1 Introduction

Canada continues to enter into treaties with Indigenous peoples. After a hiatus lasting several decades, the federal government re-engaged in treaty making in the wake of the 1973 Calder decision.1 Today, there are 26 “comprehensive land claims agreements”, or “modern treaties”2 as they are often called,3 that are being implemented across the country, with approximately 100 more under negotiation.4 Most of these modern treaties are in Canada’s three northern territories, although some exist in parts of Quebec, Labrador, and smaller areas of British Columbia.5

Unlike historical treaties in Canada, which were “typically expressed in lofty terms of high generality and were often ambiguous”,6 modern treaties are lengthy, sophisticated legal agreements that include chapters on heritage resources, land management, wildlife management, development assessment, land use planning, economic development, resource royalties, parks and protected areas, expropriation, and more.7 Modern treaties also include provisions for dealing with dispute resolution.8 While the treaties themselves resolve, or at least represent attempts to resolve, longstanding disputes between the Crown and Indigenous peoples about rights of land ownership and associated benefits, as well as governmental authority and jurisdiction, these agreements anticipate further disputes during the treaty implementation process. Typically, the dispute resolution provisions take the form of a stand-alone chapter setting out specific processes, institutions and jurisdiction for managing disputes.9

To date, the dispute resolution aspect of modern treaty implementation has received minimal scholarly attention, despite calls for such research,10 findings from the Office of the Auditor General regarding treaty implementation shortcomings,11 and litigation by Indigenous treaty parties.12 This article represents a modest first step in addressing this gap in the literature. It is primarily descriptive and explanatory in nature, setting a foundation for further research. Specifically, this article looks at the dispute resolution mechanisms of different treaties, commenting on key differences, similarities and other notable features. A core focus of the analysis is on the observable evolution in these provisions from a relatively narrow arbitration board model to a more flexible “staged approach”. The analysis presented in this article recognizes that dispute resolution between different cultures is inherently complex,13 and that such complexity is intensified by Crown-Indigenous relations in Canada that have been shaped by the extremely negative impacts of colonization and persistent power imbalances.14

The article proceeds as follows. Part II of this article sets out the legal and policy context within which modern treaties exist, including characterizations from the courts and broader policy changes. Part III describes the dispute resolution context in more detail, including in relation to alternative dispute resolution theory. Part III also discusses observable trends in the architecture of dispute resolution mechanisms and sets forth several examples from specific treaties that illustrate these trends.15 Part IV reflects on the content of and variation between dispute resolution mechanisms, putting forward several observations, including the tentative suggestion that the staged approach may provide a stronger basis for joint problem-solving and integrative bargaining, notwithstanding open questions about the extent to which such approaches are warranted in fraught Crown-Indigenous relationships in Canada. Several concluding points are offered at the end, drawing on the recognition that modern treaty dispute resolution processes are situated in a broader context of Indigenous treaty parties’ ongoing dissatisfaction with treaty implementation generally.16 The conclusion also puts forward starting points for further research.

Research presented in this article flows from the “Modern Treaty Dispute Resolution: Lessons & Prospects” research project, which is part of the “Modern Treaty Implementation Research Project” (MTIRP), a five-year Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) Partnership Grant secured by the Land Claims Agreements Coalition (LCAC).17 Further findings from this research project, including learnings from interviews with federal, territorial and Indigenous government officials, will be presented in a subsequent article. In today’s context of rapid federal law and policy change where many modern treaties are currently being negotiated and implemented,18 this research is timely and may contribute to treaty parties’ discussions on reforming dispute resolution processes.

2 Modern Treaties Background and Context

2.1 Modern treaties overview

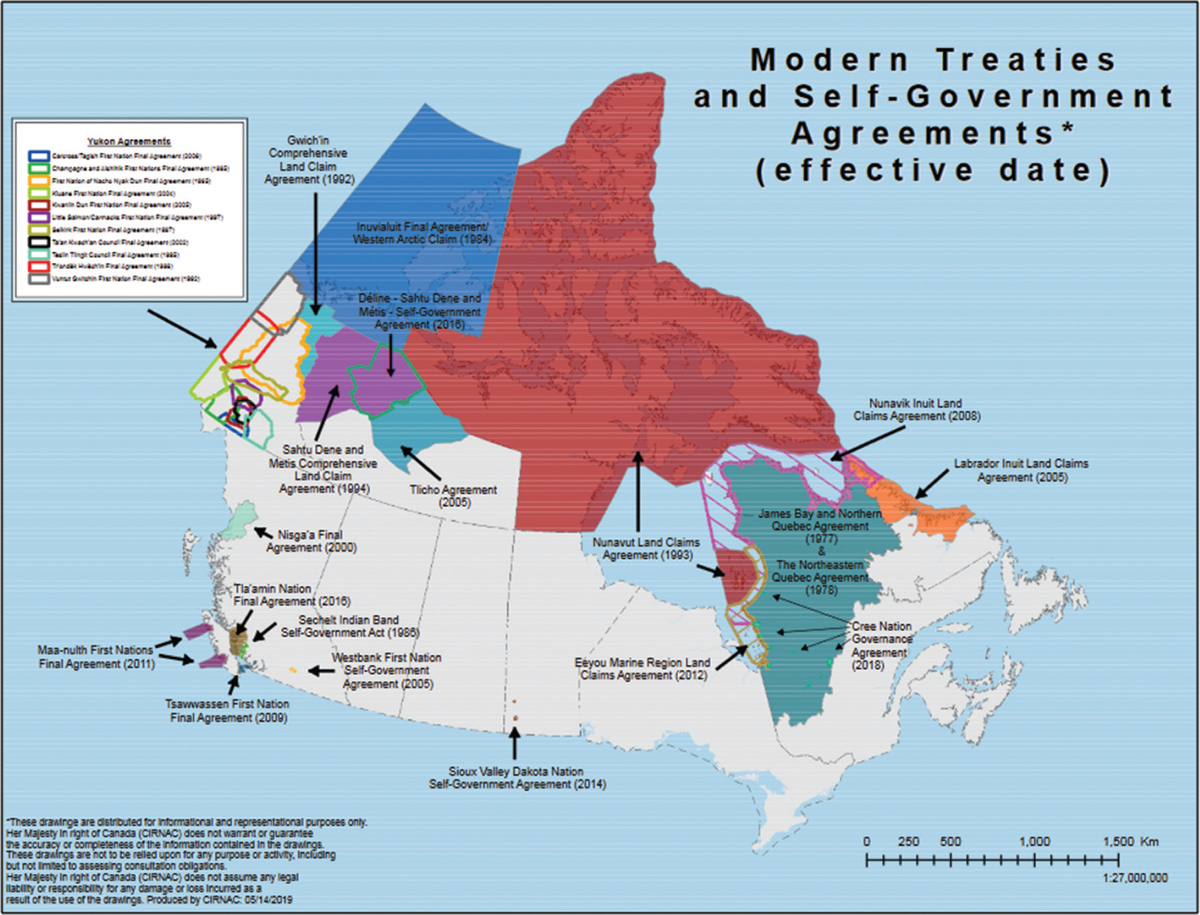

The modern treaty era flows from the 1973 Calder decision,19 wherein the Supreme Court acknowledged the existence of (but did not make a declaration of) Aboriginal title.20 Calder provided the legal footing for the first comprehensive land claims agreement negotiated between the Crown and First Nations, the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement of 1975.21 As indicated above, Canada and Indigenous communities have now concluded 26 such agreements, mostly in Canada’s three northern territories of Yukon, Northwest Territories and Nunavut. Collectively, modern treaties cover approximately 40 per cent of Canada’s land mass (see Figure 1). Virtually all of Canada’s Arctic region now falls within modern treaty boundaries.

