Introduction

In 2012, an indigenous organization called Izvatas, representing the Izhma-Komi ethnic group from the northwest Russian Arctic, organized an international conference ”Arctic Oil: Exploring the Impacts on Indigenous Communities,” under the auspices of Greenpeace International. It took place in Usinsk, the Komi Republic. The delegates issued a draft resolution, the Joint Statements of Indigenous Solidarity for Arctic Protection, signed by 15 indigenous groups, including two permanent participants in the Arctic Council (AC).1 In 2013, during the AC ministerial meeting in Kiruna, Sweden, the statement was presented and promoted for the public as the united position of the Arctic indigenous peoples. However, further expansion of the coalition was blocked by the Inuit Circumpolar Council (ICC), which has strongly criticized Greenpeace for its ‘attempt to speak on behalf of the Arctic communities.’2

In 2015, Nikolay Rochev, the chairman of Izvatas, visited Nunavut, Canada during the next AC ministerial meeting. Rochev told the Inuits about the Izhma-Komi’s experience of living next to oil extractive activities and called on the ICC to join the coalition demanding action from the AC to protect the rights of indigenous peoples impacted by oil and gas development in the Arctic.3 Given the expressed concerns of the ICC that the coalition was backed by Greenpeace, Rochev reacted in the following way: “There is a common assumption that environmentalists and corporations use indigenous peoples for their interests. Why shouldn’t we assume that it can be the other way around?.”4 Soon after the trip to Nunavut, Izvatas and Lukoil-Komi, a Russian oil and gas development company, signed an official agreement. The agreement granted Izvatas’ constituents a right comparable to Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC) and thus created a precedent. For the first time in contemporary history, Lukoil signed an agreement directly with an indigenous organization (IO) representing a group whose recognition as ‘indigenous’ is withheld by the Russian authorities.5

These events highlight numerous interrelated issues that current debates widely frame and discuss in the language of governance and politics of recognition. The contemporary Arctic region is becoming a competitive arena for diverse nonstate actors (both insiders and outsiders), including indigenous organizations, corporations, environmental and conservation groups. In a globally networked society, these actors are increasingly linked to each other by a large number of formal and informal connections, ‘through horizontal patterns of communication and exchange.’6 Horizontal (reciprocal) relations between these networks provide nonstate actors with an effective tool to gain recognition from the Arctic nation states and politicians. To be accepted as a useful contributor in governance debates, especially in areas of high stakes, these nonstates are becoming engaged in dynamic, network-based processes of coalition building, and increasingly using the opportunities offered by globalization and communication revolution.

There is another side to these events related to a widely shared observation in sociological and international relations debates concerning the ambiguous nature of indigenous rights.7 While different actors may agree on the general purpose of the norms, respect and protection of the rights of indigenous peoples, they may contest the specific parameters of these norms. Who is indigenous, and who is not? Who can speak on behalf of indigenous peoples and who cannot? In which situations should these norms be applied? All of these questions are relevant to the Russian extractive context. As Russia’s approach to the recognition of indigenous peoples differs from those applied by international organizations, the extractive context seriously jeopardizes the situation of peoples whom the authorities do not consider “indigenous,” which makes their rights even more vulnerable to violations. Over the last decade, a growing scholarship on indigenous issues has generated considerable knowledge on indigenous agency (power) in an extractive context across the Russian Arctic.8 However, when it comes to studying how indigenous actors assert their agency in horizontal, less hierarchical relations with other nonstate actors, there certainly is a need for more comprehensive analysis.

This article addresses the issue of agency and its influence when it comes to contesting indigenous rights norms in an extractive context from the perspective of organizations representing people whose recognition as ‘indigenous’ is withheld by the Russian authorities. The term ‘indigenous organizations’ (IOs) is used here in a broader sense to include different types of entities, created by indigenous peoples to protect their rights and to serve the diverse interests of their communities (societal, economic, political, etc.). Rather than viewing these entities in isolation and as a mere part of Russian civil, business and political society, the article places them in global communication networks and observes their direct involvement in the governance of extractive activities, albeit mainly at the local level. The article analyzes the horizontal relationships between these IOs and other indigenous and environmental organizations and oil companies to explore the scope of their agency (power) and better understand the resources and strategies that help them to succeed in a given context. The core issues the article presents are: whether and how these IOs can succeed in their attempts to contest the norms, which they perceive as unjust and illegitimate, under a political regime that is flawed in terms of rule of law, good governance, and human rights commitments.

The analysis is designed as an in-depth case study, and traces the activities of the Izhma-Komi IOs in a local extractive context. The analysis considers the experience of changing norms by Izhma-Komi IOs as an outstanding case, rather than as a representative trend in the Russian North. Two notable observations argue for the uniqueness of the case. Despite the lack of recognized indigenous status, these IOs managed to reach a stakeholder agreement with Lukoil that granted their constituents rights comparable to FPIC. In contrast to many companies involved in onshore resource extraction in the Russian Arctic, Lukoil is receptive to the issue of indigenous rights as well as corporate social responsibility (CSR).9

The choice of Izhma-Komi IOs, however, needs additional explanation since there are numerous research articles that have been published on the Izhma-Komi.10 Existing studies address issues of governance and recognition with a focus on the Izhma-Komi’s hierarchical relationship with the Russian state, and explore the reasons why the Izhma-Komi have failed to ‘be recognized by the authorities as indigenous.’11 Unlike these authors, yet inspired by their findings, I have focused on an analysis of Izhma-Komi IOs’ horizontal relations with other indigenous and environmental organizations and with Lukoil company, taking a different methodological approach to concepts of governance and recognition. The article contributes to the debate in a twofold way. Firstly, the study argues that, even though the agency of Russian IOs in governing extractive activities remains negligible, the prevailing ‘victim’ paradigm falls short in portraying the contemporary situation, which has emerged in a domain beyond the IOs hierarchical relationship with the state. Secondly, the study argues that focusing on the governance perspective and approach to recognition from ‘below’ provides a useful lens to explore a broader spectrum of the relations these organizations engage in, as well as their strategies to contest norms in the authoritarian normative context of Russia.

The article consists of six sections. Following the introduction, the second part presents an approach to studying interrelations between norms, agency, and recognition in an extractive framework of governance. The third part describes the case study and methodology. The fourth part reviews legal norms, which constitute indigenous rights and recognition in the Russian extractive context today to show what norms the Izhma-Komi organizations have tried to recategorize vis-à-vis their interactions with indigenous, environmental, and corporate actors within the local domain of extractive governance. The fifth part explores three agential strategies of the Izhma-Komi organizations to show how using specific resources and outcomes has enabled a normative shift in their relations with environmental organizations and with the oil company. The final part presents the conclusion and discussion in light of current debate and implications for future studies.

2. Norms and agency in the governance framework: interrelations through actors’ mutual recognition

Unlike state-centered approaches to studying issues of governance and recognition, this analysis draws on other families of approaches: governing as governance, and recognition from ‘below.’ Both approaches, while acknowledging the dominance of the state institutions in governance and recognition processes, aim to bring into view non-state actors and a much broader spectrum of their relations, occurring outside the state level. These approaches provide a useful lens for explaining the influence of agency and power of indigenous actors and the importance of local context in contesting norms.

The etymological denotation of the term governance comes from the Latin word gubernare, which means ‘to direct, rule, govern.’ Despite the contested connotations of the concept, it is often used as a ‘means of encapsulating the collective steering of society in the provision of collective goods.’12 Governance in its broad sense suggests that in governing modern societies, not only the state but two other societal entities, markets and civil society, have a prominent role.13 Governance inherently refers to the process of organizing societal entities within a ‘state-market-society’ triangular framework with multidimensional and multileveled interactions directed to respond to major societal problems and to create societal opportunities.14 Each of the vertices of the triangle is viewed as a group of diverse organizations, peoples, practices, and networks, rather than as a single actor. Their relations are examined as socially constructed, normative, and contextually based; moreover, they imply power dynamics and have processual and outcome dimensions.

