1 Introduction

At the opening session of the Third International Arctic Forum “The Arctic—Territory of Dialogue” in 2013, Russian President Vladimir Putin boldly declared: “The Arctic is opening up a new page in our history, one that we may call the era of industrial breakthrough. Intensive development of new gas and oil fields is underway, large transport and energy facilities are being constructed, and the Northern Sea Route revived.”1 After a period of relative neglect, the Arctic is back on the official Russian agenda.2 The development of the country’s Arctic resource base is frequently presented as a key driver not only for the region itself, but for the Russian economy as a whole,3 with the Arctic portrayed as an icy treasure trove just waiting to be opened. Harking back to the Soviet “opening up” of the Arctic in the 1930s, Russian officials again talk about “mastering” (osvoenie) the Arctic; of how to harness and tame the country’s vast and inhospitable northern reaches along the Arctic coast.4

However, the authorities are also highly aware that the Arctic comes with a specific set of challenges related to climatic conditions, the weakly developed or non-existent infrastructure, and—beyond a few major urban settlements—an extremely sparse, dispersed population. There is widespread recognition that the state must take the lead in developing the Russian Arctic. To this end, and to ensure efficient policy implementation, in 2015 the government established the State Commission for Arctic Development,5 intended to serve as a platform for coordinating the execution of the government’s ambitious plans for the Arctic, for exchange of information and airing of concerns among various Arctic actors, and for dealing with interagency and interregional conflicts.

The Russian system of governance is frequently described as extremely centralized, organized along a strictly hierarchic “power vertical” (vertikal’ vlasti) with considerable hands-on, “manual” (ruchnoi) management by the Kremlin.6 At first glance, the State Commission for Arctic Development does not seem to fit this description: with a membership drawn from various sectors and levels of government, it looks more like a loose policy network7 than a link in a hierarchic chain of command. As such, the State Commission demonstrates how the Russian authorities are apparently trying to tackle some of the problems inherent in the executive structure, like the lack of horizontal interagency coordination, and the weak feedback loop/input flow from below.

Based on a case study of the State Commission for Arctic Development, this article has a twofold goal. First, we explore current Russian domestic Arctic politics: who do the authorities identify as the key actors? who have been recruited to serve on the State Commission? what topics/policy directions has the State Commission prioritized? and what results have been achieved? In short, what can the operations of the State Commission tell us about Russia’s domestic Arctic policy agenda?

Second, we discuss what this case study can say about policy formulation and implementation in today’s Russia and the challenges associated with providing effective and efficient institutions in the context of authoritarian modernization.8 By examining how domestic Arctic interests are pooled, discussed, and mediated in the State Commission, we seek to problematize the widespread image of a strictly hierarchic power vertical now operating in Russia.

2 Dissecting the vertical

As noted, the Russian system of governance is frequently depicted as based on a “power vertical,” a hierarchical “power pyramid” of top–down, centralized executive power, somewhat reminiscent of Soviet “democratic centralism.”9 The vertical is complemented by other (selectively) recirculated elements of the Soviet legacy, such as low elite circulation (“cadre stability”), a closed elite-recruitment process, state control over the major media outlets, and repression of dissent,10 forming the basis of what has been described as post-Soviet “patronal presidentialism.”11

In the course of Vladimir Putin’s years at the helm, Russia has undergone a fundamental and far-reaching re-centralization of politics and society.12 This warrants a focus on the signals and decisions emanating from the Kremlin. However, such a perspective can provide only part of the picture. Indeed, Putin remains the ultimate arbiter and moderator between competing elite groups13—but we must cast the net wider in order to account for the frequently contradictory outcomes characteristic of actual policy implementation.

First, there is a lack of coordination and a clear division of labor between various state structures. Despite all the talk about “the vertical,” the system remains dominated by blurred lines of responsibility and turf battles over policy areas. Differences in priorities continuously create friction and disagreement. Discussing the implementation of his 2012 May Decrees (maiiskie ukazy), Putin himself openly complained that he sometimes had “the impression that some agencies live in their own world, solely with their own narrowly defined problems, and lack any understanding of the common strategic tasks facing the country and the citizens, for whom we work.”14

Second, efficient implementation is hampered by a bloated bureaucracy. According to Andrew Monaghan, “the leadership has long faced serious problems in the implementation of its instructions—except through direct personal intervention of the most senior authorities themselves.”15 However, even when the Kremlin mobilizes behind a policy, there is no guarantee of success. Alena Ledeneva has described the debilitating power of the sistema, the informal “power networks that account for the failure to implement leaders’ political will.”16 Only by taking into account the conflicting interests and competing agendas involved in the implementation process can we explain the outcomes.

Finally, the hierarchy of the power vertical is far from an army-like chain of command. As noted by Vladimir Gel’man, according to the logic of the vertical, “virtually all instances of wrongdoing, misbehavior, and poor performance should require the threat of punishment.” However, “the systematic use of repression against lower level officials of the power vertical is relatively rare.”17 Notwithstanding the regime’s autocratic features, officials can generally get away with not fully adhering to or implementing instructions from the federal government.

Thus, Daniel Treisman proposes distinguishing between mundane day-to-day “normal politics” and instances of “manual control” (ruchnoe upravlenie). The latter refers to the cases in which Putin intervenes personally and the logic of the vertical kicks in; the former passes under the Kremlin radar and is characterized by “vicious competition between bureaucratic factions, business actors, regional elites, and powerful individuals.”18 Inspired by the work of Treisman, the present article employs a case study of the State Commission for Arctic Development to add to our understanding of Russian governance and the challenges entailed in providing effective and efficient institutions in the context of authoritarian modernization.

3 Where is the “Russian Arctic”?

Before examining the composition and work of the State Commission for Arctic Development, we need to define where and what the “Russian Arctic” is in this context. For decades, the Russian authorities, like the Soviet authorities before them, have struggled to define what territories to include in this category, as well as how to organize the development of this climatically challenging region.19 In the 1930s, in conjunction with ambitious plans for “mastering” (osvoenie) the northern frontier, the authorities introduced a special regime for the “Far North” (Krainii sever): to attract the labor resources necessary to develop the region, the regime offered “Northern” benefits and compensation, such as higher wages and lower retirement age.20

Over the years, this was gradually extended not only in terms of benefits but also in geographic scope, with the border of the “Far North” being pushed further south as more regions were included in the “Northern” preference scheme.21 After the breakup of the Soviet Union, with the state on the brink of bankruptcy, the Far North regime faced collapse. Clearly, the Soviet approach would have to be fundamentally revised.22 However, it took more than two decades, extended debates, and several failed attempts before the government in 2014 came up with a new geographic definition, shrinking the overstretched “Far North” back to a more focused “Arctic Zone of the Russian Federation”.23

Rather than relying on the Arctic Circle or a definition based on isotherms24 or the tree-line, Russian authorities took the existing administrative borders as their point of departure.25 Currently, nine federal subjects are fully or partly included in the Arctic Zone (in addition to the islands under Russian jurisdiction in the Arctic Ocean) (see Table 1). We apply this definition here—with its subsequent amendments in form of territorial adjustments—in discussing the development of Russia’s domestic Arctic policies.

| Federal subjects fully included | Federal subjects partly included |

|---|---|

| Murmansk | Republic of Karelia: 3 municipalities* |

| Chukotka Autonomous Okrug | Komi Republic: Vorkuta city |

| Nenets Autonomous Okrug | Sakha Republic: 13 municipalities** |

| Yamal-Nenets Autonomous Okrug | Arkhangelsk: 7 municipalities*** |

| Krasnoyarsk: Norilsk city and 2 municipalities |

* Added by Presidential Decree in June 2017.

** Originally five; another eight were added by Presidential Decree in May 2019.

*** This includes six municipalities on the mainland plus the Novaya Zemlya archipelago.

After the most recent enlargement, the Arctic Zone now covers an area of approximately 4.9 million km2—or almost 29% of the total territory of the Russian Federation.26 Besides a few major cities, however, the territory is extremely sparsely populated: an estimated 2.4 million (1.7% of the total population of the Russian Federation)—and this in decline. In several of the regions included in the Arctic Zone, population density is below 0.05 persons per km2.27

What traditionally has put the Arctic on the domestic policy agenda is the region’s abundant natural resources. Various figures have been bandied about as regards the Arctic resource base. According to one attempt at taking stock of the current level of resource exploitation, more than 80% of Russian gas extraction takes place in the Arctic Zone, and 90% of the mining of nickel and cobalt, 60% of copper, and 96% of platinum.28 There is, however, still a lack of statistical data specifically on the Arctic Zone; experts and politicians alike generally present an “Arctic” resource base involving a territory much larger than the current official Arctic Zone.29 For decades, the Arctic has also played a key role in Soviet and Russian military strategy, with Murmansk as the home base of the Northern Fleet, Russia’s strategic nuclear fleet.30 More recently, the revival of the Northern Sea Route (NSR) as a major transport artery has become a national priority.31 Developing the Arctic is therefore of vital importance to Russia.

