1. Introduction

Since the Ukraine crisis erupted in 2014, Russian–Western relations have plummeted dramatically. Despite the different historical setting, there are striking similarities to the Cold War, one being that the globally interlinked nature of that conflict meant that “trouble in one area metastasized to others.”1 The standoff over Ukraine has already obstructed cooperation across various issues. Could it also affect state interaction between two countries in the Arctic—a region that has in recent decades been defined primarily by a culture of compromise2 or a spirit of cooperation?3 This article examines changes in the premises of Norwegian and Russian state interaction in the Arctic: how official views and narratives have changed before and after the crises in Ukraine, 2012–2016.4 What kind of policy mode—“realist,” “institutionalist,” or “diplomatic management” (see introduction to this thematic cluster)—characterizes Norwegian and Russian official discourse? How have changes in policy mode affected interaction between these two Arctic states?

Even during the Cold War, with security concerns in focus, a culture of compromise was achieved by balancing policies undertaken in the realist mode with those pursued in the diplomatic management mode. Seeking to understand the premises for interaction between Norway and Russia in the Arctic, we ask whether Norway has kept this balance in the period 2012–2016—and which modes characterize Russia’s approach toward Norway during the same period. We conclude with a discussion of how the changing policy modes of the one state have affected changes in the other.

The article offers two contributions: to the current public debate, and to the academic debate on Russian–Western relations. First, we challenge the widespread assumption that states have unchanging, set modes of foreign policy: that Western states are necessarily “cooperative,” whereas Russia, reverting to its “true self,” is necessarily “assertive.” Second, emphasizing how the character of relations is determined not solely by the foreign policy of one state, but by the combination of the foreign policies of several states, this article expands the academic literature on Russian–Western relations in the Arctic and beyond in the wake of the Ukraine crisis. A more nuanced understanding of Arctic interactions between Norway and Russia can help to explain the extent to which—and how—the crisis in Russian–Western relations is “contaminating” the Arctic.

We study Norway’s changing approach to Russia in particular detail, for several reasons. First, this article is part of a thematic cluster where other contributions cover various aspects of Russian policies in the Arctic in depth. Here, we aim to show how the policies of even a small state like Norway can interact with and play into the policies of Russia in the Arctic. Second, Norwegian government officials are far more preoccupied with Russia than Russia is with Norway, and thus talk about Russia to a much greater degree. This reflects the core identities of these two states, their representations of Self and Other, and the status of the Arctic in official national discourses. We have selected the period 2012–2016—two years before and two years into the crises in Ukraine—to capture the consequences of these landmark events in a totally different theatre: the Arctic.

We begin by presenting our understanding of states and foreign policies, as well as our sources and how we apply them to address our research questions. Drawing on secondary sources, in section 3 we offer a brief historical survey of the types of policy modes used by Norway and Russia in the Arctic. Sections 4 and 5 present our analyses of Norwegian and Russian official texts. These sections show the changing narratives of Self and Other in the Arctic and discuss the policy modes involved. In the concluding section, we note that the new Russia–West conflict, exacerbated by the 2014 crises in Ukraine, has already contaminated interaction in the Arctic; and, with reference to the combination of changing Self/Other representations and policy modes on both sides, we indicate how this came about.

2. Theory, methodology and analysis of texts

We view states not as pre-constituted political entities, but as constantly in the making.5 State identities are deeply relational and continuously reproduced through social interaction.6 Admittedly, the relative consistency of state identities can be remarkable.7 Russia, for example, has a “great power” identity: it often views and acts in the world by projecting power and seeing any gain for other states as a loss for itself. But Russian identity is not constant, nor is Russia’s foreign policy practice.8 Norway is a small state with a foreign policy identity that often makes it inclined to support international legal regimes, multilateral institutionalism, cooperation, and compromise.9 But also Norway changes, and realist policies are not unheard-of. Such changes may occur in response to an assertive Russia, or to pressure from an assertive ally, or because Norway is re-defined from within. Whatever it is that triggers the change in a state’s identity articulations, we assume that such narratives of Self and Other lay out logical paths for policies and inform the policy mode involved.10 Political statements cannot be dismissed as mere “rhetoric”: they shape policies and patterns of state interaction in fundamental ways.

This study builds on in-depth, systematic scrutiny of official statements and documents. The Norwegian data are statements, press releases, speeches etc. from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA), the Prime Minister’s Office, and the Ministry of Defense (MoD). The Russian data are transcripts and statements from the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs (including the Minister’s and Deputy Ministers’ public appearances, transcripts from press briefings, “answers to the press,” and official statements and “comments”), transcripts from the public appearances of the President, and news documents from the Ministry of Defense. The texts have been “scraped”—downloaded in full—from www.regjeringen.no and www.mid.ru, www.kremlin.ru, and www.mil.ru, respectively, and organized in a readily searchable table with full text of each document together with metadata (date, type of document, etc.).

We then narrowed down our text collection to documents that include references to both Russia and the Arctic on the Norwegian side, and documents that include references to Norway or the Arctic on the Russian side—the difference being due to the far higher number of documents on the Norwegian side.11 We hold that the resulting text collection allows us to trace salient trends in the official discourse on both sides in the period under study.

Having the text selection available in such an organized manner significantly eased the process of data management. Further, having complete text collections from which to select the subset allowed us to contextualize the attention given to the subject in official discourse over time.