Norms, as one of the key institutional elements of governance and recognition, entail a dual quality.15 The dual quality of norms implies that norms are both stable (structuring) and socially constructed, and, thus, interrelated with the agency (flexible). The notion of ‘agency’ is considered as the ‘capability of the actors in doing things to act independently of social structures in making their own decisions, choices and to act upon them,’ which inherently ‘implies the exercise of power.’16 Norms, as social constructs, never remain valid by themselves but need constant affirmation by the actors through their agency and interactions in a particular context. Owing to the dual quality of norms, actors have agency either to reproduce dominant norms within the structures or to utilize the possibility of at least slightly ‘contesting’ and ‘reconfiguring’ the meaning of these norms. Agency, whether individual or collective, can take many forms, which vary from resistance to ‘not acting,’ depending on the amount and character of resources available to the actors to exercise it.17 The resources, ‘allocative’ (material) and ‘authoritative’ (non-material), can vary significantly in different institutional arenas and domestic contexts.

A recognition approach ‘from below’ is useful to explain IOs’ practices of norms contestation within a governance triangle. The approach originates from a broader, ontological perspective of understanding recognition as an irreducible dimension of any practice of calling into question the dominant power relations and prevailing social norms of society from the position of those without institutional power.18 From this perspective, indigenous claims for recognition are not limited to claims made on the state for state recognition; they can be equally concerned with material and symbolic, structural, and subjective issues.19

In a nutshell, this approach to contesting norms by indigenous actors centers on an understanding of the ambiguous character of indigenous rights norms. That is, their content, proscriptions (what the norm enables and prohibits) and parameters (the situation in which the norm applies) may be a subject to different interpretations. It argues that in any relation, actors mutually recognize themselves and each other in numerous ways, often simultaneously. In terms of appropriate behavior in these relations, actors rely on their background information and the local context. Because actors may not share a common context or background, this can generate disagreement over norm components and lead to contesting the norm. Indigenous actors, as holders of a counterpower, present their contestation claims to dominant actors, both state and non-state, with an aim to engender social transformation and to contribute to broader norms, principles, and institutions.

Studies describe contemporary Russian governance as an irregular triangle, where the tripartite relationship between ‘state-business-society’ is practically nonexistent.20 However, bilateral relations do exist between the vertices of the triangle: government with business, government with society, and society with business.21 In all these relationships, the government plays the most assertive role, setting up the terms of the dialogue vis-à-vis society and business, and controlling who can participate. Russian civil society and IO entities are subject to paternalistic attitudes by the state and given a passive role. In the ‘Russian style’ of CSR the state does not merely function as an intermediary; in fact, the state deliberately replaces IOs in their relations with the business sector, dictating what the IOs need, and forcibly imposing a sort of ‘social tax’ on business.22

While this governance system serves badly all the parties involved, promoting corruption, feeding paternalistic expectations, and circumscribing them from learning by dialogue, the IOs end up paying the highest price from both a short- and long-term perspective. Among the significant structural shortcomings for the IOs in this governance system is a lack of institutionalized forums for dialogue with the authorities and business at the initiative of the IOs (except in extreme events, such as protests). Though Russian IOs benefit from new resources that globalization, the digital revolution, and internalization of the indigenous movement have made possible, the Russian authoritarian regime tends to control and limit the availability of these resources to indigenous actors. An alliance with global indigenous and environmental opposition, once the most powerful and effective tool to pressure authorities and business towards indigenous rights commitment, is no longer a safe option, owing to recent restrictions on NGOs policy and regulatory obstacles (‘foreign agent law,’ ‘undesirable organizations law’).23 Due to the backlash against IOs as ‘foreign agents’, several IOs were blacklisted for receiving external funding, while others terminated joint projects with international partners.24