4 Who are the Arctic actors?

Turning to the State Composition for Arctic Development as a potential hub for coordinating the implementation of the government’s ambitious plans for the Arctic, what actors and stakeholders do the authorities themselves acknowledge as key in the development of the Russian Arctic? To explore this, we examine who was included in the State Commission as well as membership dynamics over time. The State Commission was officially established in March 2015.32 On its webpages it is described as

… a coordinating body ensuring the interaction of federal executive authorities, executive authorities of the constituent entities of the Russian Federation, other state bodies, local governments, and organizations in solving socio-economic and other tasks related to the development of the Arctic Zone of the Russian Federation and ensuring national security.33

Initially, the Commission was headed by Deputy Prime Minister Dmitrii Rogozin, who also coordinated the Arctic portfolio in the federal government (in addition to overseeing the military-industrial complex). After Rogozin’s dismissal in May 2018,34 the State Commission had no leader and remained inactive for several months until December 2018, when it was revamped and relaunched under new leadership: Yurii Trutnev, Deputy Prime Minister and Presidential Plenipotentiary to the Far Eastern Federal Okrug. Trutnev thus has responsibility for regional development in Russia’s entire far northern and eastern peripheries, a territory stretching from the border with Norway in the west to Vladivostok in the Russian Far East.35

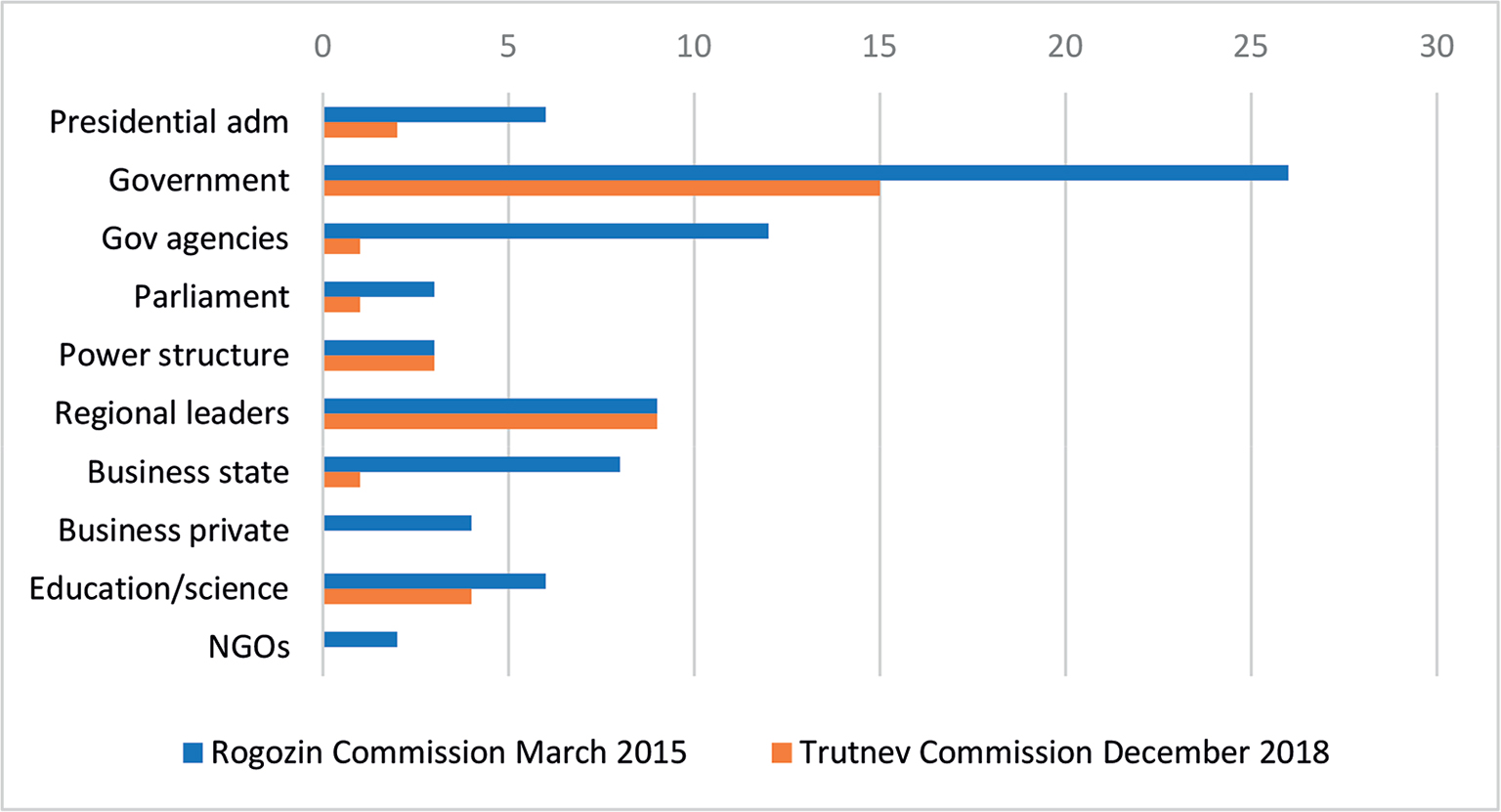

In Figure 1, membership in the Commission in 2015 and 2018, respectively, is broken down according to the main categories of institutional/sectoral affiliation. What immediately becomes clear is that, with the shift from Rogozin to Trutnev, the State Commission became a smaller, leaner body: the initial version in 2015 had a total of 79 members—and kept growing until Rogozin’s dismissal—as against Trutnev’s Commission with only 36.

4.1 Presidential Administration

The Presidential Administration is the central hub that stakes out the main directions of Russian policy, domestically as well as internationally. President Putin himself has taken a keen interest in Arctic developments, not least the revitalization of the NSR.37 Hence, it is somewhat surprising to note the virtual absence of the Presidential Administration in the current, revamped version of the State Commission: whereas there had been six members categorized as representing the “Presidential Administration” in the Rogozin Commission, now there are only two (see Fig. 1).

The reason is that the presidential plenipotentiaries, the Presidential Administration’s regional representatives to the federal districts, have been cut out of the loop. One of Putin’s early administrative reforms, aimed at reeling back some of the power that strong-willed regional leaders had amassed in the 1990s, regrouped all federal subjects into new macro-regions where presidential plenipotentiaries exercised an oversight function.38 The Arctic Zone cuts across four such federal districts—the Northwestern, Ural, Siberian and Far Eastern; under Rogozin, all four were represented in the Commission.39 In the new, leaner version of the Commission, however, they were for some reason no longer deemed relevant and were left out—the exception being Trutnev himself, doubling as Deputy Prime Minister and the plenipotentiary to the Far Eastern Federal District.40

The sole holdover from the Rogozin Commission (except for Trutnev) is Putin’s Special Representative to International Cooperation in the Arctic and Antarctica, Artur Chilingarov, the grand old man of Russian Arctic science—and the figure behind the infamous 2007 Russian flag-planting on the seabed under the North Pole. Chilingarov has been a central player in pushing the Arctic agenda for years, combining the role of prominent scientist and politician: he has served in State Duma 1993–2011 (representing Nenets Autonomous Okrug), the Federation Council 2011–2014 (representing Tula Oblast) and then returning to the State Duma from 2016 on the United Russia ticket.41

Despite this reduction, there has been an apparent upgrade in the representation of the Presidential Administration itself: In 2015, it was represented by Presidential Aide, Igor Levitin, a former Minister of Transport. In 2018, he was replaced by one of the current heavy-weights in the administration, First Deputy Head of the Presidential Administration, Sergei Kirienko, a former Prime Minister (1998) and Head of Rosatom (2005–2016). Strength is not only a matter of numbers: delegating Kirienko to the Commission also signals prioritization.

4.2 Government

Nevertheless, the backbone of the State Commission remains the federal government. In Rogozin’s Commission, there were no less than 26 representatives of various ministries (not counting persons representing federal agencies and services, see below); in the Trutnev Commission, there are 15. In 2015, in addition to Rogozin and one deputy prime minister, there were 10 ministers and 11 deputy ministers involved in the work of the Commission—at a time when were 22 federal ministries altogether. For all practical purposes, all ministries were represented (except, understandably, the ministries for the development of Crimea and for the development of the Northern Caucasus).

In Trutnev’s 2018 version of the Commission, there were only two ministers left: Dmitrii Kobylkin, Minister of Natural Resources and Ecology, and Aleksandr Kozlov, Minister for Development of the Far East. While the Far East covers the easternmost part of the Arctic Zone, in February 2019 Kozlov’s ministerial portfolio was actually expanded to include the whole of the Arctic (in geographical terms, his area of responsibility now overlaps with Trutnev’s). An additional ten ministries were represented by deputy ministers. Among the ministries no longer included are some of the “power ministries”—the Ministry of Internal Affairs and the Ministry of Justice—as well as several ministries representing the social bloc—the Ministry of Healthcare, the Ministry of Labor and Social Protection, and the Ministry of Construction, Housing and Utilities. In the Trutnev Commission there is thus a more narrow focus on Arctic development. The key role of natural resource exploitation for the future development of the Russian Arctic is signaled by the fact that the Ministry of Natural Resources is the only federal ministry represented by both the minister and a deputy minister (under both Rogozin and Trutnev).

