1 Introduction

The Swedish Supreme Court delivered its verdict on the historic Girjas case1 in January 2020. This article aims to analyse and unwrap this landmark case. The Girjas case could well be described as a “David and Goliath” narrative: a small Indigenous community in a remote corner of the Swedish Far North up against the Swedish State. The battle for the Sami reindeer herding community (RHC) has been hard won; The State, represented by the Office of the Chancellor of Justice, and in particular externally engaged attorneys, explored all available arguments and persisted in using the offensive old term “Laps” instead of the preferred “Sami”.

In a nutshell, this case concerns the exclusive rights of the Girjas reindeer herding community (RHC) to small game hunting and fishing and the authority of the RHC over these rights. The Supreme Court held unanimously that the Girjas RHC has both an exclusive right vis-a-vis the State and the authority to lease hunting and fishing rights to others, something that the reindeer herding legislation clearly prohibits. The full consequences of the decision for both Girjas and other Sami RHCs remain to be seen. In July 2020, the Government declared its intention to establish a public investigation to oversee the need for amendments to the current Reindeer Herding Act of 1971 because of the Girjas case. Pre-hearings occurred during the autumn of 2020 with Sami representatives and others regarding the scope of such an investigation.2 One effect of the Girjas case was, unfortunately, increased racism and conflict between groups of Sami as well as between Sami and Swedish locals.3 These conflicts stem from centuries old Sami politics and the early division between reindeer herding Sami and non-reindeer herding Sami who have no recognised territorial rights.4

The Girjas case did not resolve the tangled matter between those Sami who are RHC members and those who are not. Nevertheless, the case has clarified the conditions for assessing the customary uses of the Sami and their rights to land and natural resources. The case established that in applying national (property) law it is necessary to take into account the protection afforded Indigenous peoples and minorities by binding public international law. Even ILO Convention 169,5 which Sweden has not yet ratified, should, according to the Supreme Court, be considered. We will return to this issue in Section 4.

The 92-page verdict, which is long by Swedish standards, reveals the complexity of the case. In its verdict, the Supreme Court addresses two principal issues: first, whether hunting and fishing rights were based on legislation, and secondly, whether such rights were based on older property law, particularly the doctrine of immemorial prescription. The Court split (3/2) on the first question and the two dissenting judges delivered their own reasoning on this issue.6 The Court was unanimous on the issue of immemorial prescription.7 In this sense it is a strong verdict and establishes an important precedent with respect to the grounds for recognising Sami rights under the doctrine of immemorial prescription, an old Swedish property law concept. While Swedish legal culture and the Constitution require the judge to apply the law and not engage in law-making,8 the Girjas case attests to the fact that, depending on the matter at hand, and the character of the legal sources, elements of law-making may occur in the Supreme Court.

With this backdrop, the aim of this article is to describe, analyse and discuss the Girjas case for an international audience.9 This article unfolds as follows: Section 2 provides general context as well as background for the lawsuit commencing the Girjas case; Section 3 describes in more detail the claims made by the Girjas RHC and matters of evidence; Section 4 summarises the Court’s reasoning regarding the role of public international law; Section 5 addresses issues related to the onus of proof and the principles behind the Court’s assessment of the evidence; Section 6 analyses and discusses the key part of the judgement – the matter of customary law/ immemorial prescription and its relevance for Sami hunting and fishing rights; and finally, Section 7 concludes and discusses our analysis and findings.

2 Context and origin of the Girjas case

The Swedish Government has generally sought to address issues of Sami rights through public commissions and legislative work, but increasingly the Sami are bringing matters related to the recognition and protection of their rights before the courts.10 The Girjas case is part of this trend. The Supreme Court of Sweden has only decided three cases dealing with the recognition of Sami rights: the 1981 Skattefjäll (Taxed mountain) case,11 the 2011 Nordmaling case,12 and the 2020 Girjas case13 – all of which are closely related to reindeer herding rights (Sami RHCs). These decisions have resulted in significant legal developments in Swedish case law.

Like the Girjas case, the Sami initiated the Skattefjäll case by suing the State (in 1966). Their main claim concerned ownership of a large area (skattefjällen) in the county of Jämtland, and the claim that the Sami had stronger rights than those reflected in the applicable reindeer herding legislation.14 Even though the ruling in this case did not favour the Sami, it did clarify the legal nature of the reindeer herding right as a right based on immemorial prescription and, therefore, not dependent upon a statute for its existence. The Supreme Court held that this right was a civil law based right, constitutionally protected against coercive measures without compensation, in the same manner as ownership.

The Nordmaling case concerned the existence of pasture rights for three RHCs during the winter season (October 1 to April 30) near the coastal region south of Umeå, within Nordmaling municipality.15 In 1998 a hundred property owners had sued three RHCs that traditionally pastured their reindeer on private lands, claiming that the RHCs had no acquired rights to use the lands for grazing. The Supreme Court, however, held that the RHCs had reindeer herding rights pertaining to these lands and across the whole municipality based on their historical use, on the basis of customary law.16

Reindeer herding is a vital part of Sami culture and way of living; it is a carrier of traditional knowledge and language.17 Reindeer are semi-domesticated animals and the Sami reindeer herders follow the herd between different seasonal pastures. Therefore, Sami hunting and fishing, for subsistence and for sale, is an integral part of reindeer herding. Some 50% of Sweden’s land surface is subject to reindeer herding,18 and under the usufructuary right to herd reindeer, both public and private estates can be utilised. There are 51 RHCs (sameby in Swedish); each RHC is a legal entity, constituting a geographical area, a form of economic association, and a social community between RHC members.19 It is important to note that “non-reindeer herding Sami” constitute the vast majority of Sami in Sweden. Non-reindeer herding Sami have no State-recognised rights to land and water, even if they still reside within traditional Sami territories. This is the result of nineteenth century state policy and legislation, separating nomadic Sami, especially in the mountainous areas, from other Sami who were assimilated into Swedish society without any special rights.20

Well before the Swedish nation-state was established, Sami livelihoods depended on hunting, fishing, trapping and small scale reindeer herding in the northern part of Sweden.21 Under the cold climate conditions of high mountainous areas and in the vicinity of the Arctic, the Sami developed advanced subsistence strategies over thousands of years. Through a deliberate colonisation process, the Swedish Crown gradually gained control over the traditional Sami territories.22 The complex legal situation of today is the result of successive historical developments and Crown/ State decisions made over time.23 This is particularly true regarding Sami hunting and fishing rights.

The first Reindeer Herding Act, enacted in 1886, introduced a state-administrative system to lease Sami hunting and fishing rights to third parties within the high mountain area.24 The Crown considered that the Sami were not capable or organised enough to operate the leases, and tasked the regional government (the County Administrative Board) to make the decisions, but only after consulting the affected Sami.25 Leases were normally not granted if the Sami would suffer significant harm. The fees benefited both the affected Sami RHC and the so-called Sami Fund, a special fund to support Sami needs more generally.26 Initially, leases to hunt and fish were primarily given to local and regional people. However, interest in hunting and fishing for recreation and tourism gradually increased and, during the 1980s, hunting organisations called for legal amendments to allow the leases to be granted to a larger portion of the population.27

Until the late 1980s the State seems to have viewed the granting of hunting and fishing licenses only as part of an administrative system. But from this period onwards, the State began to claim hunting and fishing rights as part of their landownership, and along with that the right to decide on leases.28 Therefore, the lease system was reformed in 1993, resulting in less influence for the Sami in the decision-making and allowing for a significant increase in the grants allowed in the high mountain areas, not only to Swedes, but also to other European Union citizens.29 The government emphasised that this reform would result in better management of game and fish stocks, and would provide quality recreation experiences to landless hunters at a low cost.