These treaties are generally perceived as comprehensive legal agreements intended to clarify respective rights and interests in particular settlement areas.23 As described by Justice Binnie in Beckman v Little Salmon/Carmacks First Nation, modern treaties represent a “quantum leap” beyond historical treaties.24 They are the product of “lengthy negotiations between well-resourced and sophisticated parties”25. A key purpose of modern treaties, as stated by the Supreme Court of Canada, is “to foster a positive and mutually respectful long-term relationships between the signatories”,26 and these treaties “play a critical role in fostering reconciliation”.27

However, modern treaty implementation has not been a smooth process. Indigenous communities and governments approach land claims agreements from different perspectives. As Christopher Alcantara describes, “[i]n general, Aboriginal peoples want to maximize their control over their traditional lands to protect their traditional ways of life and practices, derive revenues and jobs from economic development, and take control of their lives in areas such as education, health, law enforcement, environmental protection, culture, heritage, fishing and hunting”.28 The federal government, meanwhile, is “primarily interested in ensuring certainty and finality for the purposes of encouraging economic development”.29 Perhaps owing to these different perspectives, courts and academics have pointed to several different analogies to characterize the legal personality of modern treaties, including as contracts, as constitutional accords, as agreements for sharing jurisdiction similar to federalism arrangements, and as covenants for shaping the relationship between the Crown and Indigenous peoples.30

It is in this context, with these different perspectives on the purpose and legal character of modern treaties, that disputes arise during treaty implementation. By including dispute resolution mechanisms within the treaties, as well as explicit consultation requirements,31 treaty parties clearly anticipated that disagreements would arise. For example, it was foreseeable that disputes might arise with respect to treaty interpretation (e.g. what rights and obligations actually flow from treaty provisions), treaty implementation (e.g. whether a treaty obligation has been fulfilled), third party dimensions (e.g. whether a party may access certain lands), and any combination of such issues in relation to specific treaty matters such as harvesting rights, economic development, water management, heritage resources, governance, and parks.

One way to resolve such disputes, of course, is through litigation. To date, Indigenous modern treaty parties’ litigation efforts have been largely successful;32 however, the Supreme Court has acknowledged that the courts’ role in resolving disputes in modern treaty implementation contexts ought to be circumscribed. While there is a role for the courts in adjudicating and then fashioning remedies, judicial restraint is also important, as articulated by J. Karakatsanis in First Nation of Nacho Nyak Dun v. Yukon:

[i]n a judicial review concerning the implementation of modern treaties, a court should simply assess whether the challenged decision is legal, rather than closely supervise the conduct of the parties at each stage of the treaty relationship. Reconciliation often demands judicial forbearance. Courts should generally leave space for the parties to govern together and work out their differences.33

…

[i]n resolving disputes that arise under modern treaties, courts should generally leave space for the parties to govern together and work out their differences. Indeed, reconciliation often demands judicial forbearance34

…

Judicial restraint leaves space for the parties to work out their understanding of a process — quite literally, to reconcile — without the court’s management of that process beyond what is necessary to resolve the specific dispute.35

Such an approach is consistent with the court’s affirmation that modern treaties are not a “complete code”.36 Rather, the experience of implementing modern treaties reinforces characterizations of treaties as “living agreements”.37 An important question in this context is whether dispute resolution mechanisms in modern treaties actually “leave space” and provide the tools needed by the parties to resolve disputes in ways other than litigation. As later sections of this article discuss, the extent to which modern treaties provide a basis – or “space” – for parties to resolve disputes varies widely.

2.2 Dispute resolution and modern treaties

Litigation presents challenges for all parties given its time and cost-intensive nature, as well as strains it may have on treaty party relationships.38 To some degree, these limitations resemble broader concerns with the conventional adversarial model based in western approaches to resolving disputes, namely, that it does not provide a forum that is sufficiently responsive to parties’ actual interests and needs.39 Instead, the adversarial nature of litigation confines dispute resolution within a positional paradigm that often leads to zero-sum exchanges of rigid offers and fails to find alternatives that satisfy the parties’ respective interests.40 These archetypal concerns with litigation have led to a significant expansion of mechanisms of “alternative dispute resolution” (ADR) since the 1970s.41 “Alternative” dispute resolution processes (i.e. alternative to a traditional litigation-based adversarial model) are thought to provide opportunities for parties to resolve conflicts in a form that achieves each party’s goals concurrently and efficiently.42 Proponents of ADR typically prescribe an “integrative” or “interest-based” approach within the ADR space, which involves disputing parties engaging with each other’s goals, priorities and preferences and then collaboratively exploring a range of settlement options.43

The appropriateness of different integrative dispute resolution methods in the Crown-Indigenous context in Canada is, however, a matter of debate. Professor David Kahane, for example, suggests that while ADR methods may appear to be a common-sense, universally applicable template for conflict resolution that can overcome cultural differences, these ADR methodologies may actually favour dominant cultural perspectives and systematically favour more powerful parties.44 He suggests a more nuanced approach to address complex dimensions of culture and power through building cultural sensitivity and incorporating diversity and representation into process design.45 Professor Michael Coyle acknowledges such complexities and critiques, but suggests that an integrative approach is preferable over the positional alternative, at least in contexts of undefined rights, because it at least provides a forum for “open discussion of the various ways by which such value concerns might be addressed”.46 He suggests that an integrative approach may be particularly helpful in an Indigenous governance negotiation context where there are more than two parties involved because it provides a process and space through which the parties can reach agreement on an ultimate outcome and then generate potential options that are sensitive to an Indigenous party’s interests and traditional values.47 Coyle goes on to suggest that, “where Aboriginal groups have decided to engage with the state, adopting an integrative approach appears to be a wise response to the potential impacts of power imbalance”.48

Relating this to today’s modern treaty context, there are substantial differences in the degree to which treaties provide a basis for addressing ongoing power imbalances and cross-cultural complexities through an integrative approach. This is a product of the significant variance across dispute resolution mechanisms present in different treaties, as detailed in the next section. Overall, while resolution of disputes through litigation is often available,49 the available mechanisms for non-litigation dispute resolution in existing modern treaties vary widely, with different latitude for parties to engage in less adversarial processes such as direct negotiation or mediation.

As discussed below, modern treaty parties formally agreed to specific mechanisms as part of their treaty; however, the rationales for those mechanisms have become, in most cases, frustrated or forgotten by practices and experience that have made them inaccessible. The extent to which these dispute resolution mechanisms were carefully designed and calibrated to navigate cultural and power dynamics inherent in the Crown-Indigenous context is not clear. Today, in some cases several decades after finalizing treaty text, and with federal willingness to “modernize” the earliest agreements, it is reasonable to expect that parties may be interested in revisiting dispute resolution options in the future. Such revisiting could steer toward greater inclusion of non-adversarial processes that may be suited for addressing power imbalances and cultural differences as a way to build stronger treaty relationships. This article and the associated research project described above are intended to be a modest contribution to discussions in this reform sphere.

2.3 Evolving federal law and policy context

Before moving on to discuss different dispute resolution mechanisms in existing modern treaties, it is important to acknowledge that dispute resolution in modern treaty contexts exists in a broader law and policy environment that is changing relatively quickly. The last several years have been a particularly intense period of announcements and changes at the federal level. In 2015, for example, the federal government put in place the Cabinet Directive on the Federal Approach to Modern Treaty Implementation50 and released the Statement of Principles on the Federal Approach to Modern Treaty Implementation.51 The former sets out the federal government’s “operational framework for the management of the Crown’s modern treaty obligations” and “guides federal departments and agencies to fulfill their responsibilities”.52 In addition to setting out departmental roles, it includes several specific requirements, including an obligation on all departments and agencies to consider modern treaty implications when developing policy, plan and program proposals to submit to Cabinet. It also created the Deputy Ministers’ Oversight Committee “to provide executive oversight of the implementation of the Directive, and by extension, of Canada’s roles and responsibilities under modern treaties”.53 Finally, it created the Modern Treaty Implementation Office (MTIO) to “provide ongoing coordination and oversight of Canada’s modern treaty obligations, and to support the mandate of the Deputy Ministers’ Oversight Committee”.

A number of other high-level law and policy changes have emerged since the 2015 federal election. Notable developments include the federal government’s “full support” of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) without qualification,54 the federal “Review of Laws and Policies Related to Indigenous Peoples”,55 announcement of a new “recognition and implementation of rights framework”,56 the “Principles respecting the Government of Canada’s relationship with Indigenous peoples”57 (typically referred to as the “10 principles”), adoption of a new “Directive on Civil Litigation Involving Indigenous Peoples”,58 and ongoing work to implement the Truth and Reconciliation Commissions Calls to Action. While these developments are not specifically targeted at modern treaty implementation, they illustrate the relatively rapid pace of law and policy change in recent years and may have implementation implications. These changes can be viewed in at least two ways. Some might view these as setting the stage for the federal government to follow through on the “renewed nation-to-nation relationships” it has emphasized in recent years, including in mandate letters to Ministers.59 However, one might take a more critical view that these changes and announcements fall short of concrete action that addresses the actual interests and priorities of Indigenous communities.