4.3 Government agencies

In addition to the broad representation of the federal government itself, Rogozin’s Commission was also heavily populated by representatives of various federal agencies and services—in 2015, with 12 people, this was the second single biggest group. The agencies they represented spanned widely: from the Federal Space Agency and the Federal Agency for the Development of the State Border Infrastructure to the Federal Migration Service and the Federal Agency for Tourism.

Also here, Trutnev cut back hard, refocusing the composition of the Commission. Even in the prioritized sector of exploitation and management of Arctic natural resources, the Federal Service for Supervision of Natural Resources and the Federal Agency for Water Resources were now deemed superfluous: the only agency left in the 2018 version of the State Commission was the Federal Service for Hydrometeorology and Environmental Monitoring, represented by its head, Maksim Yakovenko.

4.4 Power structures

In view of the emphasis in the literature on the role of the siloviki, individuals with backgrounds from the “power structures”—the armed forces, security agencies, and similar entities—in the power vertical,42 it seems odd that this category is not very visible in the Commission. This is all the more surprising given the strategic importance of the Arctic and the explicit reference to national security in the mandate of the Commission. In the Rogozin Commission—beyond the siloviki listed under “government,” primarily the deputy ministers of defense, internal affairs, and emergency situations—there were only three such siloviki-dominated structures in evidence: the Security Council, represented by its Deputy Secretary, Vladimir Nazarov; the FSB, by the Head of the Economic Security Service, Yurii Yakovlev; and the Federal Drug Control Service by First Deputy Director Vladimir Kalanda.

In Trutnev’s Commission, the set-up has remained basically the same. The Security Council, reflecting this body’s key role in coordinating policy, now has two members in the Commission: the above-mentioned Nazarov, now as advisor to the Secretary of the Security Council, accompanied by a new Deputy Secretary, Sergei Vakhrukov. The third slot is occupied by the new Head of the Economic Security Service of the FSB, Sergei Korolev.

4.5 Parliament

In sharp contrast to the executive, the legislative branch has played a marginal role under both Rogozin and Trutnev. In 2015, there were two members from the State Duma: Mikhail Slipenchuk, Deputy Head of the State Duma Committee on Natural Resources, Environmental Management and Ecology; and Vitalii Yuzhilin, from the Committee on Budget and Taxes—none of which represented “Arctic” constituencies.43 From the Federation Council, there was only one: Vyacheslav Shtyrov, who represented the Republic of Sakha in the upper chamber (this position was seen as a form of “honorable retirement” of this former president of the republic, 2002–2010).

In the revamped Commission, as with the Presidential Administration, there was less, but apparently more influential, representation: the sole member from the Federal Assembly is Olga Epifanova, a Deputy Chair of the State Duma. Epifanova had been elected to the Duma on the ticket of A Just Russia as the top candidate on the regional sub-list for Arkhangelsk, Nenets, Komi, and Yamal-Nenets, and thus has the right “Arctic” credentials.44 However, as a member of the systemic opposition, she may carry less weight than a representative of Putin’s United Russia would have in a similar position.

As noted, Artur Chilingarov has a long and distinguished career in the Federal Assembly. By the time the Trutnev Commission was appointed, he was back in the State Duma, elected on the regional list of United Russia from Siberia (Krasnoyarsk, Khakassia, and Tyva).45 He could therefore have been included under the heading “parliament,” but in the official list of Commission members, it is his role within the executive that is highlighted, so in Figure 1 he is counted as a representative of that category.

4.6 State-owned and private businesses

Figure 1 also shows that business was well represented in Rogozin’s Commission, both through state-owned and private companies. All the energy majors—Gazprom, Rosneft, Lukoil, and Novatek—were represented by their CEOs or other members of the top management, as was Transneft, the state-owned oil pipeline monopoly. Also transport infrastructure was included, with Russian Railways, Sovcomflot (the state-owned shipping company specializing in shipping petroleum and LNG) and Atomflot (operator of Russia’s nuclear icebreaker fleet).

It seems surprising, then, given the emphasis in official strategies on developing the Arctic through public–private partnership,46 to note the absence of business actors in the revamped Commission. Gone are the oil and gas companies. Likewise, despite the ambitious plans to build railway lines connecting the Arctic better with the rest of the country—like the Northern Latitudinal Railway (Severnyi shirotnyi khod), intended to link the Northern and Sverdlovsk railways and eventually provide access to the NSR via Sabetta—Russian Railways is no longer included.47

Tellingly, the one commercial actor left is the state atomic energy corporation Rosatom, represented by Vyacheslav Ruksha, Director General of Rosatom’s newly established Northern Sea Route Directorate. After a protracted and bitter struggle for control over the NSR, new legislation adopted in December 2018 transferred the administration of the NSR from the Ministry of Transport to Rosatom.48 Henceforth, Rosatom will be in charge of development and operational responsibilities for shipping along the NSR, as well as infrastructure and seaports along the northern coast, and is thus destined to become a key Arctic player in the years to come.

4.7 Regional leaders

The local voice of the Arctic region is represented by regional heads of executive power. In both versions of the Commission, the number of regional representatives has been nine, the main difference being that Kamchatka, which according to the current definition is not an Arctic region, is no longer included. Instead Karelia, which, as noted above, had three municipalities added to the Arctic Zone in 2017 and is therefore now an “Arctic” region, is represented in the Commission.

However, the stable numbers mask a considerable turnover. In recent years, the Kremlin has been overhauling the gubernatorial corps, and the northern regions have not been spared. Only three of the original members—Marina Kovtun in Murmansk,49 Igor Orlov in Arkhangelsk and Roman Kopin in Chukotka Autonomous Okrug—were still in office when the new Commission was formed. The head of the Komi Republic, Vyacheslav Gaizer, had been arrested on suspicion of large-scale corruption,50 Dmitrii Kobylkin in Yamal-Nenets had been promoted to Minister of Natural Resources (thus, still a member of the State Commission, but now in a new capacity) while the heads of Nenets, Yamal-Nenets, Sakha, and Krasnoyarsk had all stepped down “voluntarily.”51

4.8 Others

Finally, there were several members recruited from science and education as well as from the NGO sector. In the Rogozin Commission there were six representatives of research and education: the rector of the State Polar Academy in St Petersburg,52 the director of the Far Eastern Geological Institute under the Academy of Sciences in Vladivostok, the director of the Zubov State Oceanographic Institute in Moscow, and the director of the Murmansk Marine Biology Institute, as well as directors of the Institute for National Strategy and the Russian Foundation for Advanced Research Projects in the Defense Industry. The NGO sector was represented by the Association of Polar Explorers53 and the business association Business Russia.

In the 2018 Commission, there were no NGO representatives at all. From academia, there were four: the deputy president of the Russian Academy of Sciences, the rector of the Bauman Moscow State Technical University, the rector of the Moscow Institute for Physics and Technology, and the head of the Department of Environmental Management of the Faculty of Geography of the Moscow State University. While the first three seem to confirm the trend of “fewer, but higher placed” representatives witnessed in some of the other categories of representatives, the fourth might seem an odd man out. However, the departmental head from the Moscow State University is the same Mikhail Slipenchuk who represented the State Duma in Rogozin’s Commission.

4.9 Continuity and change

A few people like Slipenchuk thus turn up in new capacities: Kobylkin had gone from being a governor to heading the Ministry of Natural Resources and Ecology, Nazarov had a new position within the Security Council, etc.—what might be taken as an indication of a nascent Arctic policy network. Overall, though, the turnover from the Rogozin Commission to the new Trutnev Commission was dramatic: out of the 79 original members, only 12 were included in 2018. Of these, only eight still held the same positions as in 2015.

Cutting the membership by more than half meant that many institutional actors were no longer included in 2018. And yet, among the 36 members of the Trutnev Commission, very few represented new institutions. In fact, 20 of the seats were filled by exactly the same positions as in 2015—indicating that these were to some extent reserved for ex officio representation. Another ten places went to people from structures/organizations that had been represented in 2015, but were represented at another level (typically, a federal minister now being replaced by a deputy minister). Although turnover has been high among the persons populating the Russian Arctic policy network, there seems to be more consensus on which institutional voices naturally belong within this group—the only “new” institutions/actors represented being the Republic Karelia and the four representatives from academia.54

As to sectoral representation, the dominance of the federal government has continued to grow (see Fig. 1): in Rogozin’s Commission, ministers and deputy ministers constituted the biggest single category by far, with government representatives making up 33% of the Commission’s membership. Despite the reduction in absolute numbers from 26 to 15 in the Trutnev Commission, the relative share of government representatives nevertheless increased, to 42%.

Also the regional executives have strengthened their relative share; they now form the second largest subgroup, with 25% of the seats (against 11% in 2015). However, given their dependence on the Kremlin, these regional executives remain severely circumscribed in their ability to stand up for regional interests.