Sami representatives protested strongly against this reform, claiming that the hunting and fishing rights belonged to them exclusively and that they should have considerable influence over the lease system.30 Hunting and fishing by others can cause severe disturbance to reindeer herding, depending on the time period and extent of the grants in a given area. Reindeer may leave an area if disturbed even if the pasture is good. Another impact is that the Sami themselves cannot hunt and fish to the same extent as before.

In 2003 a public commission was set up to propose amendments to legislation regarding hunting and fishing.31 The proposal has not been adopted because of strong opposing interests, as well as an apparent reluctance among politicians to strengthen Sami land rights.32 International human rights bodies have repeatedly criticised Sweden’s failure to address Sami land rights.33 Following this critique Sweden has been, among other things, called on to properly demarcate traditional Sami land areas and adopt legislation that recognises and protects Sami land and resource rights, as well as secures legal aid to allow Sami to assert their rights before the courts.

Against this background, the Swedish Association of Sami prepared a lawsuit aiming to clarify the extent of RHCs’ hunting and fishing rights. In May 2009, the Association and Girjas RHC took legal action against the Swedish State. Girjas RHC is situated within the county of Norrbotten, in the northernmost part of Sweden. Eighteen reindeer herding family groups live in the Girjas RHC. The community has approximately 120 individual members, but an additional 400 Sami in the local area have a social relationship with the Girjas RHC.

The Girjas case is unique in many ways. There are no equivalent decisions in other Nordic countries. While Indigenous hunting and fishing rights cases may be more common in other jurisdictions, such as Canada, these cases have often arisen in connection with the defence of criminal or quasi-criminal charges. This is true of many of the key decisions of the Canadian Supreme Court, including Sparrow, Marshall and Bernard and Adams.34

3 The Area, claim and evidence

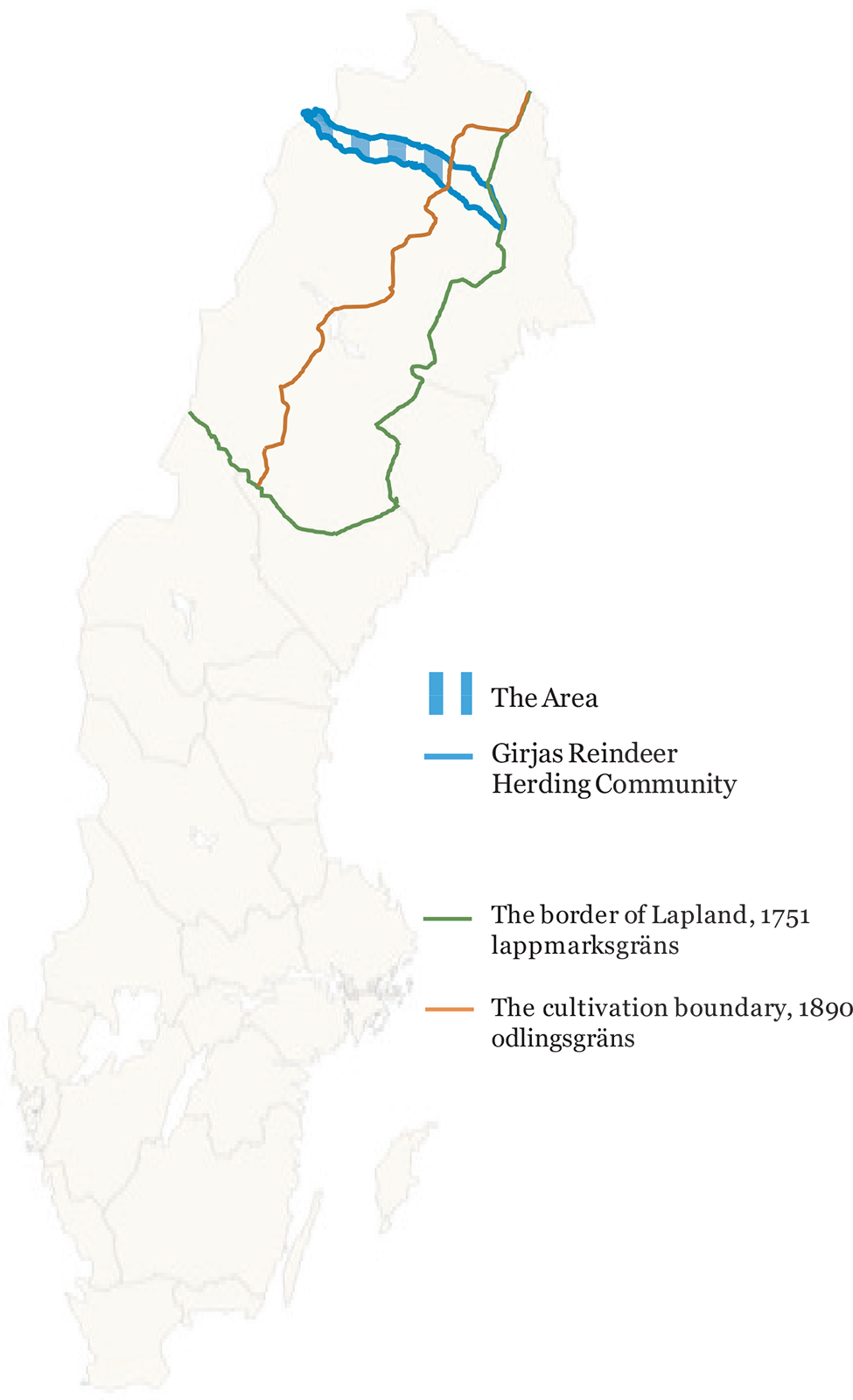

The claim area (henceforth the Area) deals with land for which the State has been the registered owner since 1956.35 The claimants made a deliberate choice not to claim ownership rights. This vast estate, essentially undeveloped, encompasses 3,500 square kilometres. The Girjas RHC grazing lands form a major part of the estate. Notably, the Girjas case concerns an area west of the so-called cultivation boundary, finally established by Parliament in 1890.36 The rationale behind the decision was to resolve land use conflicts between settlers and the Sami. Lands west of this boundary were to be reserved for traditional Sami land uses, lands to the east were to be available for cultivation. This boundary is legally important since the current Reindeer Herding Act refers to this administrative boundary; it is generally considered that Sami rights are stronger west of the cultivation boundary. This coincides with the claim area chosen for the lawsuit against the State.

The Girjas RHC claimed, firstly, exclusive small game hunting and fishing rights within the Area, meaning that the Swedish State could not administer hunting and fishing leases in the Area and that the RHC could decide on such leases without the consent of the State. As an alternative, the RHC claimed, secondly, that hunting and fishing leases in the Area should be decided jointly by the Girjas RHC and the State.37 The State rejected both claims.38

To support their claims the Girjas RHC argued that they had used the land since time immemorial, continuously and without competition or protests from others. As a result, and in relation to the State, the RHC had acquired exclusive small game hunting and fishing rights in the Area. The Girjas RHC presented two alternative legal grounds for the exclusive hunting and fishing rights: (1) these rights followed directly from the reindeer herding legislation (and the associated preparatory works for both the current and previous versions of the Act), and, (2) these rights were acquired because of protracted use and based on customary law or immemorial prescription, which should, following the RHC’s argument, be assessed based on an understanding of the Sami as an Indigenous people.39

Additionally, the Girjas RHC argued that the present leasing system (Reindeer Herding Act, ss. 31–34)40 violated the Constitution (discriminatory and undermined the protection of their property)41 and the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) (on the same grounds).42 Hence, Girjas argued that these provisions (ss. 31–34) should be disregarded. The State accepted that if the Court were to find that the Girjas RHC had exclusive hunting and fishing rights,43 then these provisions should not be applied to the Area.44 An unfortunate consequence of this concession was that the Court assessed neither the constitutional argument nor the argument based on the ECHR.45 Such an assessment would have benefited the development of law in this area.46