3. Presenting a case and a methodology

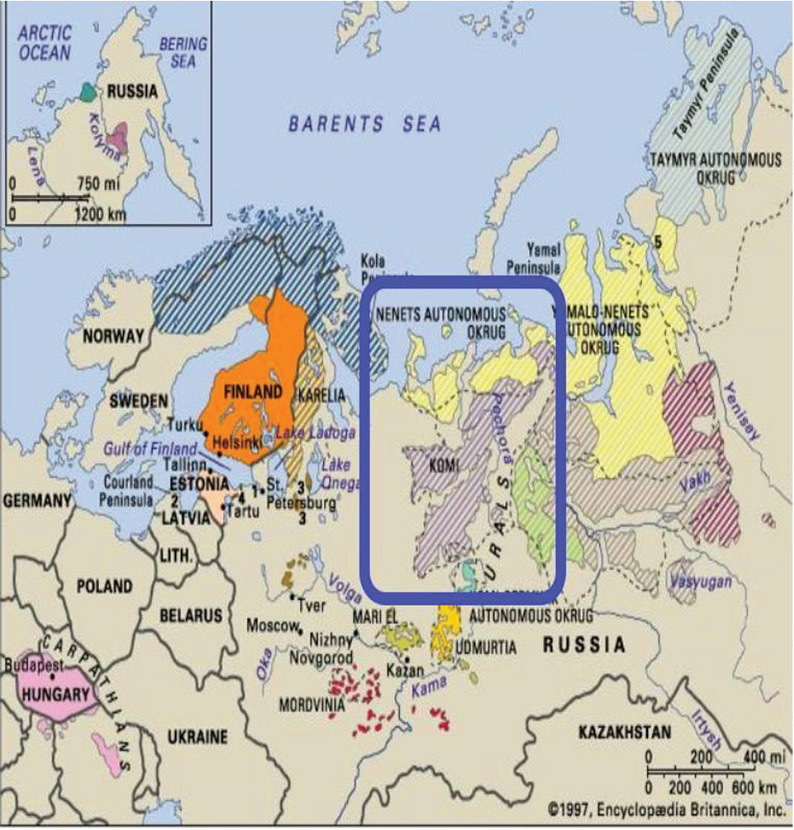

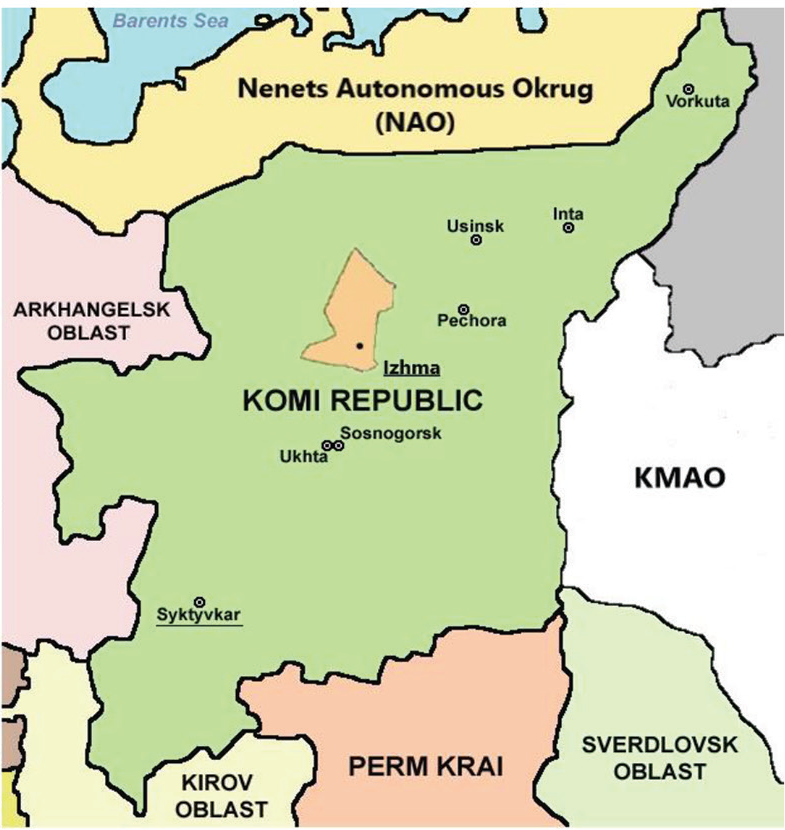

Izhma-Komi or Izvatas is one of the most distinctive subgroups within the Komi people, the titular minority of the Komi Republic in the northwest Russian Arctic (Figure 1). Although nowadays the group is settled across the territories of the eight regions of Russia, its largest community resides in Izhma municipality of the Komi Republic.25 The Izhma-Komi is the only subgroup of the Komi engaged in reindeer husbandry. It has its own language (a dialect of Komi), a strong local identity, and a high degree of group solidarity.26 Like their predecessors, the Izhma herders continue to practice large-scale reindeer husbandry aimed at industrial livestock production of meat, skin, and velvet antlers. Their lifestyle is semi-nomadic. Although the reindeer graze on the Bolshezemel’skaya Tundra, the herders have their large permanent settlements at Izhma municipality in Sizyabsk, where their families live and where they return with their herds each winter.27 As part of the tundra between the White Sea and the Urals, Bolshezemel’skaya Tundra covers the contemporary territories of two subjects of the Russian Federation: the Republic of Komi and the Nenets Autonomous Okrug (NAO). The geographical proximity to NAO along with their semi-nomadic reindeer husbandry makes the Izhma-Komi ‘to the largest extent connected with the Nenets population of the tundra,’ in terms of history, culture, language, trade and close kinship, through intermarriages.28

In the story of the Izhma-Komi and their relationship with the state, history matters significantly. The Komi Republic is one of Russia’s peripheral regions, whose territorial borders, status in the official administrative hierarchy, and population composition changed dramatically because of Soviet economic and nationalities policies. The Republic received its national-territorial autonomy in 1921, while it lost access to the Arctic Ocean and a large part of the Bolshezemel’skaya tundra, which was assigned to the newly established Nenets Okrug, following administrative-territorial reforms in 1929.29

In the Soviet system of governance, the autonomous status of the national territory reflected its place in the administrative hierarchy (in declining order from union republic to autonomous republic, to autonomous oblast, to national autonomous okrug) and assumptions about its titular nationality for self-governance.31 Given the ideologically declared ‘backwardness of small nationalities of the North,’ Soviet legislators granted them ‘titular nationality’ in okrugs, but never in oblasts or republics. Because of the Republican status of the Komi autonomy, the central authorities denied Izhma herders’ demand for recognition as a ‘small nationality of the North.’ As a result, the authorities expelled Izhma-Komi from ministerial official statistics and directives on ‘small nationalities of the North’ and, thus, excluded them from special state protection and support.32

Despite using the Izhma’s herding style as a ‘blueprint’ for the development of reindeer husbandry in the remote territories of the Soviet North, the central authorities never considered reindeer husbandry among the priorities for the Komi regional economy.33 In the command economy, the Komi’s economic objectives were extensive industrial exploitation of the Republic’s vast natural resources. The Komi’s modern history of industrial development originates in the late 1920s, when processes of nation-state building in the Soviet Union were especially active and when the northern periphery of the vast territory became an important land frontier for forced industrialization and expansion of the GULAG system until the end of 1950s. The industrial development of the Timan – Pechora oil and gas province, the Pechora coal basin, construction of the North Pechora Railway, internal migration, and the forced displacement of peoples from other parts of the U.S.S.R, have largely influenced demographic processes in the Republic and the composition of its modern population. One result was a huge long-term decline of the Komi within the Republic’s population: from 92% in 1926 to 24% in 2010.34 As the Komi became a minority within their national Republic, the Izhma-Komi became a minority within the minority, bearing the costs of the expansion of the country’s resource-based economy.35

The case study applies sociological and historical analysis to examine the activities of two Izhma-Komi organizations, Izhemskiy olenevod i Ko and Izvatas, within the timeframe 2000–2018. The empirical data was collected using qualitative methods, including in-depth semi-structured interviews, analysis of documents, and participatory observation during three study trips to the Komi Republic in February and June 2012, and in March 2018. All interviews were conducted in Russian, and the majority were recorded. The final list of informants comprises 29 individuals selected through a purposive sampling technique. These informants included managers, staff, and activists from Izhemskiy olenevod i Ko, Izvatas, Save the Pechora Committee, and Fraternity of Izvatas, as well as representatives from the Izhma municipal authorities, regional academics, and journalists. In addition to the Komibased informants, indigenous experts and activists in Moscow (November 2018), St. Petersburg (May 2018), and Tromsø (October 2018) were also interviewed. Documents analyzed were archival materials of Izvatas (1989–2014), Izhma municipality (2003–2017), open-access reports on CSR of Lukoil-Komi (2003–2017), and publications in the media covering Izhma-Komi, Izvatas, Izhemskiy olenevod i Ko, and Lukoil-Komi. The participatory observation was conducted during the Izhma-Komi festival Lud and the Sixth Congress of Izvatas, both in June 2012. The data collected were transcribed and analyzed by a mix of techniques, including coding and interpretative analysis. The analysis of primary data was combined with secondary data analysis, collected through desk-research. Triangulation of data sources and data collection methods was applied to increase the credibility and validity of the results.

4. Izhma-Komi status at the Russian indigenous governance and recognition order

As Jakeet Singh states, norms of indigenous legislation serve the governors (government) to contour ‘indigenous-non-indigenous’ boundaries and to charge indigenous policy: by (de)legitimizing those of the claimants, who will be targeted or excluded by the policy and who will be granted or denied the rights and benefits related to the indigenous status.36 The analysis distinguishes between two groups of norms within Russian indigenous governance and recognition, in order to assess the current legal status of the Izhma-Komi people in an extractive context: norms on the recognition of indigenous status, and norms on the recognition of special indigenous rights within the extractive context.

As Russia is a multi-ethnic country (the 2010 national census lists 194 ethnic groups), its recognition approach differs from those applied by the UN system bodies, the International Labor Organization (ILO), and the World Bank. The country has refrained from endorsing the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, and has not ratified ILO Convention 169. The Russian state approach to ‘who is indigenous’ is established by the category of korennye malochislennye narody (KMN). The law defines KMN as ‘peoples living in the territories of the traditional settlement of their ancestors, preserving a traditional way of life and a traditional economic system and activities, numbering within the Russian Federation fewer than 50,000 persons, and recognizing themselves as independent ethnic communities.’37 The numerical hallmark divides the country’s indigenous population into two groups: KMN or small-numbered (less than 50,000) and large-numbered (more than 50,000). As the majority of KMN live in the northern territories of Russia, the legislator specifically introduced a category of korennyye narody Severa, Sibiri i Dal’nego Vostoka (KMNS). As legitimate claimants to special rights and protection in extractive contexts, the authorities only consider groups meeting all the criteria of the state’s definition of ‘indigeneity,’ i.e. KMN and KMNS. Consequently, the present number of those who can claim KMNS status in Russia and its related rights has been limited by the authorities to only 40 groups.38 Given the fact that, since 2000, the state has not recognized a single ethnic group as KMNS, some scholars have even introduced the idea of so-called ‘recognition moratorium’ in the country.39

Article 69 of the Constitution of the Russian Federation (1993) guarantees KMN rights according to universally recognized principles and norms of international law and international treaties signed by Russia. In the early 2000s, Russian authorities identified the fundamental rights of indigenous peoples and normatively affirmed them in three federal laws: ‘On the Guarantees of the Rights’ (1999), ‘On Organization of Obshchinas’ (2000), and ‘On Territories of Traditional Nature Use’ (2001).40 These constitutionally protected rights include, but are not limited to, the following: right for judicial protection of lifestyles, cultures, and languages; right to participate in self-government; right to establish and co-manage the Territories of Traditional Nature Use (TTNU);41 guarantees on using land in TTNU free of charge for traditional economic activities; right to compensation for damages due to extractive and developmental activities in their TTNU; right to form Obshchina;42 and right to alternative military service. During Putin’s presidency, legal norms relating to indigenous peoples have become subject to ongoing changes, leading to an erosion of indigenous peoples’ rights regarding land, natural resources use, and political and public participation.43