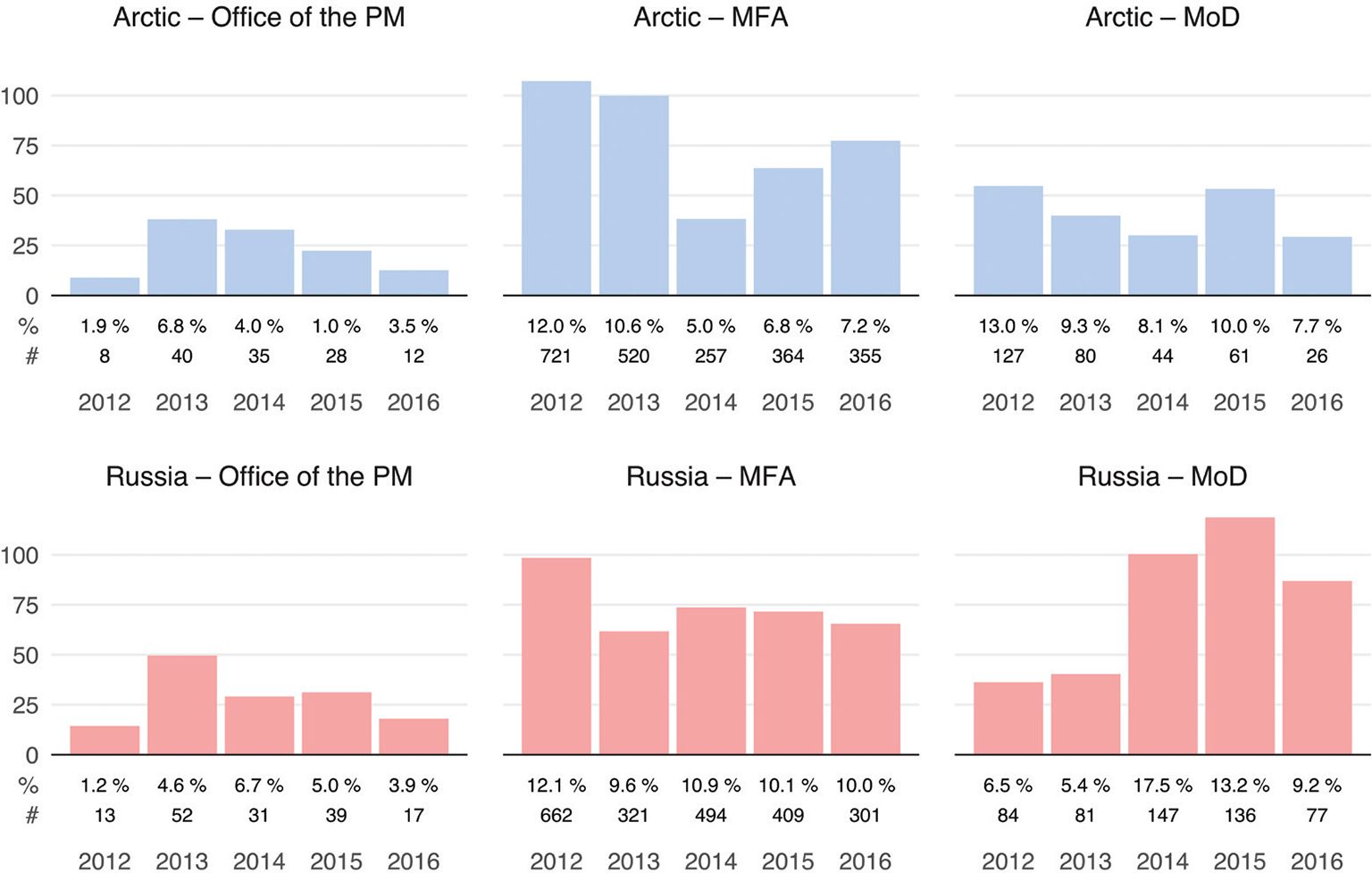

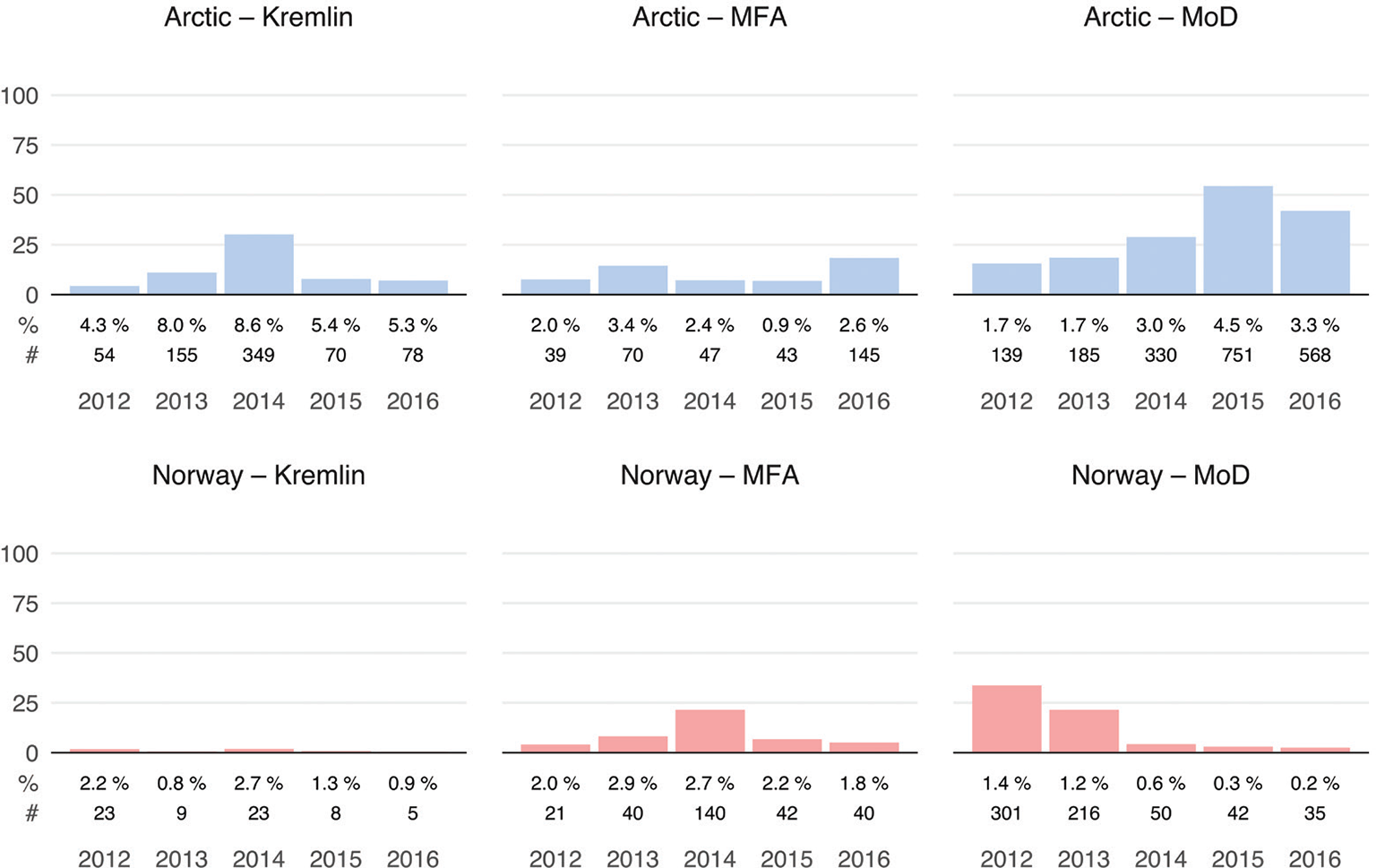

The bar charts in Figure 1 show the frequency of mentions of the Arctic and Russia(n) in Norwegian official discourse for the period 2012–2016, measured as number of mentions per 100,000 words in the documents of the three ministries.12 Two additional measurements are included below the bars for each year: the percentage of documents in which the terms are mentioned, and the total number of mentions per year. Figure 2 displays the corresponding frequency of mentions of Norway and the Arctic in Russian official discourse.13

While Figure 1 and Figure 2 are not directly comparable (due, inter alia, to differing press and information policies), they show that Norway talks much more about Russia than Russia talks about Norway, and indicate trends within the different ministries. On the Norwegian side, the most striking trend is that, from 2014, the MoD mentions Russia far more frequently. For the MFA, the extent—if not content—of attention has been fairly stable. On the Russian side, two trends in the press documents from the Russian Ministry of Defense stand out: the frequency of mentions of Norway drops drastically from 2014, a direct result of Norway suspending military cooperation and joint exercises with Russia; and the frequency of references to the Arctic increases significantly.14

To trace the development of the policy modes at play in the Arctic, we examine the content of this attention in depth. Through discourse analysis, we uncover how the “Arctic” is represented in these texts; how each state represents its own role, interests, and intentions in the region, as well as how the role, interests, and intentions of the other are represented. In line with the meta-theoretical foundation of discourse analysis, our analysis does not allow us to draw conclusions as to what the true “intention” of these states might be.15 We take the written and spoken words of official representatives at face value and establish the representations of Self and Other. Special attention is paid to how these narratives on relations in the Arctic shift over time and across issue areas. This makes it possible to establish the policy modes of the two states 2012–2016, and the prospects for New Cold War contamination. We begin by drawing a rough picture of the changing modes of Norwegian–Russian interaction in the period prior to the years in focus here.

3. Norway and Russia in the Arctic: historical mix of modes

Even during the Cold War, various modes were at play in the Arctic, although security concerns were central.16 Norway pursued deterrence through NATO membership and limited cross-border collaboration in the North. These policies, which can be seen as being pursued in a realist mode, given the primacy afforded to security interests and power projection, were paralleled on the Russian side.17 Still, the priority given to security issues on both sides was complemented by policy initiatives aimed at reducing tension and balancing between security and other issue areas, indicating that policies were pursued also in a diplomatic management mode. On the Norwegian side, deterrence policies were matched by policies of reassurance. Norway’s “self-imposed restraints” were aimed at alleviating Soviet concerns of Western aggression.18 In addition to regular diplomatic contacts, Norway and the USSR sought to develop bilateral management measures for the fish resources in the Barents Sea.19 Also the lengthy negotiations over the delimitation line in the Barents Sea starting in the early 1970s can be seen as part of a diplomatic management mode of policy, as they prevented the issue from being securitized in the public debate and located it outside the orbit of East–West confrontation.

With the end of the Cold War, Norway sought to strengthen the multilateral institutional structures in the North, including international legal regimes, and to promote interaction with Russia in these committing and potentially transforming institutional structures. A major Norwegian effort was the initiation of the Barents Euro-Arctic Council in 1993. Work focused on toning down the importance of security issues, alleviating military tensions, and enhancing trust and prosperity through cross-border activity in the economic, cultural, environmental, health, and educational spheres.20

However, to say that Cold War realist thinking was replaced by post-Cold War institutionalism would be an oversimplification—of both eras. For example, although Norwegian policies were redirected away from deterrence, and other policy fields than security were allowed to dominate, Norway’s rejection of Russia’s suggestion in the early 1990s to incorporate security into the Barents Cooperation constituted a silent but significant continuation of security-oriented, realist thinking. Tweaking the self-imposed restrictions from the Cold War era, Norway also encouraged increased allied presence in the North and sought to attract continued strategic attention to the region.21 And while Russia did take part in this new institutionalism, to some extent Moscow saw the institutions Norway initiated in this period as skewed—not neutral international institutions, but tools in a realist-oriented policy of power projection.22

In general, however, Moscow neglected the Arctic region in the 1990s. This changed after the turn of the millennium, due to rising Russian capacities, the re-emergence of the Northern Sea Route, the possibility of extracting Arctic oil and gas,23 and the “impending division of the Arctic continental shelf,” to be conducted in accordance with the UN Convention on the Law of the Seas (UNCLOS).24 The economic prospects these developments offered, as well as the general focus on Russian reform through integration with Western economies and global institutions, inclined Russia’s approach to Norway in the North more toward the institutional and diplomatic management modes—evident, for example, in Russian policies on Svalbard.25

This Russian approach corresponded with a renewed Norwegian emphasis on institutionalism from 2005 onwards. The new Labor–Center–Socialist coalition made the “High North” a national priority; collaboration and partnership with Russia became crucial.26 The new High North initiative stressed the spheres of science and business, and welcomed the prospects for Norwegian participation in developing the Shtokman gas field. It also involved the continuation of collaborative efforts across issue areas like the environment, climate, nuclear security, fisheries, and people-to-people contact. In addition, Norway sought to enhance multilateral institutional cooperation through engagement in the Arctic Council and in global issues like climate and indigenous rights.27

The landmark 2010 Norwegian/Russian agreement on the delimitation line in the Barents Sea, dividing the contested area evenly in two, can be seen as the fruit of a culture of compromise logically emerging from state interaction imprinted by an institutionalist mode of policy.28 Arguably, such a culture could thrive because the region was not made an arena for security-oriented big-power politics and zero-sum thinking.