Before commenting on the evidence presented in this case, it is important to comment on the first legal ground raised by the RHC, namely that their exclusive right follows directly from the reindeer herding legislation. Because of procedural law, the Supreme Court had to examine this legal ground first, and as indicated above, the Court was split (3/2). Based on the same legal material (present and past reindeer herding acts and their associated preparatory works), the majority and minority came to completely different conclusions,47 which suggests that this material is too uncertain to give definitive answers. The majority held that the reindeer herding legislation did not afford exclusive rights for the Girjas RHC, but instead concluded that the legislation was built on the idea that these rights belong to the State.48 By contrast, the minority held that this legislation did manifest exclusive hunting and fishing rights for the RHC (and indeed for all Sami RHCs in Sweden, following this line of argument). Since the precedential value of this part of the judgement is weak, we will not comment further on this point.49

The core of the case concerned how Girjas had utilised the landscape and resources over time as well as how the State had responded and acted. The two parties presented an enormous amount of historical evidence, primarily written public material (investigations, government bills, court protocols and church records) on these points. The two parties interpreted this material differently and they presented contradictory versions of the Area’s historical development. Indeed, evaluating evidence about historic land use became a central part of the Court’s assessment. According to the Court, the evidence provided only modest information regarding the historical and customary uses of the Sami within the Area, and did not reveal the Crown’s attitude towards the Sami uses.50 Therefore, the Court also considered evidence from Lapland51 generally (cf. Figure 1 above), as well as from areas adjacent to the Area. Given the complex situation regarding historical evidence, this is an important relaxation of the evidentiary rules that will reduce the burden on those litigating such history-based cases in the future.

Both parties also called expert witnesses from different scholarly disciplines, such as history, law and historical ecology. Members of the Girjas RHC were also heard as witnesses. Denied a visual inspection of the claim area, the RHC presented a film of the Area from a helicopter along with an accompanying commentary by one of the elders.

In line with Swedish procedural law for civil cases, the main rule is that there are no restrictions on the admissibility of evidence, and the courts are free to assess both the relevance of and the weight to be accorded to that evidence.52

4 The importance of international Indigenous and minority law

In this case, the Court referred to the role of international Indigenous and minority law on several occasions, and these references clearly influenced the Court’s decision in many respects. These references are surprisingly clear and indeed welcome.53 The Court also addressed ILO Convention 169.54 Sweden has discussed ratification of ILO Convention 169 for decades but has refrained from doing so mainly because of potential Sami land rights to a vast area rich in natural resources, including water, minerals and timber.55 The Court’s emphasis on the international law standards protecting Indigenous peoples was unexpected; Swedish law adopts a dualistic tradition concerning the relationship between domestic and international law.

Since 2010 the Sami have been constitutionally recognised as an Indigenous people. The amended section of the Constitution provides that “[t]he opportunities of the Sami people and ethnic, linguistic and religious minorities to preserve and develop a cultural and social life of their own shall be promoted” (emphasis added).56 The addressee is clearly the State, and the State (as lawmaker) is obliged to act to secure the protection and development of Sami conditions and cultures. In this case the Court declared that the provision does not create any individual rights,57 but does reflect international law principles to safeguard the rights of ethnic minorities expressed in a number of international treaties to which Sweden is a party.58 The Court reiterated that even if Swedish law normally requires the incorporation of a treaty in order to give the treaty domestic effect, it was “natural” that public international law principles would be taken into account in the interpretation of current Swedish law.59

In regards to the RHC’s second legal ground, rights based on immemorial prescription, the Supreme Court reiterated the importance of international law, particularly Indigenous peoples’ customs and customary laws.60 Following ILO Convention 169 Article 8.1,61 the Court held that in applying domestic law, due regard shall be taken to Sami customs and customary laws. Even though Sweden has not ratified the Convention, the Court held that the treaty in this respect gave expression to a public international law principle.62 The Court seems to argue here that a recognised Sami custom constitutes an a priori right to the area in question. Moreover, the Court refers both to Article 26 of the UNDRIP,63 regarding Indigenous peoples’ rights to their lands, territories and resources they have traditionally owned, occupied or otherwise used, and Article 27 of ICCPR64 dealing with the right of minorities to enjoy their own culture. The Supreme Court concluded that international case law has attached significant meaning to the customary principles of Indigenous peoples and this entails that Sami customs in Lapland shall also be accorded due regard.65 See further Section 6.

The Court’s references to Indigenous customs and public international law are significant. It is novel for the Supreme Court in a Sami rights case to ground its decision in international human rights law, especially in the context of domestic property law. To pay due regard to Sami customs is one aspect of ensuring that Swedish application of law is in accordance with international law requirements.66 The Court also referred to ILO Convention 169 in the context of evidence as the next section demonstrates.

5 Burden of proof and the evaluation of evidence

An important aspect of this case is the Court’s statements on the burden of proof, evidentiary requirement and evaluation of evidence.67 In Swedish case law and legal literature it is common to separate onus of proof from the evidentiary requirement, even if, in a practical sense, they form a concatenated whole.68 The matter of evidentiary requirement and how evidence should be evaluated in Sami law cases has been undeveloped and uncertain given the few Supreme Court cases.

The precedential value of the Court’s statements on burden of proof and related issues for future cases concerning Sami territorial rights is strong. The Court is unanimous in this part. First, as is normal in Swedish civil law cases, the burden of proof rests on the claimant and the Court concluded that there are no reasons to shift that burden in this sort of case.69 Hence, Girjas RHC had the burden of proof for the elements that established Sami rights based on protracted uses relating to the Area.70 What is new here is that the Court places the burden of proof on the State regarding any circumstances that could cause such Sami rights to cease.71 After a Sami right is established, the State must prove that the right in question is extinguished either though legislation or expropriation – and importantly, this extinguishment must be “clear and definitive”.72 Interestingly, there are similarities to the test on extinguishment developed by the Supreme Court of Canada, where a “clear and plain” intention of the Sovereign must be established to extinguish an existing aboriginal right.73

Second, with respect to evidentiary requirements, the Court held that it was necessary to practice a certain “evidentiary relaxation” in Sami law cases; a RHC should have reasonable opportunity to prove rights associated with their traditional territories.74 Here the Court referred to Article 27 of UNDRIP and Article 14.2 of ILO Convention No. 169. The Supreme Court pointed to the fact that this case concerned a claim made by a RHC against the State, and that the community represented an Indigenous people.75

Moreover, the Court stressed that the case involved difficult historical circumstances, accentuated by the oral nature of the Sami culture. Consequently, it is significantly easier for the State to document historical events and legal attitudes. Hence, the Court held that when the Sami party fulfils its onus of proof, certain inconsistences in the historical material may be accepted. Any such deficiency could also be “supplemented by reasonable assumptions” relating to circumstances applicable in other parts of Lapland or situations during adjacent time-periods.76 Furthermore, the Court did not require the RHC to determine which individuals had established hunting and fishing rights historically or how these Sami rights have been transferred to succeeding generations. The Court applied this relaxed approach to assess the historical material, the burden of proof and evidentiary weight as they examined the historical events and actual land use over different periods within the Area.77

Third, in relation to the evaluation of evidence, the Court highlighted obvious difficulties: incomplete historical documentation and the majority of documents stemming from courts and administrative authorities. It was therefore reasonable to assume that contemporary Sami customs were not reflected in these documents, or that they were reproduced in a faulty manner. The Court also cautioned that in cases where the law was unclear, administrative authorities may well have interpreted matters to the advantage of the State, especially regarding fiscal interests.78 The Court mentioned that the historical documentation and literature relating specifically to the Area was scarce and that available documentation principally was related to other areas in Lapland. When taking into account such documentation it was important to be cautious because, as the Court emphasised, there may be differences between different areas and groups of Sami, and between different time periods.79 In particular, the Court underlined that the Area was one of the most remote areas of Lapland, where it could be assumed that Swedish authority was established rather late. The rivalry over land uses between Sami and other local groups were also assumed to be lesser in the Area than in other parts of Lapland.80

All in all, this section of the case forms an important backdrop for the Court’s ultimate assessment of the historical and other evidence. One could say that the Court laid a foundation for a presumption, on the basis of this Area’s remoteness, that the Sami historically have had a considerable degree of autonomy with few competing land uses. And, in addition, we understand the Court to have suggested that the lack of specific knowledge on historical events and Sami customary uses within the Area should not be interpreted against the claimant Sami community.