With state agencies and business interests almost completely out of the picture, the third biggest group in 2018 became science and education with four seats, or 11%. However, none of the original six representatives of this sector were now on the Commission—nor were any of the six institutions/organizations they had represented.

Overall, we find an extreme turnover in representatives, but not to the same extent in the institutions represented. However, the initial goal of wide-ranging inclusion of various Arctic actors into the process of policy formulation has seemingly been abandoned, transforming the State Commission from a broad policy network to a more traditional state-dominated structure.

5 What is on the Arctic agenda?

As to the State Commission’s agenda, according to the 2015 decree, the Commission is to coordinate all things Arctic: its mandate ranges from adopting measures to improve the living standard of Arctic indigenous populations, to enabling “a favorable operational regime” for the armed forces, and to facilitating bi- and multilateral cooperation with the other Arctic states.55 To gauge what priorities the State Commission set for its work during the first four years of its existence, we go beyond official declarations56 and focus on what emerge as prioritized areas in texts published on the current and archived version of the Commission’s webpage.57

What appears to be the Commission’s main priority is the “maritime cluster”: issues related to the Northern Sea Route, shipbuilding (icebreakers), and port infrastructure. Exploiting the potential of the NSR as a national and international transportation artery has been a main driver of Russia’s Arctic policy in recent years. This shipping lane was developed during the Soviet period, but the infrastructure had largely fallen into disrepair by the early 2000s. At its peak, the NSR had had a cargo volume of about 6.5 million tons annually, but this had plummeted to 1.6 million tons by 1999, with the eastern stretches in particular having negligible volumes of freight.58

In the deliberations of the State Commission the NSR has been a recurrent theme. The tasks are formidable—in 2017 Rogozin mildly reproved the members of the Commission, reminding them that, despite the volumes having hit a record level the previous year, with the current forecasts, “the number of problems, issues, and tasks that we will have to solve will grow. Therefore, it is important for everyone to actively engage in the work, not keep dangling in the tail (boltat’sia v khvoste).”59

Without the necessary investment in infrastructure and logistics, the NSR cannot be competitive, Rogozin warned at a joint meeting of the State Commission and the Marine Board in December 2015. The sea lane would run the risk of remaining primarily a national transport artery, supplying Russia’s Arctic settlements and facilitating export of its natural resources (that is, intra- and destination shipping), but without tapping into the potentially lucrative international transit market.60 The same message was repeated by Trutnev at a March 2019 meeting with the State Commission’s presidium. Here he highlighted the work staked out for the State Commission in order to achieve President Putin’s ambitious target of increasing cargo volumes to 80 million tons by 2024:61 the need for further developing port capacities, providing the NSR with adequate search and rescue capacities, high-quality navigation, and medical support, as well as finding how to reduce the cost of icebreaker escort. Only then, according to Trutnev, “can we hope not only for the transportation of goods from our own investment projects, but also for transit.”62

The exploitation of natural resources has been another prominent topic on the State Commission’s agenda, primarily in the form of discussions of prioritized projects and plans for a comprehensive development (kompleksnoe razvitie) of the Arctic.63 Resource extraction is to form the backbone of Arctic development—this has been the key message ever since the formulation of the 2008 Basic Principles for Russia’s Arctic policy.64 So far, the main breakthrough has been the development of the Yamal Peninsula gas fields and the construction of a new port in Sabetta (opened in 2017) for shipment of LNG from Yamal.65

The State Commission has favored a development strategy for the Arctic centered on development clusters or “pillar zones” (opornye zony)—comprehensive investment projects intended to generate growth in the wider region.66 This model was introduced in response to what was seen as the failure of the government’s sector approach to Arctic development, and served as the linchpin of the 2017 revised version of the State Program.67

The main challenge has been to obtain the necessary funding for developing these projects at a time when the Russian economy is performing sluggishly. Initial plans for lavish state spending have had to be cut back, as the government has been forced into difficult prioritizations against the backdrop of declining revenues.68 Thus, a main focus of the Commission under Trutnev’s leadership has been public–private partnerships69 and pushing through a new investment regime with generous tax breaks/exemptions for companies wishing to invest in resource exploitation in the Arctic Zone (hydrocarbons in particular).70 As this new investment regime is meant to cover the whole Arctic Zone, it comes on top of attempts to promote the somewhat more narrowly defined pillar zones.

Analysis of the texts posted on the Commission’s websites also reveals a third priority area: the social sphere. Although there are some centers of growth and prosperity, overall the Arctic Zone is characterized by outmigration and below-average living standards. As Trutnev reported in April 2019, in 16 out of 23 entities included in the Arctic Zone, life expectancy is lower than the national average; in 15 out of 23, the share of dilapidated or uninhabitable housing is higher than the Russian average.71 In an interview with Rossiiskaya gazeta in the run-up to the 2017 Arctic Forum in Arkhangelsk, Rogozin declared:

Residents in the Russian Arctic should be confident in their economic and social future, they should not be detached from the cultural, social, and public life of the rest of the country. (…) They must be sure, for example, of being able to get to the district center all year round, and not just via the winter road. And that travelling to Moscow, St Petersburg, Vladivostok or any other city is not equivalent, in cost and time, to travelling to outer space.72

In the State Commission’s session in conjunction with the 2017 Arctic Forum, Rogozin stressed how he “more than once” had underlined that it is “important not only to consider the Arctic as a strategically important resource region, but also to acknowledge the specific problems and concerns of the people living and working there.”73 As noted, since 2018, some of the federal ministries in the “social bloc” are no longer represented in the Commission. However, that does not seem to imply that the social sphere is de-prioritized. On the contrary, at a meeting of the Commission’s presidium in April 2019, Trutnev stressed the need to look beyond the NSR and projects related to natural resource extraction:

The development of the Arctic Zone cannot be considered only as the development of the Northern Sea Route or the creation of conditions for the implementation of investment projects. The development of the region itself, the improvement of people’s living standards is of fundamental importance.74

Trutnev’s statement, made on the margins of the 2019 St Petersburg Arctic Forum, should be seen in light of President Putin’s address to that forum. Here he called for all Russian Arctic regions to be brought “at least to the level of the national average in key socioeconomic indicators and living standards,” indicating that this goal should be formalized in the new Arctic Strategy.75 The latter, scheduled for adoption by the end of 2019, will stake out the priorities for Russia’s Arctic policy toward 2035.

Other frequent Commission topics include technological development, environmental issues, and education/training of Arctic specialists. Conspicuously absent on the Commission’s websites is, oddly enough, the security dimension of Arctic politics. Given the prominence in public debate accorded to the question of the potential militarization of the Arctic, as well as the role envisioned for the State Commission in the security sphere,76 comments and discussion of security-related issues seem remarkably few and far between.77 In the context of the Commission’s work, even the otherwise hawkish Rogozin repeatedly referred to the Arctic as a zone of peace and cooperation, even after Crimea and the subsequent deterioration of Russia’s relations with the West.78

6 What are the results?

As noted, a recurrent problem in Russian governance is the low quality of implementation of adopted policies. When in April 2014 Putin called for the creation of a new Arctic body, he specifically underlined the need for better coordination across sectors and between levels in the Russian Arctic:

[I]t is necessary to improve the quality of public administration and decision-making—to this end, to create a single center of responsibility for the implementation of Arctic policy. I want to emphasize that we do not need a bulky bureaucratic body, but a flexible, efficiently operating structure that will help to better coordinate the activities of ministries and departments, regions, and business. It may be advisable to create a body similar in its status to a state commission with broad powers.79

But to what extent has the State Commission managed to coordinate Arctic interests and translate its priorities into specific policies and results? While we are fast approaching the end of the timespan that the 2013 Strategy for the Development of the Arctic Zone was meant to cover (2013–2020), much work still remains to be done in this sphere.

6.1 Weak representation of the Arctic voice

One priority of 2013 Strategy was to improve the coordination among governmental bodies at all levels. On paper, the State Commission looks like an ideal platform for pooling and coordination of Arctic interests, providing the “Arctic” governors with an important lobbying venue. The repertoire of regional lobbying has changed in recent years. In the 1990s, regional heads of executive power could threaten with withholding taxes, or in more extreme cases, secessionism, as a bargaining chip in their negotiations with the federal center.80 However, since the onset of Putin’s recentralization drive in the early 2000s, with the Kremlin assuming control over the appointment and dismissal of governors,81 regional heads have had to develop new approaches for seeking federal funding and backing for local priorities. Being represented in the State Commission gives regional leaders direct access to an arena where major state priorities concerning the Arctic are discussed and negotiated—and, in today’s federal bargaining process, such access to federal decision-makers is indeed a key resource.82

However, in lobbying the federal center, the heads of executive power in the Arctic Zone appear to have stuck to the traditional pattern of prioritizing the cultivation of bilateral ties with Moscow: all attempts at forming a coherent cross-regional “Arctic lobby” have failed;83 instead, the federal subjects compete with each other in courting the federal center.84 For example, in promoting regional plans for creating pillar zones—the Commission’s preferred mechanism for creating cluster-based economic growth in the Russian Arctic—the regional heads have been pushing their local infrastructure projects on Moscow, apparently with scant consideration for what their neighbors have in mind.85

Moreover, there are clear limits to the extent to which the regional voice has been allowed access. With the Kremlin’s current practice of “parachuting in” persons with weak or no regional ties to head the regional executive,86 the regional leaders may end up being more dependent on the federal center than on the regional electorate. And although the State Commission was explicitly mandated to ensure interaction with the level of local self-government in solving socio-economic problems,87 that level has not been represented in the Commission at all. Beyond the heads of the regional executive, other regionally based interests have not been granted representation: there has not been room for the regional legislatures, regional interest groups, or, indeed, the indigenous peoples of the Arctic.88 This has reduced the value of the Commission as a potential channel for providing feedback and inputs from the regional level into federal decision-making processes.

