Figure 1. The formal process of applying for licenses.

Maria Ackrén*,

Department of Social Sciences, Ilisimatusarfik/University of Greenland, Nuuk, Greenland

Abstract

Since the Greenland Self-Government Act came into force in 2009, economic development and the right to utilize natural resources in Greenland lies in the hands of the Self-Government. Earlier efforts to establish this authority were made back in the 1970s, when discussions on Home Rule were first on the agenda. Mining industries are not a new activity in Greenland. During the Second World War, Greenlandic cryolite was used to produce aluminum for the North American aircraft industry. Other essential natural resources, such as gold and gemstones, have also received international interest over the years. Greenland’s new development aim is to build up a large-scale mining industry. This article elucidates the form of public consultation processes followed in Greenland in connection with two large-scale mining projects and the different views various actors have regarding these events. How did the deliberative democratic process unfold in Greenland regarding these projects? Was the process followed an effective way to manage these kinds of projects? The article shows that two projects that received a lot of media attention: the 2005 iron ore mine project in Isukasia, and the 2001 TANBREEZ-project to extract rare earth elements, used highly different approaches when it comes to deliberative democracy. In the former case, a limited degree of deliberative democracy was used, while in the latter case, the opposite applies.

Keywords: public consultation processes; deliberative democracy; mining; Greenland

Received: October 2015; Accepted: March 2016; Published: May 2016

*Correspondence to: Maria Ackrén, Department of Social Sciences, Ilisimatusarfik/University of Greenland, PB: 1061, 3900 Nuuk, Greenland. Tel: +299 38 56 63 (Office). Email: maac@samf.uni.gl

©2016 M. Ackrén. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), allowing third parties to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format and to remix, transform, and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercially, provided the original work is properly cited and states its license.

Citation: M. Ackrén. “Public consultation processes in Greenland regarding the mining industry.” Arctic Review on Law and Politics, Vol. 7, No. 1, 2016, pp. 3–19. http://dx.doi.org/10.17585/arctic.v7.216

In the process of building up Greenland’s mining industry after the Government of Greenland took over the mineral resources sector,1 heavy criticism against the procedures and processes around the extractive industries has come from various stakeholders. The local populations in the areas where mining will take place feel that they have not received enough information about all of the challenges and possible impacts of the mining projects,2 even though several public consultation processes have been carried out. One of the biggest criticisms is that locals were first included in the process at a late stage, and after all major decisions had already been made. Some politicians claim that people were informed several years ago, and that current developments should therefore not have come as a surprise. There are thousands of pages of technical data available on the Internet about each of the projects, but these documents are difficult to read and interpret. Another problem lies in the form of the public consultation processes themselves. They primarily consisted of information meetings to the public, and did not take the form of consultation processes more frequently used, for instance, in Canada, where various actors and stakeholders are involved from the beginning to the end, and therefore have more influence on decisions made.

Public consultation and participation in these large-scale mining projects has to be viewed against a backdrop of wider political participation. Political and economic development in Greenland has progressed rapidly. It is therefore important to examine how public or political participation has evolved in a general context in order to analyze the forms of public consultation and hearing processes now taking place in relation to Social Impact Assessments (SIAs) and other processes related to the extractive industry.

Political participation applies to all forms of political actions made by individuals. In democracies, the most obvious form of political participation is through voting in elections, consultation processes, referendums and so on. Aside from government initiatives, other forms of action include demonstrations, boycotts and more aggressive forms of action, such as the occupation of buildings.3 The promotion of active citizenship as a new form of participation seen is a shift in government towards a form of “governing through communities” where citizens share responsibility for the defense of citizen rights as a strategy of increasing participation in the political process. Examples include parents raising funds for schools, residents joining “neighborhood watch” schemes to guard against crime, and other forms of civic participation that extend beyond the act of voting.4

In the literature on the issue of political participation, three ideal models are usually referred to: electoral democracy, participatory democracy and deliberative democracy. The first model of electoral democracy refers to the act of voting as the main channel for citizens to influence politics. After election day, responsibility is transferred to the elected representatives. The second model of participatory democracy emphasizes more participation from citizens in the form of active participation in decision-making. This form is realized through the decentralization of politics to local communities. The third model of deliberative democracy focuses on a process of dialogue and discussion to influence political decisions directly and not through representatives, and where arguments compete against each other before a decision is eventually made.5

All three forms of democratic participation are evident in the Greenlandic community. The element of electoral democracy is, however, quite young, since historically Greenland has been ruled by Denmark under the auspices of colonial rule from 1721 to 1953. The colonial framework gave Greenlanders limited room for political participation. With the integration of Greenland into the Danish realm, some political participation was made possible, and eventually when Home Rule was introduced in 1979, a regional political system with elections was created. The extended self-rule established in 2009 has further broadened the scope of political participation for Greenlandic citizens. Participatory democracy is used on the local level within the municipalities, even though this form has been somewhat restricted due to municipal reforms that took place in 2009, reducing the number of municipalities from 18 to 4. Deliberative democracy is the closest Greenland has to public consultation processes or hearing processes in relation to the mining industry projects. This is not the only context that deliberative democracy is used. It is tradition in Greenland to conduct hearing processes regarding law proposals on general matters.6 Is the deliberative democracy model feasible and what are the benefits and drawbacks of using such a model in the context of economic development in Greenland? How can the hearing processes be improved if there is a lack of trust and legitimacy amongst the population?

