1. Introduction

Climate change has become an essential threat to both nature and human lives. In terms of sea areas, global warming, increased acidification and irregular weather patterns, interacting with many other pre-existing environmental stressors, such as pollution and overharvest, have resulted in the loss of marine biodiversity and the increasing vulnerability and impoverishment of local communities, which are heavily dependent on these marine resources. In this light, Marine Protected Areas (MPAs), which are area-based management tools, constitute part of a “natural solution” to climate change.1 The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) has defined an MPA as a protected area located in marine and coastal areas with a “clearly defined geographical space, recognized, dedicated and managed, through legal or other effective means, to achieve the long-term conservation of nature with associated ecosystem services and cultural values”.2 MPAs can mitigate the adverse impacts of climate change by avoiding or reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions resulting from the destruction or degradation of ecosystems, and by sequestering GHG emissions from the atmosphere.3 In another direction, by reducing stressors that amplify climate impacts and sustaining ecosystem processes and functions to promote resilience, MPAs can help biological systems better adapt to the changing climate.4 The mitigation and adaptation functions of MPAs are not entirely separate from each other.5 Promoting the resilience of ecosystems within MPAs may not only mitigate GHG emissions but also enhance the adaptation capability of ecosystems.

Effective governance of MPAs plays a crucial role in enhancing the resilience of ecosystems.6 In general, governance can be defined as “the process of decision-making and the process by which decisions are implemented (or not implemented)” and divided into diverse levels, including corporate, national, regional and international, and used for various purposes such as environmental protection, peacebuilding and food security.7 The core characteristics of good governance include “participation, rule of law, responsiveness, consensus orientation, equity, effectiveness and efficiency, accountability and strategic vision”.8 When it comes to environmental governance, sovereign States and intergovernmental organizations composed of sovereign States have been at the centre of governance since the creation of an international environmental agenda in the early 1970s.9 Yet, the idea that States are merely one type of actor among many, and the shift towards greater involvement of non-State actors have emerged as a result of changing conceptions of the relationship between politics and the market, and State and non-State actors.10 This ideational shift, as commented by the European Environment Agency,

is widely assumed to have progressed through several stages, starting in the 1970s with the rise of neoliberal thinking in politics and economics, progressing in the 1980s with large-scale political reforms in the United States and the United Kingdom, and expanding worldwide in the 1990s with the adoption of liberalising policies by an ever growing number of developing countries.11

Consequently, the concept of governance has broadened to include a growing number of non-State actors operating at different levels outside the narrowly defined State-centric realm.12 This evolving concept of governance also applies to MPA governance. Accordingly, in the context of MPAs, the essence of governance is vested in actors “who hold authority and responsibility and can be held accountable for the key decisions for a given protected area according to legal, customary or otherwise”.13 A variety of stakeholders can be involved in the governance of MPAs, including government agencies, non-government organizations (NGOs), local communities including indigenous people, and for-profit enterprises.14

Article 192 of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) obliges States to protect and preserve the environment of all kinds of marine areas, including territorial seas, exclusive economic zones (EEZ), continental shelves and areas beyond national jurisdiction (ABNJ).15 The establishment of an MPA, as an area-based management tool, falls inside the scope of the measures outlined in Article 194(5) of UNCLOS that States can take to prevent, reduce and control pollution of the marine environment, comprising “those necessary to protect and preserve rare or fragile ecosystems as well as the habitat of depleted, threatened or endangered species and other forms of marine life”.16 Accordingly, the rights to establish and govern MPAs, especially those located within a State’s territorial sea or EEZ, are usually vested in that State.17 Hence, government agencies are usually indispensable in the governance of MPAs. In fact, in contrast to land protected areas, most of the existing MPAs are governed by government agencies instead of private stakeholders. As a result, research on private protected areas mainly revolves around terrestrial examples, and by contrast, private governance of MPAs has gained little attention in scholarly discussion.18

However, it is predicted that the number of privately governed MPAs is likely to expand owing to the global push to create more MPAs.19 In October 2010, the Conference of Parties (COP) to the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) set global protected area targets and extended the target deadline from 2012 to 2020, stating that:

By 2020, at least 17 per cent of terrestrial and inland water, and 10 per cent of coastal and marine areas, especially areas of particular importance for biodiversity and ecosystem services, are conserved through effectively and equitably managed, ecologically representative and well connected systems of protected areas and other effective area-based conservation measures, and integrated into the wider landscapes and seascapes.20

In a June 2017 press release, Cristiana Palmer, the Executive Secretary of the CBD, declared that “the world is on track to protect over 10% of the globe’s marine areas by 2020”.21 Despite the rapid expansion of MPAs, she reminded people that it is also essential to ensure that the established MPAs are governed effectively and fairly.22 Scholars have expressed concerns about the phenomenon of “paper parks”, in reference to legally established MPAs where current protection activities do not suffice to achieve conservation objectives.23

Climate change exacerbates the problem of “paper parks”. As climate change pressures continue to mount in the coming years, interest in and initiative to establish MPAs to conserve marine environment will also increase.24 Moreover, responding to climate change will compound the governance costs of MPAs. Consensus has emerged that financial shortfall represents a significant challenge that curtails the capability of MPAs to halt the degradation of ecosystems.25 A survey of 79 MPAs in 36 countries reveals a median funding gap of 15% between current income and the amount required to achieve a minimum of conservation objectives, while the increment needed to secure ideal funding is 74%.26 No significant geographical variation in funding shortfalls is found, which means that MPAs in developed countries are just as poorly funded as those in developing countries. To make the situation worse, previous studies indicate that the cost of meeting conservation objectives in protected areas affected by climate change may increase by over 50% and in some cases by more than 100% in the future.27 As a result, MPA financial sustainability is expected to become an acute problem in the context of climate change.28 Such financing shortfalls will, in turn, be translated into management constraints and become an obstacle to effective MPA governance.

Public sources, mainly government budgets and foreign aid, constitute the cornerstone of MPA funding at present.29 In addition to public sources, MPA funding can also come from private sources, which can be further divided into external funding inflows and self-generated revenues. External funding inflows include NGO grants and private or voluntary donations, while self-generated revenues consist of resource user fees, tourism charges and payments for ecosystem services.30 In most countries, public revenue is becoming increasingly more difficult to access.31 In this light, private sources may provide a good solution for tackling the financing shortfalls of MPAs.32 Integrating private governance into MPA governance can attract more private sources of funding.

More importantly, empirical research on the governance effectiveness of 20 MPAs in different countries around the world indicates that employing a diversity of inter-connected incentives can strengthen the resilience of MPA governance, irrespective of the approaches adopted, which may range from government-led, to co-management-led, to community-led approaches.33 It follows that the diversity of institutions involved in governance systems are the key to resilience.34 Hence, the participation of private stakeholders in the governance process can enhance the resilience of the governance system concerned.

In this context, this paper aims to investigate the role of private stakeholders, which consists of NGOs, for-profit enterprises and local communities, in enhancing the governance effectiveness of MPAs so as to increase their capacity to tackle the adverse impacts of climate change. For the purpose of this research, an NGO is defined as “a non-profit organization that operates independently of any government, typically one whose purpose is to address a social or political issue”.35 Admittedly, there can be a whole range of different types of NGOs, for example, “from the local grassroots organization, via the nationally based NGO with international connections, to interest groups”.36 “NGO” as used in this paper refers to all of these types of organizations provided that they are involved in the process of MPA governance. As to the structure, this paper first outlines an analytical framework for studying the role of private stakeholders. Applying this analytical framework, it then continues to separately examine the role of each category of private stakeholder by observing and reviewing selected examples of MPA governance in different countries around the world. The last part concludes the discussion by proposing several recommendations about how to incorporate private stakeholders into MPA governance in the context of climate change.