The predominance of a culture of compromise at this point does not mean that other modes were not present, however. Leif C. Jensen, for example, argues that Norwegian politicization of energy issues made the energy game into “high politics” and contributed to the rebirth of realism and state-centrism in the region.29 In the years prior to the start of our case study there were also Norwegian efforts to bring NATO “back home” to prioritize the territorial defense of member states, efforts that contributed to the renewed emphasis on territorial defense in NATO’s 2010 Strategic Concept.30

On the Russian side, reactions to the 2010 delimitation agreement were split, showing different views of “Norway” and “Russia” in the Arctic and the type of approach to be pursued. As noted by Geir Hønneland, there were two camps here: what we can call a “bad agreement camp,” which felt that Russian territories and interests had been sacrificed and saw the treaty as an expression of Russian weakness in the face of Western countries conspiring against Russia; and what we can call a “good agreement camp”, which saw the treaty as an expression of and a contribution to good-neighborly cooperation, and dismissed the idea that Norway intended to trick or fool anyone.31 Another conceptualization of Russian approaches to the Arctic in general is offered by Marlene Laruelle, who identifies two Russian Arctic strategies: “security first” and “cooperation first.”32 Although Hønneland’s and Laruelle’s categories do not fully overlap, the “security first” and the “bad agreement” readings share a realist reading of international politics, whereas the “cooperation first” and “good agreement” readings have more in common with a “liberalist institutionalist” outlook.

The key point here is that Russia has approached the Arctic and relations with Norway in various ways across different issues, changing over time. Also on the Norwegian side, approaches to Russia have been more mixed than is often recognized. This provides our point of entry for the case-study below: it is not the policies of one state alone that determine what kind of relations will dominate in the Arctic. Cooperative or conflictual relations, understood more as a scale than a dichotomy, emerge through the combination of changing foreign policies and how these policies are perceived by the other side.

4. How Norway views Russia in the High North

4.1. From key partner in the land of opportunity to potential challenge, 2012–2013

Our review of official texts from 2012 shows representations of the Arctic/High North as a land of opportunity and collaboration. “Energy-enthusiasm,” “sustainability,” “knowledge,” “international law,” “peace,” “development,” “technology,” “engagement,” “increasing activity,” “global interaction,” “institutions,” “collaboration in military sphere,” and “success” are repeated words. In this space of positive dynamics, the Russian Other features as a key partner in positive terms, and as an actor who respects the law.33 Norwegian–Russian relations had “never been better than now.”34 Even in policy areas where Russia is represented as a “challenge,” collaboration is to be the solution.35 Russia’s human rights and democratic credentials (or lack thereof) are not emphasized until late 2012/early 2013. Norwegian Foreign Minister Jonas Gahr Støre stated explicitly that such credentials could not be used to question the legitimacy of Russia as an actor on the international arena. The collaborative line would continue, also after the controversial 2011 and 2012 Russian elections.36

The discourse on collaboration and partnership with Russia is pursued together with a low-key but continuous emphasis on the need to strengthen territorial defense in the North, as well as to draw the attention of NATO and Norway’s closest allies to the region. The main priority for Norwegian defense in this period is to “constitute a war-preventive threshold on the basis of NATO membership.”37 However, reflecting the primacy of the institutionalist mode in Norwegian policies toward Russia in the North, these security policy considerations are never explicitly linked to Russia, not even in MoD speeches; in official discourse more generally, the North remains a special space regulated by law and peaceful collaboration. When heightened Russian military activity in the North is mentioned, this is represented as a “legitimate” return to the “normal.”38 During a visit by Russian Deputy Minister of Defense Anatolii Antonov, where military collaboration was on the agenda, Norwegian officials even suggested, “We will become world champions in defending the High North, on both sides of the border.”39

Seen from the outside, the mix of the policies of “institutionalized partnership with Russia in the North” and a “strong NATO in the North” constitutes a clear tension in the Norwegian approach. It is also a mix certain to elicit less cooperative policies from the Russian side if the second were accentuated at the expense of the first, and Russian views of NATO became more adversarial. Oddly, the idea of “traditional security policy” or a “stable military presence” in the North as a condition for good-neighborly relations is floated in 2012, perhaps in an attempt to bridge the two incompatible lines of Norwegian policy in the North.40 And, at least in MoD texts, we note rising apprehension of Russia’s growing “big-power ambitions” as well as the “modernization” and “buildup” of its military, indicating that Norwegian representations and views of the Russian Other are changing in response to Russian actions.41

During autumn 2012/spring 2013 we see new apprehensions concerning Russia in official Norwegian statements concerning NGOs in Russia and Moscow’s turn to “authoritarian” rule.42 Importantly, this new focus on Russia’s human rights and democracy credentials seems to tie in with the broader framing of global developments identifying the “West” and the “Western world order” as being under threat—with “Norway” as an implicit part of this social entity also being under threat. That elicits the expressed need to stand together with “traditional allies” and fight for international law, human rights, and democracy worldwide, from the Middle East to Russia. On the Norwegian list of institutions for bolstering the “West” in this struggle we find not only the EU, the CoE, and the OSCE, but also NATO.43 In a sense, official Norway expands the liberal interventionist agenda in this period.

With a new government in power from September 2013 and before the crises in Ukraine, official Norwegian discourse on the Russian Other shifts further. Together with a continued emphasis on collaboration and good-neighborly relations in a High North governed by international law and multilateral collaboration, representations of Russia as a partner feature less prominently,44 whereas Russia as a human rights violator becomes more prominent. The Norwegian side argues that Russia’s new NGO law will obstruct people-to-people cooperation in the North. In the first direct meetings with Russian officials after the new Oslo government takes office, the rights of sexual minorities in Russia are brought up.45 The emphasis on Russia as a human rights violator is also evident in meetings between Norwegian officials and independent Russian NGOs during official visits to Russia.46

While this greater emphasis on Russia as human rights violator is voiced mostly by the Norwegian MFA and the Prime Minister, also MoD representations construct Russia as an opposite to Norway/the West/NATO in terms of values. Further, MoD texts now represent Russia as a security-oriented big power in the North. Modernization of the Russian military is no longer associated with “normalization” as in 2012, but with Russia’s rising big-power ambitions. Norway is held to need new military capabilities in the North to defend its sovereignty and protect its interests. Presenting a strong NATO as prerequisite for Norwegian security, the new government also seeks to strengthen transatlantic bonds and reinforce collaboration with NATO. These entities are represented as trustworthy, orderly, and reliable, whereas Russia’s status is tilting toward threatening. According to MoD texts, greater collaboration is needed within the transatlantic community, not necessarily with Russia. The NATO–Russia Council is seen as the best multilateral forum for relating to Russia. We also note the expressed ambition of giving Norway a more central role in NATO and of taking the NATO footprint North, through more allied training and exercises as well as military capabilities.47 In sum, and building on the changes in Norwegian Self/Other representations, we find a clear re-orientation toward a realist mode of policy already before the annexation of Crimea—in MoD understandings of the High North as primarily a security space, as well as in policies aimed at making national security a priority in the North.

4.2. A tectonic shift, 2014–2016

These new representations of “Russia,” “Norway,” and relations in the High North become amplified following the crises in Ukraine, which official Norwegian discourse describes as a tectonic shift in international relations, heading nearly every official account of international developments in 2014, 2015 and 2016. According to Minister of Foreign Affairs Børge Brende, Russia had “moved into a fundamentally new phase in relation to the outside world,” pursuing “power-politics belonging to a different age” and “acting in a way nobody had done since the Second World War.”48 In sum, the Russian Other becomes a rule-breaker, a thief, even a liar, an actor that disregards established institutions and cannot be trusted.49 “The High North,” and even “the Arctic,” are reframed in Norwegian government discourse with reference to Russia’s actions in Ukraine (later also to its actions in Georgia in 2008 and in Syria from 2015). The discursive positioning of the High North into the new orbit of potential conflict with Russia grows stronger and stronger, at least in MoD texts.50 In late 2016, the Minister of Defense states, with clear reference to Russia, “we cannot preclude that military force will not be used against Norway… It is no longer so that war is declared through diplomatic messengers.”51

The Arctic is still seen as a space governed by collaboration and international law, but Russia is, with reference to its actions in Ukraine, projected as a potential rule-breaker. Hence, Norway as a principled actor must hold Russia accountable.52 The government continues to speak of preserving cooperation, but the North now figures increasingly as a military strategic space. Security becomes a key priority for Norwegian foreign policy, with special reference to the North: With the new challenge from the eastern neighbor, the Norwegian Self figures as a small power in need of protection. Good-neighborly relations in the North are now construed as the result of Norway being firm, predictable, principled, and adhering to international law. By upping the civilian and military presence in the North and anchoring Norwegian security more firmly in NATO, Norway can contribute to “stability” and “predictability” in the North.53 It is even indicated that increasing such transatlantic presence and making Norway into “NATO in the North” may be required to keep tension levels low and preserve the Arctic as a “peaceful region.”54

As in all securitization processes, calls for unity and protection follow such re-phrasing of the Other from partner to threat.55 The Norwegian government’s discourse now projects the need to strengthen NATO collaboration and cooperation with the USA (implicitly or explicitly given as the guarantor of Norwegian security) and Europe. These three entities are represented as being trustworthy and having “good values.” Noteworthy is how “the West,” “NATO,” “the USA,” “Europe,” “the EU,” “the Nordic countries,” and “Norway” as “friends,” “allies” or “likeminded” get merged into one positive social unit/Self—juxtaposed to a Russian Other with no positive distinctions. The strength of the transatlantic vector in Norwegian foreign policy is now explicitly given as the precondition for good relations with Russia in the North—it is no longer an issue of what Russia and Norway can do together.56