Section 2 of the article provides a short history of Greenland’s legislative competencies in the field of mineral resources. Section 3 examines the current situation in relation to Self-Government, Sections 4 and 5 present case studies of the Isukasia-project and the TANBREEZ-project and compare the two projects. The final section draws conclusions based on the findings in the article.

Mining projects have been part of Greenland’s history since the 19th century. Cryolite, a raw material once important to the aluminum smelting process, was mined until resources were depleted in 1987.7

The first law in relation to onshore and offshore industrial extraction in Denmark was passed in 1932. At this time, it was only possible to enforce laws in Greenland through a Royal Decree, which was passed in 1935, applying the same Danish law within the area.8 Greenland was still a colony at the time, so all major decisions were made in Copenhagen.

The Danish law on industrial extraction was modified in 1950, and stated that “Resources in Greenland soil belonged to the Danish state.” Administration in Greenland was centralized, and a directly-elected provincial council was established in Nuuk with a single governor. In 1953, Greenland became an integral part of the Danish Realm as a county, and Denmark awarded Greenland two representatives in the Danish parliament.9 In January 1960, the Danish Ministry for Greenland appointed a commission to prepare a specific law on mineral resources in Greenland. The outcome of this work was a law, which was implemented in 1965. The aim of the law was to attract foreign investors to invest in extraction activities in Greenland.10

In 1975, political negotiations between Greenland and Denmark took place regarding the future constitutional status of Greenland. Greenland had been an integrated part of Denmark as a county since 1953, but this was now about to change. Political mobilization against postcolonial rule was on the agenda, and Greenland wanted more autonomy. The negotiations ended in a 1979 referendum on Home Rule, following the Faroese model. A majority of the Greenlandic population voted in favor of Home Rule.11

During the negotiations between Denmark and Greenland on Home Rule, the issue of ownership of minerals and petroleum in the subsoil of Greenland was discussed, but a separate 1978 law (Law on minerals in Greenland) established joint administration and responsibility over the area. A committee consisting of an equal number of Greenlandic and Danish parliamentarians was to make decisions on permits to companies who wished to start operations in Greenland. The administration of the committee was situated in Denmark under the jurisdiction of the Danish Minister for Greenland.12 Home Rule in Greenland was established in 1979, giving Greenland full control over administration of the country in self-financed areas and some control over policy implementation in spheres subsidized from Denmark, but as mentioned above, natural resources were considered as a joint matter.

In 1988, the 1978 Danish law was amended for the first time. The principle of sharing revenues from the extractive field shifted in favor of Greenland. The joint Greenlandic-Danish company, Nunaoil A/S (established in 1985), was also strengthened. This was also a result of the 1985 Greenlandic referendum, the outcome of which led Greenland to leave the European Economic Community (EEC). In 1991, minor changes were made to the 1978 Danish Law, the most significant of which was the requirement to provide more information to the public in Greenland about all activities going on. Furthermore, the administration of hydropower activity was moved from the sphere of joint affairs between Greenland and Denmark to the Home Rule administration.13

In 1998 a further step towards managing extractive industries was taken when the Greenlandic Home Rule Government established the Bureau of Minerals and Petroleum (BMP). The Mineral Resources Act was passed in 2009 and came into force in 2010. In article 1 the Act states the following:

This Act was a direct result of the introduction of Self-Government, which had come into effect on 21 June 2009. In the Self-Government Act of 2009, §§7–8 are related to incomes from the extractive industries.15 The Mineral Resources Act regulates onshore and subsoil activities. The Act also states that all activities should take social (health and safety), environmental and sustainability considerations in mind. Furthermore, international practices and best practices are acknowledged.16 This acknowledgement is also found in the Memorandum of Understanding that the BMP signed with the National Energy Board in Canada in 2010. This agreement’s purpose is to exchange experiences about management practices and issues concerning the extractive industries. It is an agreement where “best practices” are in the forefront regarding regulations and procedures within the field.17

On 1 January 2010, Greenland took over control of all subsurface resources, thus paving the way for direct negotiations between the Greenlandic authorities and multinational companies interested in investing in Greenland.18 In recent years, an increasing number of mineral exploration licenses have been granted to foreign mining companies, from Canada, Australia, the UK and other countries.19

Public involvement has become more active in recent years, starting with the first protest campaign against offshore exploratory drilling for oil and gas west of central Greenland in 1976–77. There have also been other protests, from both the public and the Greenlandic parliament, but it was not until the 2000s that public involvement was organized in the form of non-governmental organizations (NGOs), such as Avataq and Inuit Circumpolar Council (ICC). Furthermore, Alcoa’ inquiry in 2006 to build an aluminum smelter in Maniitsoq triggered politicians to demand that a Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) be conducted in the process, even though no legislative basis for such a process had ever been introduced in Greenland before.20

With the introduction of Self-Government, a new era in the extractive industries began, and increasing numbers of Greenlanders have been hired as workers and given relevant education in the field. These activities are followed closely by politicians, non-governmental organization (NGOs), the public and the press. Almost every day the local media (e.g. Kalaallit Nunaata Radioa/Greenlandic Broadcasting Corporation (KNR)), the newspapers (Sermitsiaq.ag and Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten) report on the industry.