2. An Analytical Framework for Studying the Role of Private Stakeholders

This paper seeks to explore the role of each category of private stakeholder in adapting MPA governance to climate change. For this purpose, an analytical framework is proposed in this part, based on a review of related literature, mainly including case studies of MPA governance and discussions on the influence of private stakeholders in developing international environmental law.37 The details of this analytical framework are set out below.

The analytical framework proposed here is mainly inspired by the methodology applied by Elisabeth Corell and Michele Bestsill in their study on the influence of NGOs on international environmental negotiations.38 In their research, Corell and Bestill first point out that the current literature on the role of NGOs in global environmental politics suffers from the following three weaknesses:

First, there is a tendency to treat all studies related to NGOs in the environmental issue area as a single body of research. Second, there is a surprising lack of specification about what is meant by “influence” and how to identify NGO influence in any given arena. Third, most studies stop short of elaborating the causal mechanisms linking NGOs to international outcomes in the environmental issue area.39

To tackle these three weaknesses, Corell and Bestill propose a framework to gather and analyze evidence of the influence of NGOs in a systematic manner by: “specifying which political arena the analysis pertains to; explicitly defining ‘influence’ and specifying what types of evidence can help indicate influence; and exploring the causal mechanisms between NGO activity and influence.”40 These three aspects have analogical implications for this research. As mentioned earlier, the present study focuses on the role of private stakeholders in adapting MPA governance to climate change. Hence, it is necessary to: specify which political arena the analysis relates to; establish the “effectiveness” of MPA governance and specify how to evaluate the degree of “effectiveness”; and examine the causal mechanisms between the activities of each category of private stakeholder and the effectiveness of MPA governance.

At the outset, in terms of the political context, this analysis pertains to the process of adapting MPA governance to climate change. In this context, the practice of private stakeholders aims to enhance the effectiveness of MPA governance so as to better adapt the MPA to new challenges brought by the changing climate.

Secondly, Peter Jones et al defines “effectiveness” as “the degree to which the ecological management objectives of an MPA are being fulfilled, particularly with regard to biodiversity and sustainable resource use”.41 In their MPA case studies, they measure the effectiveness of each MPA governance system according to its resilience,42 which refers to the “the capacity of a system to experience disturbance and still maintain its ongoing functions and controls”.43 The present study draws on this definition and measurement of “effectiveness”, considering that the concept of resilience, which emphasizes the ability to absorb change and disturbance in an adaptive manner, matches the research purpose of this paper, which focuses on the role of private stakeholders in adapting MPA governance to new challenges posed by climate change.44 To this effect, the “resilience” of an MPA governance system in absorbing change and disturbance adaptatively is used as a proxy for measuring “effectiveness”. This research does not use direct calculations of the effects of mitigation or adaptation to climate change to evaluate “effectiveness”, as the calculations of such effects rely heavily on sufficient scientific data, which is either difficult to access or, with respect to the MPAs studied here, currently unavailable.

Thirdly, we investigate the logical relationship between private stakeholders’ participation in MPA governance and the effects of this participation. In this regard, the case study method is employed. By examining and analyzing the involvement of each category of private stakeholder in cases of MPA governance in various countries, the strengths and weaknesses of the practice of each stakeholder can be uncovered.

To sum up, this analytical framework makes possible a systematic assessment of the role of each stakeholder category in adapting MPA governance to climate change. On the basis of the evaluation, the concluding part proposes several recommendations for future practice.

3. The Perspective of NGOs

It is widely recognized that NGOs play an increasingly important role in fostering international responses to climate change.45 NGOs are registered at the national level and can be legally established as trust funds, foundations, associations or nonprofit companies according to specific domestic legislation.46 Due to their professional knowledge and political or social influence, the pivotal role of NGOs in environmental conservation manifests in a variety of ways:

they try to raise public awareness of environmental issues; they lobby state decision-makers hoping to affect domestic and foreign policies related to the environment; they coordinate boycotts in efforts to alter corporate practices harmful to nature; they participate in international environmental negotiations; and they help monitor and implement international agreements.47

When it comes to the conservation of the marine environment, NGOs have taken an active part in influencing discussions on and setting the agenda for the establishment of MPAs.48 Apart from this, NGOs are also motivated to adopt innovative approaches to achieve effective long-term governance. In this part, two examples, including the Chagos MPA and the Chumbe Island Coral Park, are studied in order to reveal the salient features and problems of NGO practice in the MPA governance process.

One notable example of relevance is the role of the Chagos Environment Network (CEN) in the establishment of the controversial Chagos MPA. The CEN, as an NGO, is a coalition that comprises Kew Gardens, London Zoo, the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds, the Royal Society and the Marine Conservation Society.49 The Chagos Archipelago, which is located in the middle of the Indian Ocean and comprises a number of coral atolls, was colonized by the United Kingdom (UK) before Mauritius became independent in 1968. In conjunction with the move towards Mauritius’s independence, the UK government signed an agreement with the government of Mauritius - the Lancaster House Undertakings - which separated the Chagos Archipelago from the remainder of the colony of Mauritius and retained it under British control for defense purposes.50 In 2009, the CEN worked with other NGOs, including the Pew Charitable Trusts,51 to launch a proposal for the establishment of a vast marine reserve in the Chagos Archipelago.52 This MPA proposal prompted the UK government to start bilateral talks with the government of Mauritius. During these talks, the Mauritius side reiterated its concerns about issues relating to resettlement, access to fisheries resources, potential benefits that Mauritius should derive from any oil exploitation activities in or near the Archipelago, and economic development of the islands in a manner which would not prejudice Mauritius’s future enjoyment of sovereignty.53

In 2010, with little progress in bilateral talks, the UK government initiated and held a public consultation on the subject of the Chagos MPA. Three options were presented to the public: (1) “a full no-take marine reserve for the whole of the territorial waters and Environmental Preservation and Protection Zone (EPPZ)/Fisheries Conservation and Management Zone (FCMZ)”;54 (2) “a no-take marine reserve for the whole of the territorial waters and EPPZ/FCMZ with exceptions for certain forms of pelagic fishery (e.g., tuna) in certain zones at certain times of the year”;55 and (3) “a no-take marine reserve for the vulnerable reef systems only”.56 Apparently, the first option set out the strictest limitations on human activities within the MPA, in the sense that it declared a full no-take zone that covered a vast marine area. The responses from the public showed significant majority support for the first option. Consequently, the British government adopted the first option and formally established the Chagos MPA on 1 April 2010. Notably, the CEN also endorsed the first option.57 However, in its response to the public consultation, the CEN did not mention the position of the Chagossian community or that of other regional stakeholders. Being aware of Mauritius and the Chagossian groups, the CEN was of the view that “it is not disadvantageous to have the islands and their marine areas protected in their entirety now, since arrangements could be modified if circumstances changed”.58

Despite its intention to preserve the marine environment, establishment of the Chagos MPA has been subject to criticism pertaining to the insufficient involvement of local communities in the consultation process. It has been criticized that little attention was paid to the rights and interests of local communities, including the right of Chagos Islanders to return to the Archipelago.59 Consequently, Mauritius initiated arbitration against the UK, claiming that the latter was not entitled to establish the Chagos MPA according to UNCLOS and other rules of international law.60 Though the arbitral tribunal considered that it lacked jurisdiction to address whether the UK had the right to establish this MPA,61 it decided that the manner in which the MPA was declared violated Articles 2(3), 56(2), and 194(4) of UNCLOS, stating that:

(1) that the United Kingdom’s undertaking to ensure that fishing rights in the Chagos Archipelago would remain available to Mauritius as far as practicable is legally binding insofar as it relates to the territorial sea; (2) that the United Kingdom’s undertaking to return the Chagos Archipelago to Mauritius when no longer needed for defence purposes is legally binding; and (3) that the United Kingdom’s undertaking to preserve the benefit of any minerals or oil discovered in or near the Chagos Archipelago for Mauritius is legally binding.62

Another criticism is that despite the vital role that the CEN played in establishing the MPA, the extent to which the CEN will continue to contribute to the long-term monitoring and enforcement of the MPA remains to be seen.63 This concern is not groundless. According to Elizabeth De Santo’s observations, well-financed efforts made by NGOs tend to focus on MPA establishment rather than on effective long-term governance owing to the fact that “it can be difficult to convince NGOs and their donors of the need to fund the ongoing management and monitoring of PPA [Private Protected Area] arrangements, and not just their acquisition and/or establishment”.64

Furthermore, apart from establishing MPAs, successful efforts to adopt innovative approaches to effective long-term governance have been made by some NGOs. An illustrative example is the Chumbe Island Coral Park (CHICOP), an MPA established in Zanzibar, Tanzania and the first in the world to be privately governed.65 In 1993, the Government of Zanzibar (GoZ) leased the land area on the island for a period of 33 years to Chumbe Island Coral Park Limited (CHICOP Limited), which is a nonprofit company established with a specific purpose to “develop a financially sustainable model of MPA management through revenue generated from ecotourism”.66 In 1994, the GoZ entrusted the management of the MPA through a management agreement to CHICOP Limited for a renewable ten year period.67 The CHICOP is a no-take area where only non-consumptive and non-exploitative activities are permissible.68 The governance effectiveness of this MPA has turned out to be at a very high level. In an empirical study conducted by Peter Jones et al in 2011 of MPA governance among 20 MPAs located in different countries around the world, CHICOP ranked first.69

Several measures or solutions have contributed to the success of the CHICOP. First of all, the governance of CHICOP involves a wide range of stakeholders. An advisory committee was set up in 1995, which consists of two representatives from CHICOP Limited, four from different departments of the GoZ, four from neighboring fishing villages and one from the research community.70 Though recommendations made by the advisory committee do not bind CHICOP Limited, the advisory committee meetings, which are held at least twice a year, provide a formal forum for diverse stakeholders to get informed about and to voice their opinions on issues relating to management plans and project progress. Besides, village meetings with local communities adjacent to the CHICOP began in 1991 and have continued thereafter.71

Secondly, potential adverse impacts on the livelihoods of local communities have been overcome by employing people from nearby communities to work in the park and offering local communities other income opportunities such as “a regular market for food, building materials and handicrafts, outsourcing road and boat transport and craftsmen services during maintenance”.72 It is noteworthy that the CHICOP’s operations are labor-intensive because of the particular eco-technologies chosen, thereby providing more job opportunities and promoting the sustainable economic development of local communities.

Thirdly, marketing the CHICOP as a prime ecotourism destination through innovative channels including winning international environmental awards, gaining recognition by the international conservation community, targeted marketing over the Internet and cooperating with travel agents and tour operators, results in an increase of the revenue generated from ecotourism. The revenue is reinvested in covering the management costs and supporting environmental education programs.73 Besides, CHICOP Limited saves management costs by recruiting volunteers for professional assistance.

Fourthly, by offering environmental education to government officials, local communities, employees in the park, school pupils, tourism operators, visitors and the general public, the CHICOP raises public awareness on the importance and vulnerability of the marine ecosystem, which, in turn, enhances public support of this MPA governance project.74

Fifthly, CHICOP Limited has prioritized baseline surveys, and monitoring and research programs, which has not only helped establish the conservation value of the area but also proven valuable in aiding the MPA management.75

Despite previous good practice, CHICOP still faces several challenges. Though the land lease and the management contract are renewable upon expiration, CHICOP Limited has no legal assurances about renewal and must renegotiate each renewal with the GoZ.76 Moreover, the Zanzibar Investment Promotion and Protection Act of 2004 offers limited protection against the expropriation of the MPA by the GoZ, stipulating that interests or rights of investors might be expropriated in the presence of fair and adequate compensation according to Article 17 of the Zanzibar Constitution, namely “for defence and security of the people, health requirement, town planning and any other development in the public interest”.77 To this effect, the risk remains that this MPA might be expropriated for purposes of economic development. Other challenges relate to the financial sustainability of the MPA governance. The GoZ has adopted policies to encourage ecotourism and non-commercial work such as tax exemptions and reduced land lease charges. However, these policies are rarely implemented, which has been a source of conflict between the GoZ and the management team of CHICOP for years.78 Last but not least, the most severe threat to CHICOP’s economic sustainability is its heavy dependence on revenue generated from ecotourism in an international market that is sensitive to political turmoil, natural disasters and other risks.79

The above observations reveal that while most NGOs focus on the establishment of MPAs, some innovative NGOs have made efforts to promote MPA governance efficiency in the long term. The primary advantage of governance dominated by NGOs is that they can provide transformative frameworks for integrating various stakeholders by creating channels for the flow of information, structures for decision-making and forums for discussion.80 In contrast with government-led governance, NGOs have to build up a cooperative relationship with other stakeholders in order to gain legitimacy and public support. In contrast with the competing services offered by for-profit enterprises, NGOs tend to be more trustworthy owing to legal constraints on the distribution of profits and their focus on environmental protection and conservation.81 Consequently, the involvement of NGOs can significantly enhance the effectiveness of governance by involving direct stakeholders, including government officials, local communities and tourism operators, into the governance process.

However, it has to be noted that NGOs alone provide no substantive guarantee that benefits will be widely distributed and that conservation goals will be pursued.82 As shown by the Chagos MPA case, insufficient involvement of local communities and inadequate attention paid to their rights and interests may pose a challenge to the legitimacy of MPA governance.83 The Chagos MPA is not an isolated case. In 2003, Honduras designated the Cayos Cochinos as an MPA and entrusted responsibility for conservation to the Honduras Coral Reef Fund (HCRF). In 2004, WWF assisted HCRF in developing a management plan that claimed to take into account the participation of the local community, namely the Garifuna people. Nevertheless, the Garifuna still felt victimized owing to significant restrictions imposed on their fishing activities and little community participation in the decision-making process.84

Meanwhile, conservation goals cannot be achieved without the support of government agencies. As discussed above, governance efficiency at CHICOP still faces challenges owing to insufficient laws and policies and failure to implement relevant laws and policies meant to favor NGOs on the part of the GoZ. Besides, the economic sustainability of NGO-led governance is highly sensitive to fluctuations in the international tourism market. One author has suggested that an international insurance scheme could be established to help MPAs, especially privately governed MPAs, to buffer severe income loss from visitor fluctuations.85

4. The Perspective of Local Communities

Community-Based Management (CBM) is a bottom-up approach with the aim of incorporating local communities into the decision-making process in MPA governance.86 With the trend of decentralized environmental governance owing to the failure of the traditional government-led governance, CBM has become more common in both developed and developing States, as well as in both land-based and seabased protected areas since the 1980s.87 Nevertheless, the success of CBM projects varies widely. A number of previous studies have explored factors that influence the outcome of the CBM approach. For instance, Lindsey Wood concludes that clear land tenure, strong local institutions and interdisciplinary cross-scale linkages are three critical determinants of the success of the CBM approach.88 A few scholars go further and question the significance of participatory democracy in the context of developing countries, because of the lack of transparency in the CBM approach, especially in the unequal distribution of economic profits, which usually serves to heighten tensions rather than achieve conservation goals.89 In this light, this part intends to investigate the strengths and weaknesses of the CBM approach in the context of MPA governance.