Could the crises in Russian–Western relations be limited to the specific situation in Ukraine? Judging from the texts reviewed here, the Norwegian government’s answer was no.57 Relations had changed irrevocably: not even a solution to the Ukraine crises could alter the new security situation in Europe. The reason was Russia’s use of force against another European country, but also its poor democratic and human rights credentials. In breaking international law, Russia was undermining the international order and its entire underlying set of values. Russia is now represented as a power inclined to use military means instead of diplomacy, incapable of respecting other states’ political goals. “We” had been naïve, failing to understand Russia’s true intentions and ambitions. Russia had not become like “us” in terms of values. It was “assertive” and “aggressive,” and its military was now highly capable of “rapid,” “precise” operations that also Norway had to be prepared for. The modernization of Russia’s Northern Fleet is explicitly included in this narrative. The phrase Russia “has both the capacity and will to use military power for political gain” recurs, and by 2016 also the idea of Russia acquiring a “strategic advantage” in the North. Norway is no longer capable of “area denial.” Although Russia is never directly named as a “threat” to Norway in official discourse, taken together, the various representations constitute Russia as a threat in the North. The proper response is no longer “strategic partnership” and “constructive engagement” but “firmness” and “deterrence”—and “reassurance” not of Russia, but of the Baltic states and Poland. “We” must realize that the deterioration in Russian–Western relations might spill over into the North. Standing by our allies and speaking out on negative developments in Russia becomes essential.58

Both MoD and MFA texts put the blame for deteriorating relations firmly and solely on the Russian side. Russia must “change its ways” first, before any improvement can take place. Here the MoD texts represent Russia as a threat to military security, and MFA texts more as a threat to international law—Norway’s “first-line defense.”59 The “liberal interventionist” position, which accords fundamental importance to the political system of a foreign state in defining how to relate to that state and the kind of policies to be pursued toward it, also becomes stronger in MFA discourse in this period.60

This new interpretation of Russia and relations with Russia in the North indicates that Norwegian polices on Russia have changed substantially since 2014, making it reasonable to label the mode of Norwegian policies on Russia as primarily realist. Norway immediately and unconditionally joined the EU sanctions regime on Russia in 2014. The policy initiatives taken in recent years, made acceptable by the changes in official representations of the Russian Other, have largely abandoned the Cold War practice of “balancing” between deterrence and reassurance: since 2017, 330 US Marines have been stationed at Værnes/Trondheim in mid-Norway, initially on a rotational basis but now apparently de facto permanently.61 The Norwegian MoD has also been lobbying for the establishment of a new maritime command in the North and has proposed a Norwegian contribution to the European missile shield, with reference to the “Russian threat.”62 This has been accompanied by a significant decline in diplomatic contacts. Between 2014 and mid-2016 not one Norwegian minister visited Russia. In June 2016, the Minister of Fisheries went to St Petersburg. Not until March 2017 did the Norwegian Minister of Foreign Affairs travel to Russia, to attend the conference “Arctic—Territory of Dialogue” in Arkhangelsk. Norwegian ministers would go to Kiev, London or various NATO capitals instead, to discuss greater collaboration, often in the military-strategic sphere and in the High North.63

4.3. Return of dialogue and conditional collaboration?

Historical discourses and representations have staying power, however. It took less than half a year following the annexation of Crimea before the Russian Other was again referred to as a “constructive” and “reliable partner in the North” and policies of “dialogue” were prescribed to balance the policies of deterrence—but these words were not often repeated, the two first (“constructive” and “reliable”) occurring only once in the reviewed texts.64 “Dialogue” appears several times in MoD texts, but more as a reluctant caveat to the heavy and repeated accent on “deterrence.”65

In MFA texts, “dialogue” with Russia on Arctic issues reappears only well into 2016.66 The High North returns as the land of opportunity, at least for Norway and as regards energy, natural resources, and tourism.67 The “Arctic”/“High North” is now given as Norway’s key foreign policy interest-area, often represented as a “peaceful and stable region” with reference to “all the states” respecting the Law of the Seas.68 It is also acknowledged that the North is of strategic importance for Russia, even that Norway needs “to understand Russia’s interests and goals.”69 The idea of collaboration with Russia in the North on common interests gradually returns in MoD, MFA as well as Prime Minister texts. However, the emphasis is on cooperation when that is in Norway’s “interest;” asserting Norwegian sovereignty stands as a key aim in Norwegian policies.70

There is emphasis on upholding Norwegian–Russian cooperation to the extent possible in the traditional spheres of fisheries, nuclear safety, environment and natural resource management, search and rescue in the Barents Sea, people-to-people collaboration, the Barents Council and Secretariat, and the Arctic Council, at least when addressing audiences in Northern Norway.71 This type of collaboration with Russia is construed as being in Norway’s national interest. However, it needs to be matched by increased military presence in the North at sea, as well as in stronger surveillance capabilities.72

In the texts studied here, the Oslo government did not securitize the stream of refugees entering Norway from Russia over Storskog in Finnmark county in the fall of 2015 as part of the “Russian threat” or as “hybrid warfare,” although that image featured strongly in the wider public debate.73 The swift solution was framed in official discourse as part of the traditional good-neighborly relations and extensive experience of collaboration between Norway and Russia.74

By late 2016, the term “reassurance” (with reference to Russia, not to NATO allies) re-appears in official strategic vocabulary as a necessary complement to “deterrence.”75 However, it now seems more of a claim employed to create rhetorical continuity between current Norwegian policies and the policies of “balancing” during the Cold War. Moreover, the emerging official talk about “reassurance” came in response to criticism of Norwegian government policies voiced in the domestic debate.76

Nevertheless, Norwegian policies came to reflect this mix of realist and institutionalist understandings. While funding for the Barents Secretariat and cultural collaboration in the North increased, and cooperation in the fields of “people-to-people,” search and rescue, coast and border guards, nuclear safety, etc. continued,77 the policy implementation of “dialogue” in Norwegian initiatives and activities seems to amount to supporting “dialogue” in the NATO–Russia Council.78 That reflects the low weight accorded to such policies in official statements.

In this period, Norwegian official discourse on “Russia,” “Norway,” and “the West” (in all its incarnations)—and on the relations between these social entities—in the High North shifts toward a juxtaposition of threat/protection, bad/good, etc. Realist and security-oriented policies become logical, and collaborative policies in line with an institutionalist mode less so.

5. How Russia views Norway and the Arctic

Not surprisingly, Norway occupies a lesser place in the Russian official discourse than the other way around. Due to the paucity of documents focusing on Norway, here we examine the Russian discourse explicitly on Norway and on interaction in the Arctic more broadly.

5.1. Russia on the Arctic 2012–2016: harmony threatened by NATO?

In general, in official Russian discourse in 2012–2016 we note an emphasis on the Arctic as an area of opportunity for Russia—and as a region characterized by successful international cooperation. The Arctic is an example for other, less peaceful regions.79 Also after 2014, the picture is of continuing Arctic cooperation despite the overall worsening of international relations.80 Russia maintains the need to avoid militarization of the Arctic, stressing that there are no military solutions to the challenges facing the Arctic.

In Moscow’s view, the clearest threat to the current state of affairs in the Arctic region is a military approach of Western countries—especially attempts to get NATO involved in the Arctic. Back in 2012, Lavrov warned:

[In the Arctic], the situation is not that complicated when it comes to military blocs, which are not there, although some of our partners are persistently trying to call for NATO to come there. We oppose this. We believe that such a step will be a very bad signal to militarize the Arctic, even if it is the case that NATO simply wants to come there and get comfortable. Militarization of the Arctic should be avoided by all possible means.81

While we have seen above that Norway presents the stability and peacefulness of the Arctic region as well as good-neighborly relations with Russia as depending on NATO engagement in the region, Russia holds a diametrically opposed view.82 And while Norway consistently presents its positions as a logical answer to Russia’s changing behavior, Russia likewise presents its actions as reactive, and is irritated at what it sees as hypocritical expectations:83

Patrolling of remote areas with strategic airplanes used to be carried out by two parties only: the Soviet Union and the United States—that was back in Cold War times. In the early 1990s, we, the new, modern Russia, stopped these flights, while our American friends just continued to fly along our borders. For what? Some years ago we also resumed these flights. And you want to say that we behaved aggressively? (…) American submarines are on permanent duty by the Norwegian coasts, and their missiles can reach Moscow in 17 minutes. While we removed our bases from Cuba a long time ago, even those with no strategic significance. And you want to say that we behave aggressively? (…) Everything we do is simply a response to threats emerging against us. Moreover, we do this in a perfectly limited volume and scale, but sufficient to guarantee Russia’s security. Or did someone expect us to disarm unilaterally?84

Russia itself does not hide its markedly increased military attention toward the Arctic, as indicated in Figure 2 above. In the Western press, Russian activity is often framed as part of an offensive strategy, and evidence of Russian militarization of the Arctic.85 In the official Russian discourse, however, these efforts do not constitute militarization: they are represented as purely defensive, aimed largely at addressing domestic concerns (e.g., environmental protection); rather than constituting a threat, they are framed as being about establishing good governance domestically in the Russian Arctic.86

Some, like Rosneft CEO Igor Sechin, stress that the “competition for resources in the Arctic is getting tougher,” between Arctic and non-Arctic actors.87 Yet, in general, the emphasis remains on Russian efforts in the Arctic as being natural and necessary in order for Russia to be a responsible Arctic actor, managing resources, upholding sovereignty and being prepared for any threats that may arise. The expansion of military infrastructure and activity is represented as “restrained and reasonable in scale (…) simply in keeping with what Russia unquestionably needs to do to ensure its defense capability,”88 and as necessary after decades of neglect, not least in light of increased interest and better access to the Northern Sea Route and the Northern shores.89 As Putin stated in August 2014:

This is our territory, and we will restore all this military infrastructure and the infrastructure of the Ministry of Emergency Situations, in parts also because we need to ensure the safe passing of convoys and trade routes, and not in order to fight or confront anyone. (…) Many perceive our activity with concern, and are frightened by this activity. We have already said many times that we will act exclusively in accordance with international law. That is how we always have acted and how we will act in the future. [In the Arctic] many other states have their interests. We will take these interests into account and work to achieve acceptable compromises—and at the same time of course assert our own interests.90

In many ways, Russian efforts in the Arctic are represented as a return to the normal—a representation maintained also by the Norwegian side early in the period under study: Russia wants to utilize its proud Arctic history in today’s changing natural and political setting.