6.2 Mismatch between ambitions and resources

Another problem is the mismatch between the lofty goals put forward in the various strategies and programs, and the resources that have actually been mobilized. One example is the NSR. As noted, developing this transport artery comes across as the Commission’s key priority. The NSR has seen a steady rise in volumes in recent years, with more than a tripling of annual cargo volumes since 2015, reaching a record-high 18 million tons in 2018. However, the authorities still struggle to find the required funding and, importantly, the necessary cargo, to achieve Putin’s goal of an annual 80 million tons by 2024.89 The perhaps more realistic prognosis of the Government’s Analytical Center predicts a shortfall of up to 20 million tons.90

More than ten years after Moscow presented its plans for transforming the Arctic Zone into the “Russian Federation’s leading strategic resource base by 2020,”91 this ambition remains mainly a declaration of intent. The government’s targets for funding Arctic development through public–private partnership have not been met. Moreover, beyond large-scale priority projects like Yamal LNG, investments in other sectors (fishing, agriculture, the environment, telecommunications, tourism, and the social sphere) have remained limited.92

In addition, the new measures introduced to attract investment—the Arctic pillar zones (opornye zony)—duplicate other preferential regimes already in existence: they will have to compete with the long-established regime of “special economic zones” as well as the more recent “advanced special economic zones” (territorii operezhayushchego razvitiya) for private investment.93 These preferential regimes run the risk of simply cancelling each other out.

In general, Russia’s new Arctic policy, including the introduction of the State Commission itself, has been criticized for containing few original ideas and approaches. According to a leading Russian expert on domestic Arctic politics, Aleksandr Pilyasov, the shift from a sectoral approach to pillar zones promoted by the State Commission represented

… a return to the approaches that have been known to us since the 1930s. Already then [experts] spoke about integrated plants that combine both transport and production functions in one structure. (…) So the idea of pillar zones is a remake, or, as they like to say now, a project for mastering (osvoenie) the Arctic 2.0.94

In recent years, Russia has indeed channeled considerable resources aimed at re-establishing a military presence along the Arctic coast and developing Yamal LNG. However, the Arctic in general continues to suffer from accumulated underinvestment in infrastructure and development of its unique resource base.

6.3 Lack of implementation

Finally, this survey of the State Commission’s activity should serve as a useful reminder of the challenges associated with attempts at authoritarian modernization in today’s Russia: there is often a long way to go from hammering out a policy at the federal level to its successful implementation in the regions. Despite the formal strict top–down organization of the executive structure, the adoption of a decree or a policy document is by no means a guarantee that this policy will actually be implemented by the relevant structures. The process towards realization may encounter considerable bureaucratic inertia, infighting, numerous detours and dead ends before eventually ending up in diluted form—or simply fizzling out.95 Taking stock toward the end of the first year of the State Commission’s operation, Rogozin openly complained of the difficulties in making headway: “Summing up the nine months of our joint work, I must admit that we are moving ahead much more slowly than originally planned.” One reason, he added, was that several instructions issued by the State Commission had either been not fully executed or not executed at all.96

In a similar update in December 2016, Rogozin stressed that, while one of the goals of the Commission’s activity was to “radically increase the efficiency of the state administration in the Arctic Zone,” proper results could not be achieved “without the responsible implementation of the decisions of the commission on part of the federal executive bodies.” However, he said, the decisions taken by the State Commission had often been nullified due to lack of due execution.97

Frustration at the lack of progress is reflected in the activity level of the State Commission itself—at least, judging by its own websites. During the first two years, the pages were updated fairly regularly, but from 2017 the frequency dropped, with new updates being few and far between.98 Also Prime Minister Dmitrii Medvedev was clearly dissatisfied with the Commission’s performance. Not only did he fail to re-appoint Rogozin after Putin’s re-election in spring 2018—when announcing the re-launch of the State Commission in December that year, he stated, with poorly disguised criticism, that the new commission would be “more compact” and “businesslike,” and that “its work should be more intensive, given the scale of the tasks.”99

At the annual “Arctic: Present and Future” Conference in St Petersburg in December 2018, Sergei Vakhrukov, Deputy Secretary of the Security Council, and soon to be appointed member of the revamped State Commission, complained that under Rogozin the State Commission had lacked real powers, making the effect of its activities “almost zero.”100 Vakhrukov argued the need for creating a new state body for the development of the Arctic and the NSR. The more high-profile membership in the Trutnev Commission may be seen as a partial response to this lack of authority and apparent breakthroughs.

However, problems persisted. In January 2019, not much more than a month after Medvedev had presented the revamped commission, Medvedev complained to Putin about the State Commission just “meeting on a case-by-case basis,” and the government lacking a permanent, unified structure for coordinating Arctic activity.101 The answer, Medvedev suggested, was to transfer responsibility for coordination of the Arctic portfolio into the ministerial structure, establishing an Arctic division within the Ministry for the Development of the Far East. To reflect its new responsibilities, the ministry was renamed the Ministry for the Development of the Far East and the Arctic, with Deputy Minister Aleksandr Krutikov assuming responsibility for coordinating development of the Arctic Zone as well as the wider Arctic.102 With this move, much of the rationale for maintaining the State Commission disappeared—although it has not yet been abolished or restructured to reflect this change of priorities.

7 Concluding discussion: What does this tell us about Russian Arctic priorities—and about Russian governance?

Overall, the Russian government’s renewed focus on the Arctic Zone has yielded some impressive results. Despite the negative impact of Western sanctions on the economy, particularly on the development of the Arctic oil and gas sector, Yamal LNG and Sabetta are now up and running. Moreover, new icebreakers are being phased in, the NSR continues to set records in annual cargo turnover (although mostly from destination shipping); old Soviet airfields are being renovated; and a network of search and rescue centers is again operating along the NSR. The rationale behind establishing the State Commission for Arctic Development was to facilitate the further development of this region, bringing together various groups and actors with partly overlapping, partly conflicting interests, belonging to different networks, and representing a range of interests (state, corporate, social, etc.), but with a shared focus on the Arctic.

As we have seen, however, the performance of the State Commission has been lackluster, and concrete results of the Commission’s work have fallen short of the Kremlin’s expectations. The two chairs, first Rogozin and then Trutnev, have blamed this on the bureaucracy—they have repeatedly complained about the failure of various agencies to implement the Commission’s decisions. Medvedev and the government have tended to put the blame the Commission itself: it has been insufficiently hands-on, has met too seldom, and has failed to set the agenda.

The State Commission has also been accused of serving old wine in new bottles: While it has developed various initiatives for Arctic development, there has been an acute shortage of new ideas and approaches. For instance, the “pillar zones” promoted by the Commission represent a return to an approach to Arctic development that was tested already by the Soviet authorities. Moreover, the scheme for attracting private investment to these zones is simply another version of that applied in the existing “special economic zones” and “advanced special economic zones”: all are based on introducing various forms of tax breaks and preferential treatment for private investors. In addition, less than two years after the plans for pushing cluster-based economic development in the Arctic Zone were adopted, the State Commission partially undermined the main principles through presenting new plans for universal tax breaks for investors across the Arctic Zone.103

The lack of concrete results related to the Commission’s work may also indicate that the Arctic is less of a priority than the impression given by the media hype. Despite Putin’s personal involvement in pushing Arctic development—previously with a main focus on resource exploitation, now increasingly with an emphasis on the NSR—other, less high-profile but nevertheless crucial reforms have been discussed for years, without progressing very far. For one, the complex composition of the Arctic Zone with its mix of full federal subjects and sub-regional entities complicates administration significantly.104 However, various suggestions for dealing with this, for example through introducing an Arctic Federal Okrug, have gained little traction. Similarly, the idea of adopting a separate law on the Arctic Zone has been discussed for years.105 Such a law would aim at unifying and harmonizing the patchwork of the many pieces of legislation currently regulating the Arctic Zone. However, despite several initiatives, this work has hardly moved forward. Although we cannot necessarily infer from the extended hiatus in the operation of the State Commission in 2018 (between Rogozin stepping down and Trutnev taking up responsibility) a general lack of interest in the Arctic, this at least demonstrates that the work of the State Commission for Arctic Development has not topped the government’s agenda.