The Seaflower MPA in Colombia is an illustrative example of the CBM approach. This MPA, as the first and largest MPA in Colombia, is managed by CORALINA, a regional autonomous government agency with authority over the environment of the San Andres Archipelago. The Seaflower MPA, located on San Andres Island, has been legally divided into zones designated for: (1) artisanal fishing; (2) non-entry; (3) no-take; (4) special use (activities that are required to achieve MPA objectives, including ports, shipping lanes and cruise-ship anchorage); and (5) general use. CORALINA collaborates with local communities in MPA governance, including indigenous islanders known as raizales. Local communities have final decision-making power in the MPA design. The consensus reached between CORALINA and local communities was recorded in formal agreements and subsequently enacted in law.90

This MPA has gained strong support from local communities owing to a high degree of involvement and participation in the governance process by these same communities. However, the primary challenge facing Seaflower is the lack of financial resources and enforcement support.91 First of all, since Seaflower has a weak nexus with the national government, the MPA receives no direct government funding, which has curtailed its ability to achieve environmental conservation and sustainable development objectives.92 Secondly, given that Colombia and Nicaragua used to dispute the Seaflower MPA waters, Colombia withdrew its navy vessels from this area as part of its litigation strategy to avoid conflict escalation, which resulted in an increase of illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing undertaken by foreign fishing vessels in the region.93 Though the Seaflower MPA waters are no longer in dispute after the International Court of Justice (ICJ) delimited a maritime boundary between the two States in 2012, it remains to be seen whether Colombia will deploy a military presence in the region to enforce the environmental legislation protecting the MPA, as Colombia and Nicaragua still have maritime disputes in an area not far from the MPA.94

Moreover, a crisis occurred in 2010 when the national government leased two blocks located within the Seaflower MPA to oil companies for oil exploration followed by exploitation. In response, CORALINA submitted a Popular Action, which was “a legal instrument granted to Colombians that allows them to seek protection of collective rights and interests related to their homelands, environment, and other interests”, to halt oil exploration.95 Under public pressure, the president of Colombia finally announced that the national government would revoke the leases and not carry out any oil exploration and exploitation within this MPA.

Apart from this incident, the lack of support by the national government also causes other problems. The population density in San Andres Island has been increasing due to the absence of national support to help deal with migration and population control issues. These external issues, including a high and continuously increasing population density, have caused significant pressure on ecosystems and resources within the Seaflower MPA. As a result, despite the establishment of the MPA, results of scientific research and monitoring reveal that the condition of most marine natural resources has not improved or even become worse in some cases.96

The preceding analysis indicates that the involvement and participation of local communities can increase their commitment and confidence in the MPA concerned. However, lack of support by the national government poses a significant challenge to effective implementation of MPA governance owing to both insufficient technical and financial resources and the incapability of dealing with external issues such as migration and population control.

Furthermore, distinctive from other private stakeholders, a unique issue that governance dominated by local communities may face is resistance to conservation objectives for cultural reasons. The governance of the Wakatobi National Park (WNP) in Indonesia serves as an example for discussion. The Bajau people are heavily dependent on the marine environment of the MPA for food, fuel and building materials.97 The Bajau see themselves as outsiders in Indonesia due to social and economic marginalization. As one of the most impoverished populations in Indonesia, the Bajau have a fundamentally different perception of marine resources compared to the rest of Indonesian society. The Bajau perceive marine resources as existing for exploitation and usage rather than conservation.98 This perception reflects their “predominantly subsistence lifestyle and distinct cultural and spiritual views regarding fish stocks and their abundance”.99 Hence, the Bajau have shown little support for the conservation objectives of the MPA and prefer to maintain their unique identity by abstaining from participating in any official government initiative. Besides, it is difficult for this community to adapt to alternative livelihoods provided that fishing is central to almost all aspects of the Bajau culture and lifestyle.

With the continuance of these cultural stereotypes and resistance, it can be predicted that the Bajau’s participation in MPA governance will remain negligible, and poverty will continue to increase, inevitably undermining the effectiveness of governance at the WNP. Based on this, one author comments that injustice will persist provided that “these programs are based upon a predominantly protectionist notion of ‘conservation’ rooted in Western scientific thought”.100 This comment underlines the importance of taking into account the culture and economic livelihoods of local communities instead of merely implementing conservation objectives based on scientific evidence. Nevertheless, harmonizing or balancing cultural imperatives with conservation goals remains a problem that warrants further attention and investigation.101

5. The Perspective of For-Profit Enterprises

The establishment of MPAs reallocates the rights and obligations of various stakeholders, especially local communities. Considering that harvesting marine resources including fishing usually constitutes the primary livelihood of local communities, MPA governance needs to consider compensation or alternative livelihood options for local communities since the displacement of rights to access marine natural resources may cause short-term hardships to these communities.102 In addition to directly employing the people from local communities to work at the MPA, the most common solution that offers an alternative livelihood to local communities is tourism, in the form of diving, boating, wildlife viewing, historical and cultural tourism, eco-tourism and even recreational fishing. The tourism business usually comprises the participation of for-profit enterprises, including travel agents, accommodation providers, restaurants, tour services, transportation and tourism-related infrastructure providers, which, in general, are referred to as “tourism-related companies” hereinafter. Notably, while it is uncommon in practice to have for-profit enterprises as de jure authorities to dominate MPA governance, they may act as de facto authorities that exert significant influence on MPA governance.

One notable example is the Sanya Coral Reef National Marine Nature Reserve (SCR-NMNR) in China. According to the 1994 Regulation on Nature Reserves, the SCR-NMNR is divided into three types of zones: core, buffer and experimental zones.103 Any extractive use of marine resources including fishing is prohibited within the whole SCR-NMNR. The core zones are no-entry areas, while in the buffer and experimental zones, non-extractive activities including ecotourism and education are allowed. Scholars describe the governance approach of the SCR-NMNR as “managed by the government with significant decentralization and/or influences from private organizations”, especially from tourism-related companies.104 The SCR-NMNR was designated by the State Council in 1990. However, in practice it was managed by the Sanya Municipal Government before 2002 following decentralization reforms across China. Management was taken over by the Hainan Provincial Government in 2002 due to an intensification in tourism. However, management remained heavily dependent on local resources, especially the tourism industry, owing to a lack of funding from both the central and provincial governments. Tourism development started in the SCR-NMNR in 1997. At present, twelve tourism-related companies are operating therein. Notably, tourism activities, including “diving and snorkeling, anchoring, sedimentation and tourism-related infrastructure development”, have caused damage to reef habitats and pose a significant and inadequately addressed challenge in MPA governance.105 Regulating these tourism activities has been difficult owing to resistance from local vested interests, which is understandable considering that tourism in this MPA has made significant contributions to the development of the local economy in the city of Sanya.