6 Assessment of protracted uses: has the land use of Girjas reindeer herding community been exclusive?

6.1 Summary

The key issues in the Supreme Court’s assessment concerned whether the Girjas RHC – in relation to the Swedish State – has an exclusive right to lease their small game hunting and fishing rights to others, based on their longstanding land and water uses. In sum, the Court unanimously upheld the claim by the Girjas RHC to the Area,81 and to the RHC’s right to lease those rights without seeking the consent of the State.82 As a result, the State does not possess the hunting and fishing rights that traditionally accrue to the landowner.83 For future cases involving Sami claims of territorial rights this will mean that: (1) the historical and protracted land uses of the RHC shall be measured against immemorial prescription, not customary law; (2) the claims must be based on the historical conditions and circumstances applicable to each area, and, (3) the form of immemorial prescription must be culturally adjusted to reflect how reindeer herding, hunting and fishing traditionally are performed with all their defining characteristics. The principles of immemorial prescription must also be adapted to international Indigenous and minority rights.

The core of the Court’s decision is the application of the principles of immemorial prescription and to this we turn next.

6.2 A key question: Should customary law or immemorial prescription be applied?

Following the Nordmaling case,84 released by the Supreme Court in 2011, there was confusion as to whether subsequent cases dealing with claims to Sami territorial rights would be assessed according to customary law or immemorial prescription (see Section 2).85 In the Nordmaling case, the Supreme Court based their assessment on “customary law” as a way to avoid the more stringent rules on immemorial prescription. The written rules of immemorial prescription are found in the Land Code of 1734; they target settled lifestyles and visible land uses, whereas customary law is unwritten and thus easier to adapt. As a concept, Swedish customary law had not been applied in the context of property law in modern times.86 In the very few earlier Sami law cases,87 including the lower courts in the Nordmaling case, immemorial prescription had been applied. This doctrine relates to the autonomous acquisition of rights through protracted land uses. In earlier times customary law had been applied as a complementary, and weaker, legal source in Swedish law. In essence, should customary law be used as the normative basis for the acquisition of Sami rights, there was a risk of the rights being “watered down”.

The Supreme Court in the Girjas case clarified that the assessment must originate from the doctrine of immemorial prescription to determine whether Sami, based on protracted uses, have acquired rights to land.88 This statement has precedential force,89 and applies regardless of whether the claimed rights are situated in the mountainous areas or winter pasture closer to the more populated coastal areas.90 A legitimate question is of course why one should apply immemorial prescription before customary law. The Court observed that customs and customary law have had weak status as legal sources in Swedish law and have normally only been applied in tandem with another legal sources.91 In the Nordmaling case, the Supreme Court, however, applied customary law similar to an autonomous proprietary concept, based on a set of conditions that over time may, if they are met, lead to acquisition of rights related to certain tracts of land.

To the extent that Swedish law historically used proprietary doctrines, immemorial prescription has been applied to assess right-claims based on protracted uses, and therefore, the Supreme Court argued, one should first apply immemorial prescription.92 This is also, the Court pointed out, the view taken by the Swedish legislator when amending the Reindeer Herding Act declaring that reindeer herding rights are based on immemorial prescription. However, according to the Court, where the conditions pertaining to immemorial prescription cannot be applied “in a reasonable manner”, one may instead apply customary law.93 The Court also observed that the distinction between immemorial prescription and customary law is blurred: both concepts embrace the idea that long-standing and respected circumstances should not be disrupted. An application of immemorial prescription should thus strive to take into account customary laws in historical times (if known). The Court considers that this corresponds with Sweden’s international law obligations.94

In its reasons the Court established a flexibility and a basic understanding of the complexity of assessing Sami customary uses in Swedish law that were not evident in the two previous Supreme Court cases (Nordmaling and Skattefjäll).95 Future courts dealing with Sami rights’ claims should begin with immemorial prescription, but may turn to apply customary law if it leads to more reasonable outcomes.

While the importance of international law relating to Indigenous peoples and minorities is evident throughout the judgement, the Supreme Court implicitly links “unreasonable” applications of Swedish law with the historical invisibility of Sami rights and Sweden’s colonial legacy. This is significant. We also read this case as an attempt by the Supreme Court in Girjas to merge its judgement and reasoning with the Nordmaling case, which also has precedential character, especially with respect to including reindeer herding practises in the legal assessment. Both Girjas and Nordmaling represent tremendously important steps in developing Swedish Sami law.

6.3 The conditions for protracted uses by Sami

Immemorial prescription had its glory days in the 1600s and 1700s and has since hardly been applied before Swedish courts. The doctrine was annulled by the new Land Code in Sweden in 1972 as an outdated concept, but transitional rules allow for the recognition of already acquired rights, Sami as well as other property rights. While application of the doctrine turns on “possession” of a tract of land,96 it had earlier been demonstrated that it was difficult to prove Sami nomadic land uses before courts. An important step forward, following the Nordmaling case, was taken by the Supreme Court in Girjas. Although the Supreme Court in Girjas refers to the old provision on immemorial prescription in the repealed Land Code of 1734,97 it is obvious that the Court has a broader interpretation of the doctrine. The Court differentiates between “traditional forms of immemorial prescription” and the “special kind of immemorial prescription” that this case concerns.98 Traditional immemorial prescription concerned small land areas that were used intensively, primarily for cultivation; the land use had to be continuous, of a certain intensity and over at least 90 years.99

The Supreme Court emphasises the particular difficulties that arise when immemorial prescription is applied in its traditional form to Sami land use, and underscores that the possibility to have Sami right’s claims recognised cannot be “merely theoretical”.100 Hence, the conditions for proving Sami rights based on immemorial prescription must give room for “a more independent assessment”, especially concerning usufruct rights, in order to address the legitimate claims on traditional land uses that the Indigenous Sami may have.101 In moderating the traditional criteria of immemorial prescription, the Court refers to the more relaxed conditions established in the Nordmaling case relating to customary law.102 It is notable that the Supreme Court in Nordmaling borrowed certain conditions from immemorial prescription for informing their assessment of rights based on customary law.103 What we see is a cross-fertilisation between the rules for immemorial prescription and customary law in the two cases, compounding the indistinctiveness between the two concepts, but at the same time increasing flexibility.