Whatever perspective one adopts with respect to these recent developments, there are some indications that they are having an impact on modern treaty implementation. For example, in the 2018 budget process, Canada changed the funding model away from loans, forgave the accumulated debts of groups currently in negotiations, and pledged to reimburse Indigenous parties for the costs of modern treaty negotiations.60 Canada has also updated its collaborative self-government fiscal policy to “provide a principled approach to fiscal relations with all Indigenous Governments in a manner that is consistent with the commitments made in self-government agreements and modern treaties”.61 Additionally, the federal government has worked with some modern treaty parties to establish “treaty modernization tables” to discuss and possibly address (in some cases, through treaty amendments) parties’ concerns with existing modern treaties, including dispute resolution provisions.62 The observations in this article, and in forthcoming articles from the above-mentioned modern treaty implementation research project, may assist modern treaty parties in modernization discussions. In Canada today, the policy stage appears to be set for changes in dispute resolution in modern treaty contexts. A key initial step is to understand current mechanisms and arrangements, which the following section discusses.

3 Dispute Resolution Mechanisms in Modern Treaties

3.1 Overview of existing dispute resolution mechanisms

There is significant variance in the dispute resolution mechanisms found in modern treaties across Canada. It is possible, however, to discern two main approaches: a relatively narrow arbitration committee/board structure to resolve disputes, and a broader “staged approach”. All of the 26 agreements currently being implemented contain one of these two models, or, as discussed in more detail below, a mix of them. Generally, most agreements finalized before 1999 use the arbitration committee/board approach model, and most finalized after 1999 use the staged approach; however, there are significant differences across agreements and limited understanding as to why such variance exists.63 The following discussion offers brief descriptions of these two models and then presents several examples of each, with particular attention to the Gwich’in, Tłı̨chǫ, Nisga’a, Nunavut, Yukon and Inuvialuit agreements.64

3.1.1 Arbitration board approach (pre-1999)

Although there are textual differences across agreements, for the most part agreements using the arbitration board model follow a common format of establishing an arbitration board and then setting out details regarding board/panel composition, board member term length, roles and duties of the board, jurisdictional parameters (i.e. what issues the board may hear), funding responsibilities (typically shared by parties), selection and number of arbitrators for specific disputes, and procedural dimensions (e.g. how to initiate the arbitration process).

Under this model, the arbitration board is essentially an oversight body that administers the dispute resolution process. The parties either select an arbitrator from the larger board (or panel or roster), or the parties individually or jointly select a group of three arbitrators according to the terms of the treaty, to resolve specific disputes as they arise. Typically, in this type of modern treaty dispute resolution model there is no formal requirement for parties to first attempt to resolve the dispute through dialogue, negotiation or mediation, though treaty provisions do not preclude such steps. Examples of the board approach can be seen in the Inuvialuit and Gwich’in final agreements, and in the original Nunavut Agreement dispute resolution chapter, which are described below and included in the summary table at the end of Part II.

3.1.2 Staged approach (post-1999)

Most post-1999 agreements use the staged approach in the dispute resolution chapters, though the 1992 Yukon Umbrella Final Agreement (UFA) takes a staged approach and is therefore an exception to the pre-1999 time period. The staged approach emphasizes resolving disputes relatively informally before escalating the dispute to more formal channels. When issues arise, parties are to go through each stage before progressing to the next. The staged approach to resolving disputes typically progresses as follows. Stage one calls for informal discussion and direct negotiation wherein officials of each party meet to express and attempt to resolve concerns and disputes. Stage Two contemplates more formal negotiations, including mediation. In this stage, issues not resolved at the informal discussion level proceed to a facilitated process involving a neutral third party who helps resolve issues in a non-binding manner. Most modern treaties with this process set out the steps and timeframes for this stage, including how parties submit notice of entering into the process, how the neutral third party is chosen, how long the assisted negotiation/mediation will take place, and what to do in the event the dispute is resolved, or remains unresolved. The final stage is arbitration. This stage is invoked when the dispute has not been resolved in the lower stages. Agreements vary as to whether all parties must agree to invoke the arbitration process (discussed in more detail below). The arbitration process typically issues a binding decision on a set timeline.

Examples of the staged approach exist in the Nisga’a and Tłı̨chǫ final agreements, as well as the new dispute resolution chapter for the Nunavut Agreement. These are described in the next section below, which offers a summary of key structures, approaches and institutions in several modern treaties.

3.2 Specific modern treaty examples

3.2.1 Inuvialuit Final Agreement (1984)

The Inuvialuit Final Agreement (IFA) was finalized in 1984, representing just the second comprehensive land claim agreement in the modern treaty-making era. Dispute resolution in Chapter 18 of the Inuvialuit Final Agreement is an example of the arbitration board model. This chapter features perhaps the broadest scope of any of the modern treaty dispute resolution mechanisms, primarily by virtue of article 18(16):

18. (16) Except as otherwise provided by this Agreement, Canada, the Inuvialuit or Industry may initiate arbitration by giving notice to the other party to the dispute and a copy to the Chairman of the Arbitration Board for circulation to all members of the Board. Where a matter for arbitration is within the jurisdiction of the Government of the Northwest Territories or Yukon Territory, Canada agrees to initiate arbitration on request by the Territorial Government.65

Under this provision, both the Inuvialuit and Canada have unilateral power to refer a matter to arbitration. This stands in contrast to other agreements, such as the Gwich’in Comprehensive Land Claim Agreement (GCLCA), where in many cases the parties must agree to go to arbitration, which effectively provides a veto to each party. Arbitration may also be initiated by Industry, a feature that is not common to other modern treaties. Further, so long as the matter for arbitration is within the jurisdiction of the GNWT or Yukon Government, Canada must initiate arbitration if so requested by one of the territorial governments. Finally, s.18(17) widens the scope further by allowing any party to intervene if its interests are affected.66

The arbitration board’s jurisdiction is very broad. Section 18(33) states: “The Arbitration Board shall have jurisdiction to arbitrate any difference between the Inuvialuit and Industry or Canada as to the meaning, interpretation, application or implementation of this Agreement”.67 As such, there are virtually no constraints on what disputes between the Inuvialuit, Canada and Industry the board may hear.68 Additionally, jurisdiction is also granted to the board over specific issues that may involve third parties or beneficiaries such as enrolment,69 certain land matters,70 expropriation,71 participation agreements,72 and wildlife compensation awards, recommendations and decisions.73 Referral to the arbitration board is also explicitly referenced in other IFA chapters. For example, article 7(12) provides that in the event that Canada and the Inuvialuit fail to negotiate a work program in relation to exploration or production of “respective resources”, either party may refer the matter to the arbitration board.74 With respect to litigation, the IFA includes no explicit bar to any party commencing a lawsuit at any point; however, several specific types of disputes contemplated in other chapters of the agreement require referral to the arbitration board if agreement cannot be reached.75

In terms of composition, the IFA requires that the board have 11 members, including a chairperson and vice-chairperson.76 Five members are to be appointed by Canada, of whom two are a chairperson and vice-chairperson found “acceptable to the Inuvialuit and Industry” and two are designated by the territorial governments, respectively.77 The Inuvialuit and Industry78 must each appoint three other members to the board.79 In an arbitration where the interested parties are only the Inuvialuit, Industry and Canada, the panel would consist of just seven members.80 Similar to the GCLCA, but unlike other agreements, the IFA does not establish any kind of supporting institution or formal administrator. The IFA explicitly indicates that decisions of the board are reviewable by the Federal Court of Appeal.81 Over the years, this arbitration board has been active from time to time, including for example, disputes pertaining to government contracting and royalties.82

3.2.2 Gwich’in Comprehensive Land Claim Agreement (1992)

Dispute resolution in the Gwich’in Agreement is an example of the arbitration board model.83 Jurisdiction of the arbitration panel is set out in article 6.1.5 of the GCLCA:

The panel described in 6.2 shall have jurisdiction to arbitrate in respect of:

(a) any matter which this agreement stipulates is to be determined by arbitration; and

(b) any matter concerning the interpretation or application of this agreement where the parties agree to be bound by an arbitration decision in accordance with this chapter.

Under this regime there are two routes to arbitration: either as prescribed by a specific governing provision elsewhere in the Agreement, or by agreement between the parties. Under the former, there is variation between specific provisions. For example, article 20.3.1, dealing with government access to Gwich’in lands, creates an automatic requirement to proceed to arbitration if government and the Gwich’in Tribal Council cannot reach a negotiated agreement,84 whereas article 20.1.7, dealing with certain circumstances of public or commercial access to Gwich’in lands, provides authority to the Gwich’in Tribal Council or government to refer the matter to arbitration.85

The other route is under subsection 6.1.5(b), where jurisdiction of the arbitration panel hinges on whether “the parties agree” to refer the matter to the panel and be bound by the panel’s decision. This latter route effectively provides each party with a veto over any other parties’ desire to engage the treaty’s dispute resolution mechanism. This is similar to the original Nunavut Land Claim Agreement (NLCA) provisions discussed below.

