The Arctic has often been described as a zone of peace and cooperation.1 This description is not without merit: During recent “cold spells” in Russian-Western relations—as in the aftermath of the 2008 Russo-Georgian war—the Arctic states have managed to bracket off their Arctic policy from general East-West relations. But what of the current crisis between Russia and the West following Russia’s annexation of Crimea and subsequent involvement in Eastern Ukraine? Since 2014, relations between Russia and the West have been plummeting; never since the breakup of the Soviet Union has the situation between Moscow and Washington and other Western capitals been more strained. Indeed, many observers have described this as approximating a new Cold War, or at least a Cool War.2 The longer this situation persists, the more likely are potential spillovers to the Arctic. We must ask: Can co-operative Russian and Western Arctic policies survive the present crisis?

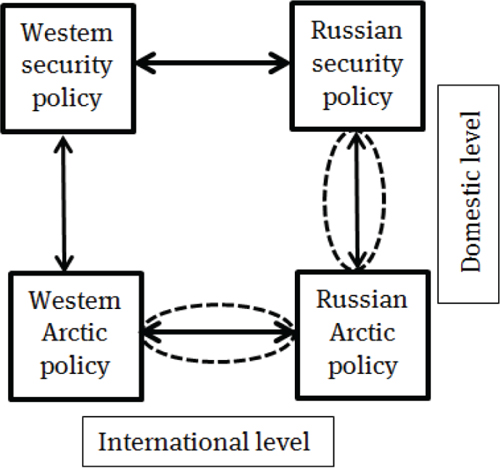

This thematic cluster of articles discusses how the current crisis in relations between Russia and the West may influence the levels and forms of cooperation in the Arctic in the years to come. Until recently, the Arctic has stood out as a special zone where Russia could engage in practical cooperation even with actors with whom relations were otherwise more strained.3 The literature has tended to portray the Arctic as either a new “promised land”—or an area of potential confrontation.4 Shunning simplistic characterizations, we seek to take the discussion one step further by analyzing Russia’s approach to the Arctic (and the approaches of the other Arctic states) as the product of a dynamic “two-level game”5 involving domestic factors as well as interaction with other states.

Applying a two-level analytical framework, we aim to fill important gaps in existing research on the Arctic: First, while several studies have taken a comprehensive approach to Russian Arctic policy,6 we offer new insights into the process of policy formulation, in particular the interaction between regional and central interests. Putin is widely seen as all-powerful in Russian policymaking. However, even in autocratic systems like that of today’s Russia, policy is likely to be attuned to influential domestic ideas, actors and institutions—especially when the legitimacy of the regime has been built on empowering certain institutions and/or on incorporating views dominant in the domestic sphere.7 We explore how domestic stakeholders, often with conflicting interests, succeed in shaping Russia’s Arctic policy.

Second, by studying the impact of the interaction between Russia and Western countries on the formulation of Russian Arctic policy, we provide new insights into international relations in the Arctic, as well as the broader field of Russian security studies. Whereas much of this latter literature has analyzed Russian security policy in isolation from domestic politics as well as from the security policies of other states, we have chosen a more relational approach.8 For example, if the Western Arctic powers come to view the Arctic as primarily an arena for state-contestation and security, this will, we argue, play into and shape Russian policies. Recognizing that one state’s security policy and internal politics are not formulated in isolation from the policies of other states, we adopt an interaction perspective to show how Moscow’s Arctic policy priorities and relations with the West fluctuate.

We thus seek to overcome two typical shortcomings in analyses of Russian policymaking: the tendency to treat Russia as a monolithic actor, and the failure to take into account the significance of Russia’s interaction with other actors.

Within the broader field of Russian foreign-policy studies this cluster of articles contributes to the literature on how dominant and changing ideas inform and influence Russian foreign policy.9 The authors analyze Russian—as well as Norwegian—policies on the Arctic through the prism of three ideal-typical modes of policy, which capture ideational positions as well as specific policies and actions.

The realist mode is driven by overall security interests and attention to the distribution of military power. According to this mode, a state which views itself as a great power in military terms will privilege security concerns in foreign policy, regardless of policy area.10 This ideational position finds practical expression in actions like increasing defense expenditures, prioritizing security over economic development, and undertaking various forms of military posturing.