The situation seemed to improve when China enacted the Law on the Administration of the Use of Sea Areas in 2001.106 This law sets out regulations on the allocation of “sea user rights” in the internal waters and territorial seas of China. This law provides that ownership over these marine areas belongs to the State. Moreover, following this law, any individual or entity shall apply for “sea user rights” from the government if they want to enjoy exclusive use of certain marine areas for a period longer than three months. The law also stipulates that the competent authorities for approving such applications are the central and provincial governments. Lower-level governments, including municipal and county governments, are not entitled to grant “sea user rights”. In particular, projects involving the use of a sea area more than a certain size or major national construction projects shall be subject to the central government’s approval, while the power to approve other projects remains with the respective provincial governments.107 In 2006, a circular on “Further Strengthening the Administration of Sea Use Management within Marine Protected Areas” was issued by the State Oceanic Administration (SOA), which sets forth that “sea user rights” within a national marine nature reserve such as the SCR-NMNR shall be approved by the SOA.108

The 2001 law and the 2006 circular bring clarity to the authorization of “sea user rights” for tourism and other non-extractive activities within the SCR-NMNR, which used to be an area of competition among distinct levels of government. As a result, the rights enjoyed by tourism companies obtain explicit legal protection. This development may, in turn, motivate tourism companies to invest in the protection of coral reef habitats so as to benefit the long-term development of the tourism industry. Moreover, the introduction of “sea user rights” and the approval procedures may, to some extent, help achieve a better balance of power between pro-conservation higher-level government agencies and pro-development local governments.109 Yet, in practice, it is reported that some applicants and provincial governments agree to split bigger projects into several smaller projects in order to avoid the involvement of the central government.110

Another point worth addressing pertains to conflicts between tourism-related companies and local communities. Admittedly, the tourism industry not only provides a number of job opportunities for people from the local communities within the SCR-NMNR, but also invests in improving public infrastructure such as roads and schools in villages there. Besides, tourism-related companies offer additional financial and human resources to the governance of the SCR-NMNR by funding the employment of field wardens who are in charge of patrolling and enforcing MPA governance. However, the rapid development of the tourism industry has caused a loss of community access to coastal resources. Local governments, notably respective provincial governments, may be inept at representing the interests of the local communities, especially in a country where local officials are usually not directly elected by local citizens. By contrast, for-profit companies tend to have more bargaining power than local communities during negotiations with local governments, considering that the most important indicator for assessing and evaluating the political performance in China is economic development. In these circumstances, tourism-related companies have occupied well-developed coral reef areas, which have subsequently become inaccessible to local fishers. Even though tourism activities in these areas may lead to economic benefits, it is questionable whether local communities will be able to enjoy a proportionate share of these benefits.

Several lessons can be learned from the experience of MPA governance at the SCR-NMNR. At the outset, before the introduction of a transparent legal regime on the allocation of “sea user rights”, governance at the SCR-NMNR was dominated by the local government and for-profit enterprises. This collaboration enabled, to some extent, the SCR-NMNR to tackle specific conflicts by offering alternative livelihoods to local communities as a means of halting extractive activities.

However, this governance approach is not devoid of problems. In the face of intense economic driving forces, tourism activities have resulted in damage to reef habitats and thus become a significant governance challenge. Nevertheless, the legal clarity on “sea user rights” introduced by legislation may partly address this challenge. After obtaining explicit legal protection, for-profit companies may be motivated to invest in the protection of coral reef habitats so as to benefit from the long-term development of the tourism industry.

Moreover, the local communities have limited participation in the governance process. They are at a disadvantage when competing with for-profit companies for access to marine natural resources. In order to improve the participation and involvement of local communities, some scholars suggest that efforts need to be made to protect “the legitimate rights of traditional resources users, including the recognition of these rights and the empowerment of the holders in decision-making processes, and the equitable sharing of benefits from development and conservation”.111

Finally, it can be seen that the governance of this MPA excludes the involvement of NGOs. In fact, NGOs play an essential role in balancing between the governance objectives of development and conservation, because NGOs are devoted to and competent in protecting and conserving the marine environment, which may offset the influence exerted by pro-development local governments and for-profit enterprises.

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

The above observations and analysis show that all categories of private stakeholders, including NGOs, local communities and for-profit entities, can play a significant role in enhancing the effectiveness of MPA governance. NGOs are good at obtaining external funding to support governance systems. They are devoted to conservation objectives and are willing to adopt and experiment with innovative approaches during the governance process. They may also enjoy tax benefits and government subsidies. More importantly, NGOs are capable of providing transformative frameworks to integrate different stakeholders, including government agencies, local communities and for-profit entities, into governance systems. Nevertheless, under some circumstances, NGOs may have more interest in establishing MPAs than managing them for the long-term, and are prone to focus more on conservation objectives than the sustainable livelihood of local communities. Also, the sustainability of NGO governance may face uncertainty as a result of ambiguous government policies. In addition, governance systems that are dependent on tourism revenues are sensitive to fluctuations in international markets.

From another perspective, governance involving a high level of participation from local communities usually gains strong support from these communities. Public support for the CBM approach can strengthen the capability of a governance system to counteract the influence of government agencies that pursue policies counter to MPA governance objectives. However, owing to its weak nexus with government agencies, especially those at higher levels, governance led by local communities can be subject to a lack of technical and financial support, and be incapable of dealing with external issues such as immigration and population control. These weaknesses can significantly curtail an MPA’s capability to halt environmental degradation. Cultural values shared by local communities may also act as an obstacle to achieving conservation objectives.

Turning to for-profit enterprises, the involvement of these enterprises can contribute to governance effectiveness by providing alternative livelihoods for local communities and sustainable financial support for MPA governance systems. However, for-profit enterprises may focus more on economic development than conservation objectives, and compete with local communities for access to coastal resources.

The strengths and weaknesses of the practices of each category of private stakeholder in the MPA governance process are summarized in Table 1:

| Strengths | Weaknesses | |

| NGOs |

– Obtain sufficient external funding; – Provide transformative frameworks to integrate different stakeholders; – Enjoy tax benefits and subsidies; – Adopt innovative approaches to govern MPAs. |

– May focus more on MPA establishment than the MPA governance; – May focus more on conservation objectives than the sustainable livelihood of local communities; – Are subject to uncertainty caused by ambiguous government policies; – Are sensitive to fluctuations in international markets. |

| Local Communities |

– Gain strong support from local communities; – Prone to obtain broad public support for MPA governance. |

– Lack of technical and financial support; – Incapable of dealing with external issues such as immigration and population control; – Resistance to conservation objectives for cultural reasons. |

| For-Profit Enterprises |

– Provide alternative livelihoods for local communities; – Provide sustainable financial support for MPA governance. |

– May focus more on economic development than conservation objectives; – Compete with local communities for access to coastal resources. |

Furthermore, the preceding examples of MPA governance indicate that the desire for economic development usually accompanies conservation objectives. Indeed, these two types of interests can be harmonized in the long-term. The conservation of ecological systems within the MPA can pave the way for the sustainable economic growth generated from tourism and responsible use of marine natural resources. However, in the short term, local communities, for-profit enterprises and government agencies, especially those at lower levels, are prone to place a priority on the pursuit of economic development, sometimes at the cost of ecosystems. In contrast, NGOs are more devoted to conservation objectives owing to their specific purpose and legal constraints on the distribution of NGO profits. To this effect, incorporating NGOs into MPA governance can serve to advocate for and safeguard the conservation objectives of MPA governance as well as offset the influence exerted by other pro-development stakeholders.