BMP, a government agency under the Ministry of Industry and Mineral Resources, actively campaigned to encourage resource companies and investors to think about exploration and exploitation opportunities in Greenland. In addition, BMP was responsible for management, administrative and regulatory tasks regarding petroleum and mineral resources and had sole authority and decision-making power to issue licenses for prospecting, exploration and production.21 As of 1 January 2013, BMP was renamed the Mineral License and Safety Authority (MLSA). The responsibilities of the former BMP were distributed across several administrative units – the Ministry of Industry and Minerals, and a new Environment Agency for Mineral Resources Activities (EAMR), which falls under the Ministry of Nature and Environment. This reorganization was the result of a revision of Greenland Parliament Act No. 26 of 18 December 2012, an amendment of Greenland Parliament Act No. 7 of 7 December 2009 (The Mineral Resources Act).22

The new Authority is an improvement, since now there is a separation between the management of mineral resources and environmental management. This separation also takes the form of different supervisory and approval roles regarding strategic planning and marketing.23 The EAMR safeguards environmental protection related to oil extraction and mineral extraction in collaboration with the Danish Center for Environment and Energy (DCE) at Aarhus University and the Greenlandic Institute of Natural Resources (GINR). These two institutes together carry out strategic environmental impact assessments (SEIAs) that determine which on- and offshore areas should be opened for a licensing round.24

The ICC and the Employers’ Association of Greenland have taken a leading role in the call for public debate on the nature of consultation and decision-making processes in the extractive industries. In October 2012, ICC launched a project in cooperation with WWF-Denmark to focus on improving hearing processes for large-scale projects in Greenland. Transparency Greenland is another NGO that has tried to influence decision-makers, addressing concerns regarding corruption within the industry, and arguing that citizens should become more involved in the discussions on legislation for large-scale projects.25 Another issue addressed by Transparency Greenland has been to call for more streamlined procedures regarding public consultation, and also to improve access to relevant documents, which are often only in English and not translated into Danish and/or Greenlandic.26

The Government of Greenland has also taken steps towards getting the public more involved in the process. One of the Government’s major goals is to inform and involve citizens and other stakeholders in the planning of future mining projects through a variety of activities, including meetings, focus groups, interviews, communication via media sources, seminars, conferences and mass meetings.27

Public participation is usually integrated in environmental impact assessment (EIA) and SIA processes, since the authorities often require public consultations as part of EIA and SIA preparations. However, there are no clear guidelines for how public consultations or hearing processes should be conducted.28 In the Mineral Resources Act (MRA) of Greenland it states that a license for approval of a mineral activity can be granted only after an assessment has been made of the impact on the environment (EIA) or when a social sustainability assessment (SSA) has been conducted.29 In the 2014 revisions of the MRA an additional Part 18a, §§87a–d requires pre-consultation and consultation for large-scale projects.30 In the Aarhus Convention, this is one of the international conventions that guarantees access to information, public participation and access to justice in environmental issues, Denmark made a reservation for Greenland. Greenland has yet to ratify the Convention.31 Public consultations or hearing processes are used to mitigate conflicts and serve as a tool for information exchange between various stakeholders, and may also enhance mutual learning processes and act as a means to avoid costly delays with large-scale projects.32

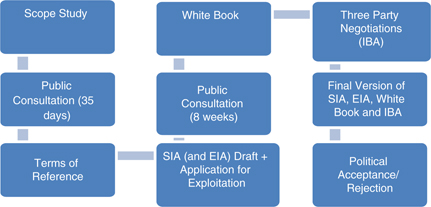

The formal process of public consultation or outlining a Social Impact Assessment is comprised of multiple stages, but is straightforward33: 1) First, there is a scope study, which is a pilot study over the planning and collection of data for the place of the project. During this phase, all relevant stakeholders are informed and should participate regarding the matters to be investigated in such a scope study; 2) after the scope study is completed, there is a 35-day public consultation. During this period, stakeholders can apply for funding to undertake investigations of their own. This new and improved procedure was implemented in 2014. The initiative helps locals, NGOs and associations gather information from neutral sources already at the stage of the scope study; 3) when all information has been gathered and the scope study and the public consultation approved, the next procedure is for the company to write the terms of reference. This terms of reference document is then sent to the authorities for approval. The terms of reference is a more detailed document and can be seen as a committee report. This document is not submitted for a public hearing; 4) a draft for an SIA and an EIA is the next step in the process, if the project is considered to have a significant impact on society. During this stage the document(s) constitute the basis of the next public consultation. The public hearings span 8 weeks. The form these public consultation meetings take can vary, and can include: stakeholder meetings, local meetings with citizens, public hearings and/or information meetings; 5) the White Book is then written. The purpose of the White Book is to address relevant concerns raised during the public consultation meetings. All of the concerns raised should be included in this document; 6) the next step is the three-party negotiations regarding the Impact Benefit Agreement (IBA). This is the agreement between the authorities (municipality and the government) and the company. The IBA is published after it is approved34; 7) after all these stages, and if the project has been successfully outlined in each phase, the final version of the White Book together with the final versions of SIA and EIA are sent to the government for political approval. The Government of Greenland will then either accept or reject the proposal for exploitation.35

The procedure is illustrated in Figure 1:

Figure 1.

The formal process of applying for licenses.