By specifying more relaxed criteria for assessing the Girjas RHC’s land and water uses over time, the Court turns away from the stipulated cumulative conditions in the old provision in the Land Code. The Court makes this clearer when towards the end it summarises its assessment of the situation up to the mid-1700s: the Sami at the time had exclusive hunting and fishing rights because they had “during long time, continuously and without protests from either the Crown or others” practised hunting and fishing in the Area, and their leasing of hunting and fishing to others “had not been questioned”.104

Hunting and fishing (in combination with reindeer herding) can thus establish hunting and fishing rights even if the land and water uses have been rather extensive and related to a larger area, but such uses must nevertheless have been relatively recurrent.105 The established criteria of “undisputed and unhindered” for immemorial prescription must be applied, according to the Court, regardless of whether the land use was related to populated areas or uninhabited and remote areas. For instance, the State may also hinder land uses evolving into rights in remote and sparsely populated areas.106 The assessment of all conditions together, stipulated by Nordmaling for customary law, shall also apply for immemorial prescription, and be assessed according to how reindeer herding (and hunting and fishing) is actually carried out, and taking into account the specific features of the culture. The Supreme Court declared, with reference to Nordmaling, that such features can include the long cyclical movements with the herd as well as biological and weather-related conditions.107

We emphasise that such an assessment of all this evidence for immemorial prescription is crucial, especially where the historical evidence may be inadequate, ambiguous or sometimes lacking (see Section 5). A court may assess all evidence in total: age-old land use may, for instance, compensate for less intensive land use.108

Importantly, the Court also starts its assessment in ambiguous prehistoric times to determine at what time Sami hunting and fishing rights were acquired; it does not work backwards 90 years from the present day, which is the “normal” approach. See below Subsection 6.4.

Regarding the condition for exclusive hunting and fishing rights, the Court reasoned that there cannot exist general answers; the evidence needs to be assessed on a case-by-case basis focusing on historical use and other circumstances, including the geography and climate in a region.109 The Court declared that if a right is held to be an exclusive right, then normally it should be assumed that this right also includes a right to grant leases to others.110 The land and water uses by the ancestors of the Girjas RHC proved that the rights were indeed exclusive rights which carried the right to lease.

6.4 The Court’s assessment of historical evidence and Sami land and water uses

This subsection summarizes how the Supreme Court assessed the land and water uses by the Sami, on the basis of immemorial prescription over different time- periods. The assessment spans more than 17 pages.111

The Court acknowledged, first, that there has been a Sami population in Lapland since far back in time, and also in the Area (at least back to the Iron Age). The evidence did not provide conclusive information regarding conditions in the Area before the end of the Middle Ages, such as customary rules on land and water uses or whether there were other peoples living in the Area. The Crown sought to expand its dominium to Lapland, but it was not possible to establish that Swedish laws were applied in the Area. The Court instead assumed that during the Middle Ages the Sami applied Sami customary law to regulate their affairs. Hence, during these early times, it was not possible to say whether the Sami in the Area had established any rights (individually or collectively) that could have legal relevance today.112

The situation was different from the second half of the 1500s and onwards. The Court concluded that during this time, the Swedish Crown had established supremacy over Lapland and the Area, and henceforth the assessment of the law – and acquisition of rights – should be based on historical Swedish law for each following time-period. This meant an application of the principles of immemorial prescription, including the more relaxed rules for its assessment.113 See Subsection 6.3 above.

Following the assessment, the Court held that, at least by the mid-1700s, the Sami had acquired an exclusive right – vis-a-vis the Crown – to hunt and fish in the Area. This also included the right to grant leases of these rights to third parties. At this time the strength of this right was equivalent to present-day hunting and fishing rights. The right was founded on the age-long and continuous use of the lands and waters in the Area by the Sami,114 and was practised without protests from the Crown or others.115 To clarify, the Sami had a right based on immemorial prescription. The hunting and fishing rights were held by the Sami for each time-period; and the Court did not require the Girjas RHC to provide details on which Sami families and individuals engaged in these activities.116

A specific matter for the Court concerned what consequences were to be attached to the fact that the Crown, since the second half of the 1600s, had repeatedly claimed that Lapland belonged to the Swedish Crown and that hunting and fishing rights were already at this time-period coupled with ownership to land and shore. The Court concluded that this circumstance lacked legal meaning, since the Crown had not made protests in a manner that would have hindered the acquisition of hunting and fishing rights based on immemorial prescription; they were too indeterminate and were not focussed on hunting and fishing.117

In the years leading up to the enactment of the first reindeer herding act in 1886 there was a gradual decline in the Sami legal and political position in Sweden, through legislation and various State decisions and policies. However, no measures were sufficiently “clear and definitive” to allow the Court to reach the conclusion that established rights had ceased to exist or that the right to control the hunting and fishing had been extinguished.118 There are no records from this time to show that the Crown had limited Sami hunting and fishing rights, or that the Crown practised their own hunting and fishing in the Area or adjacent areas, including by leasing rights. The Sami had not of their own accord remitted their rights, but instead have continued to practice reindeer herding, hunting and fishing.119 This right, that pre-legislation in 1886 belonged to each individual Sami, was, via legislation, transferred to the members of the Girjas RHC.120

The Court held that the issuing of hunting and fishing leases to others belongs to the Girjas RHC, which is the entity that can exercise control. In line with general principles of co-owned property, the Court declared that it was the association created to manage the common interests of the members (the RHC) that is the right-holder, not the individual members. Furthermore, the Court stated clearly that Girjas RHC can grant these rights without the consent of the State, and, accordingly, the State cannot continue to issues leases in the Area.121 As a result of this decision, the regional authority responsible for granting hunting and fishing licenses – the County Administrative Board in Norrbotten – closed the administrative system for the Area on the same day the Supreme Court released its decision, 23 January 2020.

7 Conclusion

The Girjas case is a decision of historical importance in Sweden in several respects. This is the first case in which the Sami have succeeded against the State in a civil law case. Together with the 1981 Skattefjäll case, it represents one of Sweden’s largest and most complex cases in modern times.122 A loss for Girjas would have meant that the Swedish State could continue to decide on the leases of hunting and fishing rights, without any major consideration of the needs of Girjas RHC. It would also have meant that it would have remained unclear whether this form of state decision-making limited the recognised property rights of the RHC, and Swedish Sami rights more generally. The Girjas case also needs to be understood in its specific historical and legislative Swedish context. In the other Nordic countries, Finland and Norway, Sami hunting and fishing rights are addressed differently. Nevertheless, it should be made clear that since Finland shares the provision on immemorial prescription in the former Swedish Land Code – Finland was part of the Swedish Kingdom and administration until 1809 – the Girjas case could also have legal relevance for the recognition of Sami reindeer herding rights in Finland.

The Girjas case has precedential value for how Sami reindeer herding rights (which include hunting and fishing), and possibly other Sami right’s claims, are to be assessed in the future. The protracted uses by the Sami shall be determined according to immemorial prescription, but mindful of international law protecting Indigenous peoples and minorities, as well as other adjustments declared by the Supreme Court. Despite its divided verdict (3/2), the important parts of the Court’s decision are unanimous, namely how the historical land-uses and evidence is to be assessed and interpreted. This is a significant legal development. In summary, here are the most important steps made by the Supreme Court.

First, and perhaps most essentially, the Court held unanimously that international law (even including ILO Convention No. 169, which Sweden has yet to ratify) which protects the rights of Indigenous peoples and minorities is of vital importance in cases like Girjas. In its discussion on immemorial prescription, the Court referred to Article 8.1 and Article 14.2 of the Convention, and concluded that Article 8.1 (Indigenous customary norms) expressed a general principle of law. In addition, the Court referenced UNDRIP Articles 26 and 27 (despite its non-binding nature) and recognised that it has legal relevance in cases like this, calling for “evidentiary relaxation” in Sami law cases.

The Court considered that despite the fact the Swedish law adheres to the dualistic principle, it was natural that public international law principles influence the interpretation of domestic law even where such norms have not been transposed via legislation.123 This is an enormously significant step taken by a Court in Sweden. The Supreme Court repeats in several places in its decision that the Sami are an Indigenous people (and ethnic minority) and thus warrant special protection because of their status.