Another point worth noting is that government agencies also play an essential role in influencing the effectiveness of MPA governance even in those governance systems dominated by private stakeholders. Firstly, there are specific external issues such as immigration and population control that can only be solved by government agencies, especially those at higher levels. Secondly, government agencies can significantly enhance the effectiveness of an MPA governance system by providing it with explicit and unambiguous protections in laws or policies. Thirdly, government agencies can implement tax benefits and subsidies to encourage NGO participation in local MPAs. Last but not least, since ownership of most marine areas is legally vested in a State, government agencies have the ultimate power to determine marine spatial planning and establish of MPAs. The effectiveness of MPA governance may also be affected by the existence of other MPAs in neighboring areas. Thus, private stakeholders may have to rely on government agencies to coordinate inter-MPA relations.112

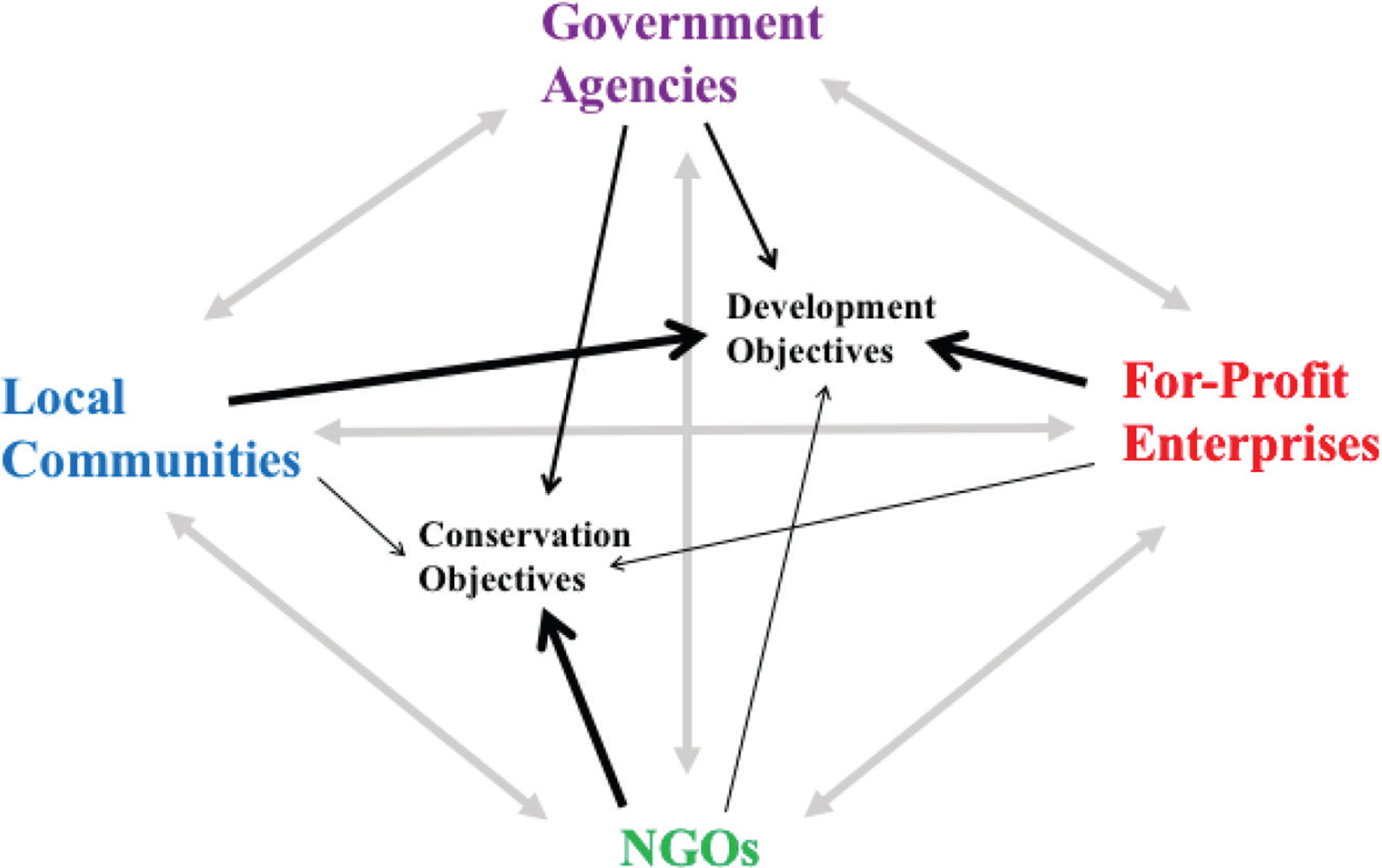

The above analysis, in fact, echoes the empirical research on 20 MPAs mentioned in the first part, which concludes that diversity in the institutions/stakeholders involved in governance systems are essential to enhance the resilience of MPA governance systems.113 The analysis in this paper is in line with this conclusion in the sense that: the functions of private shareholders can complement each other by maintaining a balance between conservation and development objectives, and meanwhile, government agencies and private shareholders can also collaborate with each other to achieve the effective governance of MPAs. Consequently, the ideal web of interconnections between stakeholders and governance objectives can be depicted as in Figure 1:

Notes: The author made this figure based on the analysis above, and inspired by Note. [33]. Thick lines exhibit strong interconnections while thin lines represent weak interconnections. The symbol ↔ indicates a two-way interaction between two stakeholders. The symbol → indicates a one-way interaction with a category of stakeholder, reinforcing a governance objective.

Several recommendations can be proposed to reinforce the interconnections between different stakeholders so as to enhance the resilience of MPA governance. Firstly, in general, it is essential to incorporate a variety of stakeholders into the governance process. As analyzed above, different stakeholders have different strengths and weaknesses, which can complement each other and make it easier to tackle various challenges such as climate change in a flexible and resilient manner. Secondly, it is recommended that government agencies enact laws or policies that endow private stakeholders with explicit and unambiguous rights and obligations. This kind of legal protection, which brings security and predictability, not only promotes a balance of power between private stakeholders and governmental agencies, but also ensures that private stakeholders can develop governance plans from a long-term and sustainable perspective. Thirdly, attention needs to be paid to the involvement of NGOs in the MPA governance process, because NGOs contribute to advocating and safeguarding conservation objectives and offset the influence exerted by other pro-development stakeholders. Moreover, government agencies are advised to encourage the establishment and development of locally-based NGOs, which can act as “brokers” connecting local communities and larger NGOs.114 Fourthly, the economic interests, involvement and cultural values of local communities should be taken into careful consideration in MPA governance since the livelihoods and lifestyles of local communities are usually profoundly affected by the establishment and governance of an MPA. Fifthly, while the involvement of for-profit enterprises can provide alternative livelihoods for local communities and sustainable financial support for governance systems, it is important to keep in mind that measures need to be taken to counterbalance pro-development objectives and to tackle the fierce competition between these enterprises and local communities for access to coastal resources.

To conclude this analysis, it should be noted that this paper does not claim to provide an exhaustive account of all privately governed MPAs that exist around the world. The selection of illustrative examples presented here is inevitably subject to the author’s own specialized areas of interest, but it aims to provide some insight into the practice of private stakeholders in MPA governance. With the number of privately governed MPAs expected to increase in the future, this paper serves as a starting point and contributes to the literature on the private governance of MPAs in the context of climate change.

NOTES

- 1. John E. Gross et al., Adapting to Climate Change (Gland : IUCN, 2016), 6.

- 2. Nigel Dudley, Guidelines for Applying Protected Area Management Categories Including IUCN WCPA Best Practice Guidance on Recognising Protected Areas and Assigning Management Categories and Governance Types (Gland : IUCN, 2008).

- 3. Gross et al., Adapting to Climate Change, 5.

- 4. Ibid., 6.

- 5. Ibid.

- 6. See Grazia Borrini-Feyerabend et al., Governance of Protected Areas: From Understanding to Action, Best Practice Protected Area Guidelines Series No. 20 (Gland, Switzerland: IUCN, 2013), 11.

- 7. United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (UNESCAP), What is Good Governance? https://www.unescap.org/resources/what-good-governance (accessed 3 October 2018).

- 8. Mihaela Kardos, “The Reflection of Good Governance in Sustainable Development Strategies,” Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 58 (2012): 1167.

- 9. European Environment Agency, Global Governance - the Rise of Non-State Actors: A Background Report for the SOER 2010 Assessment of Global Megatrends, Technical Report No. 4 (2011), 4.

- 10. Ibid., 13.

- 11. Ibid.