The deliberative democratic ideal takes citizen participation into account. Citizens should be able to be involved in the process of decision-making and be able to influence political decisions directly and not through representatives. Interests should not be contradictory, and all participants should be economically independent and have the same access to information.36 This is, of course, an ideal form of deliberative democracy. There are several concerns that can be addressed in relation to the process of large-scale projects in Greenland. First, the companies have a large degree of knowledge in their field. They usually also have expert resources available in their companies. Second, the authorities have first-hand information on every project that is in progress, and may also have experts that provide consulting or advisory support. In comparison, the municipal authorities and local citizens can be seen as resource-weak stakeholders. This also applies to NGOs and other interest organizations within society. Access to knowledge and information can therefore be on an unequal footing. Third, the practice of public consultation might not be implemented in a meaningful way, and the situation that Greenland has not ratified the Aarhus Convention is problematic. Another consideration is specific cases of large-scale projects, which can vary significantly from case to case. In the next section, two examples cases are examined with regard to the public consultations processes undertaken so far in relation to the deliberative democratic feature.

In this section the London Mining Greenland A/S, or Isukasia-project, and the TANBREEZ-project are outlined.

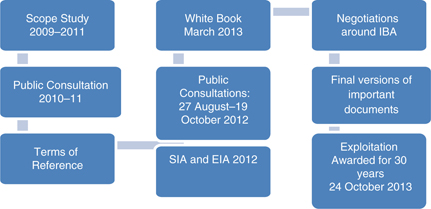

London Mining is a British company that produces high specification iron ore for the global steel industry. London Mining has received a 30-year exploitation license for their Isukasia-project in Greenland effective 24 October 2013.37

The iron ore resources at Isua were first discovered in 1965, but it was not until an exploration drilling and feasibility campaign was undertaken by Marcona in the 1970s that the potential for open pit and underground mines was revealed, which coincided with the development of a bulk logistics route to a deep water port. Rio Tinto carried out further exploratory drilling in the 1990s, and London Mining acquired the Isua license in 2005.38

In 2012, London Mining Greenland A/S applied for exploitation rights, and later signed the exploitation agreement. A public hearing phase and public community meetings have been completed.39

A potential mine will be able to produce around 15 million tons of ore concentrate per year. The project is expected to employ more than 3000 employees during the peak construction phase. When the mine moves into the production phase, the company expects that employment levels will stabilize between 680 and 810 individuals.40 This means that a foreign labor force will have to be brought in to cover the construction phase. London Mining intends to employ Chinese workers not only for the construction phase, but throughout the whole process, including the production phase.41

London Mining conducted an SIA in 2009. During the period 27 August 2012 to 19 October 2012, BMP organized four public hearings. In addition, London Mining organized a number of public consultation meetings with relevant stakeholders as well as the public on general issues concerning engineering and the environment and socio-economic impacts of the Isukasia-project.42

Public hearings were conducted on four main topics: a general information session, a session about the SIA-process, a session about the EIA process and a concluding session on all topics in the form of an open debate.43

From 2008 to 2012, London Mining implemented an extensive communication plan and involvement with the local community. In 2011 and 2012, the company held 10 public consultation workshops to discuss environmental, social and technical aspects of the Isukasia-project with the local citizens. Furthermore, three large public information meetings with media coverage and presentations were held in 2010 and 2011.44

The results of the hearing processes can be seen in light of both benefits and risks. Some of the key benefits are economic and social. There will be opportunities for both direct and indirect employment and local business development, as well as increased opportunities for education and training. The risks can be summarized as social conflicts between vulnerable groups in society and the risk of pollution and accidents.45

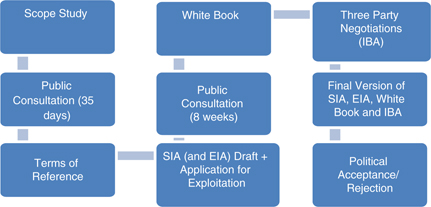

As can be seen from Figure 2, the time frame for public consultation and involving different actors was quite short for such a large-scale project. The scope study that London Mining submitted was highly detailed. This process was completed before the improved legislation came into force, and hence the public consultation period where the SIA and EIA were discussed spanned only 4 weeks (currently 8 weeks). In the public and media debates, the local people pointed to the potential negative impacts the project would have and raised concerns regarding the environmental and social impacts the project would have on hunting and the environment at large.46 The form the public consultation took is problematic. First of all, the company itself decided to what extent public consultation was carried out. Second, Naalakkersuisut (Greenland’s Government) used a local consultancy firm with clients in the mining sector to chair proceedings. During the hearings, which took place at Ilisimatusarfik (the University of Greenland), company employees and consultants from Denmark and Canada hired by London Mining summarized several thousand pages of technical reports and other reports to get their message across. The hearings were clearly information meetings and did not take the intended form of dialogue between stakeholders.47

Figure 2.

The formal process of London Mining.

During the public hearing, people expressed their frustration over a lack of democratic involvement – for example, the audience was told that questions could be asked at the end of the meeting, but they would not be answered until the following session. This is only a form of one-way communication to the public, and not the real, deliberative form of discussion that is the purpose of such hearings.48 At a minimum, public involvement must provide an opportunity for those directly affected to express their views regarding the proposal and its environmental and social impacts.

There have also been other signs of discontent. On Monday 26 November 2012, around 20 people demonstrated outside the Greenlandic parliament building, over the issue of using a foreign labor force. This was at the time when the MRA was up for debate in the parliament. The demonstration was organized by “Foreningen 16. August.” The name of the association was taken from an incident where BMP banned local people from gathering red rubies and other gemstones in an area that had attracted the interest of the Canadian company True North Gems.49 Several demonstrations have been organized by different associations in Greenland against other large-scale projects. This is a way of showing dissatisfaction with the way the authorities are handling these matters. In Greenland, this can sometimes be an effective way of dismantling the whole government, which happened recently over the Aleqa-scandal (October 2014), when thousands of people demonstrated against corruption in the Government.