5.2. Norway seen from Moscow: increasingly “NATO in the North”?

Russian officials elaborate on relations with Norway especially in the context of ministerial visits, but also in commenting on specific events and answering questions from the press. In this explicit, official Russian discourse on Norway, we find several distinct representations of Norway, fairly stable, but with a shift in emphasis since 2014: Norway is increasingly seen as the prolonged arm of NATO and the USA—a significant point, given the representation of NATO as a threat.

Initially, Norway appears mainly as a good neighbor, in bilateral relations and through multilateral institutions like the Arctic Council, the Northern Dimension, and the Barents Euro-Arctic Council.91 Norway is often mentioned in the energy context, with Statoil as a promising corporate partner for Russian companies and an example of a successful state corporation. Norway gets recognition for its contribution to cooperative efforts aimed at removing chemical weapons from Syria. In particular, the 2010 maritime delimitation agreement between Russia and Norway is hailed as a key achievement under the Medvedev presidency,92 and is later defended against internal Russian accusations that the treaty was a “gift” from Russia to Norway—the treaty is presented as “just and in accordance with international law,” and “advantageous to both states.”93

Prior to Norwegian Minister of Foreign Affairs Brende’s visit to Moscow in January 2014, his Russian counterpart Lavrov had a clear and positive message:

The relations between Russia and Norway are developing dynamically and with good results within all the important directions. The dialogue at the level of the states’ leadership is deepening: last year there were two meetings between the prime ministers—April 5 in St Petersburg and June 4 in Kirkenes. The perspectives for organizing new contacts are being discussed.94

During the visit itself, Lavrov dismissed insinuations from the press that rising Russian–Western tensions had negative impacts on Russian–Norwegian relations.95 However, he would soon start answering such questions differently.

Representations of Norway as a “good neighbor” are increasingly complemented by representations of Norway as a country that consciously chooses to be a less good neighbor. Catering to its Western partners, Norway is seen as acting against both Russia’s and Norway’s own interests.

In October 2014, Lavrov visited the border town of Kirkenes on the occasion of the 70th anniversary of the Soviet liberation of Northern Norway in World War II. Amid praise of the veterans, Norway’s honoring of the wartime history, and the shared “joint combat brotherhood” that “substantially strengthened the fundament for good-neighborliness and friendly relations,” Lavrov also commented on the current state of affairs in bilateral relations:

Today these relations are of course experiencing a certain tension in connection with Norway’s joining of the unilateral restrictive measures against Russia for reasons, as we understand it, lie outside of the country. (…) We hope that common sense and each country’s national interests—and not external pressure—in the end will prevail.96

Lavrov notes how Russia’s and Norway’s joint interests are threatened by “various directions of the bilateral cooperation being subject to artificial restrictions, based on Euro-Atlantic solidarity and with reference to the Ukrainian crisis.”97 Here Norway is presented as part of a Euro-Atlantic social entity seen as hostile toward Russia.

This identification has also framed events on Svalbard. In Russian–Norwegian relations, disagreements on the Norwegian management of Svalbard have a long history. In the period under study, one episode is particularly instructive—one that also taps into the discontent expressed by Lavrov.

On April 18, 2015, Russian Deputy Prime Minister Dmitrii Rogozin paid a brief visit to Svalbard as his plane made a layover before he headed further north into the Arctic. In 2014 Rogozin had been added to the EU/Norwegian sanctions list and banned from entering Norway. The Norwegian authorities reacted negatively to what they saw as a Russian provocation and breach of Norwegian sovereignty. In turn, their Russian counterparts accused Norway of not respecting the Svalbard Treaty of 1920, which allows access to Svalbard for all citizens of the signatory states,98 and regretted this “unfriendly step” from the Norwegian side.99 The Russian MFA saw this not as an isolated incident, and expressed doubt over Norwegian willingness to continue “the spirit of partnership in the Arctic that Norway until now always has shown.” In the same statement, it acknowledged problems in the bilateral relationship: “We regret Norway’s initiative to join the EU’s anti-Russian sanctions, which will have negative consequences for Russian–Norwegian relations and, we believe, leads to our Norwegian neighbors having a distorted perception of reality.”100 Again, Norway’s acting in concert with its Western partners is presented as harming good-neighborly relations.

One distinct and important representation of Norway could be seen as the logical extreme of Russian concerns about Norway’s Russia policy being dictated by its allies. This representation places Norway as part of the US military system, and that system as an offensive force directed against Russia. Addressing the Seliger Youth Camp in August 2014, Putin stated:

The Arctic plays a very important role for us when it comes to safeguarding our security, because—unfortunately—it is the case that US attack submarines are concentrated there, not far from the Norwegian coast, and I remind you that the missiles they carry would reach Moscow within 15–16 minutes.101

It is in this narrative that Norway’s decision to invite 330 US Marines to be based near Trondheim on a “rotational” basis is placed. As explained by the Russian MFA spokesperson Mariya Zakharova:

Obviously, we have taken note of this fact. We believe that it contradicts the Norwegian policy of not allowing foreign military bases in the country in peacetime. (…) This decision by the Norwegian government appears to be yet another link in a chain of US-led military preparations that have markedly intensified lately against the backdrop of the anti-Russian hysteria. This step clearly does not contribute to maintaining stability and security in the North of Europe.102

Also in other fields of the bilateral relationship, Norway is represented as essentially obeying orders from Washington, as when the Russian MFA criticized Norway for extraditing a Russian citizen to the USA at the request of the US Secret Services, arguably at the expense of respect for international law—a “politicized” approach that Russia would “take into account in the further development of relations with Norway.”103

Russian representations of Norway change during the period under study, effectively merging Norway into NATO/the USA, a social entity long construed as the threatening Other. Representations of Russia that appear through the texts also evolve, although more in degree than as a qualitative change: the representations of Russia as a responsible international actor promoting predictable relations between equal partners stand out even more clearly as Norway is increasingly presented as working against these ideals to the benefit of NATO.

In line with the changing Russian representations of the Arctic and the key actors in this region, we observe changes in Russian military policies. Examples include the establishment of the Joint Strategic Command North in 2014 and the creation in early 2015 of the 80th Arctic Brigade, both ahead of schedule.104 We also note the increase in Russian snap military drills in the Arctic and in naval and air patrols near Norwegian territory, as well as enhanced submarine training in Arctic waters.105 All these changes are presented as responses to NATO activity in the North. Overall, it is reasonable to label the mode of Russian policies in the Arctic as increasingly realist.

In sum, then, Russia’s developing mode in relation to Norway in the Arctic 2012–2016 shows an unmistakable drift—from an institutionalist mode based on the perception that both states benefit from pursuing their own interests in a predictable manner, to a more realist mode. Seen from Moscow, this drift is due to policy changes on the Norwegian side—in particular, Norway’s acting in concert with its Western partners.106 As a result, security concerns may seem to crowd out other aspirations in relation to Norway.

6. Conclusions

We began by asking whether the strained and conflict-prone relations between Russia and the West following the crisis in Ukraine have metastasized to the Arctic, shaping and changing interaction between two previously close partners in the North, Norway and Russia. Our answer is yes. Despite the cautious return of the discourse on dialogue and good-neighborly relations on the Norwegian side, and Russia’s insistence that it wants relations in the Arctic to develop along a peaceful, cooperative trajectory, these countries’ representations of each other since 2014 have paved the way for realist mode policies on both sides, moving them into a more conflictual, security-oriented relationship.

The parallel trajectories are as follows: On the Norwegian side, representations of the Arctic as the land of opportunity and collaboration and Russia as a trustworthy partner conditioned the continuation of the institutionalist mode of policies up to mid-2013. There was a parallel push to increase strategic capabilities and NATO attention to the North, but not legitimized with reference to Russia as a “threat.” Belligerent representations of Russia in Norwegian official discourse first emerge with reference to Russia posing a threat to liberal and democratic values. These are then coupled with new projections of Russia’s military modernization in the Arctic as a possibly dangerous sign of rising big-power ambitions from the summer of 2013, that is, before the crises in Ukraine. Representations then shift dramatically, with Russia being constituted as a threat and Norway as a vulnerable entity in need of allies and protection.107 Crucially, Norwegian policies seem to have downgraded their Cold War aspect of “balancing.” Diplomatic contact and initiatives on the top political level as well as clear restrictions on foreign military bases and exercises in Norway—all policies that could reassure Russia that Norway would not be used as a US/NATO military launchpad against Russia—are scarce indeed. In the mix of modes on the Norwegian side, diplomatic management loses ground, given the new weight accorded to security concerns and the distribution of military power in the first years after 2014.