What can this case tell us the about policy formulation and implementation in today’s Russia more generally? Institutionally, the case demonstrates the struggle to create effective and efficient institutions in the context of authoritarian modernization.106 Overall, there seems to be an element of trial and error. The introduction of the State Commission for Arctic Development came after a long debate about the need for introducing a “Ministry for Arctic Development” similar to the ministries that had been established to secure funding and development for other prioritized regions (a Ministry for the Development of the Far East was established in 2012; for the North Caucasus, in 2014; and for Crimea, in 2014).107 Instead, the Kremlin opted for a state commission, a sort of hybrid that sat uneasily within the hierarchy of the vertical. In 2019 the experiment with a more network-based organization apparently came to an end. Although the Kremlin continued to resist establishing a separate ministry, the 2019 introduction of an Arctic portfolio in the Ministry for Development of the Far East meant that the State Commission for Arctic Development lost its position as the central arena for hammering out Russia’s Arctic policy, and that the Arctic, at least for the time being, had secured a more permanent “home” in the governmental apparatus.

Concerning policy implementation, our findings show that, rather than taking at face value the goals and ambitions expressed in official strategies and programs on the Arctic—which frequently have a certain declarative or even aspirational character108—or approaching the implementation of adopted policies as being carried out through a clearly defined chain of command, there has been a fair amount of what Treisman refers to as “normal politics” with its associated infighting and obstructionism.109 Even at the best of times, the Kremlin has struggled to get the far-flung Russian bureaucracy to implement its decisions. During Putin’s first two terms, for example, when Russia experienced an economic boom, experts and officials alike estimated that “Strategy 2010,” the Putin presidency’s program for the socio-economic development of the Russian Federation for 2000–2010, was implemented only 30%–40%.110 Our case study confirms that even with “manual” (ruchnoi) involvement from Putin himself, it can be difficult to achieve the desired goals. In the case of the State Commission, this led to a major re-vamping, shifting once again to a more top–down, statist approach.

Fotnoter

- 1 Vladimir Putin, “Vstuplenie na plenarnom zasedanii III Mezhdunarodnogo arkticheskogo foruma ‘Arktika – territoriya dialoga,” September 25, 2013. http://kremlin.ru/events/president/transcripts/19281.

- 2 In 2008, the government adopted the “Basic Principles for the Arctic Policy of the Russian Federation toward 2020 and Beyond” (“Osnovy gosudarstvennoi politiki Rossiiskoi Federatsii v Arktike na period do 2020 goda i dal’neishuyu perspektivu,” September 18, 2008. http://government.ru/info/18359/). In 2013, the process of Arctic policy formulation gained further momentum when, for the first time since the breakup of the Soviet Union, Russia adopted a strategy for the Arctic, outlining national interests in the region (“O Strategii razvitiya Arkticheskoi zony Rossiiskoi Federatsii i obespecheniya natsional’noi bezopasnosti na period do 2020 goda,” February 20, 2013. http://government.ru/info/18360). This was followed by the “State Program for the Socio-Economic Development of the Arctic Zone of the Russian Federation toward 2020” in 2014 (“Ob utverzhdenie gosudarstvennoi programmy o ‘Sotsial’no-ekonomicheskoe razvitie Arkticheskoi zony Rossiiskoi Federatsii na period do 2020 goda’,” April 21, 2014. http://government.ru/docs/11967/). The latter was revised in 2017 and extended to 2025 (“O novoi redaktsii gosudarstvennoi programmy ‘Sotsial’no-ekonomicheskoe razvitie Arkticheskoi zony Rossiiskoi Federatsii’,” August 31, 2017. http://government.ru/docs/29164/).

- 3 Heater A. Conley and Caroline Rohloff, The New Ice Curtain: Russia’s Strategic Reach to the Arctic (Washington, DC: CSIS, 2015), vii, see also Galina Mislivskaya, “Putin rasskazal o programme osvoeniya Arktiki,” Rossiiskaya gazeta, December 14, 2017. https://rg.ru/2017/12/14/putin-rasskazal-o-programme-osvoeniia-arktiki.html.

- 4 For discussion of the Soviet approach to Arctic development, see, e.g., Helge Blakkisrud, “What’s to be done with the North?” in Tackling Space: Federal Politics and the Russian North, Helge Blakkisrud and Geir Hønneland, eds. (Lanham, MD: University Press of America, 2005), 25–52; Marlene Laruelle, Russia’s Arctic Strategies and the Future of the Far North (Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, 2014); Maria L. Lagutina, Russia’s Arctic Policy in the Twenty-First Century (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2019).

- 5 “O Gosudarstvennoi komissii po voprosam razvitiya Arktiki,” March 14, 2015. http://government.ru/docs/17319/.

- 6 See, e.g., William E. Pomerantz, “President Medvedev and the Contested Constitutional Underpinnings of Russia’s Power Vertical,” Demokratizatsiya 17, no. 2 (2009): 179–192; Graeme Gill, “The Basis of Putin’s Power,” Russian Politics 1, no. 1 (2016): 46–69; Vladimir Gel’man, “The Vicious Circle of Post-Soviet Neopatrimonialism in Russia,” Post-Soviet Affairs 32, no. 5 (2016): 455–473.

- 7 Policy networks can be defined as “formal institutional and informal linkages between governmental and other actors structured around shared if endlessly negotiated beliefs and interests in public policy making and implementation” (Roderick Arthur William Rhodes, “Policy Network Analysis,” in The Oxford Handbook of Public Policy, Michael Moran, Martin Rein and Robert E. Goodin, eds. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006), 426.) For more on the operation of policy networks, see John Peterson, “Policy Networks,” in European Integration Theory, Antje Wiener and Thomas Diez, eds. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004), 117–135; Rhodes, “Policy Network Analysis.” On Russia as a network state, see Vadim Kononenko and Arkady Moshes, eds. Russia as a Network State: What Works in Russia When State Institutions Do Not? (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011); Sabine Kropp et al., eds. Governance in Russian Regions: A Policy Comparison (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018).

- 8 Vladimir Gel’man and Andrey Starodubtsev, “Opportunities and Constraints of Authoritarian Modernisation: Russian Policy Reforms in the 2000s,” Europe–Asia Studies 68, no. 1 (2016): 97–117.

- 9 Pomerantz, “President Medvedev;” Gill, “The Basis of Putin’s Power;” Gel’man, “The Vicious Circle.”

- 10 Vladimir Gel’man, “Bringing Actors Back In: Political Choices and Sources of Post-Soviet Regime Dynamics,” Post-Soviet Affairs 34, no. 5 (2018): 290.

- 11 Henry E. Hale, Patronal Politics: Eurasian Regime Dynamics in Comparative Perspective (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015).

- 12 See, e.g., Richard Sakwa, Russian Politics and Society (London: Routledge, 2008).

- 13 See, e.g., Richard Sakwa, Russia’s Futures (London: Polity Press, 2019).

- 14 “Prezidentu predstavleny plany raboty ministerstv po ispolneniyu maiskikh ukazov,” June 7, 2013. http://www.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/18277. For examples of how Putin and Medvedev have faced numerous problems with implementing their policies, see Andrew Monaghan, “The Vertikal: Power and Authority in Russia,” International Affairs 88, no. 1 (2012): 1–16; Andrew Monaghan, Defibrillating the Vertikal? Putin and the Russian Grand Strategy (London: Royal Institute of International Affairs, 2014).

- 15 Monaghan, Defibrillating the Vertikal?, 1.

- 16 Alena Ledeneva, Can Russia Modernise? Sistema, Power Networks and Informal Governance (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013), 4.

- 17 Gel’man, “The Vicious Circle,” 461.

- 18 Daniel Treisman, ed., The New Autocracy: Information, Politics, and Policy in Putin’s Russia (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press, 2018), 16.

- 19 Laruelle, Russia’s Arctic Strategies; Lagutina, Russia’s Arctic Policy.

- 20 Blakkisrud, “What’s to be done.”

- 21 Helmut Klüter, “Der Norden Russlands – vom Niedergang einer Entwicklungsregion,” Geographische Rundschau 52, no. 12 (2000): 12–20.

- 22 Blakkisrud, “What’s to be done.”

- 23 Ukaz Prezidenta No 296, “O sukhoputnykh territoriyakh Arkticheskoi zony Rossiiskoi Federatsii,” May 2, 2014. http://www.kremlin.ru/acts/bank/38377. Until quite recently, the term “Arctic” (Arktika) would primarily be used to refer to the Arctic Ocean and its shores, but in the 2000s it has increasingly replaced the “Far North” as the now preferred way of referring to the northern territories (Laruelle, Russia’s Arctic Strategies, 29).

- 24 “The Arctic” is often defined as territories where the average daily summer temperature does not rise above 10 degrees Celsius.

- 25 Mikhail Zhukov, “Metodologicheskie i metodicheskie problemy vydeleniya Arkticheskoi zony Rossiiskoi Federatsii,” Arktika XXI vek. Gumanitarnye nauki 1, no. 2 (2014): 4–20.