- 12. Ibid., 4, 13. Also see Kal Raustiala and Natalie Bridgeman, “Nonstate Actors in the Global Climate Regime,” UCLA School of Law Research Paper No. 07–29, https://ssrn.com/abstract=1028603 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1028603 (accessed 3 October 2018).

- 13. Borrini-Feyerabend et al., Governance of Protected Areas: From Understanding to Action, 11.

- 14. In the context of MPAs, actors socially endowed with legal or customary rights concerning water or natural resources are called “rightsholders”, which usually include government agencies and local communities. “Stakeholders” have a broader scope than “rightsholders”. Stakeholders refer to actors who possess direct or indirect interests and concerns about water or natural resources but do not necessarily enjoy a legally or socially recognized entitlement to them. See ibid., 15.

- 15. United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, adopted 10 December 1982, entered into force 16 November 1994, 1833 UNTS 396: Article 192.

- 16. Ibid., Article 194(5).

- 17. For MPAs that are founded in high seas, they are established by international agreements between or among interested States.

- 18. Most research on the private governance of protected areas has focused primarily on terrestrial examples. See Jeffrey A. Langholz and Wolf Krug, “New Forms of Biodiversity Governance: Non-State Actors and the Private Protected Area Action Plan,” Journal of International Wildlife Law and Policy 7.1–2 (2004).

- 19. Elizabeth De Santo, “From Paper Parks to Private Conservation: The Role of NGOs in Adapting Marine Protected Area Strategies to Climate Change,” Journal of International Wildlife Law & Policy 15.1 (2012): 25.

- 20. COP of CBD, Decision X/: Strategic Plan 2011–2020, Target 11, https://www.cbd.int/sp/targets/ (accessed 3 October 2018).

- 21. Global marine protected area target of 10% to be achieved by 2020, https://www.cbd.int/doc/press/2017/pr-2017-06-05-mpa-pub-en.pdf (accessed 3 October 2018).

- 22. Ibid.

- 23. See Enrico Di Minin and Tuuli Toivonen, “Global Protected Area Expansion: Creating More Than Paper Parks,” BioScience 65. 7 (2015): 638. Also see De Santo, “From Paper Parks to Private Conservation: The Role of NGOs in Adapting Marine Protected Area Strategies to Climate Change,” 25.

- 24. Ibid., 31.

- 25. Lucy Emerton et al., Sustainable Financing of Protected Areas: A Global Review of Challenges and Options (IUCN, 2006), 13–14.

- 26. Pippa Gravestock, Callum M Roberts, and Alison Bailey, “The Income Requirements of Marine Protected Areas,” Ocean & Coastal Management 51.3 (2008): 277. P Gravestock, “Towards a Better Understanding of the Income Requirements of Marine Protected Areas,” MSc Environmental Management for Business by Research, Institute of Water and Environment, Cranfield University at Silsoe (2002).

- 27. Sandy Andelman et al., “Conservation Focus: Costs of Adapting Conservation to Climate Change. Introduction,” Conservation Biology: the Journal of the Society for Conservation Biology 26.3 (2012): 385.

- 28. MPA financial sustainability can be defined as “the ability to secure sufficient, stable and long-term financial resources, and to allocate them in a timely manner and in an appropriate form, to cover the full costs of” MPAs and to ensure that MPAs “are managed effectively and efficiently with respect to conservation and other objectives”. See Emerton et al., Sustainable Financing of Protected Areas: A Global Review of Challenges and Options, 15.

- 29. Ibid., 13.

- 30. Ibid., 27.

- 31. Ibid., 12–13.

- 32. There are indications that private donations and investment of protected areas have increased over recent decades. Such increase probably reflects “greater consumer awareness and pressure on companies to invest in the environment, the promotion of ethical and ‘green’ considerations in the business world, and increased opportunities to successfully market products and services through association with conservation”. See ibid., 31.

- 33. PJS Jones et al., “Governing Marine Protected Areas: Social–Ecological Resilience through Institutional Diversity,” Marine Policy 41 (2013): 5.

- 34. Ibid., 12.

- 35. “NGO”, Oxford Dictionary, https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/ngo (accessed 3 October 2018).

- 36. Michele Betsill and Elisabeth Corell, “NGO Influence in International Environmental Negotiations: A Framework for Analysis,” Global Environmental Politics 1.4 (2001), 66.

- 37. Selected literature includes: PJS Jone et al., Governing Marine Protected Areas: Getting the Balance Right (Citeseer, 2011); PJS Jones et al., “Governing Marine Protected Areas: Social–Ecological Resilience through Institutional Diversity”; Langholz and Krug, “New Forms of Biodiversity Governance: Non-State Actors and the Private Protected Area Action Plan”; Elisabeth Corell and Michele Betsill, “A Comparative Look at NGO Influence in International Environmental Negotiations: Desertification and Climate Change,” Global Environmental Politics 1.4 (2001).

- 38. See Corell and Betsill, “A Comparative Look at NGO Influence in International Environmental Negotiations: Desertification and Climate Change,” 87. Also see Betsill and Corell, “NGO Influence in International Environmental Negotiations: A Framework for Analysis,” 65–85.

- 39. Ibid., 65.

- 40. Corell and Betsill, “A Comparative Look at NGO Influence in International Environmental Negotiations: Desertification and Climate Change,” 87.

- 41. Jone et al., Governing Marine Protected Areas: Getting the Balance Right: vii.

- 42. See PJS Jones et al., “Introduction: An Empirical Framework for Deconstructing the Realities of Governing Marine Protected Areas,” Marine Policy 41 (2013): 3.

- 43. Crawford S. Holling and Lance H. Gunderson, “Resilience and adaptive cycles,” in: Panarchy: Understanding Transformations in Human and Natural Systems, 25–62 (2002), quoted in Jone, Qiu, and De Santo, Governing Marine Protected Areas: Getting the Balance Right: vii.

- 44. This definition of effectiveness is also in line with IUCN’s identification of the five principles of good governance of protected areas: the legitimacy and voice principle, the direction principle, the performance principle, the accountability principle and the fairness and rights principle. See Borrini-Feyerabend et al., Governance of Protected Areas: From Understanding to Action: 59–60.

- 45. See Michele Merrill Betsill and Elisabeth Corell, NGO Diplomacy: the Influence of Nongovernmental Organizations in International Environmental Negotiations (Mit Press, 2008), 1. Also see Lee P Breckenridge, “Nonprofit Environmental Organizations and the Restructuring of Institutions for Ecosystem Management,” Ecology LQ 25 (1998): 692–93.

- 46. See Melissa Moye and Barry Spergel, Financing Marine Conservation: A Menu of Options (WWF Center for Conservation Finance, 2004), 23–28.

- 47. Betsill and Corell, “NGO Influence in International Environmental Negotiations: A Framework for Analysis,” 67.

- 48. Noella J. Gray, “Sea Change: Exploring the International Effort to Promote Marine Protected Areas,” Conservation and Society 8.4 (2010): 331–338.

- 49. See Fred Pearce, “The Chagos Archipelago-Where Conservation Meets Colonialism,” https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2010/feb/18/chagos-nature-reserve-greenwash (accessed 3 October 2018).

- 50. See Chagos Marine Protected Area Arbitration (Mauritius v. United Kingdom), in Award of 18 March 2015 (PCA 2015), para. 77.

- 51. The Pew Charitable Trusts is a US charity, which launched the Global Ocean Legacy project in 2006 with the aim to establish the world’s first generation of large-scale MPAs. See The Pew Charitable Trusts, “Archived Project: Global Ocean Legacy,” http://www.pewtrusts.org/en/archived-projects/global-ocean-legacy (accessed 3 October 2018).