Unlike other modern treaties such as the Nisga’a Final Agreement, the dispute resolution chapter in the GCLCA does not set out any detail regarding, nor explicitly require, other dispute resolution methods before proceeding to arbitration. However, Chapter 6 clearly implicitly acknowledges (but does not stipulate) that negotiation will take place prior to advancing to arbitration, stating that, “[t]he provisions of this chapter apply to any dispute which is not resolved by discussion and negotiation”.86 Additionally, a number of provisions suggest parties should first attempt to achieve a negotiated solution. For example, provisions in other chapters that explicitly reference referral to the arbitration panel indicate that such referral is to take place if an agreement cannot be reached through negotiation.87 Further acknowledgement that disputes may be resolved through means other than the arbitration panel can be found in 6.1.7, which indicates that nothing in the chapter prevents parties from “agreeing to refer it to an alternate dispute resolution mechanism such as mediation or arbitration”.88 In this way, the treaty clearly does not preclude use of different dispute resolution approaches, and instead implicitly provides a basis for such practices without a requirement to do so. With respect to litigation, the GCLCA includes no explicit bar to any party commencing a lawsuit at any point, although the provisions that require commencement of arbitration imply that this step is first required.89

The GCLCA also acknowledges a role for the Implementation Committee in resolving disputes.90 Article 28.2.3 states that, “[t]he Implementation Committee shall operate on a consensus basis and shall: … (d) attempt to resolve implementation disputes arising between the parties. Unresolved implementation disputes shall be resolved pursuant to arbitration under chapter 6”.91

In terms of composition, the GCLCA requires that an arbitration panel be established92 and that it be comprised of eight members, including a chairperson and vice-chairperson,93 and individuals appointed by Canada, the GNWT and the Gwich’in Tribal Council respectively.94 Institutionally, unlike other modern treaty regimes, the GCLCA does not establish any kind of supporting institution or official position. One risk that exists in relation to the dispute resolution structure in these agreements is that the arbitration boards are not sufficiently populated by the parties, resulting in the panels being unable to function (i.e. the parties do not make appointments in a timely manner, or disagreements over appointments hinder appointments). Perhaps related to this circumstance, there is no publicly available example of the GCLCA arbitration mechanism ever being invoked.

In a narrow set of specific circumstances, the GCLCA also provides dispute resolution authority to bodies other than the arbitration panel. For example, the Surface Rights Board determines compensation in situations where approved access to Gwich’in lands results in damage or interference and the Gwich’in Tribal Council and the other party are unable to agree on compensation.95 Similarly, the Land and Water Board determines compensation in contexts where the Gwich’in Tribal Council and the other parties are unable to agree on compensation to be paid to Gwich’in in relation to water rights.96 And the Supreme Court of the Northwest Territories hears any individual’s appeal regarding enrolment under the GCLCA.97 The GCLCA also provides for the arbitration regime under the National Energy Board Act to apply in contexts of expropriation under that Act.98 In terms of judicial review, article 6.1.2 makes clear that the Supreme Court of the NWT has jurisdiction over any action arising out of the GCLCA, and article 6.1.3 states that decisions by an arbitration panel are reviewable by the Supreme Court of NWT99 but only on grounds that the arbitrator(s) erred in law or exceeded jurisdiction.100

3.2.3 Yukon Umbrella Final Agreement (1993)

Dispute resolution under the 19932 UFA101 is structured as a staged approach despite being finalized prior to the post-1999 shift to inclusion of stages in most modern treaties. The UFA provides a basis for parties to first go to mediation. Articles 26.3.5 (“specific disputes”) and 26.4.3 (“other disputes”) indicate that if a dispute is not resolved by mediation, parties may agree to then refer it to arbitration. These provisions do not explicitly require parties to engage in mediation prior to initiating arbitration.

The UFA is structured around “specific disputes” and “other disputes”. In short, matters that constitute “specific disputes” and “other disputes” are substantially similar (e.g. both include matters that the UFA explicitly refers to dispute resolution), but the dispute resolution avenues and options are slightly different. For “specific disputes”, there are two main ways for the dispute resolution process to be engaged. First, any party may refer the matter to mediation if it is a matter that the UFA or a Settlement Agreement explicitly refer to the dispute resolution process.102 Second, matters not explicitly referred under the UFA or an Agreement, whether related to a Settlement Agreement or not, may be referred to the dispute resolution process if all parties agree.103

For “other disputes”, similar to specific disputes, any party may refer the matter to mediation if it is a matter that the UFA or a Settlement Agreement explicitly refers to the dispute resolution process. Additional disputes may also be referred to mediation if all parties agree.104 Further, a party may refer a dispute (and an “other dispute” but not a “specific dispute”) to mediation if that matter is directed to dispute resolution by a board established under a Settlement Agreement.105 Similarly, there is broad scope provided by 26.4.1.5 whereby “any matter arising out of the interpretation, administration, or implementation” of a Settlement Agreement may be referred to mediation “with the consent of all the other parties to that Settlement Agreement”.106

The mediation process is the same for specific disputes and other disputes. It is set out in 26.6.0, including timelines, appointment of a mediator, recommendations of the mediator, costs, and confidentiality. If a specific dispute is not resolved through mediation, any party may refer the dispute to arbitration.107 By contrast, any “other dispute” requires agreement between the parties to refer the matter to arbitration.108

Arbitration is available to parties without first having to exhaust the mediation stage. However, for disputes referred to mediation, this stage must be exhausted before the matter may then be referred to arbitration. For specific disputes, any party may make this referral.109 For other disputes, agreement of the parties is required.110 The arbitration process is the same for specific and other disputes, as set out in 26.7.0, including timelines, appointment of an arbitrator, authorities of the arbitrator (e.g. administering oaths, subpoenaing witnesses, etc.), costs, and the binding nature of decisions.

The above-described channels to mediation and arbitration in the UFA are reinforced by provisions that explicitly preclude litigation. Unlike the Gwich’in and Inuvialuit contexts, under the UFA parties are barred from commencing litigation in some situations. For example, no party may apply to a court for relief if the matter could be referred to mediation as a specific dispute,111 and no party may apply to a court for relief if the dispute has been referred to arbitration following mediation.112 Institutionally, Chapter 26 requires the establishment of a Dispute Resolution Board comprised of three individuals. One member is appointed by Yukon First Nations, one by Canada and the Yukon, and the third is appointed jointly. The Board’s roles and responsibilities are set out in 26.5.4. The primary function of the Board is to support and administer the dispute resolution process, including maintaining a roster of arbitrators and mediators, appointing arbitrators and mediators, and establishing mediation and arbitration rules and procedures.113

The UFA also acknowledges a role for an “Implementation Planning Working Group” comprised of one representative appointed by Canada, one representative appointed by the Yukon, and two Yukon First Nation representatives.114 Under 28.4.5, the UFA anticipates that this working group will work to reach agreement on any particular issue, but if the working group is unable to reach agreement then it must be referred to the parties.115 This resembles the role described above in relation to Implementation Committees under the GCLCA.

Decisions of an arbitrator are reviewable by the Supreme Court of the Yukon116 but only on grounds that “the arbitrator failed to observe a principle of natural justice or otherwise acted beyond or refused to exercise jurisdiction”.117

3.2.4 Nisga’a Final Agreement (1999)

Dispute resolution under the Nisga’a Final Agreement (NFA) is an example of a staged approach, wherein the parties must follow the requirements of a stage prior to escalating to the next stage unless the parties agree otherwise. Chapter 19 of the NFA and a series of related appendixes118 comprise the most lengthy and detailed dispute resolution provisions of all modern treaties. These mechanisms have been used by parties from time to time, including in disputes pertaining to environmental assessments,119 and land access.120

The opening provisions of Chapter 19 set out shared objectives to prevent, minimize and resolve disagreements in a relatively informal and cooperative manner that does not require engagement of the formal dispute resolution stages. For those disputes that are not resolved in such an informal manner and which fall within the broad description of conflicts and disputes in s.7 (e.g. disputes regarding interpretation, application, implementation or breach of the Agreement),121 parties must address their disputes by going through three specific stages set out in s.12:

(a) Stage One: formal, unassisted efforts to reach agreement between or among the Parties, in collaborative negotiations under Appendix M-1;

(b) Stage Two: structured efforts to reach agreement between or among the Parties with the assistance of a neutral, who has no authority to resolve the dispute, in a facilitated process under Appendix M-2, M-3, M-4, or M-5 as applicable; and

(c) Stage Three: final adjudication in arbitral proceedings under Appendix M-6, or in judicial proceedings.