Recently, London Mining has been affected by international problems, such as the Ebola-epidemic in Africa and falling iron ore prices. The company’s financial situation is ruined, and it is now under administration.50 The Isukasia-project has therefore been put on hold. Other investors have come into the picture recently, such as General Nice Development Limited, which is Hong Kong-based and has its main operational center in Tianjin City on mainland China. General Nice Development Limited is part of a conglomerate, meaning that business can go on. However, there are a number of issues that need to be resolved before mining operations can commence.51 Both external and internal problems and uncertainties can delay large-scale projects of this magnitude.

The TANBREEZ-project is an acronym for the minerals that will be extracted from the mine. The project belongs to the Australian company Rimbal Pty. Ltd. headed by Greg Barnes. TANBREEZ Mining Greenland A/S was established in 2010 and is 100% owned by Greg Barnes. The project is close to some of Southern Greenland’s major towns (Narsaq, Qaqortoq and Nanortalik) and only 38 km from the international airport of Narsarsuaq.52 It is estimated that Kringlerne (the place where the mine will be situated) contains 28 million metric tons of rare earth ore, of which 30 percent is thought to be heavy rare earth elements (REE). Contrary to many REE projects around the world, Kringlerne does not contain uranium or thorium, making the refining process easier.53

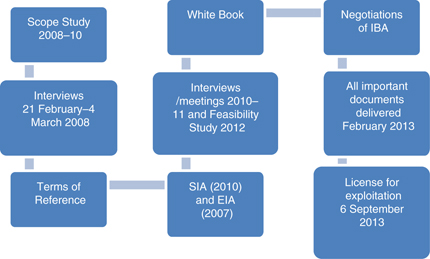

A license for exploration was obtained in 2001 by Rimbal Pty. Ltd. The project has offices in both Perth, Australia and Nuuk, Greenland. Currently, a team of 10 people is working on the project. An Environmental Impact Assessment and a Social Impact Assessment were submitted in 2007 and 2010 respectively. Some field investigations were conducted in 2010 and a feasibility study was completed in 2012.54

The project is expected to have duration of over 20 years, and the construction phase is estimated to take 2–5 years. The expected workforce during both the construction and operation phases is 80 persons. A yearly income when the mine is in operation is to be expected to be about DKK 13 million.55

So far, the company has conducted a local use study, which was finalized in August 2013. The information in this study was based on interviews with local stakeholders in South Greenland. Between the period of 21 February and 4 March 2008, 40 persons engaged in hunting, fishing, sheep farming, tourism, museum activities, recreational use of natural areas, stone/mineral collection and public administration were interviewed. In April 2010, five additional interviews were conducted by phone with people living outside the towns, and later about 20 more interviews were undertaken with fishermen and hunters in the area.56

TANBREEZ has also conducted an EIA and several reports have been written about the natural environment, climate and hydrology, archeology and other relevant fields during the EIA process.57

Concerns regarding the TANBREEZ-project have been of a different character than concerns raised in connection with the Isukasia-project. The most obvious concerns relate to the fishery interference, because the mining activities will lead to more boat traffic in the area. Another issue is the risk of pollution and accidents. On a more positive note, the TANBREEZ-project will lead to more direct and indirect employment. The company has promised that 90% of its workforce will be local during both the construction and production phases.58

There has been a request to extend the public hearings on the TANBREEZ-project, which the company accepted 9 of December 2013. During the period 17–19 November 2013, several public hearings took place in South Greenland. The deadline was 6 January 2014 for commenting on these hearings.59 As can be seen in Figure 3, the TANBREEZ-project has used interviews with local stakeholders and public hearings as their primary way of communicating with the public. The process has been quite transparent. Additional public hearings were held after the license for exploitation was accepted. It seems that TANBREEZ’s policy has been to include as many stakeholders as possible from the beginning, and involve them in an ongoing dialogue.

Figure 3.

The formal process of the TANBREEZ-project.

The current situation of the TANBREEZ-project is uncertain. The latest online news is from 24 March 2014, which states that the company will participate in Hong Kong at the Mines and Money Conference and the Alkaline Conference in Russia in August 2015.60 The project is waiting to begin with the construction phase at the moment.

The two large-scale projects mentioned above are of a different character. All large-scale projects in Greenland and elsewhere are usually evaluated and processed individually, since mining is a complex procedure, especially when various minerals are at stake. The nature of mining has become a very complex issue in the world at large. It is as impossible to compare two mining projects as it is to compare two mining countries with each other. Every project is unique and every context is different.

As has also been argued, the companies’ policies differ in the way they have included the public. London Mining had a clear top-down strategy: it decided what kind of public hearings it wanted, and intended to employ a foreign workforce. London Mining did not promise any significant involvement of local workers, instead it looked towards China for both workers and funding. There has been a lot of criticism directed towards the project during its progress as mentioned earlier in the article, and now with the current unstable world market and world geopolitical situation, the company is functioning under administration and can be said to be more or less dysfunctional. The whole project has come to a halt, and the future is uncertain, even with new investors.

TANBREEZ has used a completely different approach. The company has actively involved locals from the beginning, and used interviews to interact with various stakeholders. Public hearings were held on several occasions, with additional hearings scheduled following new developments. These hearings have helped build trust with the local community. The policy has been more bottoms-up, where the company has done everything according to the deliberative ideal. The company is also promising to use locals as much as possible within the project.