Secondly, this case clarified that the historical land-uses by Sami shall be determined according to the old proprietary doctrine of immemorial prescription, not “customary law”. This issue was left hanging after the 2011 Nordmaling case and has now been resolved. Only where immemorial prescription cannot be applied in a reasonable manner, should old customary law be applied. The reasons behind this statement are of particular interest. The Court’s main reason is the fact that Swedish law has historically applied immemorial prescription, which is the doctrine that relates to the autonomous acquisition of rights through protracted land and water uses. Customary law has in earlier times, for the most part, been applied as a complementary legal source – and most importantly, has had a weak position in Swedish law. In essence, reindeer herding rights risked being “watered down” by an application of customary law.124

The Court’s assessment begins in prehistoric times, in the Iron Age and Middle Ages, and then the Court successively assesses the evidence through to the present. The Court held that, at the latest, during the mid-1700s the Sami had developed a right to control their hunting and fishing rights, and that this right has not been extinguished. This mode of proceeding (instead of going back 90 years from the present time, the traditional approach to immemorial prescription) is significant. A century back takes us to the time period where assimilation policies were strong and the perception of Sami rights were the weakest, thereby bypassing the strong legal position that the Sami had acquired before the Crown’s sovereignty and power aspirations had become more pronounced and settled.

Furthermore, the Supreme Court has drawn the contours of a specific form of immemorial prescription, where certain adjustments are called for.125 For instance, domestic Sami customary norms shall be observed to ensure that Swedish application of law corresponds to international standards protecting Indigenous peoples. A central condition for applying immemorial prescription was that an assessment of a priori right shall be according to the actual land uses performed over time, that is, how traditional reindeer herding is managed and the migratory nature of the reindeer. In its assessment of exclusive rights, the Court held that such evaluation should not only consider competing land-uses over time, but also the claimant’s need of the goods (game and fish). Immemorial prescription must allow for a full assessment of all evidence taken together.

Thirdly, an important novelty in this case is the need to adjust the assessment of the referenced evidence. The Court declared that while historical circumstances determine the outcome of the Court’s assessment, a lack of information and circumstances that are difficult to investigate, were seen as problematic. The Court established that evidentiary rules should be relaxed in cases like this; it must be possible for a RHC to have a reasonable opportunity to prove its case and have its rights recognised. Where the evidence is incomplete or fragmentary, those deficiencies may be healed in the Court’s assessment through “reasonable assumptions”. This means that historical evidence drawn from other parts of Lapland, or similar situations during adjacent time periods, can fill out the gaps for historical circumstances in the area of the claim. A novelty is also that the State has the burden of proof regarding circumstances that could cause such Sami rights to cease. The State must prove that the right in question is extinguished, through legislation or expropriation, and this extinguishment must be “clear and definitive”.126 This proof was not met by the State in this case, despite the fact that the Court pointed out that different measures over time had significantly weakened the legal position of the Sami.

Regarding the evaluation of evidence the Court acknowledges the special circumstances relating to the historical material. The documents consists mainly of public material from State authorities and courts, and the Court acknowledged that an unclear position on the law may have been interpreted in favour of the Crown. Moreover, Sami customs have most likely not been reflected in these documents, or have been inaccurately reproduced. Therefore, these documents are not likely to give an accurate account of the legal development. Hence, the Court reasoned that caution was called for in assessing this evidence. The Court noted, furthermore, that historical research published during the 1900s includes dissenting opinions on what rights (if any) the Sami had acquired throughout history, and this fact calls for caution with respect to evaluation of the evidence.

Finally, it should be pointed out explicitly that the Girjas case did not concern ownership to the Area; this was not part of the trial. It was a conscious choice by the Girjas RHC that their claim would only allege exclusive hunting and fishing rights and control over these rights. Since 1956 the State has the formal title deed for the estate where the RHC has its main pastures.127 However, the Girjas RHC has not certified or accepted State ownership of the Area, an issue that remains contested.

At the time of writing, the Girjas case has yet to have an impact on other RHCs in Sweden regarding their hunting and fishing rights. It is likely that new lawsuits will follow, depending on how the recently initiated public investigation is set up and concluded. In such trials, the Girjas case will, of course, be of crucial importance, and we anticipate that the outcome for several RHCs with grazing areas in the northern mountains will be the same as for Girjas, namely that the RHC in question has exclusive hunting and fishing rights including a right to lease these rights to others. Nonetheless, the situation is complicated and not all RHCs are interested in running an administrative leasing system by themselves.

Acknowledgements

We wish to extend our warm thanks to the anonymous reviewers for valuable comments to an earlier version of this article. This article has been written as part of the project “Sami traditional livelihoods, competing land uses, competing legal sources” (SaCC) at the UiT The Arctic University of Norway, financed by the Research Council of Norway (Project No. 259418).

NOTES

- 1. Swedish Supreme Court Case No. T 853-18, decided 23 January 2020. Hereinafter referred to as Girjas v. the State, and the specific paragraphs of the case.

- 2. See the press release from the Government (Ministry of Enterprise and Innovation) at https://www.regeringen.se/pressmeddelanden/2020/09/sakrad-och-moten-om-oversyn-av-rennaringslagstiftningen/ (accessed January 11, 2021).

- 3. Examples of these conflicts, reported by local media, were killings of reindeers of the Girjas RHCs and threats against reindeer herders. See e.g. Swedish Television news (SVT) at https://www.svt.se/nyheter/inrikes/hot-och-trakasserier-mot-samer-efter-girjasdomen (accessed January 11, 2021).

- 4. See, e.g. Ulf Mörkenstam. “The Power to Define: The Saami in Swedish Legislation,” in Conflict and Cooperation in the North, eds. Kristiina Karppi and Johan Eriksson (Umeå: Norrlands Universitetsförlag, 2002), 113–45.

- 5. International Labour Organization (ILO), Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention, C169, 1989.

- 6. Girjas v. the State, paras 98–166.

- 7. Girjas v. the State, last page of the dissenting opinion.

- 8. Christina Allard, “Some characteristic features of Scandinavian laws and their influence on Sami matters,” in Indigenous Rights in Scandinavia – Autonomous Sami Law, eds. Christina Allard and Susann Funderud Skogvang (Farnham: Ashgate, 2015), 52.

- 9. Our discussion draws upon our Swedish case analysis. See Christina Allard and Malin Brännström, “Girjas sameby mot staten: En analys av Girjasdomen,” Svensk Juristtidning (2020): 429–52.

- 10. Christina Allard, “Some characteristic features of Scandinavian laws,” 51; Malin Brännström, “Court proceedings to evaluate the implementation of Sami land rights in Sweden,” Retfaerd 2 (2018), 42; Malin Brännström. “The Girjas Case – court proceedings as a strategy to enforce Sámi land rights“, in Routledge Handbook of Indigenous Peoples in the Arctic, eds. Timo Koivurova, Else Grete Broderstad, Dorothee Cambou, Dalee Dorough and Florian Stemmler (London: Routledge, 2021).

- 11. NJA 1981 p. 1.

- 12. NJA 2011 p. 109.

- 13. NJA 2020 p. 3.

- 14. See further Christina Allard, “Two Sides of the Coin: Rights and Duties. The Interface between Environmental Law and Saami Law Based on a Comparison with Aoteoaroa/New Zealand and Canada” (PhD diss., Luleå University of Technology, 2006), 258–62.

- 15. See Christina Allard, “The Swedish Nordmaling case,” Arctic Review on Law and Politics 2 (2011): 225–28.

- 16. It should be noted that a provision in the Reindeer Herding Act declares that herding on winter/spring-areas can be carried out on areas used ‘of age’ (av ålder), thus giving statutory recognition to custom. Interestingly, customary law had not been applied in the context of real property for quite some time.

- 17. See Kaisa Raitio, Christina Allard and Rebecca Lawrence, “Mineral extraction in Swedish Sápmi: The regulatory gap between Sami rights and Sweden’s mining permitting practices,” Land Use Policy 99 (2020): chapter 3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2020.105001.