On the Russian side, representations of Norway as a good, predictable neighbor wishing to develop relations with Russia on an equal footing to the benefit of both states have been accompanied by representations of a different Norway. This Norway, presented as the result of deliberate Norwegian policy choices, acts as the representative of NATO and the USA in the region. Indeed: Norway is NATO in the region. In a Russian context where NATO and US military presence are seen as major threats to continued peaceful development in the Arctic region, this shift in representations is of great consequence. We can say that Russia’s previous inclination to pursue policies in an institutionalist mode has been tilting toward policies reflecting a realist mode, expressed not only through increasing military activity but also through the denial of entry to Russia—on grounds of national security—for several Norwegian journalists, businessmen and activists in the border region.108

How did these shifts come about? Above we have stressed the interaction effects involved in such shifting Norwegian and Russian representations and approaches in the Arctic. The starting point for both states was that, despite the overall worsening of Russian–Western relations, the Arctic should be protected as a space for peaceful interaction. If we take the wording of official statements at face value, the deterioration has been driven by the interpretation of what the other party is, does, and wants to achieve in the Arctic. Both parties then legitimize their own shift to a more one-sidedly realist mode of policy with reference to moves made by the other side. While Moscow indirectly identifies Norway as part of “US militarization” and highlights NATO’s increasing attempts to get involved in the Arctic already in 2012, Oslo re-emphasizes Russia as a threat to liberal values from late 2012 onward, and, in its continuing efforts to bring NATO to the North, implicitly as a potential security threat. Given these brewing suspicions on both sides before 2014 it is not surprising that a negative pattern of interaction should ensue. From this, we can outline three broad points about how interaction works and how the fault lines over Ukraine have been exported to the Arctic.

First, the policies pursued by one state are affected by the actions of the other party. As seen from Norway, Moscow’s actions in Ukraine played into representations of Russia as a potential threat, making the establishment of a stronger NATO footprint in the North appear a logical policy priority. In turn, such moves on the Norwegian side played into Russia’s already clearly articulated fears of such a footprint, spurring Moscow to step up what are presented as defensive military activities in the Arctic. Pointing out this negative spiral effect is almost banal from an analytical perspective, but it is politically controversial in the current public debate on Russia in Norway, as it is frequently mistaken as an attempt to apportion guilt among the parties. Our point here is to highlight that how Western states relate to Russia matters, and vice versa. With the current official representations of each other as potential threats in the Arctic, moves to strengthen one side’s defense will appear offensive from the other side, pushing the spiral upward, and drawing attention to security issues at the expense of other issue areas.

Second, when two parties view and represent each other as hostile and threatening in one theatre (say, Ukraine), this representation will not be isolated from how they view each other and relate to each other in other theatres (say, the Arctic). Reviewing the changing pattern of Norwegian official discourse as a whole, we find that Russian actions in Ukraine are given as a fundamental historical turning-point. Nearly every speech is introduced with reference to these actions—and such framing cannot fail to affect how Norway views Russia in the North. Representations of Russia as an actor in Ukraine were quickly echoed in representations of Russia as an actor in the Arctic. There has been a massive interaction effect from Russian actions in Ukraine to Norwegian framings and policies on Russia in the North. Here the parallel on the Russian side is how Norway’s rapid and unconditional accession to the Western sanctions regime affected Russia’s framing of Norway in the North. There is also a very practical link between theatres. The rapid movement of Russia’s armed forces in Ukraine immediately affected Norwegian military planning, as Norway decided it was essential to be capable of rapid response in the North.109

Third, when two parties increasingly view each other as threatening, new and sometimes unrelated events may get framed as springing from the general hostility of the other, as part of the same chain of hostile actions. Initially, Norway stated that Russia was not a direct threat; it also noted that there was no increase in Russian military activity in the North. But then a connection was made between heightened Russian military activity in the Baltic Sea and Russian military modernization in the Arctic—and the latter no longer looked like “normalization.”110 Similarly, in the Russian view, sanctions, large-scale military exercises in the North, and US Marines at Værnes are all interlinked. The exact size of the forces at Værnes is less important here—these events are seen as connected to a hostile US agenda directed against Russia, and include militarizing the Arctic.

Of course, politics in the Arctic are not driven solely by these two countries, or only by the top political leadership. Also within official Russian–Norwegian relations we have found potential for a return to views of Self and Other that could make policies of collaboration, or at least tighter diplomatic contact, logical and reasonable once again. However, with the (re)turn to the Russian image of Norway as NATO in the North, and the Norwegian image of Russia as a power willing and able to use force, the Arctic appears less likely as a collaborative space for the coming years. Tellingly, Norway’s announcement on June 12, 2018 that it would increase the number of US marines in Norway from 330 to 700, stationing half of them further north in Indre Troms, was followed the next day by the Russian announcement of yet another snap military exercise involving 36 Russian warships close to the Norwegian border—with both Norway and Russia likely to interpret their counterpart’s actions as further confirming the necessity of their own change of policy modes.111

NOTES

- 1. Robert Legvold, “Managing the New Cold War: What Moscow and Washington Can Learn from the Last One,” Foreign Affairs, July/August (2014): 74–84.

- 2. Geir Hønneland and Leif Christian Jensen, “Norway’s Approach to the Arctic: Politics and Discourse,” in Handbook of the Politics of the Arctic, eds. Lars C. Jensen and Geir Hønneland (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, 2015), 462–481.

- 3. Elana Wilson Rowe and Helge Blakkisrud “A New Kind of Arctic Power? Russia’s Policy Discourses and Diplomatic Practices in the Circumpolar North,” Geopolitics, 19 (1) (2014): 66–85.

- 4. In order to reflect the language use in the texts under study, the article uses the terms “the Arctic” and “the High North” interchangeably.

- 5. David Campbell, Writing Security (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1992).

- 6. Patrick T. Jackson and Daniel H. Nexon, “Relations before States: Substance, Process and the Study of World Politics,” European Journal of International Relations, 5 (3) (1999): 291–332; Patrick T. Jackson, Civilizing the Enemy: German Reconstruction and the Invention of the West (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2006).

- 7. Charlotte Epstein, The Power of Words in International Relations: Birth of an Anti-whaling Discourse (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2010), 341.

- 8. Anne L. Clunan, The Social Construction of Russia’s Resurgence (Washington, DC: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2009); Viatcheslav Morozov, “Subaltern Empire?” Problems of Post-Communism, 60 (6) (2013): 16–28; Andrei Tsygankov, Russia’s Foreign Policy: Change and Continuity in National Identity (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2013).

- 9. Halvard Leira, “‘Our Entire People are Natural Born Friends of Peace’: the Norwegian Foreign Policy of Peace,” Swiss Political Science Review, 19 (3) (2013): 338–356.

- 10. Lene Hansen, Security as Practice (New York: Routledge, 2006); Julie Wilhelmsen, Russia’s Securitization of Chechnya: How War Became Acceptable (New York: Routledge, 2017).

- 11. To limit the number of documents on the Norwegian side, we in addition excluded documents where Russia(n) was mentioned only once. We have used the regular expressions “\bRussland|\brussisk|\brusser” together with “\barktis|nordområde” on the Norwegian side, and “норве[жг],” “крайн.{2,3} север,” “\bаркти[чк]” on the Russian side. All searches are case-insensitive. While these terms do not correspond directly in the two languages (“крайний север” is, for example, used mainly about Russia’s domestic Arctic, while “nordområdene,” translated as the High North in English, refers to both the North of Norway and the North as an international meeting place), we believe that our search terms cover the empirical issues in focus here.

- 12. The search expressions are as described in the previous footnote.

- 13. Here, in order to avoid mentions of “Norwegian” as in, e.g., “the Norwegian Sea,” we modified the regular expression used to search for “Norway”/”Norwegian” to “норвег|норвеж[ец]|норвежск(ий|ой|ая|ого|им|ое|ими|ие)(?!( мор(?!як)|(,| и) (баренцев|карск|балтийск|черн|северн|средиземн|гренланд|красн)))”.

- 14. Most MFA mentions of Norway in 2014 were made in connection with Minister of Foreign Affairs Børge Brende’s visit to Moscow in January, and Minister of Foreign Affairs Sergei Lavrov’s Kirkenes visit in October. Moreover, nearly half of the mentions of the Arctic in Presidential Administration transcripts in 2014 stem from a single meeting on Arctic development.

- 15. Jennifer Milliken, “The Study of Discourse in International Relations: A Critique of Research and Methods,” European Journal of International Relations, 5 (2) (1999): 225–254; Kevin C. Dunn and Iver B. Neumann, Undertaking Discourse Analysis for Social Research (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2016).

- 16. For the most comprehensive and recent account of Norwegian–Russian relations in the twentieth century, see Sven G. Holtsmark (ed.), Naboer i frykt og forventning: Norge og Russland 1917–2014 (Oslo: Pax, 2015).

- 17. Katarzyna Zysk, “Mellom fredsretorikk og militær opprustning: Russlands sikkerhetspolitiske og militære atferd i nordområdene,” in Norge og Russland: sikkerhetspolitiske utfordringer i nordområdene, eds Tormod Heier and Anders Kjølberg (Oslo: Universitetsforlag, 2015), 71.

- 18. Olav Riste, Norway’s Foreign Relations (Oslo: Universitetsforlaget, 2001), 214–217; Hallvard Tjelmeland and Gunnar Thorenfeldt, “Ny kald krig, nye fiendebilder,” in Holtsmark, Naboer i frykt og forventning, 493–524.