- 26 The 2019 enlargement with eight new regions (ulusy) in Sakha being added to the Arctic Zone increased the territory by more than 1 million km2.

- 27 See the interactive Arctic map developed by the European University in St Petersburg at http://www.interarctic.ru/map.

- 28 Igor Melamed et al., “Arkticheskaya zona Rossii v sotsial’no-ekonomicheskom razvitii strany,” Vlast’ no. 1 (2015): 6.

- 29 This critical lack of information is recognized in the 2017 revised version of the State Program, which calls for identifying the Arctic Zone as a separate unit for statistical data-collection (“O novoi redaktsii”). For estimates of the resource base, see, e.g., Mikhail Kamenetskii, “Prostranstvennoe osvoenie sukhoputnykh territorii Arkticheskoi zony RF kak sfera spetsializirovannoi deyatel’nosti stroitel’nogo kompleksa,” Nauchnye trudy: Institut narodnokhozyaistvennogo prognozirovaniya RAN no. 13 (2015): 402–417; Valerii Konyshev, Aleksander Sergunin and Lassi Heininen, “‘Global’naya Arktika’ kak region novogo tipa,” in Asimmetrii regional’nykh integratsyonnykh proektov XXI veka¸ Valerii Mikhailenko, ed. (Ekaterinburg: Ural University Press, 2018), 412–427; Lagutina, Russia’s Arctic Policy). Some of these assessments, although explicitly referring to the Arctic Zone, seem to be based on a wider definition of the Arctic. Kamenetskii, for example, claims that 100% of Russian diamond mining takes place in the Arctic Zone, although Russia’s most important diamond ore, Mir in the Republic of Sakha, is located far south of the current zone.

- 30 Matthieu Boulègue, Russia’s Military Posture in the Arctic: Managing Hard Power in a “Low Tension” Environment (London: Chatham House, 2019).

- 31 Laruelle, Russia’s Arctic Strategies.

- 32 “O Gosudarstvennoi komissii”

- 33 The archived version of the Rogozin Commission’s webpage is available at http://government.ru/department/308/about.

- 34 Inna Sidorkova and Natal’ya Galimova, “Rogozinu predlozhil vozglavit’ ‘Roskosmos’,” RBK, May 14, 2018. https://www.rbc.ru/politics/14/05/2018/5af5ab6a9a79477b78097533.

- 35 While the Arctic Zone stretches from the Norwegian border to the Bering Strait, the Far Eastern Federal Okrug covers eleven regions in Russia’s Pacific region (from the Arctic Ocean to the borders with China and North Korea).

- 36 Information about the Commission’s initial composition in March 2015 (governmental directive number 431-r) is available at http://government.ru/info/17320/, while its revamped December 2018 version (governmental directive number 2742-r) is available at http://government.ru/info/35054/.

- 37 See, e.g., Vladimir Putin, “Poslanie Prezidenta Federal’nomu Sobraniyu,” March 1, 2018. http://kremlin.ru/events/president/transcripts/messages/56957.

- 38 See, e.g., Helge Blakkisrud, “Governing the Governors: Legitimacy vs. Control in the Reform of the Russian Regional Executive,” East European Politics 31, no. 1 (2015): 104–121.

- 39 Curiously, in 2015 the plenipotentiary to the Volga Federal District, which has no territories in the Arctic Zone, was also included in the Commission.

- 40 In Figure 1, due to his position as Deputy Prime Minister, Trutnev is listed under “Government.”

- 41 Dmitrii Goncharuk, “K 80-letiyu Artura Chilingarova v Gosdume otkroetsya vystavka,” Parlamentskaya gazeta, September 25, 2019. https://www.pnp.ru/social/k-80-letiyu-artura-chilingarova-v-gosdume-otkroetsya-vystavka.html.

- 42 See, e.g., Ol’ga Kryshtanovskaya and Stephen White, “The Sovietization of Russian Politics,” Post-Soviet Affairs 25, no.4 (2009): 283–309.

- 43 However, commenting in the press on speculations about his potential inclusion in the State Commission prior to the actual appointment, Slipenchuk, a businessman-cum-scientist-cum-politician, emphasized that he had extensive experience from scientific work in the Arctic region as well as having organized expeditions to the North Pole (Ivan Safronov, Natal’ya Gorodetskaya and Sergei Goryashko, “Severnyi zakhvoz: Dmitrii Rogozin vozglavit komissiyu po upravleniyu Arktikoi,” Kommersant, February 6, 2015. https://www.kommersant.ru/doc/2661252.

- 44 For more on Epifanova, see A Just Russia’s website at http://www.spravedlivo.ru/597815.

- 45 “Artur Nikolaevitch Chilingarov.” Gosudarstvennaya Duma. http://duma.gov.ru/duma/persons/99100416/.

- 46 See, e.g., Atle Staalesen, “Russia Is Building a New Arctic. With Private Money,” The Barents Observer, April 19, 2019. https://thebarentsobserver.com/en/2019/04/russia-building-new-arctic-private-money.

- 47 “RZhD predlozhili perebrosit’ 80 mlrd rublei na Severnyi shirotnyi khod-2,” ZNAK, May 13, 2019. https://www.znak.com/2019-05-13/rzhd_predlozhili_perebrosit_80_mlrd_rubley_na_severnyy_shirotnyy_hod_2.

- 48 Alexander Sergunin and Valery Konyshev, “Forging Russia’s Arctic Strategy: Actors and Decision-Making,” The Polar Journal 9, no. 1 (2019): 75–93.

- 49 Kovtun has since been replaced as Governor of Murmansk, having asked to be relieved of her duties in March 2019, and is thus out.

- 50 Elizaveta Koroleva, “Razgrabili respubliku: eks-glava Komi vynesli prigovor,” Gazeta.ru, June 10, 2019. https://www.gazeta.ru/social/2019/06/10/12406441.shtml.

- 51 For the Kremlin’s practice of managing gubernatorial turnover via “voluntary” resignations, see Blakkisrud, “Governing the Governors.”

- 52 The president of the State Polar Academy was Artur Chilingarov, in Figure 1 listed under “presidential administration” as President Putin’s Special Representative to International Cooperation in the Arctic and Antarctica.

- 53 Here Chilingarov’s name pops up for the fourth time: while the Association of Polar Explorers was formally represented by Deputy President Aleksandr Orlov, Chilingarov is the organization’s president.

- 54 The final slot was filled by the Commission Secretary, which is a bit trickier to categorize. In Figure 1, the Secretary is in both cases listed as part of the governmental apparatus. In 2015, Rogozin’s assistant served in this function, in 2018 it was the Deputy Head of Trutnev’s secretariat.

- 55 “O Gosudarstvennoi komissii.”

- 56 For examples, see, e.g., Vitalii Petrov, “Interesy svoei Arktiki,” Rossiiskaya gazeta, February 28, 2016. https://rg.ru/2016/02/28/dmitrij-rogozin-rasskazal-senatoram-o-podderzhke-sevmorputi.html; Sergei Ptichkin, “Kak nam obustroit’ Arktiku,” Rossiiskaya gazeta, February 27, 2017. https://rg.ru/2017/02/27/dmitrij-rogozin-osvoenie-arktiki-vyhodit-na-novyj-uroven.html.

- 57 Material from the State Commission’s original webpage is archived on http://government.ru/department/308/about/. The Trutnev Commission’s webpage is located at http://government.ru/department/452/events/ and, from fall 2019, on https://arctic.gov.ru. We have conducted a simple word calculation of all texts published on these pages and then manually identified clusters of related words. As these websites appear to have been updated somewhat irregularly since 2017, we have complemented this material with a systematic reading of all articles referring to the work of the State Commission in the government’s official newspaper, Rossiiskaya gazeta, between January 2015 and September 2019.

- 58 Lagutina, Russia’s Arctic Policy, 59.

- 59 “Dmitrii Rogozin provel zasedanie Goskommissii po voprosam razvitiya Arktiki,” March 29, 2017. http://government.ru/news/27380/.

- 60 “Dmitrii Rogozin provel sovmestnoe zasedanie Goskomissii po voprosam razvitiya Arktiki i Morskoi kollegii pri Pravitel’stve,” December 8, 2015. http://government.ru/news/21070/.

- 61 This target had been put forward by Putin in his 2018 May Decrees, a list of targets to be achieved by the authorities by the end of his current presidential term (“Prezident podpisal Ukaz ‘O natsional’nykh tselyakh i strategicheskih zadachakh razvitiya Rossiiskoi Federatsii na period do 2024 goda’,” May 7, 2018. http://kremlin.ru/events/president/news/57425).

- 62 “Yurii Trutnev provel zasedanie prezidiuma Gosudarstvennoi kommissii po voprosam razvitya Arktiki,” April 10, 2019. http://government.ru/news/36350/.

- 63 See, e.g., “Dmitrii Rogozin provel zasedanie Gosudarstvennoi komissii po voprosam razvitiya Arktiki,” December 13, 2016. http://government.ru/news/25686/.

- 64 “Osnovy gosudarstvennoi politiki”, cf. Lagutina, Russia’s Arctic Policy, 32.