Details of each step are set out in ensuing provisions. For example, sections 20–27 set out details regarding the stage two “facilitated processes”, including timelines, notice, termination, a more detailed referencing of the relevant appendixes, and a description of mandatory “negotiation conditions” such as timely disclosure and good faith. Similarly, stage three arbitration details are set out in section 28–34, including reference to the relevant appendix. There are two routes to arbitration set out in sections 28 and 29. For disagreements arising out of an NFA provision that stipulates that the matter will be “finally determined by arbitration” the disagreement automatically proceeds to arbitration after the other two stages are exhausted. For all other disputes, arbitration is still available, but only with written agreement from all parties.122

A feature that makes the NFA stand out against other modern treaties is the inclusion of a relatively large number of process options, which are detailed in appendixes M-1 – M-6. These are as follows: collaborative negotiations in M-1, mediation in M-2, technical advisory panel in M-3, neutral evaluation in M-4, Elders Advisory Council in M-5, and arbitration in M-6.123 These comprise a significant suite of process options not explicitly present in other modern treaties, and the Elders Advisory Council is unique in the modern treaty realm. However, agreement between all parties is required to use any facilitated process other than mediation.124 This means, for example, that referring a dispute to the elders advisory council is subject to a veto by the government.

Stage three also provides for parties to commence judicial proceedings instead of arbitration. However, a party may not commence litigation if the NFA explicitly requires it to be determined by arbitration, or if parties have already agreed to refer it to arbitration, or if stages one and two have not been completed.125

Unlike the UFA or Tłı̨chǫ contexts, the NFA does not establish any standing institutional body or support structure. Rather, each appendix dictates the process, composition and rules pertaining to each dispute resolution mechanism. For example, Appendix M-5 deals with the Elders Advisory Council, setting out details regarding appointments, procedure, confidentiality, decision-making and termination. Appendix M-6 sets out similar for the arbitration process, though it includes a great deal of detail.126 Under the NFA Appendix M-6, arbitration decisions are reviewable by the Supreme Court of British Columbia, and parties may request that court to make a ruling on a question of law.127

3.2.5 Tłı̨chǫ Final Agreement (2003)

Dispute resolution under Chapter 6 of the Tłı̨chǫ agreement is an example of the staged approach. In general, the Agreement requires that parties first attempt to resolve disputes through discussions, then mediation, then arbitration. Each stage must be exhausted before the dispute may escalate to the next stage, and a party may only take a dispute to court if the first two stages fail to resolve the dispute.128 For example, mediation is only available if parties have “attempted to resolve that dispute by discussion”.129 Notably, each party has the ability to refer a dispute to mediation if discussions have not resolved a dispute. This means that no party possesses veto power over another party’s attempt to refer a dispute to mediation.130 However, these similar powers are more circumscribed for arbitration, which requires agreement by the parties,131 and arbitration is only available after the mediation stage.132 As a dispute proceeds through the stages, however, the parties may resolve their dispute by an agreement in writing.133

The scope of disputes that may be referred to dispute resolution is very broad, similar to that of the IFA described above. Article 6.1.1 provides that the dispute resolution mechanisms are available in relation to any “dispute between the government and the Tłı̨chǫ government concerning the interpretation or application of the Agreement”, and to any matter that the Agreement refers to the dispute resolution process, and to any matter which an agreement between the parties stipulates may be resolved through the Chapter 6 mechanisms.134 However, for disputes that proceed beyond mediation, the avenue to arbitration is narrowed. While arbitration may be used with respect to a broad scope of disputes that pertain to “interpretation or application of the Agreement”, the arbitration process is only available if “the parties to the dispute agree in writing to be bound” by the arbitration decision, or if the dispute is explicitly referred to arbitration under the Agreement or as stipulated by another between the parties.135

Institutionally, the dispute resolution mechanisms under the Tłı̨chǫ Agreement are supported by a “dispute resolution administrator” who is jointly appointed by the Tłı̨chǫ Government, Canada and the GNWT.136 It is this administrator’s role to oversee mediation and arbitration processes, including establishing and maintaining a roster of mediators and arbitrators, establishing rules of procedure, appointing mediators and arbitrators, and maintaining records.137 In a small set of circumstances (land access under Chapter 19), a dispute must be referred to the Surface Rights Board instead of the administrator.138 Similarly, the Wekeezhii Land and Water Board has jurisdiction over a small set of disputes,139 and disputes regarding compensation for lands expropriated under the National Energy Board Act would be heard by an arbitration committee under that statute.140

Questions of law may be referred to the Supreme Court of NWT by the administrator,141 and a decision of an arbitrator is considered conclusive and binding but may be challenged on grounds that the arbitrator(s) erred in law or exceeded jurisdiction.142

3.2.6 Nunavut Land Claims Agreement (1993/2017)

The original version of the Nunavut Land Claims Agreement (NLCA or Nunavut Agreement)) featured the arbitration board approach,143 specifically requiring agreement from the parties to commence arbitration.144 This became a significant barrier in the Nunavut context when Canada used its veto power in 17 instances where it responded to NTI’s dispute resolution requests with a refusal to proceed to arbitration.145 Ensuing litigation (there was no explicit bar to litigation in the original agreement), including a summary judgement and appeal decision,146 led to a settlement agreement in 2015 that included a commitment to amending the dispute resolution provisions in the NLCA.147 Under the revised Chapter 38, dispute resolution now follows the staged approach. Though a relatively recent development, these new mechanisms have already been invoked in two circumstances, one dealing with government employment148 and another dealing with government contracting.149

The revised dispute resolution chapter in the Nunavut Agreement features four stages: informal processes, negotiations at the implementation panel, mediation, and arbitration.150 The revised process requires that parties first attempt to resolve disputes through “informal processes”, then through the Implementation Panel,151 then mediation,152 then arbitration. With the exception of a small set of circumstances described below in relation to arbitration, each stage must be exhausted before the dispute may escalate to the next stage. For example, mediation is only available “60 days after the date of the Implementation Panel meeting during which the dispute was first discussed”.153 For all stages, any party may refer the dispute to the next stage so long as procedural dimensions such as notice and time periods are satisfied. Parties are not precluded from turning litigation at any point, as article 38.7.4 indicates that ‘[e]xcept in respect of disputes arbitrated under these provisions, nothing in these provisions affects the jurisdiction of any court”.154

With respect to arbitration under 38.5, any party may refer several specific types of matters to arbitration without having to exhaust the previous stages (e.g. mediation) – these include disagreements regarding the incompatibility of harvesting activities with authorized land use (5.7.19), access across Inuit Owned Lands for commercial purposes (21.7.15), compensation for expropriation (21.9.8), and proposals for long-term alienation of archeological specimens.155 All other disputes may only proceed to arbitration if mediation does not first resolve the dispute.156

The scope of disputes that may proceed through these stages is relatively broad, including disputes between two or more parties involved (Canada, the Government of Nunavut and the Designated Inuit Organization(s)) regarding the “interpretation, application or implementation of the Agreement”, or disputes specifically referred to dispute resolution by other provisions in the Agreement.157 Surrounding the entire revised dispute resolution regime, there are soft commitments in article 38.2 to “settle disputes informally through cooperation” and to “engage litigation only as a last resort”.158

Questions of law may be referred to the Nunavut Court of Justice,159 and any party may appeal the arbitration award to the Nunavut Court of Justice.160 Other than the Implementation Panel, no devoted institutions or administrative bodies are created under the revised Chapter 38. In this way, the new Nunavut regime differs from the Tłı̨chǫ regime and Yukon regime described above.

| Treaty | DR Model | How to refer to dispute resolution | Non-arbitration stages available? | Non-arbitration stages required? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gwich’in (1992) | Arbitration Board | Agreement/consent required from all parties | Yes, informally | No |

| Inuvialuit (1984) | Arbitration Board | Any party may refer (and industry may also) | Yes, informally | No |

| Yukon UFA (1993) | Staged | Mixed – some disputes require agreement/consent | Yes | No |

| Nisga’a (1999) | Staged | Any party may refer | Yes | Yes |

| Tłı̨chǫ (2003) | Staged | Mixed – any party for mediation; agreement required for arbitration | Yes | Yes |

| Nunavut (old – 1993) | Arbitration Board | Agreement/consent required from all parties | Yes, informally | No |

| Nunavut (amended – 2017) | Staged | Any party may refer | Yes | Yes (but some can be referred to Arb without lower steps) |