- 19. Anne-Kristin Jørgensen and Geir Hønneland, “In cod we trust: Konjunkturer i det norsk-russiske fiskerisamarbeidet,” Nordisk Østforum, 27 (4) (2013): 353–376.

- 20. Olav Schram Stokke and Geir Hønneland (eds), International Cooperation and Arctic Governance: Regime Effectiveness and Northern Region Building (New York: Routledge, 2007); Geir Hønneland and Leif C. Jensen, “Norway’s Approach to the Arctic: Politics and Discourse,” in Handbook of the Politics of the Arctic, eds. Lars C. Jensen and Geir Hønneland (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, 2015), 462–481; Vladislav Goldin, “Barentssamarbeidet,” in Holtsmark, Naboer i frykt og forventning, 615–627.

- 21. Tormod Heier, Influence and Marginalisation: Norway’s Adaptation to US Transformation Efforts in NATO, 1998–2004 (Oslo: Dept. of Political Science, University of Oslo, 2006); Anders Kjølberg, “Norsk sikkerhetspolitikk og nordområdene,” in Norge og Russland: Sikkerhetspolitiske utfordringer i nordområdene, eds. Tormod Heier and Anders Kjølberg (Oslo: Universitetsforlaget, 2015), 35–36.

- 22. Geir Hønneland and Anne-Kristin Jørgensen, “Kompromisskulturen i Barentshavet,” in Norge og Russland: Sikkerhetspolitiske utfordringer i nordområdene, eds Tormod Heier and Anders Kjølberg (Oslo: Universitetsforlaget, 2015), 64.

- 23. Zysk, “Mellom fredsretorikk og militær opprustning,” 71.

- 24. Geir Hønneland, Russia and the Arctic: Environment, Identity and Foreign Policy (London: Tauris, 2016), 44.

- 25. Jørgen Holten Jørgensen, Russisk svalbardpolitikk: Svalbard sett fra den andre siden (Trondheim: Tapir Akademisk Forlag, 2010).

- 26. Hønneland and Jensen, “Norway’s Approach to the Arctic,” 14; Leif C. Jensen, “Seduced and Surrounded by Security: a Post-structuralist Take on Norwegian High North Securitizing Discourses,” Cooperation and Conflict, 48 (1) (2012): 80–99.

- 27. Elana Wilson Rowe, “Arctic Hierarchies? Norway, Status and the High North,” Polar Record, 50 (1) (2013): 72–79.

- 28. Øystein Jensen, “Delelinjen i Barentshavet, Svalbard,” in Holtsmark, Naboer i frykt og forventning, 565–575.

- 29. Jensen, “Seduced and Surrounded by Security.”

- 30. Marie Haraldstad, “Embetsverkets rolle i utformingen av norsk sikkerhetspolitikk: Nærområdeinitiativet,” Internasjonal Politikk, 72 (4) (2014): 431–451; Paal Hilde and Helene Widerberg, “Norway and NATO: The Art of Balancing,” in Common or Divided Security? German and Norwegian Perspectives on Euro-Atlantic Security, eds. Robin Allers, Carlo Masala and Rolf Tamnes (Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang, 2014), 199–218.

- 31. Hønneland, Russia and the Arctic, 94–98.

- 32. Marlene Laruelle, “Resource, State Reassertion and International Recognition: Locating the Drivers of Russia’s Arctic Policy,” The Polar Journal, 4 (2) (2014): 253–270, at 259–260.

- 33. N2; N4; N5; N6; N9; N10; N12; N14; N18; N22; N23; N25 (here and in the following: see appendix for references to primary sources).

- 34. N11; N18.

- 35. N6; N9; N10; N24; N17.

- 36. N7; N6; N20.

- 37. N1; N26.

- 38. N1; N3; N8; N13; N15.

- 39. N11.

- 40. N18; N23.

- 41. N16.

- 42. N19; N20; N21; N24.

- 43. N24.

- 44. N27; N30.

- 45. N32; N31; N33.

- 46. N33.

- 47. N34; N28; N29.

- 48. N35.

- 49. N51; N62; N67; N68.

- 50. N51; N52; N53; N55; N57; N58; N59; N64; N70.

- 51. N73.

- 52. N53; N57; N61.

- 53. N57; N58; N64; N65; N69; N70.

- 54. N66; N71.

- 55. Wilhelmsen, Russia’s Securitization of Chechnya.

- 56. N35; N37; N39; N46; N49; N51; N52; N58; N63; N66; N69; N71; N73.

- 57. N37; N39; N40; N43; N44; N47; N48; N49; N51; N52; N54; N58; N60; N63; N64; N65; N68; N70; N71.

- 58. Ibid.

- 59. N38; N45; N48; N65; N67; N71.

- 60. N49; N63; N71.

- 61. Simen Tallaksen and Magnus Lysberg, “Har kommet for å bli,” Klassekampen, October 7, 2017. http://www.klassekampen.no/article/20171007/ARTICLE/171009964.

- 62. “Klassekampen: Forsvaret bruker Russland som argument for rakettskjold,” Klassekampen, May 15, 2017. http://www.klassekampen.no/article/20170515/NTBI/73052045.

- 63. N36.

- 64. N39; N41; N45.

- 65. N39; N41; N45.

- 66. N65; N66; N71.

- 67. N42; N45; N61.

- 68. N72; N71.

- 69. N70.

- 70. N53; N56; N57; N58; N67.

- 71. N45; N46; N53; N74.

- 72. N56; N63.

- 73. Lars Rowe, “Fornuft og følelser: Norge og Russland etter Krim,” Nordisk Østforum, 32 (2018): 1–20, at 11.

- 74. N58; N61; N63.

- 75. N71.

- 76. N70; N71.

- 77. N50; N58; N63.

- 78. N70.

- 79. E.g. R4.

- 80. R21; R19.

- 81. R2.

- 82. See also R9.

- 83. R16; R24.

- 84. R16. Here Putin also criticizes the US withdrawal from the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty and NATO expansion,

- 85. See, e.g., Andrew Osborn, “Putin’s Russia in Biggest Arctic Military Push since Soviet Fall,” Reuters, January 30, 2017. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-russia-arctic-insight/putins-russia-in-biggest-arctic-military-push-since-soviet-fall-idUSKBN15E0W0.

- 86. R8.

- 87. R8.

- 88. R14.

- 89. R20.

- 90. R10.

- 91. R17.

- 92. R1.

- 93. R3.

- 94. R6.

- 95. R7.

- 96. R12.

- 97. R13.

- 98. Rowe, “Fornuft og følelser.”

- 99. R18.

- 100. R15.

- 101. R10. For a pre-Crimea example, see R5.

- 102. R22.

- 103. R23.

- 104. See Valery Konyshev and Alexander Sergunin, “Is Russia a Revisionist Military Power in the Arctic?” Defense & Security Analysis, 30 (4) (2014): 323–335.

- 105. Pavel Devyatkin, “Russia’s Arctic Strategy: Military and Security (Part II),” The Arctic Institute, February 13, 2018. https://www.thearcticinstitute.org/russias-arctic-military-and-security-part-two/.

- 106. R11.

- 107. This shift in Norway’s approach to Russia is validated by the findings presented in Andrea Sofie Nilssen, Norges Russland-retorikk: fra brobygging til fiendebilder (Oslo: Forsvarets stabsskole, 2015).

- 108. Atle Staalesen, “Barents Observer Editor Thomas Nilsen Is Declared Unwanted in Russia by FSB,” The Barents Observer, March 9, 2017. https://thebarentsobserver.com/en/civil-society-and-media/2017/03/barents-observer-editor-thomas-nilsen-declared-unwanted-russia; Atle Staalesen, “Northern Fleet Conducted 4,700 Exercises This Year,” The Barents Observer, November 30, 2017. https://thebarentsobserver.com/en/security/2017/11/northern-fleet-conducted-4700-exercises-year.

- 109. N47; N64; N59.

- 110. N51; N58.

- 111. NRK Finnmark, “36 russiske krigsskip seiler nå ut i Barentshavet,” June 13, 2018. https://www.nrk.no/finnmark/36-russiske-krigsskip-seiler-na-ut-i-barentshavet-1.14083102.

Appendix: Primary sources

- N1. 10 January 2012. MoD. URL: https://www.regjeringen.no/id668600/.

- N2. 11 January 2012. MFA. URL: https://www.regjeringen.no/id668688/.

- N3. 11 January 2012. MoD. URL: https://www.regjeringen.no/id668652/.

- N4. 18 January 2012. MFA. URL: https://www.regjeringen.no/id670011/.

- N5. 8 February 2012. MFA. URL: https://www.regjeringen.no/id671987/.

- N6. 14 February 2012. MFA. URL: https://www.regjeringen.no/id672235/.

- N7. 5 March 2012. MFA. URL: https://www.regjeringen.no/id674151/.

- N8. 9 March 2012. MoD. URL: https://www.regjeringen.no/id674398/.

- N9. 19 March 2012. MFA. URL: https://www.regjeringen.no/id685010/.

- N10. 26 March 2012. MFA. URL: https://www.regjeringen.no/id676397/.

- N11. 30 March 2012. MoD. URL: https://www.regjeringen.no/id677527/.

- N12. 17 April 2012. MFA. URL: https://www.regjeringen.no/id678814/.

- N13. 31 May 2012. MFA. URL: https://www.regjeringen.no/id684092/.

- N14. 24 July 2012. MoD. URL: https://www.regjeringen.no/id696983/.