- 18. Per Sandström, “A Toolbox for Co-production of Knowledge and Improved Land Use Dialogues: The Perspective of Reindeer Husbandry,” (PhD diss., Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, 2015): 15.

- 19. Each RHC has a name, e.g. Girjas RHC. For geographical location of the RHCs, see https://www.sametinget.se/8382 (Accessed September 25, 2020).

- 20. See e.g. Mörkenstam, “The Power to Define.”

- 21. Ingela Bergman, Olle Zackrisson and Lars Liedgren, “From Hunting to Herding: Land Use, Ecosystem Processes, and Social Transformation among Sami AD 800–1500,” Arctic Anthropology 2 (2013): 25–39.

- 22. Nils Johan Päiviö, “Från skattemannarätt till nyttjanderätt. En rättshistorisk studie av utvecklingen av samernas rättigheter från slutet av 1500-talet till 1886 års renbeteslag,” (PhD diss., Uppsala University, 2011): 250–57.

- 23. Johan Strömgren. “The Swedish State´s Legacy of Sami Rights Codified in 1886,” in Indigenous Rights in Scandinavia – Autonomous Sami Law, eds. Christina Allard and Susann Funderud Skogvang (Farnham: Ashgate, 2015), 95–110.

- 24. Reindeer Herding Act of 1886, ss. 22 and 23.

- 25. See the bill “Förslag till förordning angående de svenska Lapparne och de bofasta i Sverige samt till förordning angående renmärken afgivna af den dertill utaf Kongl. Maj:ts förordnade komité 1883.”

- 26. Reindeer Herding Act of 1886, s. 22.

- 27. Agneta Arnesson-Westerdahl, “Beslutet om småviltjakten: en studie i myndighetsutövning,“ Report from the Swedish Sami Parliament (1994): 16–18.

- 28. Prop. 1986/87:58 om jaktlag, 45. “Prop” refers to a Government bill, followed by the year of issue and a serial number.

- 29. Prop. 1992/93:32 om samerna och samisk kultur, 141.

- 30. Arnesson-Westerdahl, “Beslutet om småviltjakten,“ 33–34. In 1995, Sami representatives filed a lawsuit at the European Commission of Human Rights, arguing that the Swedish law infringed their property rights as protected by Article 1, Protocol 1 of the European Convention on Human Rights, 1950. The Commission found however that the applicants had not exhausted all national remedies (Article 35) with respect to their civil rights. Hence, this serves as a backdrop for the lawsuit at the local court in the Girjas case. See Könkämä Sami villages and others v. Sweden, 1996, The European Commission of Human Rights, App. No. 27033/95.

- 31. See the summary commission report SOU 2005:116 Jakt och fiske i samverkan. For a dicussion on such rights for non-reindeer herding Sami see Eivind Torp. “Sami hunting and fishing rights in Swedish law,” in Indigenous Rights in Scandinavia – Autonomous Sami Law, eds. Christina Allard and Susann Funderud Skogvang (Farnham: Ashgate, 2015).

- 32. See, e.g. Bertil Bengtsson. “Reforming Swedish Sami legislation: A survey of arguments,” in Indigenous Rights in Scandinavia – Autonomous Sami Law, eds. Christina Allard and Susann Funderud Skogvang (Farnham: Ashgate, 2015).

- 33. E.g. CERD/C/SWE/CO/22-23 (June 6, 2018), “Concluding observations on the combined twenty-second and twenty-third periodic reports of Sweden”; A/HRC/33/42/Add.3, (August 9, 2016), Human Rights Council: “Report of the Special Rapporteur on the rights of indigenous peoples on the human rights situation of the Sami people in the Sápmi region of Norway, Sweden and Finland”; ACFC/OP/IV(2017)004 (June 22, 2017), Advisory Committee on the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities: “Fourth Opinion on Sweden”; CCPR/C/SWE/CO/7 (April 28, 2016), “Concluding observations on the seventh periodic report of Sweden”; E/C.12/SWE/CO/6 (July 14, 2016), Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. Concluding observations on the sixth periodic report of Sweden.

- 34. R. v. Sparrow [1990] 3 CNLR 160; R. v. Marshall; R. v. Bernard, 2005 SCC 43; R. v. Adams [1996] 4 CNLR 1.

- 35. In Swedish the estate is called Gällivare kronoöverloppsmark 2:1.

- 36. This boundary was interlinked with the partition in the north and initiated in 1867 when the Parliament decided that a preliminary cultivation boundary would be drawn up in the counties of Norr- and Västerbotten. See further Allard, “Two Sides of the Coin,” 336–37; SOU 2006:16 Samernas sedvanemarker: Betänkande av Gränsdragningskommissionen, 130–143.

- 37. In a Swedish civil law case, the court must adhere to the arguments and evidence presented by the parties and must not go beyond this legal framework.

- 38. Girjas v. the State, p. 4 and para 9. The Swedish State was represented by the Chancellor of Justice.

- 39. Girjas v. the State, paras 5–6.

- 40. E.g. s. 31 explicitly prohibits Sami to grant leases to others.

- 41. The Constitution: Instrument of Government, 1974, ch. 2 ss. 12 and 15.

- 42. ECHR Article 14 and Article 1 of the First Protocol.

- 43. Meaning that the State did not have the hunting and fishing rights that are normally part of the ownership and title to an estate.

- 44. Girjas v. the State, paras 8 and 10.

- 45. Girjas v. the State, paras 222–223. This was, following the Court, a procedural circumstance that they could not overrule.

- 46. These constitutional provisions have only been tried in the Skattefjäll case (1981) in relation to the leasing system, but since then there has been both an important amendment to the wording and a larger focus on constitutional matters in the Swedish courts. See further on this matter in the Skattefjäll case Allard, “Two Sides of the Coin,” 315–18.

- 47. Girjas v. the State, paras 87–124, and the dissenting opinion Appendix 1, paras 98–166.

- 48. Girjas v. the State, paras 123–124.

- 49. See Christina Allard and Malin Brännström, “Girjas sameby mot staten: En analys av Girjasdomen,” Svensk Juristtidning (2020): 446–48.

- 50. Girjas v. the State, para. 192.

- 51. Lapland is a traditional core Sami area and is still a designated, administrative area in northern Sweden. For a map see https://www.grundskoleboken.se/wiki/Lappland or https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lapland_(Sweden) (Accessed August 19, 2020).

- 52. Laura Carlson, The Fundamentals of Swedish Law (Lund: Studentlitteratur, 3rd ed., 2019), 131.

- 53. Another case, released a month before this case, also acknowledged the role of international law in this area. See the so-called Talma case, No. T 7463-18, decision 2019-12-20. This case was released by the Court of Appeal and here the Constitution and the ECHR were important for the outcome which favoured the Talma RHC. The issue was non-pecuniary damages regarding the infringements that the Swedish State made in the community’s reindeer herding right regarding the bi-lateral matter of transboundary reindeer herding in Norway. The State did not appeal this decision.

- 54. The Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention, 1989 (No. 169).

- 55. See, e.g. the public investigation SOU 1999:25.

- 56. Instrument of Government 1974:152, ch. 1 s. 2 para. 6. This section was amended with the general overhaul of the Swedish Constitution in 2010. Previously, the Sami were mentioned only as an ethnic minority; now they are referred to as a people within this written law. The Swedish Government declared that the amendment was an indication of the Sami’s special status as an Indigenous people within the State.

- 57. Girjas v. the State, para. 92.

- 58. Girjas v. the State, para. 93. The treaties mentioned here are: Council of Europe’s Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities (FCNM), in particular Article 5.1; UN’s International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESC): UN’s International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), in particular Article 1.2; and UN’s Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP).

- 59. Girjas v. the State, para. 94.