In Canada, a commissioner has been appointed by the authorities to go through a company’s application for mining rights. In this way, there is an independent party in charge of involving stakeholders and the general public, promoting a more democratic procedure. The commissioner is also in charge of public consultations and hearings. Accordingly, the overall process has more legitimacy, and there is more trust between the authorities, companies and the public.61 This could be an idea for the Greenlandic authorities to take into account in the future.

The Government of Greenland, and especially the Ministry of Industry and Mineral Resources and the Ministry of Nature and Environment, has worked on improving the conditions and regulations regarding the mining sector continuously. The amendments to the MRA from 2014 now include pre-consultation and consultation in the Act. This is a learning process, and it will probably continue to be improved for the years to come. It is evident that Greenland is not yet capable of handling large-scale projects on its own, and is therefore dependent on external expertise in this area.

The current economic situation makes it difficult to predict what will happen to all of the ongoing mining projects in Greenland. Greenland’s economy, like that of many other countries, is in bad shape and the country is highly dependent on investment from abroad. However, with the recent decline in commodity prices on the world market, it will probably take some time before the real mining adventure becomes a reality.

Is deliberative democracy feasible in Greenland in relation to large-scale projects? The answer would be both yes and no. This article is, of course, limited in that it only takes two examples into account, but it does seem difficult to make deliberative democracy work in the context of large-scale projects of the magnitude of the Isukasia-project. With smaller projects like TANBREEZ, this process has proven feasible. Much depends on the company’s policy and the agreements made with the authorities in the first place. Another issue is how public consultation is conducted. If it only takes the form of information meetings, no formal deliberative process is at stake, but if the public, stakeholders and other interest groups are interviewed, they become more involved in the process. The feasibility to use more direct involvement in these kinds of projects also depends on the scale and what kind of project it is.

A large company with a top-down management style and clear hierarchical structure might not be used to handling deliberative processes within the company itself. It therefore becomes harder to use this form in other contexts, while a smaller company might have a completely different approach to management and be used to deliberative processes both within and outside the company’s framework. However, this issue needs further investigation.

Legislation in the area of mineral resources is also crucial. The MRA in Greenland might not cover all the aspects of the deliberative process or take into account its full potential. It merely provides guidelines in this area and not clear regulations or legislation. The fact that Greenland stands outside the Aarhus Convention should also be stressed, since this piece of international law might help to improve the deliberative process within this particular field.

The author would like to thank the two anonymous peer reviewers for their constructive criticism and helpful suggestions on an earlier version of this article. The author would also like to thank all participants at the NOPSA-workshop: “Political Science Research in the Arctic” in 2014 for their comments and suggestions and colleagues at the Arctic Circle Assembly in Reykjavik in 2014 for improvements of an earlier draft of this article. The author is solely responsible for the content of this work.

1. Bent O. G. Mortensen, “The Quest for Resources – The Case of Greenland,” Journal of Military and Strategic Studies 15, no. 2 (2013): 98.

2. Bent O. G. Mortensen, op. cit., (2013): 103–5; and Cécile Pelaudeix, “Governance of Arctic Offshore Oil & Gas Activities: Multilevel Governance & Legal Pluralism at Stake,” in Arctic Yearbook 2015, ed. Lassi Heininen et al. (Akureyri: Iceland, Northern Research Forum, 2015), 6. http://www.arcticyearbook.com/

3. Robert J. Jackson and Doreen Jackson, Contemporary Government and Politics: Democracy and Authoritarianism (Scarborough, Ontario: Prentice Hall Canada Inc., 1993), 119–20; and W. Phillips Shively, Power & Choice: An Introduction to Political Science, 4th ed. (New York, USA: McGraw-Hill Inc., 1995).

4. Martin Jones, Rhys Jones, and Michael Woods, An Introduction to Political Geography: Space, Place and Politics (London: Routledge, 2004), 142–5.

5. Åsa Bengtsson, Politiskt deltagande [Political Participation] (Sverige: Studentlitteratur, 2008), 50–1.

6. See e.g. Sara Bjørn Aaen, Demokratisk legitimitet i høringsprocesser i forbindelse med storskala-projekter i Grønland (Nuuk: Grønlands Arbejdsgiverforening, 2012).

7. Tim Boersma and Kevin Foley, (eds.) “The Greenland Gold Rush: Promise and Pitfalls of Greenland’s Energy and Mineral Resources,” in The John L. Thornton China Center and the Energy Security Initiative (Washington D.C: Brookings, 2014), vi.

8. Klaus Georg Hansen, “Greenlandic Perspectives on Offshore Oil and Gas Activities – An Illustration of Changes in Legitimacy Related to Democratic Decision Processes,” Journal of Rural and Community Development 9, no. 1 (2014), 140.

9. Tim Boersma and Kevin Foley, op. cit., 8.

10. Klaus Georg Hansen, op. cit., 141.

11. Maria Ackrén and Bjarne Lindström, “Autonomy Development, Irredentism and Secessionism in a Nordic Context,” Commonwealth & Comparative Politics 50, no. 4 (2012): 503.

12. Klaus Georg Hansen, op. cit., 142.

14. Greenland Parliament Act of 7 December 2009 on Mineral Resources and Mineral Resource Activities (the Mineral Resources Act). http://www.govmin.gl/images/stories/faelles/mineral_resources_act_unofficial_translation.pdf

15. Lov om Grønlands Selvstyre, nr. 473, Lovtidende A 2009, udgivet den 13. juni 2009 (Greenland’s Self-Government Act of 2009).