- 65 Mia Bennett, “Russia and China Claim Success at Yamal LNG,” The Maritime Executive, December 15, 2017. https://www.maritime-executive.com/editorials/russia-and-china-claim-success-at-yamal-lng.

- 66 “Dmitrii Rogozin provel zasedanie prezidiuma Goskomissii po voprosam razvitiya Arktiki,” March 9, 2016. http://government.ru/news/22162/; “O resheniyakh po itogam zasedaniya prezidiuma Goskomissii po voprosam razvitiya Arktiki,” March 10, 2016. http://government.ru/orders/selection/401/22291/; see also Igor’ Zubkov, “A my poidem na sever: gosprogrammu po razvitiyu Arktiki otsenili v 214 milliardov rublei,” Rossiiskaya gazeta, January 23, 2017. https://rg.ru/2017/01/23/gosprogrammu-po-razvitiiu-arktiki-ocenili-v-214-milliardov-rublej.html; Dmitrii Orlov, “Razvitie Arkticheskoi zony Rossii i osnovnye vyzovy dlya ego osvoeniya,” Regnum, April 25, 2018. https://regnum.ru/news/2407690.html.

- 67 Lagutina, Russia’s Arctic Policy, 83–86.

- 68 Aleksei Mikhailov, “Khab vsemu golova,” Rossiiskaya gazeta, August 29, 2017. https://rg.ru/2017/08/29/reg-szfo/mintrans-sokratil-rashody-na-murmanskij-transportnyj-uzel.html; RSMD, “Vo skol’ko Arktika obkhoditsya Rossii?” March 12, 2018. https://russiancouncil.ru/analytics-and-comments/interview/vo-skolko-arktika-obkhoditsya-rossii/. In addition, the development has been hit by Western sanctions that target investment in certain sectors, e.g., exploitation of offshore hydrocarbon resources.

- 69 This has not been reflected in a corresponding willingness to give private businesses access the Commission.

- 70 “Yurii Trutnev provel.”

- 71 Ibid.

- 72 Quoted by Ptichkin, “Kak nam obustroit’.”

- 73 “Dmitrii Rogozin provel zasedanie Goskommissi.”

- 74 “Yurii Trutnev provel.”

- 75 Vladimir Putin, “Plenarnoe zasedanie Mezhdunarodnogo arkticheskogo foruma,” April 9, 2019. http://kremlin.ru/events/president/news/60250.

- 76 According to the decree defining the State Commission’s mandate, it is to “ensure a favorable operational regime in the Arctic Zone of the Russian Federation, including the creation and maintenance of the necessary combat potential of the regular troops of the armed forces of the Russian Federation, other troops, military units and bodies (primarily border agencies) in this region” (“O Gosudarstvennoi komissii”).

- 77 One explanation may also be that Arctic development decisions are taken elsewhere. Observers have pointed to the Security Council as a key forum for forging consensus and disseminating plans and policies (Sergunin and Konyshev, “Forging Russia’s Arctic Strategy”).

- 78 See, e.g., “Dmitrii Rogozin provel zasedanie Gosudarstvennoi.”

- 79 Vladimir Putin, “Zasedanie Soveta Bezopasnosti po voprosu realizatsii gosudarstvennoi politike v Arktike,” April 22, 2014. http://kremlin.ru/events/president/news/20845.

- 80 Daniel Treisman, After the Deluge: Regional Crises and Political Consolidation in Russia (Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 1999).

- 81 Blakkisrud, “Governing the Governors.”

- 82 Gulnaz Sharafutdinova and Rostislav Turovsky, “The Politics of Federal Transfers in Putin’s Russia: Regional Competition, Lobbying, and Federal Priorities,” Post-Soviet Affairs 33, no. 2 (2017): 161–175.

- 83 Lagutina, Russia’s Arctic Policy; Mariya Nazukina, “Osnovnye trendy pozitsionirovaniya regionov Rossiiskoi Arktiki,” Labirint no. 5: 59–68.

- 84 See Mikhailov, “Khab vsemu golova.”

- 85 Dmitrii Orlov, “Razvitie Arkticheskoi.”

- 86 Natalia Zubarvich, “The Fall of Russia’s Regional Governors,” Carnegie Moscow Center. October 12, 2017. https://carnegie.ru/commentary/73369.

- 87 “O Gosudarstvennoi komissii”

- 88 The sole exception is the director of the Murmansk Marine Biology Institute (included in the 2015 Commission).

- 89 The 80 million ton-target had initially been introduced in 2015 in connection with the adoption of a state project for the development of the NSR, but then with a 15-year timeframe: by 2030 (Vladimir Kuz’min, “Medvedev utverdil proekt razvitiya Severnoi morskoi puti,” Rossiiskaya gazeta, June 8, 2015. https://rg.ru/2015/06/08/medvedev-site.html).

- 90 Anastasiya Vedeneeva, Dmitrii Kozlov and Denis Skorobogat’ko, “Trillion zalozhat za polyarnyi krug,” Kommersant, January 21, 2019. https://www.kommersant.ru/doc/3859550.

- 91 “Osnovy gosudarstvennoi politiki.”

- 92 Lagutina, Russia’s Arctic Policy, 83.

- 93 The advanced special economic zones were originally introduced in 2014 to stimulate economic growth in the Russian Far East, but since 2018, it has been possible to establish them across the Russian Federation (Jiyoung Min and Boogyun Kang, “Promoting new growth: ‘Advanced Special Economic Zones’ in the Russian Far East,” in Russia’s Turn to the East: Domestic Policymaking and Regional Cooperation, Helge Blakkisrud and Elana Wilson Rowe, eds. (Palgrave Macmillan, 2019), 51–74).

- 94 Quoted in Andrei Petrov, “Osvoenie Arktiki 2.0: opornye zony kak severnye forposty Rossii,” Ekonomika segodnya, March 11, 2016. https://rueconomics.ru/164259-osvoenie-arktiki-20-opornye-zony-kak-severnye-forposty-rossii.

- 95 See, e.g., Ledeneva, Can Russia Modernise?

- 96 “Dmitrii Rogozin provel sovmestnoe.”

- 97 Pravitel’stvo, “Dmitrii Rogozin provel zasedanie Gosudarstvennoi.”

- 98 Although Rogozin remained Chair of the State Commission until May 2018, the webpages were not updated with new texts for the final 14 months of his tenure. The last session reported on the official website was the one held in conjunction with the March 2017 Arctic Forum. This does not mean that there was no activity, however. For example, Rossiiskaya gazeta covered a June 2017 session of the State Commission in Sabetta (Elena Matsiong, “Dmitrii Rogozin provel vyezdnoe zasendanie Goskomissii v portu Sabetta,” Rossiiskaya gazeta, June 15, 2017. https://rg.ru/2017/06/15/reg-urfo/rogozin-provel-zasedanie-v-portu-sabetta.html), but for some reason this was not reported on the Commission’s own website.

- 99 Quoted in Regnum, “Medvedev izmenil sostav kommissii po razvitiyu Arktiki,” December 11, 2018. https://regnum.ru/news/2535748.html.

- 100 Quoted in Krasnaya vesna, “Sovet bezopasnosti RF: neobkhodimo sozdat’ gosorgan dlya razvitiya Arktiki,” December 6, 2018. https://rossaprimavera.ru/news/70ae03bf.

- 101 Kira Latukhina, “Arktika – delo tonkoe,” Rossiiskaya gazeta, January 18, 2019. https://rg.ru/2019/01/18/reg-dfo/putin-podderzhal-ideiu-medvedeva-pereimenovat-minvostokrazvitiia.html.

- 102 It was also decided that the institutions established for channeling investment and development in the Far East, such as the Far East Development Corporation and the Far East Investment and Export Agency, now would extend their activity to the Arctic.

- 103 Aleksei Mikhailov, “Arktika kak investproekt,” Rossiiskaya gazeta, June 18, 2019. https://rg.ru/2019/06/18/reg-szfo/na-kakie-preferencii-smogut-rasschityvat-biznesmeny-v-arktike.html.

- 104 See, e.g., Rogozin’s complaints quoted in Ptichkin, “Kak nam obustroit’.”

- 105 Mikhail Belikov, “Poslednyaya versiya?” Rossiiskaya gazeta, October 9, 2019. https://rg.ru/2018/10/09/reg-szfo/zakon-o-razvitii-arkticheskoj-zony-rassmotriat-v-ocherednoj-raz.html.

- 106 Gel’man, “The Vicious Circle;” Gel’man and Starodubtsev, “Opportunities and Constraints.”

- 107 See, e.g., Vladimir Leksin and Boris Porfir’ev, “Peresvoenie rossiiskoi Arktiki kak predmet sistemnogo issledovaniya gosudarstvenno-tselevogo upravleniya: voprosy metodologii,” Ekonomika regiona no. 4 (2015): 9–20.

- 108 Laruelle, Russia’s Arctic Strategies, 5–6.

- 109 Treisman, The New Autocracy.

- 110 Monaghan, Defibrillating the Vertikal?