In the institutionalist policy mode, the emphasis is on international regimes, institutions and rule-based cooperation with other states.11 A state acting primarily within this foreign-policy mode would downplay security concerns, and even pursue comprehensive and committed institutional collaboration in the area of security policy. In policy formulation, this ideational position may find expression in actions like increasing the resources allocated to multilateral collaborative institutions and regimes, or introducing new initiatives aimed at strengthening cooperation (in this case, in the Arctic).

These two modes are well-known. We also introduce a third mode inspired by recent works on diplomacy: the diplomatic management mode,12 located somewhere in-between the first two. Here foreign policy is not shaped by security interests alone, but is characterized by careful adjudication between different courses of action within various policy areas. For example, Russia may be at loggerheads with the West over Ukraine and Syria—but that might make it even more important to maintain zones of cooperation on other fronts, including the Arctic. In practical politics, this ideational position can be translated into, for example, greater military posturing in the Arctic alongside intensified communication and cooperation initiatives.

The articles in this cluster utilize the three modes to categorize statements, policies and actions on the Arctic by various Russian domestic actors and institutions, as well as by the Norwegian authorities (the latter as a proxy for “the West”). By covering the years 2012–2018 (Putin’s third presidential term) we can treat the pre-Ukraine crisis situation as a baseline.

The analysis is presented in a series of four articles to be published consecutively, covering topics ranging from domestic Russian Arctic policy formulation to foreign policy and international exchanges.13 Starting from the domestic agenda, Helge Blakkisrud has studied the role of State Commission for Arctic Development. This Commission was set up in 2015 to serve as a platform for coordinating the implementation of the government’s ambitious plans for the Arctic, for exchange of information among Arctic actors, and for ironing out interagency and interregional conflicts. Based on the case study, Blakkisrud argues that the image of a Russian governance model based on a strictly hierarchic “power vertical” must be modified: Russia’s Arctic policy formulation is marred by infighting and bureaucratic obstructionism.

In the next contribution, Jakub M. Godzimirski and Alexander Sergunin discuss how Russian thinking about the Arctic has evolved in recent years, situating current Russian expert and official narratives on the Arctic within the broader context of the debate on Russia’s place in the international system. Specifically, they investigate how various schools of thought influential in shaping Russian foreign and security policy have framed Arctic questions and positions. From official statements on the Arctic, they find that Russia’s current Arctic policy is influenced by both neorealist and neoliberal ideas, whereas the more idiosyncratic and often-cited “Russian exceptionalism” has little real bearing on policy formulation.

In the third article, Pavel Baev examines Russia’s “ambivalent revisionist/status-quo policies” in the Arctic, outlining the simultaneous pursuit of preserving cooperation with Western neighbors and commitment to building up own strength. Baev identifies four Russian Arctic interest domains: nuclear/strategic, geopolitical, economic/energy-related, and symbolic. Across and within these domains he finds traces of the three different policy modes as well as of status quo and revisionist thinking, but concludes that, within the timeframe in focus, it is the revisionist tendencies that have been gaining ground.

The final contribution to this article cluster, co-authored by Julie Wilhelmsen and Kristian Lundby Gjerde, focuses on international interaction in the Arctic. The authors systematically examine changes in the discourse on Self and Other in Russian and Norwegian official statements, to establish what kind of policy mode characterizes official discourses in the years immediately prior to and after the Russian annexation of Crimea. Noting how the changing mode of the one state affects that of the other, they find that realist-mode policies increasingly dominate on both sides. As a result, they argue, a New Cold War is now spreading to the Arctic.

Helge Blakkisrud*

Guest Editor

NOTES

- * The text has been emended to reflect changes made to the series’ publication plan after this article was published on 19 December 2018.

- 1. See, for example, Geir Hønneland and Olav Schram Stokke, eds, International Cooperation and Arctic Governance: Regime Effectiveness and Northern Region Building (Routledge: London, 2006); Kristian Åtland, “Russia and Its Neighbors: Military Power, Security Politics, and Interstate Relations in the Post-Cold War Arctic,” Arctic Review on Law and Politics, 1 (2) (2010): 279–298; Oran Young, “The Future of the Arctic: Cauldron of Conflict or Zone of Peace?” International Affairs 87 (1) (2011): 185–193; Valery Konyshev and Aleksandr Sergunin. “The Arctic at the Crossroads of Geopolitical Interests,” Russian Politics and Law 50 (2) (2012): 34–54; Andreas Østhagen, “High North, Low Politics—Maritime Cooperation with Russia in the Arctic,” Arctic Review on Law and Politics 7 (1) (2016): 83–100.