The second group of norms, according to the analysis, refers to recognition of the special rights of indigenous peoples within an extractive context. Globally, norms of protection of indigenous rights are united and promoted under the umbrella of the FPIC principle.44 In the mid-1980s, states and corporations worldwide began to affirm the normative foundations of the FPIC by committing themselves to align their extractive operations in consultation with affected indigenous communities, recognizing their right to contribute to decision-making processes. In Russian legislation, legal norms relating to indigenous people in an extractive context constitute derivatives from the norms assigned to the KMN and KMNS, because the authorities only grant special rights and protective guarantees in a developmental context to groups with KMN and KMNS status. This group of norms is subject to a tangled web of federal, regional, and local regulations, which in aggregate are unstable, contradictory, often simulative, undeveloped, and lack full compliance with the international legal requirements of FPIC.45 While Russian legislation formally requires informing, consulting, and allowing participation of KMN (largely through public hearings), the lack of consistent incorporation of the FPIC and enforcement mechanisms in the country’s federal legislative framework is a serious threat to the fundamental rights of indigenous peoples.46

In the legal reality of the federal Russian state, these norms both de jure and de facto, as well as the gap between them, vary significantly from one region to another. Given the asymmetrical character of federal indigenous governance, eight regions of the Arctic Zone of the Russian Federation (AZRF) can be broken down into two groups in terms of protection of indigenous peoples in an extractive context.47 The first group is comprised of only three regions: Nenets Autonomous Okrug, Yamal-Nenets Autonomous Okrug, and the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia). These regions have relatively progressive regional legislation and law enforcement mechanisms (such as an ombudsman for indigenous rights, ethnological expertise, damage and compensation assessment due to industrial development) to protect indigenous rights guaranteed under their jurisdiction.48

The Komi Republic falls into the second group, comprising the rest of the AZRF regions, characterized by a poorly developed agenda on issues related to indigenous peoples and which does not receive priority attention from the regional governors. Despite Izhma-Komi applications for KMNS status, the authorities continue to consider them non-KMNS. Instead, they are listed as the Komi ethnic group, with a population of 202,348 people, according to the 2010 census. The Izhma-Komi’s rights concerning extractive industries lack a special legal designation and are left to be regulated by the universalistic norms of the Russian Constitution, sectoral laws (Water-, Forest-, Land Codex, and Fishing Law), and less formal agreements between their organizations and extractive corporations.

5. Izhma-Komi organizational strategies to contest existing norms

5.1 Mobilizing legitimacy through ‘inter-indigenous’ recognition

The authorities have always recognized reindeer husbandry as one of the traditional activities of the indigenous peoples of the North, and the Izhma-Komi as reindeer herders.49 Both Izhma-Komi organizations have attempted to use ‘reindeer herding’ markers to claim their legitimacy as indigenous, albeit toward different recipients and using different administrative and communicative channels.

The cooperative of reindeer herders Izhemskiy olenevod i Ko (1992) was based on a bankrupt state farm (sovkhoz) Izhemskyi in Sizyabsk. In 1994, the cooperative was one of the largest in the European Russian North totaling 31,000 reindeer and 345 herders, organized in 21 brigades.50 The herders were primarily from the Izhma-Komi ethnic group, with a few herders from a mixed Izhma-Komi and Nenets ethnic origin, often belonging to related families. After the collapse of the Soviet command economy and a radical decrease in northern welfare benefits and subsidies, the Izhma herders, like other northerners, strived to survive in the new free-market reality. In the early 2000s, the economic situation in the country stabilized, and the authorities began to support reindeer husbandry again. However, in contrast to herders in neighboring NAO, this change was not positive for the Komi herders.

Historically, NAO was founded and designed as the first ethnically defined territory for small nationalities of the North. The European Nenets served as a model of integration into socialist society in line with Soviet nationalities and economics policy.51 The Russian authorities have continued to promote and intensively subsidize reindeer husbandry in NAO, considering it one of the central elements of the region’s social and economic profile.52 NAOs was the fourth region to issue a special law ‘On reindeer husbandry’ (2002),53 as the Nenets reindeer cooperatives turned into the ‘North’s pioneers’ in signing private agreements with oil and gas companies designed to negotiate terms of co-existence.54

After the federal reindeer husbandry subsidies came into force, Izhemskiy olenevod i Ko moved from the Komi region to neighboring NAO, re-registering their property in 2005. At the time, NAO was experiencing a dramatic decline in reindeer, and the authorities had strong political and economic interest in receiving 32,000 healthy Izhma reindeer into regional Agriportfolio. Favorable subsidies on reindeer meat production and helicopter transportation to the tundra were part of the bargain between the Izhma-Komi herders and the NAO authorities, promoting a ‘win-win’ solution.55

But even after the cooperative registered in NAO, the herders kept their houses and families in Izhma municipality. The cooperative also had an office and a small suede production factory in Sizyabsk, employing some of the herders’ wives and relatives. Working in NAO on a rotational schedule, the herders returned from the tundra with their herds to their families in Komi. Every summer the herders’ children left Komi for NAO to help their fathers during the school vacation. In 2018, all 260 herders of the cooperative were from Komi.

The other Izhma-Komi organization, Association Izvatas, was founded in Izhma in 1990 on a wave of indigenous mobilization and activism, due to Glastnost and in response to growing ecological devastation and industrial expansion in the North.56 During the 1990s, despite the active engagement of the first leaders of Izvatas in the post-Soviet indigenous movement, Izvatas did not enjoy official membership in the Russian Association of Indigenous Peoples of the North, Siberia and Far East (RAIPON). RAIPON, acting on behalf of all Russian indigenous peoples, holds status as the most politically resourceful and networked indigenous organization in Russia, recognized both by the Russian government and the international community.57 The leadership of Izvatas has looked into asserting its legitimacy through inter-indigenous recognition by obtaining membership in RAIPON.

Izvatas membership in RAIPON remained an issue until the V RAIPON Congress in October 2004.58 According to the informants, Congress delegates were divided into two camps regarding Izvatas’ application for membership. Opponents expressed their concerns about further expansion in membership in the organization, and argued that membership in RAIPON must correspond with the National List of KMNS (2006). Proponents insisted that the question of ‘inter-indigenous’ recognition should determine membership in RAIPON. They further claimed that the indigenous community should act differently from the Russian state and above all according to norms of indigenous solidarity, reciprocity, and commitment to the international right of indigenous peoples for self-determination. The results of the Russian Federation 2002 Census, with an estimated 15,608 persons identifying as Izhma-Komi, were considered an additional favorable factor for officially granting Izvatas RAIPON membership in 2004.59

By using ‘inter-indigenous’ recognition, both Izhma-Komi organizations have promoted their organizational legitimacy and strength. They have successfully capitalized on capacity building, networking, and aligning with indigenous partners domestically and internationally (e.g., International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs, Association of World Reindeer Herders, Institute for Ecology and Action Anthropology). Membership of Izhma-Komi organizations in RAIPON and the Reindeer Herders’ Union of Russia has granted Izhma-Komi school graduates with fellowships to continue their studies at the Institute of Peoples of the North under the federal education program for indigenous youth. More importantly, in the context of growing oil extractive developments in NAO and Komi, piggybacking with KMNS (organizationally and symbolically) has provided Izhma-Komi organizations with a crucial authoritative resource in their negotiations with the Lukoil company, as will be elaborated upon below.