4 Observations and Commentary

This review of modern treaty dispute resolution mechanisms and associated context leads to several observations. First, and speaking at a high level, there are significant differences across modern treaty dispute resolution chapters. This can be seen in the basic architecture, as described at the beginning of this section (i.e. staged vs. arbitration board approach), as well as in specific features such as parties’ veto power, parties’ flexibility in choosing dispute resolution forums (including barriers to litigation before early stages are complete), appointment processes, judicial review, formal timelines, and institutional dimensions. This can also be seen in the significant variance in the level of detail in the dispute resolution chapters of different treaties. At either end of the spectrum are the Nisga’a Agreement, which contains a significant level of specificity through the chapter and six appendixes,161 and the IFA, which occupies just two pages focused entirely on arbitration.162 The basis for such differences is not clear.163

Second, there has been a discernable shift over time from the arbitration board model to the staged approach. Where the board approach was common in earlier treaties such as the Inuvialuit or Gwich’in agreements, and the staged approach is the dominant approach in more recent agreements.164 Notably, however, the UFA included stages in an agreement that was finalized around the same time as the Nunavut and Gwich’in agreements, and the Nisga’a Agreement included details and mechanisms, such as a role for an elders advisory council, that have yet to appear in subsequent treaties. Accompanying this evolution in general structure is a move away from providing any single party with the power to refuse to refer a matter to dispute resolution. This evolution is observable in the amended Chapter 38 of the Nunavut Agreement described above. Similar to the above observation, the basis for this evolution and shift is not completely clear, though a statement of preference by the federal government for the staged approach can be seen in Canada’s “Guide for the Management of Dispute Resolution Mechanisms in Modern Treaties”.165 Overall, finer points of the trend line in this evolution are not entirely crisp and significant differences exist even within more recent treaties.

Third, treaties vary with respect to how softer measures and language around spirit and intent are included (or not) and articulated (or not) within dispute resolution chapters. The new Nunavut chapter, for example, recites several “general principles” that emphasize good faith efforts and avoiding litigation, whereas the Gwich’in and Inuvialuit agreements contain virtually no such language.

Fourth, none of the treaties discussed above include an explicit basis for dispute resolution approaches rooted in traditional or cultural practices of Indigenous parties. The closest example of such can be seen in the Nisga’a Agreement’s inclusion of an elders advisory council as a potential dispute resolution body under stage two of that process.166 While such alternative approaches may well be possible under different modern treaties by agreement of all parties,167 there is no formal basis for this. To the extent that one views dispute resolution in modern treaties as an opportunity for revitalization of Indigenous laws and governance, this omission can be seen as a significant gap.168 A caveat to such a conclusion in many specific treaty contexts, however, is the “co-management” nature of the boards and appointment processes.169 That is, Indigenous parties’ direct participation and representation in the structures and processes (e.g. arbitration boards require Indigenous appointees by Indigenous treaty parties and mediation typically requires joint appointment of mediators) could be seen as a basis for the integration of Indigenous perspectives, including traditional perspectives and practices.

Fifth, the role of the implementation committee (or implementation panel or implementation working group, as it may be called) differs under the treaties. The Nisga’a Agreement, for example, includes no reference to such a body in relation to dispute resolution, whereas the Gwich’in and Yukon agreements, and the amended Nunavut Agreement, all explicitly (though differently) envision a role for these bodies in resolving matters early in the dispute resolution process.

Sixth, and related to the above point, there are significant differences across treaties at the institutional level. While some agreements require establishment of administrative bodies or offices, such as the Yukon Dispute Resolution Board in Yukon and the Dispute Resolution Administrator under the Tłı̨chǫ Agreement, other agreements, including the amended Nunavut chapter, contain no such requirements.

Finally, reflecting at a higher level and returning to notions of integrative approaches to dispute resolution and “space” for treaty parties to do what is “necessary to resolve the dispute”,170 it is clear that treaties differ with respect to the amount of space and flexibility formally provided to the parties to employ an integrative approach. While none of the treaties surveyed here explicitly preclude parties from engaging in different forms of dispute resolution such as negotiation and mediation, there is significant variance in whether a treaty provides a formal basis for such and the extent to which associated processes are laid out. The GCLCA, for example, includes only passing reference to such,171 whereas the Nisga’a Agreement includes great detail about how the process shall unfold, including that each stage of dispute resolution must be exhausted (or a time frame must expire) before moving to the next. Generally, the staged approach appears to provide more explicit, formal bases for parties to engage in a more problem-solving, less adversarial dialogue.

It is outside the scope of this article, and beyond what would constitute a tenable claim based on the modest analysis herein, to cast judgement regarding such variance across the treaties and associated constraints on the availability of integrative approaches within the treaty implementation sphere. However, to the extent that one regards integrative approaches as potentially helpful in this context,172 particularly those that are reimagined and designed by Indigenous treaty parties to address complexities of culture and power, the limited options for dispute resolution provisions in some treaties, particularly those with the arbitration board model, may present unnecessary constraints on “space” for resolving disputes. Further to the notion that dispute resolution processes should fit the types of disputes anticipated,173 the above review of different treaties demonstrates that not all dispute resolution options are explicitly on the table, particularly in the treaty contexts with an arbitration board model, and as well as in veto contexts where consent from all parties is required to access dispute resolution mechanisms. This lack of “space” for resolving disputes through less formal approaches could hinder fulfilling the purposes of fostering “positive and mutually respectful relationships” between the parties. Further research is required on this point; however, it may be the case that the relatively narrow dispute resolution structure in some modern treaties means that much needed room for cooperative problem-solving and trust-building may not be available – or may not be perceived as available given treaty terms – in some contexts.

5 Conclusion

This review of modern treaty dispute resolution mechanisms shows the wide variance that exists between treaties. From process options, to institutional arrangements, to veto power, to levels of specificity, the treaties present a wide spectrum of dispute resolution methods and articulations. It also reveals a trend, or perhaps an evolution, away from the arbitration board approach and toward the staged approach. However, even within the latter there is significant variance, as the foregoing analysis suggests.

While the treaties present almost a full spectrum of dispute resolution options, there is one significant omission: explicit bases for dispute resolution mechanisms rooted in Indigenous laws and ways of governance. In the fraught context of Crown-Indigenous relations in Canada, and in the specific context of modern treaties, which purport to resolve long-standing disputes and address power imbalances in service of reconciliation, this gap is surprising and potentially problematic.174

At least two contemporary drivers may, however, set the stage for parties to at least begin addressing this omission. First, the significant law and policy reform observable in the contemporary federal political context represents an opportunity to revisit this dimension of modern treaties. The current government appears to have an openness to negotiating such matters. Second, ever increasing work toward revitalization of Indigenous laws and governance175 may provide Indigenous treaty parties with the opportunity to rebuild dispute resolution approaches rooted in traditional or cultural practices. What this might look like can, of course, only be determined by the parties.

Deeper examination of dispute resolution in the Canadian modern treaty context, like other dimensions of modern treaty implementation and broader Crown-Indigenous relationships, will take additional research over many years. This article represents a modest early step. In addition to research regarding revitalization of Indigenous laws and governance applicable in the dispute resolution context, nearer term further research might focus on specific experiences in modern treaty implementation, including how dispute resolution mechanisms have actually been used (or not used), what disputes have actually occurred between treaty parties, and the effects of differences between dispute resolution mechanisms. On the latter point, such research could more deeply examine the observation tentatively offered above – that in some modern treaty contexts limited options for resolving disputes through less formal approaches may hinder much needed trust-building between treaty parties in the broader context of fraught Crown-Indigenous relationships. Such research could focus on how modern treaty dispute resolution mechanisms could further evolve to more effectively serve the core purpose of the treaties to foster “positive and mutually respectful relationships” between the parties.176

Acknowledgments

Research for this article was supported by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council as a sub-grant of the Modern Treaty Implementation Research Project. I am grateful for the collaboration with Dr. Janna Promislow in the research informing this article. I am also grateful to my research assistants, Michelle Tremblay and Niall Fink, for their invaluable assistance and input. Finally, sincere thanks to Professor Nigel Bankes and two anonymous referees for their input on earlier drafts of this article. Any errors are the author’s alone.

NOTES

- 1. Calder v British Columbia (AG), [1973] SCR 313, [1973] 4 WWR [Calder] (wherein the Supreme Court acknowledged the existence of (but did not make a declaration of) Aboriginal title). See also Terry Fenge, “Negotiation and Implementation of Modern Treaties between Aboriginal Peoples and the Crown in Right of Canada” in Terry Fenge & Jim Aldridge, eds, Keeping Promises. The Royal Proclamation of 1763, Aboriginal Rights, and Treaties in Canada (Montreal & Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2015) 105 at 108 (for a general discussion). For detailed commentary on Calder see Hamar Foster, Heather Raven & Jeremy Webber, eds, Let Right Be Done: Aboriginal Title, the Calder Case, and the Future of Indigenous Rights (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2007).