16. The Mineral Resources Act. https://www.govmin.gl/images/stories/faelles/mineral_resources_act_unofficial_translation.pdf

17. Memorandum of Understanding between the Ministry of Mineral Resources of Greenland and the National Energy Board of Canada Regarding Cooperation. https://www.neb-one.gc.ca/bts/ctrg/mmrndm/2015-07-31mnstrmnrlrsrc-eng.html

18. Mark Nuttall, “Zero-Tolerance, Uranium and Greenland’s Mining Future,” The Polar Journal 3, no. 2 (2013): 370.

19. Mark Nuttall, ibid., 372. See also List of Mineral and Petroleum Licenses in Greenland. https://www.govmin.gl/images/list_of_licences__20160216.pdf for a current update regarding the licenses.

20. Klaus Georg Hansen, op. cit., 144–50. See also Anne Merrild Hansen and Lone Kørnøv, “A Value-Rational View of Impact Assessment of Mega Industry in a Greenland Planning and Policy Context,” Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal 28, no. 2 (2010): 135–45.

21. Mark Nuttall, op. cit., 373–4. See also the following link: http://www.govmin.gl/

22. Report to Inatsisartut on Mineral Resource Activities in 2013: Annual Report 2013, Naalakkersuisut – Government of Greenland, http://www.govmin.gl/images/stories/about_bmp/publications/R%C3%A5stofredeg%C3%B8relse UK 28-februar 2014.pdf

24. Tim Boersma and Kevin Foley, op. cit., 18.

25. Mark Nuttall, op. cit., 376.

26. Tim Boersma and Kevin Foley, op. cit., 22.

27. Report to Inatsisartut on Mineral Resource Activities in 2013: Annual Report 2013, ibid.

28. Anna-Sofie H. Olsen and Anne Merrild Hansen, “Perceptions of Public Participation in Impact Assessment: A Study of Offshore Oil Exploration in Greenland,” Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal 32, no. 1 (2014): 72.

29. See The Mineral Resources Act, §73 and §76. https://www.govmin.gl/images/stories/faelles/mineral_resources_act_unofficial_translation.pdf

30. See Amendments of the Mineral Resources Act from 2014, Part 18a, §§87a-d. https://www.govmin.gl/images/stories/about_bmp/Unofficiel_translation_-_Mineral_Resources_Act_as_amended_by_act_no_6_of_june_8_2014_-_pdf.pdf

31. Cécile Pelaudeix, “Governance of Arctic Offshore Oil & Gas Activities: Mulitlevel Governance & Legal Pluralism at Stake,” in Arctic Yearbook 2015, ed. Lassi Heininen et al. (Akureyri: Iceland, Northern Research Forum, 2015), 5–6. http://www.arcticyearbook.com/; See also The Aarhus Convention. http://ec.europa.eu/environment/aarhus/

32. Anna-Sofie H. Olsen and Anne Merrild Hansen, ibid.

33. See Amendments of the Mineral Resources Act from 2014, Part 18a, §§87a-d. https://www.govmin.gl/images/stories/about_bmp/Unofficiel_translation_-_Mineral_Resources_Act_as_amended_by_act_no_6_of_june_8_2014_-_pdf.pdf

34. The IBA is not mentioned in the MRA, but is included in the Guidelines for Social Impact Assessments for mining projects in Greenland. https://www.govmin.gl/images/stories/minerals/sia_guideline/sia_guidelines.pdf

35. This is in more detail elaborated in Vurdering af Samfundsmæssig Bæredygtighed (VSB), April 2014. Nuuk: Departementet for Ehrverv, Råstoffer og Arbejdsmarked, Naalakkersuisut/Grønlands Selvstyre.

36. Sara Bjørn Aaen, Demokratisk legitimitet i høringsprocesser i forbindelse med storskala-projekter i Grønland (Nuuk: Grønlands Arbejdsgiverforening, 2012).

37. London Mining. http://www.londonmining.com (accessed June 26, 2014).

39. Report to Inatsisartut on Mineral Resource Activities in 2013: Annual Report 2013, op. cit.

41. Tim Boersma and Kevin Foley, op. cit., 47.

42. Social Impact Assessment for the ISUA Iron Ore Project for London Mining Greenland A/S (in compliance with the BMP Guidelines on SIA of November 2009) Final Report (March 2013). http://www.naalakkersuisut.gl/~/media/Nanoq/Files/ (accessed July 31, 2014).

46. Mark Nuttall, “The Isukasia iron ore mine controversy: Extractive industries and public consultation in Greenland,” Nordia Geographical Publications Yearbook 41, no. 5 (2012): 28.

48. Mark Nuttall, op. cit., 29.

49. Mark Nuttall, op. cit., 31.

50. Press releases from London Mining. http://www.londonmining.com (accessed October 16, 2014).

51. See http://naalakkersuisut.gl/en/Naalakkersuisut/News/2015/01/080115-London-Mining (accessed October 26, 2015).

52. Report to Inatsisartut on Mineral Resource Activities in 2013: Annual Report 2013, op. cit.

53. Tim Boersma and Kevin Foley, op. cit., 27.

54. http://www.tanbreez.com/en/

56. Tanbreez Local Use Study, August 2013, http://www.tanbreez.com/media/1444/5 (accessed July 31, 2014).

57. http://www.tanbreez.com/media

58. http://www.tanbreez.com/en/

59. http://naalakkersuisut.gl/da/Høringer/Arkiv-over-høringer/2013/Tanbreez (accessed October 21, 2014).