Herding and registration in NAO allowed Izhemskiy olenevod i Ko to claim its legitimacy as a stakeholder and to start signing private agreements with oil and gas companies operating in NAO’s Bolshezemelskaya tundra since 2005. However, Izvatas, speaking on behalf of the whole Izhma-Komi community, including those not involved in reindeer herding, lacked similar resources. Izvatas urgently needed to explore and mobilize additional resources to negotiate the rights of their constituents in an oil extractive context, if not as KMNS, then at least as a rights-bearing community.

5.2 Strengthening through alliances with environmentalists

In an extractive context, the rights of large indigenous groups (more than 50,000), which include Izhma-Komi, are subject to the universal norms in the Constitution, other federal legislation as well as less formal agreements with extractive corporations. Studies have widely debated the agreements made between corporations and indigenous groups in terms of CSR, whereby corporations have voluntarily integrated the social and environmental concerns of their stakeholders into their business operation.60 Those Russian oil corporations that are part of the global supply-chain of hydrocarbon resources must not only comply with domestic legislation, but also with international CSR guidelines, which unanimously recognize local communities affected by the company’s operations as key stakeholders and as a ‘rights bearing’ community.61

CSR in Russia, as described in the theoretical chapter, is determined by the country’s irregular governance triangle. CSR Russian style means that corporations prefer to communicate with the authorities instead of dealing with IOs; ie. the government speaks ‘on behalf’ of the indigenous communities and deliberately replaces the IOs in doing so. Today, strategic alliances with environmentalists have become a core element of IOs’ strategy to challenge the existing practice of their relations with corporations and force them into dialogue.

Izhma’s indigenous-environmental partnership started at the end of the 1980s and was formed by local Izhma activists from Izvatas and the grass-root environmental organization Save the Pechora Committee. If anything was exceptional in this strategic alliance, it was its deep ties at the local level, based on a shared sense of place, a common experience of powerlessness, and a desire for protection from extractiveled threats. The other distinguishing feature of the alliance was a closeness of ties between its leadership and Greenpeace. In contrast to other indigenous areas in the Arctic, Greenpeace has a strong positive public image in the Komi region, where the organization played a decisive role in bringing international attention to the catastrophic 1994 oil spill in Usinsk.62 The alliance’s ties with global environmental networks became even closer after a former activist at Save Pechora Committee joined Greenpeace Russia as head of its Energy Unit.63

The first big success of the alliance was a 2001 protest against transnational Pechoraneftegaz company plans to drill for oil in the Sebys nature conservation area, important hunting and ancestral lands for the Izhma-Komi and their herding routes. Despite the governor’s endorsement of the project, the case, with assistance from Greenpeace and other human rights organizations, was forwarded to court, which terminated all geological activities in Sebys.64 In 2004, the alliance repeated this success by opposing a planned project by the Siberian-Urals Aluminium Company (SUAL) to build an aluminum and bauxite plant in Izhma and Ukhta municipalities. The public campaign, which was covered by local and international media, culminated in 2005, when the alliance’s activists, dressed in Komi-Izhma traditional costumes, protested in front of the World Bank office in Moscow. Because of media attention and public pressure on all aspects of the project, including its potential investors, the SUAL was forced to postpone its development plans in the Komi.65 In 2008, the alliance successfully litigated Gazprom. The Russian energy giant faced a lawsuit for damage to pastures caused by construction of the Bovanenkovo-Ukhta gas transmission corridor, and paid compensation to the herders.66

Russia’s largest transnational private company, Lukoil, came to Izhma municipality in 2001 through its subsidiary, Lukoil-Komi, to develop the Makar’elskoye oil field. The Izhma community was in favor of Lukoil-Komi’s development plans, with high expectations for investment that would revitalize the economically depressed area, and hopes for a better future. Despite booming oil prices during the 2000s, the Izhma’s living standards saw little difference. The municipal budget remained heavily subsidized, while environmental, employment, migration, and demographic records demonstrate negative trends. The agreements between the municipality and Lukoil, designed in the ‘Russian style of CSR,’ lacked both transparency and the participation of local organizations, and, therefore, were perceived by the public as serving the interests of municipal authorities, rather than those of the community.

Due to regular oil spills and the company’s shortfalls in keeping its socio-economic and environmental promises, relations between the alliance and Lukoil soon turned sour.67 In 2012, these resentments and unresolved conflicts escalated into mass protests in Izhma municipality. The alliance demanded that Lukoil’s operations in the municipality be banned, as the company had failed to comply with obligations to consult affected communities before commencing its extractive activities. Over the next few years, local protests in Izhma, backed by Greenpeace, were followed by other public events, inside and outside of Russia, as described in the introduction of this article. Lukoil hired an entirely new team of ‘crisis managers’ to run the company’s operation and to protect its social license to operate (SLO) in ‘problematic’ Komi. For Lukoil, the conflict with Izhma-Komi, which was publicized by global NGO networks and international media such as Al Jazeera, had high reputational, economic and political stakes.

By strategically allying with environmentalists, through horizontal patterns of communication and exchange, Izvatas has received access to new resources (international networks, funding, information), previously not available to them. Owing to these resources, Izvatas has managed to utilize international ‘public noise’ in the negotiation process with Lukoil, forcing the company to recognize the Izhma community as a legitimate stakeholder regardless of the non-KMNS status of its residents. Furthermore, Izvatas leaders succeeded in forcing Lukoil to consider it as a legitimate negotiating partner that speaks on behalf of the community, and to sign a partnership agreement with Izvatas in 2015.

The agreement, however, marked the beginning of a split between Izvatas and its environmental allies. Driven by an ‘Arctic sanctuary’ agenda, the environmental groups criticized Izvatas for compromising with Lukoil. Since 2015, the relationship between Izvatas and its environmental allies continues to be strained over differences over their vision for community development and the tools needed to achieve sustainability.

5.3 Negotiating rights with oil company

Lukoil as a globally operated company, appears to place a strong emphasis on meeting international norms of responsibility and sustainability in its corporate, environmental and social activities. The company was the first among Russian oil companies to issue its own Social Codex (2002) and to sign on to the UN Global Compact (2006). In 2018, Lukoil issued the Strategy of Engagement with Indigenous Peoples (SEIP), which aims to ‘preserve the traditional way of living of the indigenous peoples in the territories of the company operations.’68 The SEIP emphasizes the company’s commitment to cooperate with indigenous peoples through multilateral and inclusive dialogue in accordance with international indigenous rights. Nevertheless, the SEIP considers indigenous peoples as stakeholders (along with the authorities, NGOs, and others) rather than indigenous rightsholders.69 These glossy reports aside, Lukoil is also known for its environmental misconduct records, especially in the Komi region.70

The company has partnership agreements with the regional authorities in the NAO and in the Komi, as well as separate agreements with each municipality wherein the company operates. These corporate payments to regional and local budgets are typically framed in terms of CSR, which covers everything from culture to education to health care to ecology. In 2017, the company’s social investments through CSR in the Komi Republic was estimated to be 2.5 billion RUB71 along with 4 billion RUB in NAO. In NAO,72 Lukoil also signs agreements on social-economic development with each reindeer enterprise. Spending for these purposes was 336.7 million RUB in 2007–2017.73

Nowadays, both Izhemskiy olenevod i Ko and Izvatas have direct stakeholder agreements with Lukoil-Komi on an individual and confidential basis. Izhemskiy olenevod i Ko signed its first agreement with Lukoil in 2006, after the cooperative registered in NAO. It is a ‘private-private’ type of agreement, concerned with the conditions under which the cooperative signs off its pasture lands to the company as a licensed industrial plot. The agreement opens with a memorandum of understanding, which is followed by its ‘financial part’. The financial part consists of a price tag that shows the price that the cooperative receives from the company as compensation for using its pastures and for disturbances caused to reindeer migration routes. The innovative aspect of the agreement is its recognition and stipulation of the cooperative’s right to use these payments at its discretion, either to cover annual operational costs or to invest them into future business developments. The design of the financial part of the agreement as a price tag is not a common practice among the herders. As Stammler and Ivanova (2016) argue, in contrast to the Komi reindeer cooperatives, cooperatives under Nenets’ leadership choose more in-kind services (i.e., snowmobiles, petrol, veterinary medicines, and forage for reindeer).74 Empirical data collected from Izhma herders in the Komi supports Stammler and Ivanova’s view that the Izhma herders are skilled negotiators and entrepreneurs. This claim, however, requires more in-depth and comparative analysis. The informants left without answering the question about the share of the company’s payments in the cooperative’s annual budget. Experts familiar with the situation in NAO have indicated that extractive payments could constitute up to 40%–50% of the cooperative’s annual budget, since numerous companies operate in the area and have signed agreements with them.75