- 2. Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada, “Comprehensive Claims” (13 July 2015), online: Government of Canada <https://www.rcaanc-cirnac.gc.ca/eng/1100100030577/1551196153650> [CIRNAC 2015]. See also “What is a Modern Treaty”, online: Land Claims Agreement Coalition <https://landclaimscoalition.ca/modern-treaty/>.

- 3. CIRNAC 2015, supra note 3.

- 4. Ibid.

- 5. Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada, “Modern Treaties and Comprehensive Land Claims and Self-Government Agreements” (14 May 2019), online (pdf): Government of Canada http://www.aadnc-aandc.gc.ca/DAM/DAM-INTER-HQ-AI/STAGING/texte-text/mprm_pdf_modrn-treaty_1383144351646_eng.pdf [Modern Treaties Map].

- 6. Beckman v Little Salmon/Carmacks First Nation, 2010 SCC 53 at para 12, [2010] 3 SCR 103 [Beckman].

- 7. See e.g. Umbrella Final Agreement between the Government of Canada, the Council for Yukon Indians, and the Government of the Yukon (1993), online (pdf): Government of Canada <http://www.aadnc-aandc.gc.ca/DAM/DAM-INTER-HQ/STAGING/texte-text/al_ldc_ccl_fagr_ykn_umb_1318604279080_eng.pdf> [UFA] (for an illustrative example, which is essentially a template agreement on which 11 Yukon First Nations have based their specific agreements).

- 8. All modern treaties include dispute resolution provisions with one exception: the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement (1975). However, dispute resolution mechanisms were introduced into that regime through subsequent agreements such as the Agreement Concerning a New Relationship Between the Government of Canada and the Cree of Eeyou Istchee (2008), online (pdf): Grand Council of the Crees <https://cngov.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/03_-_agreement_concerning_a_new_relationship_between_the_government_of_c.pdf>.

- 9. See e.g. Land Claims and Self-Government Agreement among the Tłı̨chǫ and the Government of the Northwest Territories and the Government of Canada (2005), online (pdf): Tłı̨chǫ Government <https://www.tlicho.ca/sites/default/files/documents/government/Tłı̨chǫ%20Agreement%20-%20English.pdf> [Tłı̨chǫ Agreement]; Nisga’a Final Agreement between The Nisga’a Nation and Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada and Her Majesty the Queen in Right of British Columbia (27 April 1999), online (pdf): Government of British Columbia <http://www.bclaws.ca/civix/document/id/complete/statreg/99002_41#app_m_m1> [NFA].

- 10. See e.g. Nigel Bankes, “The Dispute Resolution Provisions of Three Northern Land Claims Agreements” in Catherine Bell & David Kahane, eds, Intercultural Dispute Resolution in Aboriginal Contexts (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 2004) at 320.

- 11. Office of the Auditor General of Canada, Chapter 8 – Indian and Northern Affairs Canada – Transferring Federal Responsibilities to the North (Ottawa: Office of the Auditor General of Canada, 2003) at 8.37 – 8.45, online (pdf): Office of the Auditor General of Canada <http://www.oag-bvg.gc.ca/internet/docs/20031108ce.pdf>.

- 12. See Dr. Janna Promislow & Alain Verrier, “Judicial Interventions in Modern Treaty Implementation: Dispute Resolution and Living Treaties” (2019) 6:2 Northern Public Affairs 52; see also Government of Canada, Government of Nunavut, & Nunavut Tunngavik Inc, Moving Forward in Nunavut: An Agreement Relating to Settlement of Litigation and Certain Implementation Matters (2015), online (pdf): <http://www.tunngavik.com/files/2015/05/FINAL-SIGNED-SETTLEMENT-AGREEMENT.pdf>.

- 13. See Julie Macfarlane, “Commentary: When Cultures Collide” in Catherine Bell & David Kahane, eds, Intercultural Dispute Resolution in Aboriginal Contexts (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 2004) at 96; Michael Coyle, “Negotiating Indigenous Peoples’ Exit from Colonialism: The Case for an Integrative Approach” (2014) 27:1 Canadian Journal of Law & Jurisprudence 283. See generally Jeanne M Brett, “Culture and Negotiation” in Roy Lewicki et al, eds, Negotiations: Readings, Exercises and Cases, 7th ed (New York: McGraw-Hill Education, 2015) at 353.

- 14. See Coyle, supra note 14. See also David Kahane, “What is Culture? Generalizing about Aboriginal and Newcomer Perspectives” in Catherine Bell and David Kahane, eds, Intercultural Dispute Resolution in Aboriginal Contexts (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 2004) 28 at 29–33. See also Andrea McCallum, Dispute Resolution Mechanisms in the Resolution of Comprehensive Aboriginal Claims: Power Imbalance Between Aboriginal Claimants and Governments (LLM Thesis, Osgoode Hall Law School, 1993) [unpublished]; Wenona Victor, “Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) in Aboriginal Contexts: A Critical Review”, Canadian Human Rights Commission (April 2007).

- 15. While modern treaties do include explicit provisions requiring consultation, and such consultation may serve to resolve disputes, these treaty mechanisms are outside the scope of this article.

- 16. See Kirk Cameron & Alastair Campbell, “Towards a Modern Treaties Implementation Review Commission”, Northern Public Affairs (22 September 2019), online: <https://www.northernpublicaffairs.ca/index/towards-a-modern-treaties-implementation-review-commission/>. See also Jessica Orkin & Cassandra Porter, “Organizational maladies and bureaucratic prescriptions: The federal Cabinet Directive on Modern Treaty Implementation” (24 November 2015) (paper presented to the Pacific Business & Law Institute’s Aboriginal Law Conference), online (pdf): GoldBlatt Partners <https://goldblattpartners.com/wp-content/uploads/00837995.pdf>. See generally, Christopher Alcantara, “Implementing comprehensive land claims agreements in Canada: Towards an analytical framework” (2017) 60:3 Canadian Public Administration 327.

- 17. Modern Treaty Implementation Research Project, “Modern Treaty Dispute Resolution: Lessons & Prospects” (2017), online: Tłı̨chǫ Government <https://moderntreaties.tlicho.ca/research/indigenous-and-settler-legal-systems/modern-treaty-dispute-resolution-lessons-prospects>.

- 18. Ibid. See also CIRNAC 2015, supra note 3.

- 19. Calder, supra note 1.

- 20. For detailed commentary on Calder, supra note 1, see Foster, Raven & Webber, supra note 2.

- 21. Beckman, supra note 7.

- 22. Modern Treaties Map, supra note 6.

- 23. Beckman, supra note 7.

- 24. Beckman, supra note 7.

- 25. Beckman, supra note 7 at para 9.

- 26. First Nation of Nacho Nyak Dun v Yukon, 2017 SCC 58 [Nacho Nyak Dun].

- 27. Ibid at para 1.

- 28. Christopher Alcantara, Negotiating the Deal: A Comprehensive Land Claims Agreement in Canada (Toronto: University of Toronto, 2013) at 24.

- 29. Ibid at 21.

- 30. See Dwight Newman, “Contractual and Covenantal Conceptions of Modern Treaty Interpretations” (2011) 54 SCLR 475; Julie Jai, “The Interpretation of Modern Treaties and the Honour of the Crown: Why Modern Treaties Deserve Judicial Deference” (2010) 26 NJCL 25.

- 31. See e.g. UFA, supra note 8 at Chapter 11, which is at issue in Beckman, supra note 7.

- 32. See e.g. Beckman, supra note 7; Nacho Nyak Dun, supra note 28; Clyde River (Hamlet) v Petroleum Geo-Services Inc, 2017 SCC 40. See also Promislow & Verrier, supra note 13.

- 33. Nacho Nyak Dun, supra note 28 at para 4.

- 34. Nacho Nyak Dun, supra note 28 at para 33.

- 35. Nacho Nyak Dun, supra note 28 at para 60.

- 36. Yukon Territory’s argument to this effect was rejected in Beckman, supra note 7 at paras 38, 52.

- 37. See John Borrows, “Creating an Indigenous Legal Community” (2005) 50:1 McGill Law Journal 153 at 165 (suggesting that treaties should be regarded as “living agreements”).

- 38. See Coyle, supra note 14. See also Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada, “Guide for the Management of Dispute Resolution Mechanisms in Modern Treaties” (1 Oct 2012), online: Government of Canada <https://www.rcaanc-cirnac.gc.ca/eng/1343831539714/1542729374064> [CIRNAC Guide 2012].