- 2. Robert Legvold, “Managing the New Cold War: What Moscow and Washington Can Learn from the Last One,” Foreign Affairs, (July/August) (2014): 74–84; F. Stephen Larrabee, Peter A. Wilson and John Gordon IV, The Ukrainian Crisis and European Security: Implications for the United States and U.S. Army (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2015).

- 3. See, for example, Lassi Heininen, Alexander Sergunin and Gleb Yarovoy, Russian Strategies in the Arctic: Avoiding a New Cold War (Moscow: Valdai Club, 2014); Alexander Sergunin and Valery Konyshev, “Russia in Search of its Arctic Strategy: Between Hard and Soft Power?” The Polar Journal, 4 (1) (2014): 2–19; Elana W. Rowe and Helge Blakkisrud, “A New Kind of Arctic Power? Russia’s Policy Discourses and Diplomatic Practices in the Circumpolar North,” Geopolitics, 19 (1) (2014): 66–85.

- 4. Oleg Aleksandrov, “Labirinty arkticheskoi politiki,” Rossiya v global’noi politike, (4) (2007): 114–123; Margaret Blunden, “The New Problem of Arctic Stability,” Survival, 51 (5) (2009): 121–141; Charles Emmerson, The Future History of the Arctic (New York: Public Affairs, 2010); James Kraska, ed., Arctic Security in an Age of Climate Change (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011); Christian Mière and Jeffrey Mazo, Arctic Opening: Insecurity and Opportunity (London: Routledge, 2013).

- 5. Robert D. Putnam, “Diplomacy and Domestic Politics: The Logic of Two-level Games,” International Organization, 42 (3) (1988): 427–460.

- 6. See, for example, Helge Blakkisrud and Geir Hønneland, eds, Tackling Space: Federal Politics and the Russian North (Lanham, MD: University Press of America, 2005); Marlene Laruelle, Russia’s Arctic Strategies and the Future of the Far North (Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, 2014).

- 7. Henry E. Hale, Patronal Politics: Eurasian Regime Dynamics in Comparative Perspective (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014).

- 8. This approach has been advocated by, among others, Ted Hopf, Social Construction of International Politics: Identities and Foreign Policies, Moscow 1955 and 1999 (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2002); Andrei P. Tsygankov, “Russia in the Post-Western World: The End of the Normalization Paradigm?,” Post-Soviet Affairs, 25 (4) (2009): 347–369; Julie Wilhelmsen, “Russia and International Terrorism: Global Challenge—National Response?” in Russia’s Encounter with Globalization: Actors, Processes and Critical Moments, eds. Julie Wilhelmsen and Elana Wilson Rowe (London: Palgrave Macmillan), 97–133; Aglaya Snetkov, Russia’s Security Policy under Putin: A Critical Perspective (London: Routledge, 2015).

- 9. Hopf, Social Construction of International Politics; Tsygankov, “Russia in the Post-Western World;” Jeffrey Mankoff, Russian Foreign Policy: The Return of Great Power Politics (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2011); Aleksandr Kubyshkin and Aleksandr Sergunin, “The Problem of the ‘Special Path’ in Russian Foreign Policy (from the 1990s to the early Twenty-first Century),” Russian Politics and Law, 50 (6) (2014): 7–18.

- 10. John J. Mearsheimer, The Tragedy of Great Power Politics (New York: Norton, 2001); John J. Mearsheimer, “Why the Ukraine Crisis Is the West’s Fault,” Foreign Affairs, 93 (5) (2014): 77–89.

- 11. Stephen D. Krasner, International Regimes (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1983); James N. Rosenau and Ernst-Otto Czempiel, Governance without Government: Order and Change in World Politics (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992); John Ruggie, Constructing the World Polity: Essays on International Institutionalization (London: Routledge, 1998).

- 12. Paul Sharp, Diplomatic Theory of International Relations (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009); Ole Jacob Sending, Vincent Pouliot and Iver B. Neumann, eds, Diplomacy and the Making of World Politics (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015).

- 13. All articles have been written within the context of the RCN-funded research project “Can co-operative Russian and Western Arctic policies survive the current crisis in Russian–Western relations?” (CANARCT) (project number 257638).

- * Senior Researcher, Norwegian Institute of International Affairs (NUPI).