Izvatas has a short history of signing agreements with Lukoil, which started in 2015. Designed as a ‘public-private’ agreement between the parties, it concerns the conditions under which the community provides Lukoil an SLO in the territory of the Izhma municipality. The agreement includes three groups of conditions set forth by Izvatas to Lukoil for obtaining an SLO. The first group refers to FPIC and aims to ensure that the interests and rights of Izhma local communities, including the right to reject industrial operations, are recognized and considered by the company before any extractive-related activities in the territory of the municipality. The second group concerns the financial support the company provides to fund activities to protect the Izhma-Komi language, culture, and traditions. For instance, the company co-funds the famous traditional festival Lud, a landmark social and cultural event for Izhma-Komi gathering several thousand participants from other regions of Russia and abroad. The third group refers to the company’s investments into development of local human capital. The company has funded several fellowships to talented Izhma-Komi youth at well-regarded Russian universities.76 At the time of this study, two-thirds of the annual budget of Izvatas came from the regional authorities’ grants via the nationalities’ policy channel. Previously engaged in international collaboration, nowadays Izvatas has no joint activities with partners abroad due to the recently restricted NGO regulations (e.g., foreign agent law).77 The backlash against IOs as ‘foreign agents’ has increased the value of Lukoil’s contributions to the budget of the organization.

Because of the confidentiality of the agreements both Izhma-Komi organizations have with Lukoil, there is little to say about how the content of these agreements or the negotiation process leading to them meets international standards and the company’s indigenous rights commitments. The analyses of the informants’ perceptions of the agreements with the company reveal four issues that the informants consider as crucial for their organizations. First, through a negotiating process with the company around compensations, the organizations get a chance to voice their priorities about investments and development paths they see as sustainable for their organizations and communities. By voicing these concerns, the organizations exert their agency, trying to make a difference in their constituents’ position economically, socially and symbolically. Second, for both organizations, the financial payments from the oil company contribute to financial diversification. In turn, this diversification of funding strengthens the organizations’ independence in relation to the authorities and increases the organizations’ symbolic status among similar civil society actors. Third, the informants perceive the company’s payments as highly controversial in terms of legitimacy, social equality, expropriation of common resources, and ecology. The informants largely expressed their concerns about the ability of these payments to promote sustainable development and cultural survival in the long-term. Fourth, many of the informants see their indigenous rights as compromised and negated by the rights they received as stakeholders.

6. Conclusion

The article traces the journey of two Izhma-Komi IOs across time and space to investigate the scope and influence of their agency to contest indigenous rights norms in the context of Russian oil development during the 2000s. The findings expand an understanding of the influence of the Izhma-Komi IOs’ agency (power) when it comes to indigenous rights norms and challenging these norms, despite the lack of state recognition of their constituents as KMNS. The study presents these IOs as co-producers of the localized version of common norms, showing that the Izhma-Komi’s normative understanding of indigeneity is informed by their local context, history, and other factors significant in their relationship with the state.

The analysis identifies three horizontal strategies the IOs applied to challenge the normative base of their constituents’ status and rights in the extractive context, including mobilizing through inter-indigenous recognition, alliancing with environmentalists and negotiating with an oil company. It shows how these strategies enabled the IOs to successfully change norms locally, in their relations with an oil company, and to ascertain certain rights and exert power previously not available to them. According to the analysis, the IOs’ strategies have become more informed, networked, strategic and pragmatic, absorbing both cooperation and conflicts.

The findings from the Izhma-Komi case study do not entail any claims for broader generalizations and conclusions. Nevertheless, they suggest trends, factors, and conditions that can impact IOs’ agency in their negotiations with extractive companies. The findings of the study suggest that despite the achievements made, the empowerment of these IOs, in their relations with oil companies, should not be overestimated. The agency of IOs to contest the normative base of their relations with the company depends on the willingness and receptivity of the company to negotiate. The latter rests on the company’s economic interests in the territory of operation, its ownership status, and integration into global markets. Lukoil has much at stake in the Komi in terms of finance, politics, and reputation. The company’s sensitivity to its image in global markets provided the Izhma-Komi IOs with tools to bargain over their stakeholders’ rights and to impose the international public leverage locally. Though more research is needed, in today’s context of ‘state capitalism’ in the energy sector, it is hypothetically unlikely that the outcomes for the Izhma-Komi would be similar, if they had to negotiate their rights with state-owned energy giants such as Rosneft or Gazprom.

As the analysis reveals, in order for IOs to achieve normative change when it comes to relations within the Russian ‘bad governance’ triangle, it is critically important for IOs to build coalitions with outside international actors such as indigenous and environmental organizations. A coalition with an outside actor can prove pivotal for a local IO to be recognized and accepted by a company as a potential partner for dialogue and negotiation. However, the Izhma-Komi-Greenpeace coalition demonstrates that the role of an outsider can also be controversial, highlighting biases within the Arctic IOs community itself. Assuming that indigenous-environmental alliances in the Russian Arctic are likely to increase, it can become more challenging for ‘young’ Russian IOs to internationalize their partnership with environmentalists and to benefit from such a partnership without strategical support from ‘mature’ Arctic IOs.

The durability and sustainability of the normative shifts in relations with the oil company achieved by the Izhma-Komi IOs, remain another concern. The issue is not limited to the informal and personalized character of the agreements signed. Lack of institutionalized mechanisms to enforce these agreements inevitably jeopardizes their durability from a long-term perspective. However, a more significant concern is what will happen with the Izhma-Komi after extractive activities in the region are over, given the limited period of oil projects, mostly between 20 and 50 years. The leaders of the Izhma-Komi IOs link their hopes for the future ‘after the big oil’ to the development of local ethnocultural tourism and promotion of reindeer products on the market, including export abroad.

The way in which the Izhma-Komi manage to maintain their lifestyle, culture and economic activities (traditional and innovative), will depend on the quality of the natural environment that the oil company leaves behind. While recognition of the Izhma-Komi as ‘stakeholders’ from the oil company is a step forward, it falls short of recognizing their rights as indigenous rights holders. Ultimately such recognition will depend on the Russian state and its constitutional and international commitments to indigenous peoples’ rights.

Acknowledgments

For critical comments on the drafts of this article, I would like to thank Else Grete Broderstad and Hans-Kristian Hernes. Thanks are also due to two anonymous reviewers, who provided valuable comments and feedback. The study described was funded by UiT The Arctic University of Norway – Research Fellow Scholarship (Kap.0281).

The article was completed in draft form when Nikolay Vasilevich Rochev, the chairman of Izvatas, died. With sincere respect and hope for a better future for the Izhma-Komi people, I dedicate this article to his work and memory.

Notes

- 1. Joint Statement of Indigenous Solidarity for Arctic Protection. Available at: https://intercontinentalcry.org/joint-statement-of-indigenous-solidarity-for-arctic-protection/ (accessed 29.11. 2018).

- 2. Anthony Speca, “Arctic Savior Complex.” Available at: http://www.northernpublicaffairs.ca/index/arctic-saviour-complex/ (accessed November 29.11.2018).