- 39. See e.g. Roger Fisher, William Ury & Bruce Patton, Getting to Yes: Negotiating Agreement Without Giving In, 3rd ed (New York: Penguin, 2011). See also Julie Macfarlane, The New Lawyer: How Clients are Transforming the Practice of Law (Vancouver: UBC Press) at 74–76.

- 40. Coyle, supra note 14. See also Macfarlane, supra note 40 at 74–78.

- 41. See John Kleefeld et al, eds, Dispute resolution: readings and case studies, 4th ed (Toronto: Emond Montgomery Publications Limited, 2016); Alberta Law Reform Institute, “Dispute Resolution: A Directory of Methods, Projects and Resources” (July 1990) at 7–9, online (pdf): Legislative Assembly of Alberta <http://www.assembly.ab.ca/lao/library/egovdocs/1990/alilr/73932.pdf>.

- 42. Ibid.

- 43. Coyle, supra note 14 at 288. See also Fisher et al, supra note 41.

- 44. David Kahane, “What is Culture? Generalizing about Aboriginal and Newcomer Perspectives” in Catherine Bell & David Kahane, eds, Intercultural Dispute Resolution in Aboriginal Contexts (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 2004) at 33–34. See also Don Couturier, “Walking Together, Indigenous ADR in Land and Resource Disputes” (2018) Cdn Bar Assoc at 8, online (pdf): Canadian Bar Association <https://www.cba.org/CBAMediaLibrary/cba_na/PDFs/Sections/ADR-Essay-Contest-Walking-Together.pdf>.

- 45. Kahane, supra note 46 at 45–48.

- 46. Coyle, supra note 14 at 295–303.

- 47. Coyle, supra note 14 at 286.

- 48. Coyle, supra note 14 at 301. See also Couturier, supra note 46.

- 49. Availability of litigation varies in treaty contexts based on subject matter and, in some cases, explicit bars to litigation off-ramps in dispute resolution processes. These are discussed below in Part III.

- 50. Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada, “Cabinet Directive on the Federal Approach to Modern Treaty Implementation” (13 July 2015), online: Government of Canada <https://www.rcaanc-cirnac.gc.ca/eng/1436450503766/1544714947616> [Cabinet Directive].

- 51. Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada, “Statement of Principles on the Federal Approach to Modern Treaty Implementation” (13 July 2015), online: Government of Canada <https://www.rcaanc-cirnac.gc.ca/eng/1436288286602/1539696550968>.

- 52. Cabinet Directive, supra note 52.

- 53. Ibid.

- 54. Carolyn Bennett, Minister of Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada, “Announcement of Canada’s Support for the United Nations Declaration of Indigenous Peoples” (speech delivered at the 15th Session of the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues, New York, 10 May 2016) [unpublished], online: Northern Public Affairs Magazine <http://www.northernpublicaffairs.ca/index/fully-adopting-undrip-minister-bennetts-speech/>.

- 55. Privy Council Office, “Working Group of Ministers on the Reviews of Laws and Policies Related to Indigenous Peoples” (21 February 2018), online: Government of Canada <https://www.canada.ca/en/privy-council/services/review-laws-policies-indigenous.html>.

- 56. Justin Trudeau, Prime Minister of Canada, News Release, “Government of Canada to create Recognition and Implementation of Rights Framework” (February 2018), online: Prime Minister of Canada <https://pm.gc.ca/eng/news/2018/02/14/government-canada-create-recognition-and-implementation-rights-framework>.

- 57. Department of Justice, “Principles Respecting the Government of Canada’s Relationship with Indigenous Peoples” (14 February 2018), online (pdf): Government of Canada <https://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/csj-sjc/principles-principes.html>.

- 58. Department of Justice, “Directive on Civil Litigation Involving Indigenous Peoples” (11 January 2020), online: Government of Canada <https://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/csj-sjc/ijr-dja/dclip-dlcpa/litigation-litiges.html>/.

- 59. Justin Trudeau, Prime Minister of Canada, “Minister of Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Mandate Letter”(4 October 2017), online: Prime Minister of Canada <https://pm.gc.ca/en/mandate-letters/minister-crown-indigenous-relations-and-northern-affairs-mandate-letter>.

- 60. Government of Canada, “Chapter 3: Advancing Reconciliation” (March 2019) at Parts 4, 27; online: Budget 2019 https://www.budget.gc.ca/2019/docs/plan/chap-03-en.html#forgiving-and-reimbursing-loans-for-comprehensive-claim-negotiations. See also, Chantelle Bellrichard, “Budget 2019: $1.4B in loans to be forgiven or reimbursed to Indigenous groups for treaty negotiations”, CBC News (19 March 2019), online: <https://www.cbc.ca/news/indigenous/budget-2019-treaty-loans-forgiven-1.5063128>; House of Commons, Standing Committee on Indigenous and Northern Affairs, Indigenous Land Rights: Towards Respect and Implementation: Report of the Standing Committee on Indigenous and Northern Affairs (February 2018) (Chair: MaryAnn Mihychuk) at recommendations 5, 89, online (pdf): Government of Canada <http://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2018/parl/xc35-1/XC35-1-1-421-12-eng.pdf>; “The Alliance of BC Modern Treaty Nations welcomes treaty loan forgiveness and reimbursement and enhanced fiscal funding accounted in Federal Budget 2019”, Newswire (20 March 2019), online: <https://www.newswire.ca/news-releases/the-alliance-of-bc-modern-treaty-nations-welcomes-treaty-loan-forgiveness-and-reimbursement-and-enhanced-fiscal-funding-announced-in-federal-budget-2019-887460769.html>.

- 61. Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada, “Canada’s collaborative self-government fiscal policy” (27 August 2019), online: Government of Canada <https://www.rcaanc-cirnac.gc.ca/eng/1566482924303/1566482963919>.

- 62. See generally, Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada, “Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs: 2018–19 Departmental Plan” (16 April 2018), online: Government of Canada <https://www.rcaanc-cirnac.gc.ca/eng/1523210699288/1555598120106#sec3_1>.

- 63. Bankes, supra note 11 at 298.

- 64. These agreements were selected because they collectively represent the full spectrum of models and mechanisms. While the Nunavut context is distinctive in that the treaty provided a basis for negotiation toward a new territory and public government, the dispute resolution mechanisms in the land claim agreement are and have always been between the treaty parties. As such, the Nunavut agreement is similar in kind to the other treaties discussed in this article.

- 65. Inuvialuit Final Agreement between the Committee for Original Peoples’ Entitlement, representing the Inuvialuit of the Inuvialuit Settlement Region and the Government of Canada (2005) at 18(16), online (pdf): <https://www.irc.inuvialuit.com/sites/default/files/Inuvialuit%20Final%20Agreement%202005.pdf> [IFA].

- 66. Ibid, s 18(17).

- 67. IFA, supra note 73, s 18(33). See also s.18(34) (listing additional areas of jurisdiction such as enrolment, land matters, and wildlife compensation awards).

- 68. Though there are explicit constraints laid out in s 18(34) clarifying that the IFA arbitration process does not apply to the rights of another modern treaty group unless they consent.

- 69. IFA, supra note 73, s 18(36)(a).

- 70. IFA, supra note 73, s 18(36)(b).

- 71. IFA, supra note 73, s 18(36)(f).

- 72. IFA, supra note 73, s 18(36)(g).

- 73. IFA, supra note 73, s 18(36)(h).

- 74. IFA, supra note 73, s 7(12). See also s 7(57).

- 75. See e.g. IFA, supra note 73, s 7(64) (regarding acquisition of lands for public road rights of ways).

- 76. IFA, supra note 73, s 18(3). Under s 18(5) the Chairman and Vice-Chairman are appointed by Canada, but they must “be acceptable to the Inuvialuit and Industry”.

- 77. IFA, supra note 73, s 18(5).

- 78. For the purposes of the appointment power, Industry is defined to mean the five largest commercial industrial entities in the ISR based on assets in the region. See IFA, supra note 73 at 18(7).

- 79. IFA, supra note 73, s 18(6).

- 80. IFA, supra note 73, s 18(14).

- 81. IFA, supra note 73, s 19(32).

- 82. Bob Simpson (Director of Intergovernmental Relations, Inuvialuit Regional Corp.), “The Inuvialuit Arbitration Process”, online (pdf): Land Claims Coalition http://www.landclaimscoalition.ca/assets/Bob-Simpson-Dispute-Resolution.pdf. See also Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada, Inuvialuit Comprehensive Land Claim Agreement – Annual Report of the Implementation Committee April 1, 2004 – March 31, 2005, online: Government of Canada <https://www.rcaanc-cirnac.gc.ca/eng/1374866904715/1543249886337?wbdisable=true>.