- 52. Sadie Gray, “Giant Marine Park Plan for Chagos: Islanders may return to be environmental wardens,” https://www.commondreams.org/news/2009/02/09/giant-marine-park-plan-chagos (accessed 3 October 2018).

- 53. See Chagos Marine Protected Area Arbitration (Mauritius v. United Kingdom), paras. 134, 44.

- 54. Rosemary Stevenson, “Whether to establish a marine protected area in the British Indian Ocean Territory: Consultation Report,” Annex UKCM-121 of Chagos Marine Protected Area Arbitration (Mauritius v. United Kingdom): para. 32.

- 55. Ibid., para. 38.

- 56. Ibid.

- 57. Ibid., para. 33.

- 58. Ibid., para. 37.

- 59. See Pearce, “The Chagos Archipelago-Where Conservation Meets Colonialism”.

- 60. Chagos Marine Protected Area Arbitration (Mauritius v. United Kingdom), in Award of 18 March 2015 (PCA 2015), paras. 6–7.

- 61. Ibid., para. 230.

- 62. Ibid., para. 547(B).

- 63. See De Santo, “From Paper Parks to Private Conservation: The Role of NGOs in Adapting Marine Protected Area Strategies to Climate Change,” 33.

- 64. Ibid.

- 65. Lina M Nordlund et al., “Chumbe Island Coral Park-Governance Analysis,” Marine Policy 41 (2013): 110.

- 66. Ibid.

- 67. Ibid., 111.

- 68. Ibid., 115.

- 69. See Jones, Qiu, and De Santo, “Governing Marine Protected Areas: Social–Ecological Resilience through Institutional Diversity,” 7.

- 70. Nordlund et al., “Chumbe Island Coral Park-Governance Analysis,” 115.

- 71. Sibylle Riedmiller, “Private Sector Investment in Marine Protected Areas-Experiences of the Chumbe Island Coral Park in Zanzibar/Tanzania,” (2003): 6.

- 72. Nordlund et al., “Chumbe Island Coral Park-Governance Analysis,” 114.

- 73. Ibid. Also see Riedmiller, “Private Sector Investment in Marine Protected Areas-Experiences of the Chumbe Island Coral Park in Zanzibar/Tanzania,” 4–5.

- 74. Nordlund et al., “Chumbe Island Coral Park-Governance Analysis,” 114–15.

- 75. Ibid., 115.

- 76. Ibid.

- 77. Zanzibar Investment Promotion and Protection, Act No. 11 of 2004, Article 22(1). The Constitution of Zanzibar, 2006, Article 17.

- 78. Nordlund et al., “Chumbe Island Coral Park-Governance Analysis,” 114.

- 79. Riedmiller, “Private Sector Investment in Marine Protected Areas-Experiences of the Chumbe Island Coral Park in Zanzibar/Tanzania,” 10–11.

- 80. Breckenridge, “Nonprofit Environmental Organizations and the Restructuring of Institutions for Ecosystem Management,” 704.

- 81. Ibid., 701.

- 82. Ibid., 705.

- 83. See Pearce, “The Chagos Archipelago-Where Conservation Meets Colonialism”.

- 84. Natalie Bown, Tim S. Gray, and Selina M Stead, Contested Forms of Governance in Marine Protected Areas: A Study of Co-Management and Adaptive Co-Management (Routledge, 2013). 59.

- 85. Riedmiller, “Private Sector Investment in Marine Protected Areas-Experiences of the Chumbe Island Coral Park in Zanzibar/Tanzania,” 10–11.

- 86. Derek Armitage, “Adaptive Capacity and Community-Based Natural Resource Management,” Environmental Management, 35.6 (2005): 703.

- 87. Wilhelm A Kiwango et al., “Decentralized Environmental Governance: A Reflection on Its Role in Shaping Wildlife Management Areas in Tanzania,” Tropical Conservation Science 8.4 (2015): 1081.

- 88. Lindsey Wood, “Community-Based Natural Resource Management: Case Studies from Community Forest Management Projects in Ghana, Mexico, and United States of America,” NRES 523—International Resource Management (2008): 27.

- 89. Marie-Christine Cormier-Salem, “Participatory Governance of Marine Protected Areas: A Political Challenge, An Ethical Imperative, Different Trajectories. Senegal Case Studies,” SAPI EN. S. Surveys and Perspectives Integrating Environment and Society, 7.2 (2014): 9.

- 90. Elizabeth Taylor et al., “Seaflower Marine Protected Area: Governance for Sustainable Development,” Marine Policy 41 (2013): 60.

- 91. Lincoln Bent, “Case study: Seaflower Marine Protected Area. Archipelago of San Andres, Old Providence & Santa Catalina. Colombian Caribbean.” (Master Thesis). https://courses.cit.cornell.edu/crp5540/EIS_case_stud.pdf.

- 92. Elizabeth Taylor et al., “Seaflower marine protected area: Governance for sustainable development,” 61.

- 93. Territorial and Maritime Dispute (Nicaragua v. Colombia), Judgment of 19 November 2012 (ICJ): 663, 672.

- 94. Question of the Delimitation of the Continental Shelf between Nicaragua and Colombia beyond 200 nautical miles from the Nicaraguan Coast (Nicaragua v. Colombia) (ICJ, pending).

- 95. Elizabeth Taylor et al., “Seaflower marine protected area: Governance for sustainable development,” 60.

- 96. Ibid., 61.

- 97. Julian Clifton, “Refocusing Conservation through a Cultural Lens: Improving Governance in the Wakatobi National Park, Indonesia,” Marine Policy 41 (2013): 80.

- 98. Ibid., 85.

- 99. Ibid.

- 100. Ibid.

- 101. For more discussions about the conflict between the cultural sentiment and the conservation objectives, see Caroline Good, Dawn Burnham, and David W Macdonald, “A Cultural Conscience for Conservation,” Animals 7.7 (2017).

- 102. Nathan James Bennett and Philip Dearden, “From Measuring Outcomes to Providing Inputs: Governance, Management, and Local Development for More Effective Marine Protected Areas,” Marine Policy 50 (2014): 97.

- 103. Regulations of the People’s Republic of China on Nature Reserves, Decree of the State Council of the People’s Republic of China No. 167, adopted 2 Sep 1994, entered into force 1 Dec 1994.

- 104. Wanfei Qiu, “The Sanya Coral Reef National Marine Nature Reserve, China: A Governance Analysis,” Marine Policy 41 (2013): 52.

- 105. Ibid., 51.

- 106. Law of the People’s Republic of China on the Administration of the Use of Sea Areas, Order No. 61 of the President of the People’s Republic of China, adopted 27 Oct 2001, entered into force 1 Jan 2002.

- 107. Ibid., Article 18.

- 108. Circular on “Further Strengthening the Administration of Sea Use Management within Marine Protected Areas, Guo Hai Fa [2006] No. 26, dated 22 Sep 2006.

- 109. Qiu, “The Sanya Coral Reef National Marine Nature Reserve, China: A Governance Analysis,” 52–53.

- 110. Xiaojun Wang, “Modification of the Law of the P.R.C. on Administration of the Use of Sea Areas,” (in Chinese) China Environmental Management 9.4 (2017): 80.

- 111. Qiu, “The Sanya Coral Reef National Marine Nature Reserve, China: A Governance Analysis,” 55.

- 112. For discussion on inter-MPA relations, see Nordlund et al., “Chumbe Island Coral Park-Governance Analysis,” 115–16.

- 113. Jones, Qiu, and De Santo, “Governing Marine Protected Areas: Social–Ecological Resilience through Institutional Diversity,” 12.

- 114. See Clifton, “Refocusing Conservation through a Cultural Lens: Improving Governance in the Wakatobi National Park, Indonesia,” 85.