- 60. Girjas v. the State, paras 130–132.

- 61. “In applying national laws and regulations to the peoples concerned, due regard shall be had to their customs or customary laws.”

- 62. Girjas v. the State, para. 130.

- 63. UN’s Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, 2007.

- 64. UN’s International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, 1966.

- 65. Girjas v. the State, para. 131.

- 66. Girjas v. the State, para. 134.

- 67. Girjas v. the State, paras 161–7.

- 68. Roberth Nordh, “Bevisbörda och beviskrav i tvistemål,” Svensk Juristtidning (2012), 783. Burden of proof refers to which of the parties has the obligation to prove the statements of the claims made, and the evidentiary weight denotes how strong evidence must be to fulfil the onus of proof. While rules on burden of proof stem from general principles in several civil law situations, special rules may be established by legislation or by Supreme Court cases. See ibid., 783–4.

- 69. It has been argued, primarily in relation to country reports by human rights supervisory institutions, that the onus of proof should be reversed and placed on the other party. This would be more favourable to the Sami as an Indigenous people. See e.g. A/HRC/18/35/ Add.2 (June 6, 2011), “Report of the Special Rapporteur on the rights of indigenous peoples, James Anaya: The situation of the Sami people in the Sápmi region of Norway, Sweden and Finland,” paras 51, 82; CCPR/C/SWE/CO/6 (May 7, 2009), “Concluding observations of the Human Rights Committee: Sweden,” para. 21.

- 70. Girjas v. the State, para. 161.

- 71. Girjas v. the State, para. 161. For a discussion see Allard, “Two Sides of the Coin,” 223, 249, 273–4.

- 72. Girjas v. the State, para. 215. Here it is also explained that an established right also could be ceased voluntarily by the Sami community as right-holders.

- 73. See R. v. Sparrow [1990] 3 C.N.L.R: 160, 174–5.

- 74. Girjas v. the State, para. 162.

- 75. Girjas v. the State, para. 162.

- 76. Girjas v. the State, paras 162–3.

- 77. The Court exhorted caution in assessing the historical research on Lapland and the Sami from the twentieth century because it displayed significant disagreement regarding the Sami rights. See para.167 of the case.

- 78. Girjas v. the State, para. 164. The Court refers here to the Skattefjäll case (NJA 1981 p. 1) where the circumstances concerning the evaluation of evidence were similar.

- 79. Girjas v. the State, para. 166.

- 80. Girjas v. the State, para. 166.

- 81. The dissenting opinion applies only to the “issues of statutory interpretation”, i.e. paras 98–124.

- 82. This right exists notwithstanding the provisions in the Reindeer Herding Act ss. 31–34 that prohibit Sami from granting their rights to “outsiders”.

- 83. Girjas v. the State, para. 222.

- 84. NJA 2011 p. 109.

- 85. The issue at hand after the Nordmaling case was whether different concepts applied when claims regarding Sami reindeer herding rights were to be solved: immemorial prescription for mountainous areas (year-round pastures) and customary law for winter pasture areas. See Allard, “Nordmalingsmålet: Urminnes hävd överspelad för renskötselrätten?” Juridisk Tidskrift 1 (2011–12), 117–28; Bertil Bengtsson, “Nordmalingdomen – en kort kommentar,” Svensk Juristtidning (2011), 527–33.

- 86. Cf. here the role of custom in other areas of Swedish law. See Carlson, The Fundamentals of Swedish Law, 51.

- 87. In particular the Skattefjäll case, see Section 2.

- 88. Girjas v. the State, para. 133.

- 89. Although Swedish cases from the supreme courts are not formally binding for lower courts, in practice they are followed. Hence, Swedish law has no strict requirements of stare decisis and does not have the same need to “distingush the case” or to make sharp distinctions between ratio decidendi and obiter dictum. See Carlson, The Fundamentals of Swedish Law, 48.

- 90. These two main categories (year-round areas and winter pasture areas) are created by legislation. See Reindeer Herding Act of 1971, s. 3.

- 91. Girjas v. the State, paras 127–29, 133, here with reference to Christina Allard, Renskötselrätt i nordisk belysning (Stockholm: Makadam, 2015), Ch. 5.3.1.

- 92. Girjas v. the State, para. 133.

- 93. Ibid.

- 94. Girjas v. the State, para. 134.

- 95. The judgement implicitly shows that the Court recognises that rights based on customary law have traditionally been regarded as weaker rights, and the Supreme Court proves that it has a significant understanding of the historical and legal context. See further Allard, Renskötselrätt i nordisk belysning, 40–43, 46–47, 62–5, 69–70 and Ch. 3.4.

- 96. See further Allard, “Two Sides of the Coin,” 275–77.

- 97. Chapter 15 s. 1 of the Code is in old Swedish and states roughly: “It is immemorial prescription where someone has possessed, used and utilised real property or right in such long time undisputed and unhindered, that no one remembers or on good authority knows how his ancestors or auquirers came to be.”

- 98. Girjas v. the State, paras 152, 154.

- 99. Girjas v. the State, paras 137, 140–1. See further Allard, “Two Sides of the Coin,” 268–82.

- 100. Girjas v. the State, para. 147.

- 101. Girjas v. the State, para. 147.

- 102. Girjas v. the State, para. 149. Hunting and fishing has traditionally had a close connection to reindeer herding and the Court held therefore that the Nordmaling case, and the adjustments made by this Court, also had strong relevance for claims on Sami hunting and fishing.

- 103. There existed no clear conditions relating to customary law since it had not been applied in modern times.

- 104. Girjas v. the State, para. 205.

- 105. Girjas v. the State, para. 150.

- 106. Girjas v. the State, para. 151–2.

- 107. Girjas v. the State, para. 148.

- 108. See further Allard, Renskötselrätt i nordisk belysning, 270, 277.

- 109. Girjas v. the State, paras 154–6.

- 110. Girjas v. the State, paras 157–60.

- 111. See Girjas v. the State, paras 168–228.

- 112. Girjas v. the State, paras 168–71.

- 113. Girjas v. the State, para. 191.

- 114. Girjas v. the State, paras 197, 205.

- 115. Girjas v. the State, para. 205. See also at paras 189, 191, 227. Note that there was some evidence supporting that the Sami control was thwarted by Crown decisions, but on the whole competing land uses were limited (see paras 199–202).

- 116. Girjas v. the State, paras 163, 207.

- 117. Girjas v. the State, paras 203–4, 206.

- 118. Girjas v. the State, paras 215–7, 224.

- 119. Girjas v. the State, paras 213, 215–6, 224.

- 120. Girjas v. the State, paras 218–221, 225.

- 121. Girjas v. the State, paras 221, 225–6.

- 122. See “Högsta domstolens verksamhetsberättelse 2019,” (Stockholm: Supreme Court, 2019), 14. During 2019 when the case was prepared, the Supreme Court allocated about half of its resources to the Girjas case.

- 123. Girjas v. the State, para. 94. For instance, a broader interpretation is possible concerning the constitutional provision stating that preservation and development of Sami culture shall be promoted. See Section 4. However, it remains to be seen whether international law principles will mean a “strong” or “weak” interpretive principle in Sami cases. Cf. Maria Grahn-Farley, “Fördragskonform tolkning av MR-traktat”, Svensk juristtidning (2018): 450–63, 462–3. The Sami’s status as an Indigenous people may perhaps call for a strong interpretive principle.

- 124. See the discussion in Allard, Renskötselrätt i nordisk belysning, 40–3.

- 125. Girjas v. the State, para. 152. The Court calls the other form for “traditional immemorial prescription”.

- 126. Girjas v. the State, paras 161, 215.

- 127. This was not challenged by the Sami in 1956, and the responsible agency made no investigation on the matter of ownership.