sustaining the state?” in Politics of sustainability in the Arctic: reconfiguring identity, space, and time, eds. Jeppe Strandsbjerg and Ulrik Pram Gad (Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge, 2018): 136–148.

- 69. State Council Information Office of the People’s Republic of China. “China’s Arctic Policy,” January 26, 2018, http://english.www.gov.cn/archive/white_paper/2018/01/26/content_281476026660336.htm

- 70. Mark Lanteigne and Mingming Shi. “China Steps up Its Mining Interests in Greenland,” The Diplomat, February 12, 2019, https://thediplomat.com/2019/02/china-steps-up-its-mining-interests-in-greenland.

- 71. Wegge, “Arctic Security Strategies and the North Atlantic States”: 363.

- 72. Ibid.