- 3. Nikolay Rochev, “Commentary: My Wish for Prosperity Without Oil. Russian Indigenous Leader Cautions Inuits about Resource Development.”Available at: http://www.nunatsiaqonline.ca/stories/article/65674my_wish_for_prosperity_without_oil/ (accessed 06.07.2018).

- 4. Interview, Izvatas, Izhma, March 2018.

- 5. Natalia Toporova, “V Ramkakh Vzaimouvazheniya” (‘As a part of Mutual Respect’), Severnye Vedomosti, 40(2015): 3.

- 6. Mannuel Castells, The Theory of The Network Society (MPG Books Ltd, Bodmin, Cornwall, 2006). Margaret Keck and Kathryn Sikkink, Activists Beyond Borders (Ithaca, NY & London: Cornell University Press, 1998).

- 7. James Anaya, “Indigenous Rights Norms in Contemporary International Law,” 8 Ariz. J. Int’l & Comp. L.1 (1991).

- 8. Natalia Yakovleva, “Oil pipeline construction in Eastern Siberia: Implications for indigenous people,”Geoforum 6(2011): 708–719; Florian Stammler and Aitalina Ivanova, “Confrontation, coexistence or co-ignorance? Negotiating human-resource relations in two Russian regions,” The Extractive Industries and Society, 3(2016): 60–72; Emma Wilson, “What is the social licence to operate? Local perceptions of oil and gas projects in Russia’s Komi Republic and Sakhalin Island,” The Extractive Industries and Society, 3 (2017): 73–81.

- 9. Indra Overland, Ranking Oil, Gas and Mining Companies on Indigenous Rights in the Arctic, (Drag: Arran Lule Sami Centre, 2016).

- 10. Joachim Habeck, What Means to be a Herdsman. The Practice and Image of Reindeer Husbandry among the Komi of Northern Russia (Munster: LIT Verlag, 2005); Yuri Shabayev and Valery Sharapov, “The Izhma Komi and the Pomor: Two Models of Cultural Transformation”, Journal of Ethnology and Folkloristics 5 (2011): 97–122; Hye Jin Kim, Yuri Shabayev and Kirill Istomin, “Lokal’naya gruppa v poiske identichnosti” (A Local Group in Search for Identity), Sotsiologicheskie issledovaniya, 8(2015): 85–92; Yuri Shabaev and Kirill Istomin, “Territorial’nost’, etnichnost’, administrativnye i kul’turnye granitsy: komi-izhemtsy (iz’vatas) i komi-permiaki kak “drugie” komi” (Territoriality, Ethnicity and Administrative and Cultural Borders: The Komi-Izhemtsy (Izvataz) and Komi-Permyak as the “Other” Komi), Etnograficheskoe obozrenie 4 (2017): 99–114.

- 11. Kim, Shabaev and Istomin, “Lokal’naya gruppa v poiske identichnosti”, 89–91; Shabaev and Sharapov, “The Izhma Komi and the Pomor,” 107–110; Sergey Sokolovsky, Politika Priznaniya Korennykh Narodov v Mezhdunarodnom Prave i Zakonodatel’stve Rossiyskoy Federatsii (“Politics of Indigenous Recognition in International Law and in the Russian Federation”) (Moscow: IEA RAN, 2016), 43–45.

- 12. Jan Kooiman et al. eds, Fish for life (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2005), 17.

- 13. Jan Kooiman, Governing as Governance (London: SAGE, 2003), 15.

- 14. Kooiman et al., Fish for life, 23.

- 15. Antje Wiener, “The Dual Quality of Norms and Governance beyond the State: Sociological and Normative Approaches to ‘Interaction,’” Critical Review of International Social and Political Philosophy, 10 (2007): 47–69.

- 16. Anthony Giddens, The Construction of Society: Outline of the Theory of Structuration (Cambridge: Polity Press, 1984), 9–16.

- 17. Giddens, The Construction of Society, 258.

- 18. Jakeet Singh, “Recognition and Self-Determination,” in Recognition versus Self-Determination: Dilemmas of Emancipatory Politics, ed. Avigail Eisenberg et al. (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2014), 50.

- 19. Singh, “Recognition and Self-Determination”, 59.

- 20. Nikolay Petrov and Alexey Titkov, Irregular Triangle: State-Business-Society Relations. (Moscow: Carnegie Moscow Center, 2010).

- 21. Petrov and Titkov, Irregular Triangle, 435.

- 22. Sergey Peregudov and Irina Semenenko, Korporativnoye Grazhdanstvo: Kontseptsii, Mirovaya Praktika i Rossiyskiye Realii (Corporate Citizenship), (Moscow: Progress-Tradition, 2008).

- 23. FZ-121 dated 20 July 2012 “O vnesenii izmeneniy v otdel’nyye zakonodatel’nyye akty Rossiyskoy Federatsii v chasti regulirovaniya deyatel’nosti nekommercheskikh organizatsiy, vypolnyayushchikh funktsii inostrannogo agenta” (On Amendments to Legislative Acts of the Russian Federation regarding the Regulation of the Activities of Non-profit Organisations Performing the Functions of a Foreign Agent). Available at: https://base.garant.ru/70204242/ (accessed 26.08. 2019); FZ-129 dated 23 May 2015 “O vnesenii izmeneniy v otdel’nyye zakonodatel’nyye akty Rossiyskoy Federatsii” (On Amendments to Some Legislative Acts of the Russian Federation). Available at: https://base.garant.ru/71035684/ (accessed 30.11. 2018).

- 24. Thomas Nilsen, “Artic-Based Russian NGO Labeled ‘Foreign Agent’ by Moscow,” Radio Canada International, April 24, 2017. Available at: https://www.rcinet.ca/eye-on-the-arctic/2017/04/24/arcticbased-russian-ngo-labeled-foreign-agent-by-moscow/ (accessed 26.08. 2019).

- 25. Izhma municipality web portal. Available at: http://www.admizhma.ru/ru/page/o_rayone_4.pasport_mr_izhemskiy (accessed 30.11. 2018).

- 26. Shabaev and Sharapov, “The Izhma Komi and the Pomor”, 101.

- 27. Habeck, What Means to be a Herdsman, 23.

- 28. Vitaly Kanev, Izvatas (Izhma,1991).

- 29. Igor Zherebtsov and Natalya Beznosova, Formirovaniye vneshnikh administrativnykh granits Komi avtonomii v XX veke (Formation of the external administrative boundaries of the Komi autonomy in the XX century) (Syktyvkar: Komi Science Center RAS, 2014), 13.

- 30. This is a modified map. The territory of the Komi Republic is marked by the blue frame. The map’s original: The Encyclopædia Britannica. Available at: https://media1.britannica.com/eb-media/30/2030-004-41A16422.jpg (accessed 15.07. 2019).

- 31. Brian Donahoe et al., “Size and Place in the Construction of Indigeneity in the Russian Federation,” 999.

- 32. Zherebtsov and Beznosova, Formirovaniye vneshnikh administrativnykh granits Komi avtonomii v XX veke, 44.

- 33. Habeck, What Means to be a Herdsman,76.

- 34. Yuri Shabaev, Mikhail Rogachev, Oleg Kotov, Etnopoliticheskaya Situatsiya na Territorii Prozhivaniya Narodov Komi (Ethnopolitical Situation in the Territories of the Komi Peoples’ Residence) (Moscow: Institute of Ethnology and Anthropology, the RAS, 1994).

- 35. Alexandr Etkind, Internal Colonization: Russia’s Imperial Experience (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2011).

- 36. Singh, “Recognition and Self-Determination”, 47.

- 37. FZ-82 dated 30 April 1999 “O Garantijah Prav Korennyh Malochislennyh Narodov Rossijskoj Federacii” (On the Guarantees of the Rights of Indigenous Small-Numbered Peoples of the Russian Federation). Available at: http://base.garant.ru/180406/ (accessed 30.11. 2018).