60. http://www.tanbreez.com/en/news/

61. Sara Bjørn Aaen, op. cit., 89–90.

Ackrén, Maria and Bjarne Lindström. “Autonomy Development, Irredentism and Secessionism in a Nordic Context.” Commonwealth & Comparative Politics 50, no. 4 (2012): 494–511.

Bengtsson, Åsa. Politiskt deltagande (Sverige: Studentlitteratur, 2008), 50–1.

Bjørn Aaen, Sara. Demokratisk legitimitet i høringsprocesser i forbindelse med storskala-projekter i Grønland (Nuuk: Grønlands Arbejdsgiverforening, 2012).

Boersma, Tim and Kevin Foley. “The Greenland Gold Rush: Promise and Pitfalls of Greenland’s Energy and Mineral Resources.” In John L. Thornton China Center and the Energy Security Initiative (Washington, New York: Brookings, 2014), vi.

Greenland Parliament Act of 7 December 2009 on mineral resources and mineral resource activities (the Mineral Resources Act). http://www.govmin.gl/images/stories/faelles/mineral_resources_act_unofficial_translation.pdf

Guidelines for Social Impact Assessments for Mining Projects in Greenland. https://www.govmin.gl/images/stories/minerals/sia_guideline/sia_guidelines.pdf (accessed February 20, 2016).

Hansen, Anne Merrild and Lone Kørnøv. “A Value-Rational View of Impact Assessment of Mega Industry in a Greenland Planning and Policy Context.” Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal 28, no. 2 (2010): 135–45.

Hansen, Klaus Georg. “Greenlandic Perspectives on Offshore Oil and Gas Activities – An Illustration of Changes in Legitimacy Related to Democratic Decision Processes.” Journal of Rural and Community Development 9, no. 1 (2014): 134–54.

Jackson, Robert J. and Doreen Jackson. Contemporary Government and Politics: Democracy and Authoritarianism (Scarborough, Ontario: Prentice Hall Canada Inc., 1993).

Jones, Martin, Rhys Jones, and Michael Woods. An Introduction to Political Geography: Space, Place and Politics (London: Routledge, 2004).

List of Mineral and Petroleum Licenses in Greenland. https://www.govmin.gl/images/list_of_licences__20160216.pdf (accessed February 18, 2016).

London Mining. http://www.londonmining.com (accessed June 26, 2014).

Lov om Grønlands Selvstyre, nr. 473, Lovtidende A 2009, udgivet den 13. juni 2009.

Memorandum of Understanding between the Ministry of Mineral Resources of Greenland and the National Energy Board of Canada Regarding Cooperation. https://www.neb-one.gc.ca/bts/ctrg/mmrndm/2015-07-31mnstrmnrlrsrc-eng.html (accessed February 18, 2016).

Mortensen, Bent Ole Gram. “The Quest for Resources – The Case of Greenland.” Journal of Military and Strategic Studies 15, no. 2 (2013): 93–128.

Nuttall, Mark. “The Isukasia Iron Ore Mine Controversy: Extractive Industries and Public Consultation in Greenland.” Nordia Geographical Publications Yearbook 41, no. 5 (2012): 23–34.

Nuttall, Mark. “Zero-Tolerance, Uranium and Greenland’s Mining Future.” The Polar Journal 3, no. 2 (2013): 368–83.

Olsen, Anna-Sofie H. and Anne Merrild Hansen. “Perceptions of Public Participation in Impact Assessment: A Study of Offshore Oil Exploration in Greenland.” Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal 32, no. 1 (2014): 72–80.

Pelaudeix, Cécile. “Governance of Arctic Offshore Oil & Gas Activities: Multilevel Governance & Legal Pluralism at Stake.” In Arctic Yearbook 2015, ed. Lassi Heininen et al. (Akureyri: Iceland, Northern Research Forum, 2015), 214–33.

Report to Inatsisartut on Mineral Resource Activities in 2013: Annual Report 2013, Naalakkersuisut – Government of Greenland. http://www.govmin.gl/images/stories/about_bmp/publications/R%C3%A5stofredeg%C3%B8relse UK 28-februar 2014.pdf

Shively, W. Phillips. Power & Choice: An Introduction to Political Science. 4th ed. (New York, USA: McGraw-Hill Inc., 1995).

Social Impact Assessment for the ISUA Iron Ore Project for London Mining Greenland A/S (in compliance with the BMP Guidelines on SIA of November 2009) Final Report (March 2013). http://www.naalakkersuisut.gl/~/media/Nanoq/Files/ (accessed July 31, 2014).

Tanbreez Local Use Study, August 2013. http://www.tanbreez.com/media/1444/5 (accessed July 31, 2014).

The Aarhus Convention. http://ec.europa.eu/environment/aarhus/ (accessed February 18, 2016).

The Mineral Resources Act. https://www.govmin.gl/images/stories/faelles/mineral_resources_act_unofficial_translation.pdf (accessed February 18, 2016).

Vurdering af Samfundsmæssig Bæredygtighed (VSB). (Nuuk: Departementet for Ehrverv, Råstoffer og Arbejdsmarked, Naalakkersuisut/Grønlands Selvstyre, 2014).

http://naalakkersuisut.gl/da/Høringer/Arkiv-over-høringer/2013/Tanbreez (accessed October 21, 2014).