- N15. 22 August 2012. MoD. URL: https://www.regjeringen.no/id697872/.

- N16. 21 September 2012. MoD. URL: https://www.regjeringen.no/id699552/.

- N17. 24 October 2012. MoD. URL: https://www.regjeringen.no/id705685/.

- N18. 25 October 2012. MFA. URL: https://www.regjeringen.no/id706229/.

- N19. 15 November 2012. MFA. URL: https://www.regjeringen.no/id708173/.

- N20. 10 January 2013. MFA. URL: https://www.regjeringen.no/id715305/.

- N21. 10 January 2013. MFA. URL: https://www.regjeringen.no/id712061/.

- N22. 17 January 2013. MFA. URL: https://www.regjeringen.no/id712316/.

- N23. 20 January 2013. MFA. URL: https://www.regjeringen.no/id714439/.

- N24. 12 February 2013. MFA. URL: https://www.regjeringen.no/id714380/.

- N25. 21 February 2013. MFA. URL: https://www.regjeringen.no/id714818/.

- N26. 19 August 2013. MFA. URL: https://www.regjeringen.no/id733950/.

- N27. 28 October 2013. MFA. URL: https://www.regjeringen.no/id744676/.

- N28. 5 November 2013. MoD. URL: https://www.regjeringen.no/id745013/.

- N29. 15 November 2013. MoD. URL: https://www.regjeringen.no/id745704/.

- N30. 20 November 2013. Office of the PM. URL: https://www.regjeringen.no/id745992/.

- N31. 5 December 2013. Office of the PM. URL: https://www.regjeringen.no/id747451/.

- N32. 17 December 2013. MFA. URL: https://www.regjeringen.no/id748116/.

- N33. 4 February 2014. MFA. URL: https://www.regjeringen.no/id750451/.

- N34. 11 February 2014. MoD. URL: https://www.regjeringen.no/id750997/.

- N35. 25 March 2014. MFA. URL: https://www.regjeringen.no/id753809/.

- N36. 29 April 2014. MoD. URL: https://www.regjeringen.no/id758000/.

- N37. 20 August 2014. MoD. URL: https://www.regjeringen.no/id766031/.

- N38. 21 August 2014. MFA. URL: https://www.regjeringen.no/id766098/.

- N39. 3 September 2014. MoD. URL: https://www.regjeringen.no/id766769/.

- N40. 1 October 2014. MoD. URL: https://www.regjeringen.no/id2005205/.

- N41. 6 November 2014. MFA. URL: https://www.regjeringen.no/id2010099/.

- N42. 11 November 2014. Office of the PM. URL: https://www.regjeringen.no/id2340334/.

- N43. 9 December 2014. MFA. URL: https://www.regjeringen.no/id2356470/.

- N44. 13 January 2015. MoD. URL: https://www.regjeringen.no/id2359590/.

- N45. 4 February 2015. MFA. URL: https://www.regjeringen.no/id2394190/.

- N46. 5 February 2015. MFA. URL: https://www.regjeringen.no/id2394200/.

- N47. 9 February 2015. MoD. URL: https://www.regjeringen.no/id2395220/.

- N48. 2 March 2015. MFA. URL: https://www.regjeringen.no/id2397982/.

- N49. 5 March 2015. MFA. URL: https://www.regjeringen.no/id2398550/.

- N50. 27 March 2015. MFA. URL: https://www.regjeringen.no/id2404225/.

- N51. 17 April 2015. MoD. URL: https://www.regjeringen.no/id2406948/.

- N52. 21 April 2015. MoD. URL: https://www.regjeringen.no/id2407440/.

- N53. 28 April 2015. MFA. URL: https://www.regjeringen.no/id2411977/.

- N54. 3 June 2015. MoD. URL: https://www.regjeringen.no/id2414909/.

- N55. 10 September 2015. MoD. URL: https://www.regjeringen.no/id2439236/.

- N56. 7 October 2015. MFA. URL: https://www.regjeringen.no/id2456538/.

- N57. 3 November 2015. Office of the PM. URL: https://www.regjeringen.no/id2460164/.

- N58. 12 November 2015. MoD. URL: https://www.regjeringen.no/id2461181/.

- N59. 24 November 2015. MoD. URL: https://www.regjeringen.no/id2462965/.

- N60. 12 January 2016. MoD. URL: https://www.regjeringen.no/id2470039/.

- N61. 10 February 2016. MFA. URL: https://www.regjeringen.no/id2475116/.

- N62. 26 February 2016. MoD. URL: https://www.regjeringen.no/id2477187/.

- N63. 1 March 2016. MFA. URL: https://www.regjeringen.no/id2477557/.

- N64. 21 April 2016. MoD. URL: https://www.regjeringen.no/id2485212/.

- N65. 3 May 2016. MFA. URL: https://www.regjeringen.no/id2499155/.

- N66. 12 May 2016. MFA. URL: https://www.regjeringen.no/id2500664/.

- N67. 26 May 2016. MFA. URL: https://www.regjeringen.no/id2501744/.

- N68. 16 August 2016. MFA. URL: https://www.regjeringen.no/id2509207/.

- N69. 16 August 2016. MFA. URL: https://www.regjeringen.no/id2509079/.

- N70. 29 September 2016. MoD. URL: https://www.regjeringen.no/id2513100/.

- N71. 3 October 2016. MFA. URL: https://www.regjeringen.no/id2515935/.

- N72. 3 October 2016. Office of the PM. URL: https://www.regjeringen.no/id2513446/.

- N73. 10 October 2016. MoD. URL: https://www.regjeringen.no/id2515195/.

- N74. 8 November 2016. MFA. URL: https://www.regjeringen.no/id2519678/.

- R1. 4 April 2012. MFA. URL: http://www.mid.ru/press_service/minister_speeches/-/asset_publisher/7OvQR5KJWVmR/content/id/162158.

- R2. 8 November 2012. MFA. URL: http://www.mid.ru/press_service/minister_speeches/-/asset_publisher/7OvQR5KJWVmR/content/id/135610.

- R3. 6 March 2013. MFA. URL: http://www.mid.ru/kommentarii/-/asset_publisher/2MrVt3CzL5sw/content/id/119662.

- R4. 15 May 2013. MFA. URL: http://www.mid.ru/press_service/minister_speeches/-/asset_publisher/7OvQR5KJWVmR/content/id/110214.

- R5. 3 October 2013. Kremlin. URL: http://kremlin.ru/events/president/transcripts/copy/19356.

- R6. 18 January 2014. MFA. URL: http://www.mid.ru/press_service/spokesman/answers/-/asset_publisher/OyrhusXGz9Lz/content/id/80130.

- R7. 20 January 2014. MFA. URL: http://www.mid.ru/press_service/minister_speeches/-/asset_publisher/7OvQR5KJWVmR/content/id/80074.

- R8. 5 June 2014. Kremlin. URL: http://kremlin.ru/events/president/transcripts/copy/45856.

- R9. 27 August 2014. MFA. URL: http://www.mid.ru/press_service/minister_speeches/-/asset_publisher/7OvQR5KJWVmR/content/id/673069.

- R10. 29 August 2014. Kremlin. URL: http://kremlin.ru/events/president/transcripts/copy/46507.

- R11. 23 October 2014. MFA. URL: http://www.mid.ru/press_service/spokesman/answers/-/asset_publisher/OyrhusXGz9Lz/content/id/715822.

- R12. 25 October 2014. MFA. URL: http://www.mid.ru/press_service/minister_speeches/-/asset_publisher/7OvQR5KJWVmR/content/id/743014.

- R13. 25 October 2014. MFA. URL: http://www.mid.ru/press_service/minister_speeches/-/asset_publisher/7OvQR5KJWVmR/content/id/743078.

- R14. 19 December 2014. Kremlin. URL: http://kremlin.ru/events/president/transcripts/copy/47257.

- R15. 20 April 2015. MFA. URL: http://www.mid.ru/kommentarii/-/asset_publisher/2MrVt3CzL5sw/content/id/1189235.

- R16. 6 June 2015. Kremlin. URL: http://kremlin.ru/events/president/transcripts/copy/49629.

- R17. 29 June 2015. MFA. URL: http://www.mid.ru/kommentarii/-/asset_publisher/2MrVt3CzL5sw/content/id/1515240.

- R18. 10 August 2015. MFA. URL: http://www.mid.ru/kommentarii/-/asset_publisher/2MrVt3CzL5sw/content/id/1648216.

- R19. 25 January 2016. MFA. URL: http://www.mid.ru/press_service/minister_speeches/-/asset_publisher/7OvQR5KJWVmR/content/id/2030466.

- R20. 12 April 2016. MFA. URL: http://www.mid.ru/press_service/minister_speeches/-/asset_publisher/7OvQR5KJWVmR/content/id/2227965.

- R21. 19 September 2016. MFA. URL: http://www.mid.ru/press_service/deputy_ministers_speeches/-/asset_publisher/O3publba0Cjv/content/id/2450934.

- R22. 28 October 2016. MFA. URL: http://www.mid.ru/press_service/spokesman/answers/-/asset_publisher/OyrhusXGz9Lz/content/id/2508717.

- R23. 30 November 2016. MFA. URL: http://www.mid.ru/press_service/spokesman/briefings/-/asset_publisher/D2wHaWMCU6Od/content/id/2540954.

- R24. 22 December 2016. Kremlin. URL: http://kremlin.ru/events/president/transcripts/copy/53571.