- 38. Order of the Government of the Russian Federation N 536-r dated 17 April 2006 “Ob utverzhdenii perechnya korennykh malochislennykh narodov Severa, Sibiri i Dal’nego Vostoka Rossiyskoy Federatsii” (On Approval of the List of Indigenous Peoples of the North, Siberia and the Far East of the Russian Federation). Available at: https://base.garant.ru/6198896/ (accessed 26.08. 2019).

- 39. Brian Donahoe et al., “Size and Place in the Construction of Indigeneity in the Russian Federation,” Current Anthropology, 49(2008): 1016; Similar ideas on the Russian politics of recognition, while without using the term of ‘moratorium’ expresses Sergey Sokolovsky, Politics of Indigenous Recognition in International Law and in the Russian Federation, 28–35, 43–52.

- 40. FZ-82 dated 30 April 1999 “O Garantijah Prav Korennyh Malochislennyh Narodov Rossijskoj Federacii”; FZ-104 dated 20 July 2000 “Ob Obschikh Printsipakh Organizatsii Obshchin Korrennykh Malochislennykh Narodov Severa, Sibiri i Dal’nego Vostoka” (On the general principles of organization of communities of indigenous small-numbered peoples of the North, Siberia and the Far East of the Russian Federation). Available at: https://base.garant.ru/182356/ (accessed 30.11.2018); FZ-49 dated 07 May 2001 “O Territoriyakh Traditsionnogo Prirodopol’zovaniya Korennykh Malochislennykh Narodov Severa, Sibiri i Dal’nego Vostoka Rossiyskoy Federatsii” (On the Territories of Traditional Nature Use of the Small-Numbered Indigenous Peoples of the North, Siberia and the Far East of the Russian Federation). Available at: http://base.garant.ru/12122856 (accessed 30.11.2018).

- 41. FZ-49 affords TTNU as a form of recognition to indigenous peoples’ land tenure rights.

- 42. FZ-104 defines Obshchina as ‘a special, a kinship or community-based organization of indigenous peoples, formed with a purpose to protect and develop traditional way of life, culture’ (Article 1). The legislator stipulates that operations of Obshchina’s have to be of a non-profit nature and must be limited by ‘traditional types of activities’ (Articles 5).

- 43. Vladimir Kryazhkov, Korennyye malochislennyye narody Severa v rossiyskom prave (Indigenous peoples of the North in Russian Law) (Moscow: Norma, 2010): 240–242, 244–253; Olga Murashko and Johannes Rohr, “The Russian Federation,”in IWGIA – The Indigenous World (Copenhagen: IWGIA, 2015): 30–39.

- 44. Phillipe Hanna and Frank Vanclay, “Human Rights, Indigenous Peoples and the Concept of Free, Prior and Informed Consent,” Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal, 31(2013): 146–157.

- 45. Vladimir Kryazhkov, “Legal Regulation of the Relationship Between Indigenous Small-Numbered Peoples of the North and Subsoil Users in the Russian Federation,” The Northern Review, 39(2015): 66–88.

- 46. Maria Tysiachniouk et al., “Oil Extraction and Benefit Sharing in an Illiberal Context: The Nenets and Komi-Izhemtsi Indigenous Peoples in the Russian Arctic,” Society and Natural Resources, 31(2018): 556–579; Natalia Novikova “Etnologicheskaya Ekspertiza v Akademicheskom Diskurse i Ozhidaniyakh Korennykh Narodov” (Ethnological Expert Review: Academic Discourse and Indigenous People’s Expectations), Arktika: Ekologiya i Ekonomika, 1(2018): 125–135.

- 47. Decree of the President of the Russian Federation N 296 dated 2 May 2014 “O sukhoputnykh territoriyakh Arkticheskoy zony Rossiyskoy Federatsii” (On land territories of the Arctic zone of the Russian Federation). Available at: https://base.garant.ru/70647984/ (accessed 26.08. 2019).

- 48. Valeri Zhuravel, “Prava Korennykh Narodov v Rossiyskoy Arktike” (The Rights of Indigenous Peoples in the Russian Arctic), Arktika i Sever, 30(2018): 76–95.

- 49. Habeck, What Means to be a Herdsman, 10–15.

- 50. Interview Izhemskyi Olenevod, Sizyabsk, March 2018.

- 51. Habeck, What Means to be a Herdsman, 114

- 52. Johnny-Leo Jernsletten and Konstantin Klokov, Sustainable Reindeer Husbandry (Centre for Saami Studies University of Tromsø, 2002).

- 53. The Republic of Sakha (Yakutia) was the first Russian region that passed the regional law on reindeer husbandry in 1997. In 1998, the Yamalo-Nenets AO and the Chukchi AO in 2000 also issued regional laws on reindeer husbandry.

- 54. Florian Stammler and Vladislav Peskov, “Building a ‘Culture of Dialogue’ among Stakeholders in North-West Russian Oil Extraction,” Europe- Asia Studies, 60 (2008): 831–849.

- 55. Interviews Yasavey, Moscow, November 2018; Interview Saint Petersburg State University, St. Petersburg, May 2018.

- 56. Interview Izvatas, Mokhcha, March 2018.

- 57. RAIPON has its representatives at the Russian Presidential Council on Interethnic Relations, the Russian Government; it is one of the permanent participants of the Arctic Council, the Arctic Economic Council and with a consultative status at the UN Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) and the UN Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues.

- 58. Interview Izvatas, Mokhcha, March 2018.

- 59. Interview Center for Support of Indigenous Peoples of the North via Skype, October 2018.

- 60. Peregudov and Semenenko, Corporate Citizenship, 2008.

- 61. The UN Global Compact (2004), Global Reporting Initiative, Sustainability G4 (2013), International Petroleum Industry Environmental Conservation Association (IPIECA) on voluntary sustainability reporting (2015).

- 62. Kirsti Stuvoy, “Human Security, Oil and People,” Journal of Human Security 7(2011): 5–19.

- 63. Interviews Save Pechora Committee, Izhma – Syktyvkar, March 2018.

- 64. Interviews Save Pechora Committee, Izhma – Syktyvkar, March 2018.

- 65. Interviews Save Pechora Committee, Mokhcha- Syktyvkar, March 2018.

- 66. Interview Izhemskyi Olenevod, Sizyabsk, March 2018.

- 67. Interviews Izvatas, Save Pechora Committee, Izhma – Syktyvkar, March 2018.

- 68. Lukoil, Preserving the traditions of the North.

- 69. Lukoil, Preserving the traditions of the North.

- 70. Ellie Martus, Russian Environmental Politics (London and New York: Routledge, 2018).

- 71. News release, web portal Neftegaz.ru. Available at: https://neftegaz.ru/news/view/169297-LUKOYL-tsenit-komfortnyj-investklimat-v-Komi.-V-2018-g-kompaniya-uvelichit-vlozheniya-v-sotsialnye-proekty-v-regione-v-15-raza (accessed 23.01.2019).

- 72. News release, official web of the Administration of NAO. Available at: http://adm-nao.ru/press/governor/18628/ (accessed 23.01.2019).

- 73. Lukoil, Preserving the traditions of the North (Lukoil, 2018). Available at: http://www.lukoil.ru/Responsibility/SocialInvestment/HighNorthPeoplesSupport (accessed 23.01.2019).

- 74. Stammler and Ivanova, “Confrontation, coexistence or co-ignorance?”, 68.

- 75. Interview, RAIPON, Moscow, November 2018.

- 76. Interview Izvatas, Izhma, March 2018.

- 77. Tor Gjertsen and Greg Halseth, eds., Sustainable Development in the Circumpolar North. From Tana, Norway to Oktemtsy, Yakutia, Russia. The Gargia Conferences for Local and Regional Development (2004–14) (Tromsø: UiT/The Arctic University of Norway and Prince George: The Community Development Institute at University of Northern British Columbia, 2015), https://www.unbc.ca/sites/default/files/sections/community-development-institute/ebookgargia2004-2014-eddec42014withchdois.pdf (accessed August 19, 2019).